полная версия

полная версияPicturesque Pala / The Story of the Mission Chapel of San Antonio de Padua Connected with Mission San Luis Rey

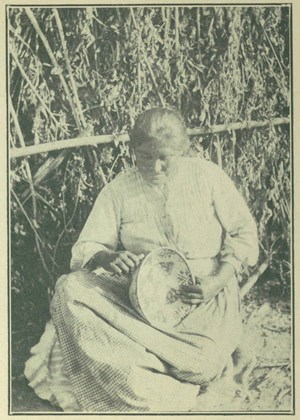

With her materials duly prepared the weaver is now ready to go to work. What drawing has she to represent the shape of her basket; what complicated plan of the design she intends to incorporate in it? How much thought has she given to these two important details? Where does she get them from? What art books does she consult? She cannot go down to the art or department store and purchase Design No. 48b, or 219f, and her religion, if she be a good woman (that is, good from the Indian, not the white man or Christian standpoint), will not allow her to copy either one of her own or another weaver's form or design. She, therefore, is left to the one resort of the true artist. She must create her work from Nature, out of her own observations and reflections. Thus patterning after Nature the shapes of her baskets are always perfect, always uncriticizable. There is nothing fantastic, wild, or crazy about them, as we often find in the original creations of the white race. They are patterned after the Master Artist's work, and therefore are beyond criticism.

But who can tell the hours of patient and careful observation, the thought, the reflection, put upon these shapes and designs. The busy little brain behind those dark-brown eyes; the creative imagination that sees, that vizualizes in the mind and can judge of its appearance when objectified, must be developed to a high degree to permit the use of such intricate, complicated and complex designs as are often found. There are no drawings made, no pencil and paper used, not even a sketch in the sand as some guessers would have the credulous believe. Everything is seen and worked out mentally, and with nothing but the mental image before her, the artist goes to work.

Seated in as easy a posture as she can find out-of-doors or in, her splints around her in vessels of water (the water for keeping them pliant), and an adequate supply of the broom-corn, or grass-stem, filling at hand, she rapidly makes the coiled button that is the center, the starting point of her basket. Her awl is the thigh-bone of a rabbit, unless she has yielded so far to the pressure of civilization as to use a steel awl secured at the trader's store for the purpose. Stitch by stitch the coil grows, each one sewed, by making a hole with the awl through the coil already made, to that coil. When the time comes for the introduction of the colored splint, she works on as certainly, surely and deftly as before. There is no hesitation. All is mapped out, the stitches counted, long before, and though to the outsider there is no possible resemblance discernible between what she is doing with anything known in the heavens above, the earth beneath, or the waters under the earth, the aboriginal weaver goes on with perfect confidence, seeing clearly the completed and artistic product of her brain and fingers.

One of the Portable Houses bought by the U. S. Indian Department. The rear house was erected by the Indians themselves, and is the home of Senora Salvadora Valenzuela and her daughters.

Two Pala Indian Maidens.

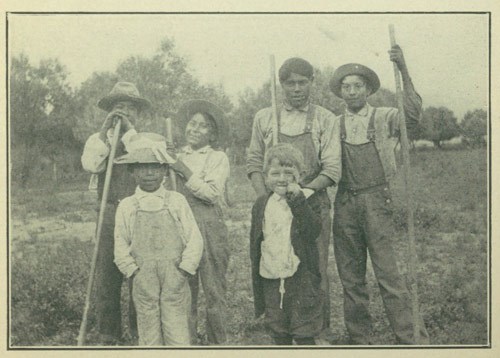

Pala Boys at Work on the Farm.

And how wonderfully those fingers handle the splints. No white woman has ever surpassed, in digital dexterity, these native Indians. Do you wonder? Watch this weaver day after day as her basket grows. A week, two, three, a month, two, three months pass by, and the basket is not yet finished. Time as well as creative skill and digital dexterity are required to make a basket, and it is no uncommon thing to find three, four and even five or six months consumed before the basket is done, and the weaver's heart is secretly rejoiced by the beauty of the work.

Is it surprising that the Indian often refuses to show, even when she knows she can make a sale, the latest product of her skill? The work is the joy of her heart; she has met the true test of the artist—she loves her work and, therefore, joys in it—how can she sell it? So when you ask her if she has a basket to sell she shakes her head, and when, days or weeks later, pressed by a real or fancied necessity, she brings it out and offers it for sale, you inwardly comment—perhaps openly—upon the untruthfulness of the Indian, when, in reality, she meant to the full her negative as to whether she had a basket to sell.

There are many skilful and accomplished basket weavers at Pala, who genuinely love their work. They are preserving for a prejudiced portion of the white race, proofs of an artistic skill possessed for centuries by this despised aboriginal race, and, at the same time, give delight, pleasure, joy and kindlier feelings to those of the white race who feel there is a fundamental truth enunciated in the doctrines of the universal Fatherhood of God, and the Brotherhood of Man.

CHAPTER XIII.

Lace and Pottery Makers

In the preceding chapter I have presented, in a broad and casual manner, the work of the Pala basket-makers. They are not confined, however, to this as their only artistic industry. They engage in other work that is both beautiful and useful. For centuries they have been pottery makers, though, as far as I can learn, they have never learned to decorate their ware with the artistic, quaint, and symbolic designs used by the Zunis, Acomese, Hopis and other Pueblo Indians of Arizona and New Mexico, or that might have been suggested by the designs on their own basketry.

The shapes of their pottery in the main are simple and few, but, when made by skilful hands, are beautiful and pleasing. They make saucers, bowls, jars and ollas. Clay is handled practically in the same way as the materials of basketry. After the clay is well washed, puddled, and softened, it is rolled into a rope-like length. After the center is moulded by the thumbs and fingers of the potter, on a small basket base which she holds in her lap, the clay rope is coiled so as to build up the pot to the desired size. As each coil is added, it is smoothed down with the fingers and a small spatula of bone, pottery or dried gourd skin, the shape being made and maintained by constant manipulation. When completed it is either dried in the sun, or baked over a fire made of dried cow or burro dung, which does not get so hot as to crack the ware, or give out a smoke to blacken it.

In the dressing of skins, and making of rabbit-skin blankets, the older Indians used to be great adepts, but modern materials have taken away the necessity for these things.

Before the Palatinguas were removed from Warner's Ranch to Pala, one of them, gifted with the white man's business sense, and with the creative or inventive faculty, started an industry which he soon made very profitable. Every traveler over the uncultivated and desert area of Southern California has been struck with the immense number of yuccas, Spanish daggers, that seemed to spring up spontaneously on every hand. This keen-brained Indian, José Juan Owlinguwush, saw these, and wiser than some of his smart white brothers, determined to put them to practical and profitable use. He had the bayonets gathered by the hundreds, the thousands. Then he had them beaten, flailed, until the fibres were all separated one from another. The outer skins were thrown away, but the inner fibres were taken and cured. Then, on one of the most primitive spinning-wheels ever designed, and worked by a smiling school-girl, who passed a strap over a square portion of a spindle, at the end of which was a hook, so as to make it revolve at a high degree of speed, the fiber was spun into rope. To the hook the yucca fibre was attached, and as the spindle revolved the hook twisted the fibre into cord. The spinner, with an apron full of the fibre, walked backwards, away from the revolving hook, feeding out the fibre as required and seeing it was of the needed thickness. Some of the rope or cord thus made was dyed a pleasing brown color, and then was woven on a loom, as primitive as was the spinning-wheel, into doormats, which I used, with great satisfaction, for several years.

Soon after the Palatinguas were settled at Pala, the Sybil Carter Association of New York introduced to them, with the full consent of the government officials, the art of Spanish lace-making. In a recent newspaper article it is thus lauded: "Ancient craft [Basket-making] of Pala Indians Gives Place to More Artistic Handiwork." This is a very absurd statement, for wherein is the work of lace-making more artistic than basket-making. In the article that follows our newspaper friend tells us candidly that the creative spirit is still alive in the manufacture of basketry:

They use the natural grasses and no artificial coloring. No two baskets are alike, though the mountain, lightning flash, star, tree, oak-leaf, and snake designs are most common.

The italics are mine. Our writer then goes on to say of the lace-making:

The little ten-year old school-child and the grandmother now sit side by side weaving the intricate figures with deft hands and each receives fair compensation for the finished product. It takes sharp eyes and supple fingers to produce this lace, but no originality, for the Venetian point, Honiton, Torchon, Brussels, Cluny, Milano, Roman Cut-Work and Fillet patterns are supplied by the government teacher, Mrs. Edla Osterberg.

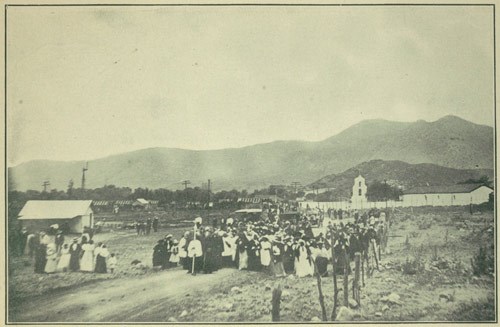

The Fiesta Procession, Leaving the Chapel for the Headgate of the Irrigation Ditch.

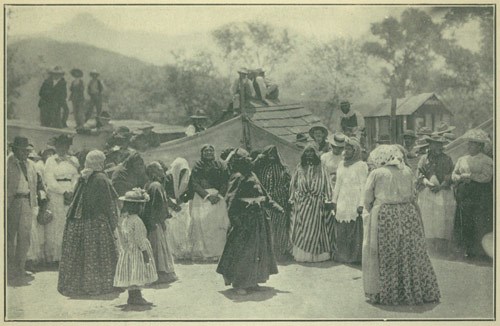

Pala Indian Women Dancing at the Fiesta.

Again the italics are mine. There is no comparison in the art work of basketry and that of lace-making, yet it is a good thing the latter has been introduced. It brings these poor people money easier and quicker than basket-making, and, as they must earn to live, it aids them in the struggle for existence.

In the lace work-room, the last time I was there, thirty-nine weavers in all, varying from bright-eyed children of seven years, to aged grandmothers, were intently engaged upon the delicate work. The bobbins were being twisted and whirled with incredible rapidity and sureness, in the cases of the most expert, and all were as interested as could possibly be.

CHAPTER XIV.

The Religious and Social Life of the Palas

It would require many pages of this little book even to suggest the various rites, ceremonies and ideas connected with the ancient religion of the Palas. It was a strange mixture of Nature worship, superstition, and apparently meaningless rites, all of which, however, clearly revealed the childlike worship of their minds. In the earliest days their religious leaders gained their power by fasting and solitude. Away in the desert, or on the mountain heights, resolutely abstaining from all food, they awaited the coming of their spirit guides, and then, armed with the assurance of direct supernatural control, they assumed the healing of the sick and the general direction of the affairs of the tribe.

Then, later, this simple method was changed. The neophytes sought visions by drinking a decoction made from the jimpson weed—toloache—and though the older and purer-minded men condemned this method it was gaining great hold upon them when the Franciscan Missionaries came a century or so ago.

Even now some of their ceremonies at the period of adolescence, especially of girls, are still carried on. One of these consists of digging a pit, making it hot with burning wood coals, and then "roasting" the maiden therein, supposedly for her physical good.

I have also been present at some of their ancient dances which are still performed by the older men and women. These are petitions to the Powers that control nature to make the wild berries, seeds and roots grow that they may have an abundance of food, and many white men have seen portions of the eagle and other dances, the significance of which they had no conception of. Yet all of these dances had their origin in some simple, childlike idea such as that the eagle, flying upwards into the very eye of the sun, must dwell in or near the abode of the gods, and could therefore convey messages to them from the dwellers upon Earth. This is the secret of all the whisperings and tender words addressed to the eagle before it is either sent on its flight or slain—for in either case it soars to the empyrean. These words are messages to be delivered to the gods above, and are petitions for favors desired, blessings they long for, or punishments they wish to see bestowed upon their enemies.

But when the padres came the major part of the ancestors of the present-day Palas came under their influence. They were soon baptized into the fold of the Catholic Church. The fathers were wise in their tolerance of the old dances. Wherein there was nothing that savored of bestiality, sensuality, or direct demoralization, they raised no objection, hence the survival of these ceremonies to the present day. But, otherwise, the Indians became, as far as they were mentally and spiritually able, good sons and daughters of the church.

Of the good influence these good men had over their Indian wards there can be no question.

A true shepherd of his heathen flock was Padre Peyri. When the order of secularization reached San Luis Rey and every priest was compelled to take the oath of allegiance to the republic of Mexico, Peyri refused to obey. He was ordered out of the country. At first he paid no attention to the command, but when, finally, his superiors in Mexico authorized his obedience, he stole away during the dead of night in January, 1832, in order to save himself and his beloved though dusky wards the pain of parting. It is said that when the Indians discovered that he had left them and was on his way to San Diego in order to take ship for Spain, five hundred of them followed him with the avowed intention of trying to persuade him to return. But they reached the bay at La Playa just as his ship was spreading sail and putting out to sea. A plaintive cry rose heavenward while they stood, their arms outstretched in agonized pleading, as their beloved padre gave them a farewell blessing and his vessel faded away in the blue haze off Point Loma.

The last resident missionary at San Luis Rey was Padre Zalvidea, who died early in 1846.

From this date the decline of the Mission was very rapid. In 1826, the Indian population was 2,869 and in 1846 it scarcely numbered 400. After the death of Padre Zalvidea the poor Indians were like a flock of sheep without a shepherd. They dispersed in every direction, a prey of poverty, disease, and death.

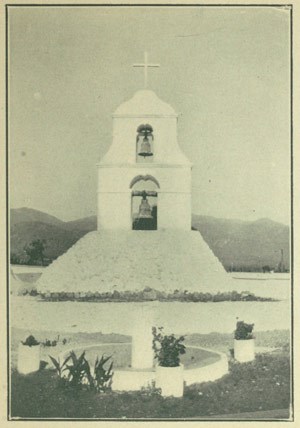

The Pala Campanile After Rebuilding in 1916.

A Pala Basket-Maker at Work.

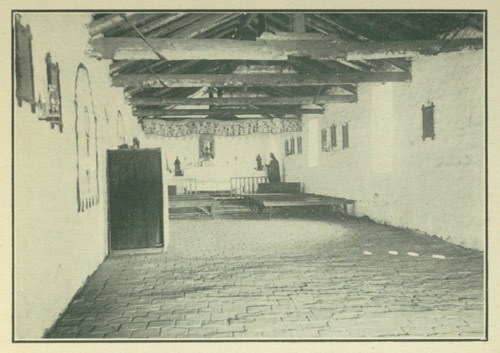

The Interior of Pala Chapel After the Restoration.

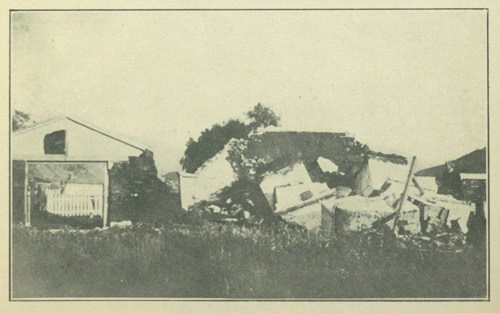

The Ruins of the Pala Campanile, After Its Fall in January, 1916.

The Pala outpost shared the fate of the mother mission, San Luis Rey. It became a prey to the elements and to vandalism. It was soon a ruin, uninhabited and unhabitable. Even the water ditch, not being kept in repair, soon became useless. Thus matters stood until the United States decided to remove the Indians living on Warner's Ranch to Pala.

Longevity used to be quite common among the Pala and other Indians. To attain the age of a hundred years was nothing uncommon, and some lived to be a hundred and fifty and even more years old. A short time ago Leona Ardilla died at Temecula, which, like Pala, used to be a part of the Mission of San Luis Rey. Leona was computed to be fully 113 years old. She well remembered Padre Peyri,—el buena padre, she called him,—and could tell definitely of his going away, of the Indians following him to San Diego, and their grief that they could not bring him back. Often have I heard her tell the story of the eviction of the Indians from San Pasqual, as described in Ramona, and the struggle her people had for the necessities of life after that disastrous event.

Of gentle disposition, uncomplaining regarding the many and great wrongs done her people by the white man, she lived a simple Indian life, eating her porridge of weewish, the bellota of the Spanish, that is, acorn. This was for years her staple food. She ate it as she worked on her baskets, with the prayers on her lips which were taught her by Padre Peyri.

Though deaf and nearly blind for over 20 years, Leona sat daily in the open with some boughs at her back, the primitive, unroofed break-wind described as the only habitation of many of the Indians at the advent of the spiritual conquistadores of California. There, in the shade of her kish, she sat and wove baskets. A few days before she died she tried to finish a basket which had been begun over a month before, but her death intervened and it remains unfinished.

A year hence, when the Indians hold their memorial dance of the dead, this basket will be burned, together with whatever articles of clothing she may have left.

The old basket maker's only living child was Michaela. She is 80 years of age, and was at her mother's death-bed.

After their removal to Pala the Indians were too stunned to pay much attention to anything except their own troubles, and the priest that was sent to them neither knew or understood them. But a few years ago the Reverend George D. Doyle was appointed as their pastor. He entered into the work with zeal, sympathy and love, and in a short time he had won their fullest confidence by his tender care of their best interests. He deems no sacrifice too great where his services are needed. He says, however, that beneficial service would have been rendered impossible save for the justice, tolerance and helpfulness on the part of the Indian service both at Washington and in the field.

In their school life Miss Salmons has their confidence equally with their pastor. The growing generation is bright and learns things just as quickly as white children of the same age.

The older Indians never seem to be able to count. Their difficulty in understanding figures is shown when they make purchases at the reservation store. An old Indian will buy a pound of sugar, for instance, and lay down a dollar. After he is given his change he may buy a pound of bacon and again wait for his change before he makes the next purchase. He simply cannot understand that 100 minus 5 minus 18 leaves 77.

But the younger generation will have no such trouble. They are fairly quick at figures, and a class in mental arithmetic under Miss Salmons' direction would not appear poorly in competition with any white class in any other California school.

The women spend much time in their gardens and in basket- and lace-making. Their houses, gates, and fences are covered with a wealth of roses and other flowers and vines and their little gardens are laid out and cultivated with great skill. The men have a club-house, in which is a billiard-table, where they play pool and other games. There is also a piano, and several of the Indians are able to play creditably at their community dances.

The games most popular among the Palas, in fact among all the Mission Indians, are Gome, Pelota, Peon and Monte. Gome is a test of speed, endurance, and accuracy. As many contestants as wish enter, each barefooted and holding a small wooden ball. A course from one to five miles is designated. When the signal is given each player places his ball upon the toes of his right foot and casts it. The ball must not be touched by the hand again but scooped up by the toes and cast forward. The runner whose ball first passes the line at the end of the course is the winner. The good gome player is expert at scooping the ball whilst running at full speed and casting the same without losing his stride. Casts of 40 to 50 yards are not unusual.

Pelota is a mixture of old time shinny or hocky, la-crosse and foot-ball. It is played by two teams generally twelve on a side, on a field about twice the size of the regulation football gridiron, with two goal posts at each end. Each player is armed with an oak stick about three feet in length. The teams, facing each other, stand in mid-field. The referee holds a wooden ball two inches in diameter which he places in a hole in the ground between the players. He then fills the hole with sand, signals, by a call, and immediately the sticks of the players dig the ball from the sand and endeavor to force it towards and through their opponents' goal. There are no regulations as to interference. Any player may hold, throw or block his opponent. He may snap his opponent's stick from him and hurl it yards away. He may hide the ball momentarily, to pass it to one of his team-mates, always striving for a clean smash at the ball. He may not run with the ball but is allowed three steps in any direction for batting clearance—if he can get it. When one team succeeds in placing the ball between its opponents' goal-posts one point is scored. The first team to score two points wins the contest.

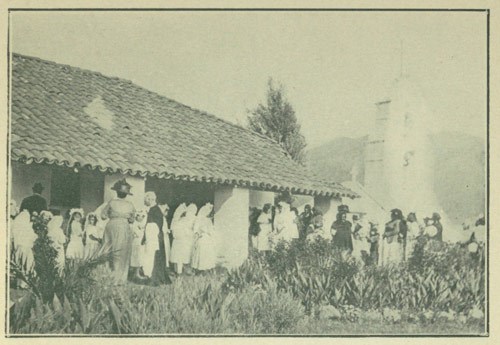

The Opening of the Fiesta. Father G. D. Doyle Reciting the Mass.

On the Morning of the Fiesta at Pala.

The Women in the Ramada at the Pala Fiesta.

Peon, without doubt, is the favorite diversion of the Southern California Indian. It is played at night. A small fire is lighted and four players squat on one side of it and four on the other. The players of one set hold in their hand two sticks or bones, one black, the other white, connected by a thong about fourteen inches long. Two blankets, dirty or clean, it matters little, are spread, one in front of each set. Back of the players are grouped the Indian women, and when the players holding the peon sticks bend forward to grasp the blanket between their teeth the women begin a chant or song. The players, with hands hidden beneath the blanket, suddenly rise to their knees drop the blanket from their teeth and are seen to have their arms folded so closely that it is impossible to tell which hand holds the black stick and which the white one. Their bodies move from side to side, or up and down, keeping perfect time with the song, whilst one of the opponents tries to tell, by false motions or by watching the eyes across the fire, which hands hold the white stick. By a movement of the hand he calls his guess and silence follows the opening of the hand which reveals whether he has been successful in his guess. The players who have been guessed throw their peon sticks across to their opponents. For the ones not guessed a chip or short stick is laid in front of the player. The opponent must continue until he guesses all the hands, when his side goes through the same performance. There are fourteen chips and one set or side must be in possession of all of them before the game is concluded; so it may be seen that it can last many hours. Sometimes the early morning finds the singers and players weary but undaunted, as the game is unfinished, and each side is reluctant to give up without scoring.

As poker is called the American's gambling game so peon might be named the Indian's gambling game. Large sums are said to have been wagered on this game prior to February of 1915, when the Commissioner of Indian Affairs placed the ban upon gambling of any description on the reservations. The game is now played only for a prize or small purse which is offered by the Fiesta Committee.