полная версия

полная версияPicturesque Pala / The Story of the Mission Chapel of San Antonio de Padua Connected with Mission San Luis Rey

So the people brought pivat—a native tobacco that grows in Southern California—and Uuyot brought the big ceremonial pipe which he had made out of rock, and he soon made the big smoke and blew the smoke up into the heavens while he urged the people to dance. They danced hour after hour, until they grew tired, and Uuyot smoked all the time, but still he urged them to dance.

Then he called out again to 'Those Above:' 'Witiako!' but could obtain no response. This made him sad and disconsolate, and when the people saw Uuyot sad and disconsolate they became panic-stricken, ceased to dance and clung around him for comfort and protection. But poor Uuyot had none to give. He himself was the saddest and most forsaken of all, and he got up and bade the people leave him alone, as he wished to walk to and fro by himself. Then he made the people smoke and dance, and when they rested they knelt in a circle and prayed. But he walked away by himself, feeling keenly the refusal of 'Those Above' to speak to him. His heart was deeply wounded.

But, as the people prayed and danced and sang, a gentle light came stealing into the sky from the far, far east. Little by little the darkness was driven away. First the light was grey, then yellow, then white, and at last the glittering brilliancy of the sun filled all the land and covered the sky with glory. The sun had arisen for the first time, and in its light and warmth my people knew they had the favor of 'Those Above,' and they were contented and happy.

But when Siwash, the god of earth, looked around and saw everything revealed by the sun, he was discontented, for the earth was bare and level and monotonous and there was nothing to cheer the sight. So he took some of the people and of them he made high mountains, and of some smaller mountains. Of some he made rivers and creeks and lakes and waterfalls, and of others, coyotes, foxes, deer, antelope, bear, squirrel, porcupines and all the other animals. Then he made out of other people all the different kinds of snakes and reptiles and insects and birds and fishes. Then he wanted trees and plants and flowers, and he turned some of the people into these things. Of every man or woman that he seized he made something according to its value. When he had done he had used up so many people he was scared. So he set to work and made a new lot of people, some to live here and some to live everywhere. And he gave to each family its own language and tongue and its own place to live, and he told them where to live and the sad distress that would come upon them if they mixed up their tongues by intermarriage. Each family was to live in its own place and while all the different families were to be friends and live as brothers, tied together by kinship, amity and concord, there was to be no mixing of bloods.

Thus were settled the original inhabitants on the coast of Southern California by Siwash, the god of the earth, and under the captaincy of Uuyot.

The language of the Palas is simple, easy to pronounce, regular in its grammar, and much richer in the number of its words than is usually believed of Indian idioms. It comprises nearly 5,000 different words, or more than the ordinary vocabulary of the average educated white man or newspaper writer. The gathering of these words was done by the late P. S. Spariman, for years Indian trader and storekeeper, at Rincon, who was an indefatigable student of both words and grammar. His manuscript is now in the keeping of Professor Kroeber, and will shortly be published by the University of California. Dr. Kroeber claims that it is one of the most important records ever compiled of the thought and mental life of the native races of California.

CHAPTER IV.

The Pala Campanile

Every lover of the artistic and the picturesque on first seeing the bell-tower of Pala stands enraptured before its unique personality. And this word "personality" does not seem at all misapplied in this connection. Just as in human beings we find a peculiar charm in certain personalities that it is impossible to explain, so is it with buildings. They possess an individuality, quality, all their own, which, sometimes, eludes the most subtle analysis. Pala is of this character. One feels its charm, longs to stand or sit in contemplation of it. There is a joy in being near to it. Its very proximity speaks peace, contentment, repose, while it breathes out the air of the romance of the past, the devoted love of its great founder, Peyri, the pathos of the struggles it has seen, the loss of its original Indians, its long desertion, and now, its rehabilitation and reuse in the service of Almighty God by a band of Indians, ruthlessly driven from their own home by the stern hand of a wicked and cruel law to find a new home in this gentle and secluded vale.

As far as I know or can learn, the Pala Campanile, from the architectural standpoint, is unique. Not only does it, in itself, stand alone, but in all architecture it stands alone. It is a free building, unattached to any other. The more one studies the Missions from the professional standpoint of the architect the more wonderful they become. They were designed by laymen—using the word as a professed architect would use it. For the padres were the architects of the Missions, and when and where and how could they have been trained technically in the great art, and the practical craftsmanship of architecture? Laymen, indeed, they were, but masters all the same. In harmonious arrangement, in bold daring, in originality, in power, in pleasing variety, in that general gratification of the senses that we feel when a building attracts and satisfies, the priestly architects rank high. And, as I look at the Pala Campanile, my mind seeks to penetrate the mind of its originator. Whence conceived he the idea of this unique construction? Was it a deliberate conception, viewed by a poetic imagination, projected into mental cognizance before erection, and seen in its distinctive beauty as an original and artistic creation before it was actually visualized? Or was it mere accident, mere utilitarianism, without any thought of artistic effect? We must remember that, to the missionary padres, a bell-tower was not a luxury of architecture, but an essential. The bells must be hung up high, in order that their calling tones could penetrate to the farthest recesses of the valley, the canyons, the ravines, the foothills, wherever an Indian ear could hear, an Indian soul be reached. Indians were their one thought—to convert them and bring them into the fold of Mother Church their sole occupation. Hence with the chapel erected, the bell-tower was a necessary accompaniment, to warn the Indian of services, to attract, allure and draw the stranger, the outsider, as well as to remind those who had already entered the fold. In addition its elevation was required for the uplifting of the cross—the Emblem of Salvation.

It is evident, from the nature of the case, that here was no great and studious architectural planning, as at San Luis Rey. This was merely an asistencia, an offshoot of the parent Mission, for the benefit of the Indians of this secluded valley, hence not demanding a building of the size and dignity required at San Luis. But though less important, can we conceive of it as being unimportant to such a devoted adherent to his calling as Padre Peyri? Is it not possible he gave as much thought to the appearance of this little chapel as he did to the massive and kingly structure his genius created at the Mission proper? I see no reason to question it. Hence, though it does sometimes occur to me that perhaps there was no such planning, no deliberate intent, and, therefore, no creative genius of artistic intuition involved in its erection, I have come to the conclusion otherwise. So I regard Pala and its free-standing Campanile as another evidence of devoted genius; another revelation of what the complete absorption of a man's nature to a lofty ideal—such, for instance, as the salvation of the souls of a race of Indians—can enable him to accomplish. One part of his nature uplifted and inspired by his passionate longings to accomplish great things for God and humanity, all parts of his nature necessarily become uplifted. And I can imagine that the good Peyri awoke one morning, or during the quiet hours of the night, perhaps after a wearisome day with his somewhat wayward charges, or after a sleep induced by the hot walk from San Luis Rey, with the picture of this completed chapel and campanile in his mind. With joy it was committed to paper—perhaps—and then, hastily was constructed, to give joy to the generations of a later and alien race who were ultimately to possess the land.

On the other hand may it not be possible that the Pala Campanile was the result of no great mental effort, merely the doing of the most natural and simple thing?

Many a man builds, constructs, better than he knows. It has long been a favorite axiom of my own life that the simple and natural are more beautiful than the complex and artificial. Just as a beautiful woman, clothed in dignified simplicity, in the plainest and most unpretentious dress, will far outshine her sisters upon whose costumes hours of thought in design and labor, and vast sums for gorgeous material and ornamentation have been expended, so will the simply natural in furniture, in pottery, in architecture make its appeal to the keenly critical, the really discerning.

Was Peyri, here, the inspired genius, fired with the sublime audacity that creates new and startling revelations of beauty for the delight and elevation of the world, or was he but the humble, though discerning, man of simple naturalness who did not know enough to realize he was doing what had never been done before, and thus, through his very simplicity and naturalness, stumbling upon the daring, the unique, the individualistic and at the same time, the beautiful, the artistic, the competent?

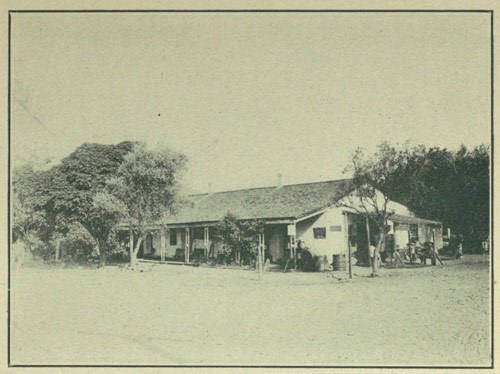

The Store and Ranch-House at Pala.

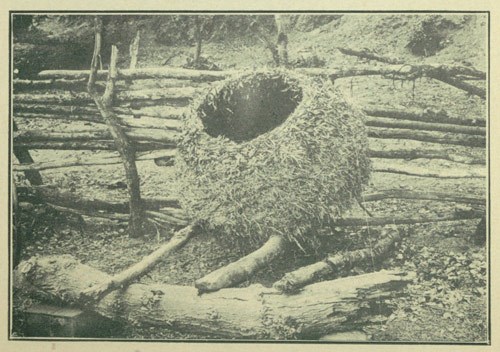

A Suquin, or Acorn Granary, Used by the Pala Indians.

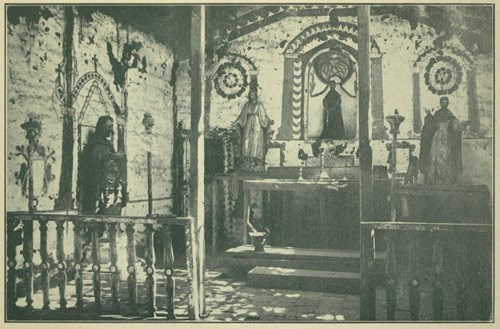

The Old Altar at Pala Chapel, Before the Restoration.

In either case the effect is the same, and, whether built by accident or design, the result of mere utilitarianism or creative genius, the world of the discerning, the critical, and the lovers of the beautifully unique, the daringly original, or the simply natural, owe Padre Peyri a debt of gratitude for the Pala Campanile.

The height of the tower above the base was about 35 feet, the whole height being 50 feet. The wall of the tower was three feet thick.

A flight of steps from the rear built into the base, led up to the bells. They swung one above another, and when I first saw them were undoubtedly as their original hangers had placed them. Suspended from worm-eaten, roughly-hewn beams set into the adobe walls, with thongs of rawhide, one learned to have a keener appreciation of leather than ever before. Exposed to the weather for a century sustaining the heavy weight of the bells, these thongs still do service.

One side of the larger bell bears an inscription in Latin, very much abbreviated, as follows:

Stus Ds Stus Ftis Stus Immortlis Micerere Nobis. An. De 1816 I. R.

which being interpreted means, "Holy Lord, Holy Most Mighty One, Holy Immortal One, Pity us. Year of 1816. Jesus Redemptor."

The other side contains these names in Spanish: "Our Seraphic Father, Francis of Asissi. Saint Louis, King. Saint Clare, Saint Eulalia. Our Light. Cervantes fecit nos—Cervantes made us."

The smaller bell, in the upper embrasure, bears the inscription: "Sancta Maria ora pro nobis"—Holy Mary, pray for us.

The Campanile stands just within the cemetery wall. Originally it appeared to rest upon a base of well-worn granite boulders, brought up from the river bed, and cemented together. The revealing and destroying storm of 1916 showed that these boulders were but a covering for a mere adobe base, which—as evidenced by its standing for practically a whole century—its builders deemed secure enough against all storms and strong enough to sustain the weight of the superstructure. Resting upon this base which was 15 feet high, was the two-storied tower, the upper story terraced, as it were, upon the lower, and smaller in size, as are or were the domes of the Campaniles of Santa Barbara, San Luis Rey, San Buenaventura and Santa Cruz. But at Pala there were no domes. The wall was pierced and each story arched, and below each arch hung a bell. The apex of the tower was in the curved pediment style so familiar to all students of Mission architecture, and was crowned with a cross. By the side of this cross there grew a cactus, or prickly pear. Though suspended in mid-air where it could receive no care, it has flourished ever since the American visitor has known it, and my ancient Indian friends tell me it has been there ever since the tower was built. This assertion may be the only authority for the statement made by one writer that:

One morning just about a century ago, a monk fastened a cross in the still soft adobe on the top of the bell tower and at the foot of the cross he planted a cactus as a token that the cross would conquer the wilderness. From that day to this this cactus has rested its spiny side against that cross, and together—the one the hope and the inspiration of the ages, and the other a savage among the scant bloom of the desert—they have calmly surveyed the labor, the opulence, the decline, and the ruin of a hundred years.

One writer sweetly says of it:

It is rooted in a crack of the adobe tower, close to the spot where the Christian symbol is fixed, and seemed, I thought, to typify how little of material substance is needed by the soul that dwells always at the foot of the cross.

Another story has it that when Padre Peyri ordered the cross placed, it was of green oak from the Palomar mountains. Naturally, the birds came and perched on it, and probably nested at its foot, using mud for that purpose. In this soft mud a chance seed took lodgment and grew.

Be this as it may the birds have always frequented it since I have known it, some of them even nesting in the thorny cactus slabs. On one visit I found a tiny cactus wren bringing up its brood there, while on another occasion I could have sworn it was a mocking-bird, for it poured out such a flood of melody as only a mocking-bird could, but whether the nest there belonged to the glorious songster, or to some other feathered creature, I could not watch long enough to tell.

Other birds too, have utilized this tower from which to launch forth their symphonies and concertos. In the early mornings of several of my visits, I have gone out and sat, perfectly entranced, at the rich torrents of exquisite and independent melody each bird poured forth in prodigal exuberance, and yet which all combined in one chorus of sweetness and joy as must have thrilled the priestly builder, if, today, from his heavenly home he be able to look down upon the work of his hands.

It must not be forgotten, in our admiration for the separate-standing Campanile of Pala, and the general belief that it is the only example in the world, that others of the Franciscan Missions of California practically have the same architectural feature. While the well-known campanile of the Mission San Gabriel is not, in strict fact, a separate standing one, the bell-tower itself is merely an extension of the mission wall and practically stands alone. The same method of construction is followed at Mission Santa Inés. The fachada of the church is extended, to the right, as a wall, which is simply a detached belfry. And, as is well known, the campanile of San Juan Capistrano, erected after the fall of the bell-tower of the grand church in the earthquake of 1812, is a mere wall, closing up a passage between two buildings, with pierced apertures in which the bells are hung.

CHAPTER V.

The Decline of San Luis Rey and Pala

The original purpose of the Spanish Council, as well as of the Church, in founding the Missions of California, was to train the Indians in the ways of Christianity and civilization, and, ultimately, to make citizens of them when it was deemed they had progressed far enough and were stable enough in character to justify such a step.

How long this training period would require none ventured to assert, but whether fifty years, a hundred, or five hundred, the Church undertook the task and was prepared to carry it out.

When, however, the republic of Mexico fell upon evil days and such self-seekers as Santa Anna became president, the greedy politicians of Mexico and the province of California saw an opportunity to feather their own nests at the expense of the Indians. Let the reader for a few moments picture the general situation. Here, in California, there were twenty-one Missions and quite a number of branches, or asistencias. In each Mission from one to three thousand Indians were assembled, under competent direction and business management. It can readily be seen that fields grew fertile, flocks and herds increased, and possessions of a variety of kinds multiplied under such conditions. All these accumulations, however, it must not be forgotten, were not regarded by the padres as their own property, or that of the Church. They were merely held in trust for the benefit of the Indians, and, when the time eventually arrived, were to be distributed as the sole and individual property of the Indians.

Had that time arrived? There is but one opinion in the minds of the authorities, even those who do not in all things approve of the missionaries and their work. For instance, Hittell says:

In other cases it has required hundreds of years to educate savages up to the point of making citizens, and many hundreds to make good citizens. The idea of at once transforming the idle, improvident and brutish natives of California into industrious, law-abiding and self-governing town people was preposterous.

Yet this—the making of citizens of the Indians—was the plea under which the Missions were secularized. The plea was a paltry falsehood. The Missions were the plum for which the politicians strove. Here is what Clinch writes of San Luis Rey:

Under Peyri's administration, despite its disadvantages of soil, San Luis Rey grew steadily in population and material prosperity. In 1800 cattle and horses were six hundred and sheep sixteen hundred. The wheat harvest gave two thousand bushels, but corn and beans were failures and barley only gave a hundred and twenty fanegas. Ten years later 11,000 fanegas of all kinds of grain were gathered as a crop. Cattle had grown to ten thousand five hundred and sheep and hogs nearly ten thousand. The Indians had increased to fifteen hundred. Fourteen hundred and fifty had been baptized while there had been only four hundred deaths recorded. By 1826 the parent mission counted nearly three thousand Christian Indians and nearly a thousand gathered at Pala, six leagues from the central establishment. A church was built there and a priest usually resided at it. At its best time San Luis Rey counted nearly thirty thousand cattle, as many sheep and over two thousand horses as the property of its three thousand Indians. Its average grain crop was about thirteen thousand bushels. San Gabriel surpassed it in farming prosperity with a crop which reached thirty thousand bushels in a year, but in population, in live stock, in the low death rate among its Indians and in the character of its church and buildings, San Luis Rey continued to the end first among the Franciscan missions.

It can well be imagined, therefore, that when the Mexican politicians decided that the time had arrived to secularize the Missions, San Luis Rey would be one of the first to be laid hold of. Pablo de la Portilla and later, Pio Pico, were appointed the commissioners, and it seems to be the general opinion that they were no better than those who operated at the other Missions, and of whom Hittell writes:

The great mass of the commissioners and their officials, whose duty it became to administer the properties of the missions, and especially their great numbers of horses, cattle, sheep and other animals, thought of little else and accomplished little else than enriching themselves. It cannot be said that the spoliation was immediate; but it was certainly very rapid. A few years sufficed to strip the establishments of everything of value and leave the Indians, who were in contemplation of law the beneficiaries of secularization, a shivering crowd of naked, and, so to speak, homeless wanderers upon the face of the earth.

It is almost impossible for one who has not given the matter due study to realize the demoralizing effect upon the Indians and the Mission buildings of this infamous course of procedure. The Indians speedily became the prey of the vicious, the abandoned, the hyenas and vultures of so-called civilization. Deprived of the parental care of the fathers, and led astray on every hand, their corruption spelt speedy extinction, and two or three generations saw this largely accomplished. Only those Indians who were too far away to be easily reached escaped, or partially escaped, the general destruction. The processes were swift, the results lamentably certain.

CHAPTER VI.

The Author of Ramona at Pala

When Helen Hunt Jackson, the gifted author of the romance Ramona—over which hundreds of thousands of Americans have shed bitter tears in deep sympathy with the wrongs perpetrated upon the Indians—was visiting the Mission Indians of California, in 1883, she wrote the following sketch of Pala. This is copied from her California and the Missions, by kind permission of the publishers, Little, Brown & Co., of Boston:

One of the most beautiful appanages of the San Luis Rey Mission, in the time of its prosperity, was the Pala Valley. It lies about twenty-five miles east (twenty miles, Ed.) of San Luis, among broken spurs of the Coast Range, watered by the San Luis River, and also by its own little stream, the Pala Creek. It was always a favorite home of the Indians; and at the time of the secularization, over a thousand of them used to gather at the weekly mass in its chapel. Now, on the occasional visits of the San Juan Capistrano priest, to hold service there, the dilapidated little church is not half filled, and the numbers are growing smaller each year. The buildings are all in decay; the stone steps leading to the belfry have crumbled; the walls of the little graveyard are broken in many places, the paling and the graves are thrown down. On the day we were there, a memorial service for the dead was going on in the chapel; a great square altar was draped with black, decorated with silver lace and ghostly funereal emblems; candles were burning; a row of kneeling black-shawled women were holding lighted candles in their hands; two old Indians were chanting a Latin hymn from a tattered missal bound in rawhide; the whole place was full of chilly gloom, in sharp contrast to the bright valley outside, with its sunlight and silence. This mass was for the soul of an old Indian woman named Margarita, sister of Manuelito, a somewhat famous chief of several bands of the San Luiseños. Her home was at the Potrero,—a mountain meadow, or pasture, as the word signifies,—about ten miles from Pala, high up the mountainside, and reached by an almost impassable road. This farm—or "saeter" it would be called in Norway—was given to Margarita by the friars; and by some exceptional good fortune she had a title which, it is said, can be maintained by her heirs. In 1871, in a revolt of some of Manuelito's bands, Margarita was hung up by her wrists till she was near dying, but was cut down at the last minute and saved.

One of her daughters speaks a little English; and finding that we had visited Pala solely on account of our interest in the Indians, she asked us to come up to the Potrero and pass the night. She said timidly that they had plenty of beds, and would do all that they knew how to do to make us comfortable. One might be in many a dear-priced hotel less comfortably lodged and served than we were by these hospitable Indians in their mud house, floored with earth. In my bedroom were three beds, all neatly made, with lace-trimmed sheets and pillow-cases and patchwork coverlids. One small square window with a wooden shutter was the only aperture for air, and there was no furniture except one chair and a half-dozen trunks. The Indians, like the Norwegian peasants, keep their clothes and various properties all neatly packed away in boxes or trunks. As I fell asleep, I wondered if in the morning I should see Indian heads on the pillows opposite me; the whole place was swarming with men, women, and babies, and it seemed impossible for them to spare so many beds; but, no, when I waked, there were the beds still undisturbed; a soft-eyed Indian girl was on her knees rummaging in one of the trunks; seeing me awake, she murmured a few words in Indian, which conveyed her apology as well as if I had understood them. From the very bottom of the trunk she drew out a gilt-edged china mug, darted out of the room, and came back bringing it filled with fresh water. As she set it in the chair, in which she had already put a tin pan of water and a clean coarse towel, she smiled, and made a sign that it was for my teeth. There was a thoughtfulness and delicacy in the attention which lifted it far beyond the level of its literal value. The gilt-edged mug was her most precious possession; and, in remembering water for the teeth, she had provided me with the last superfluity in the way of white man's comfort of which she could think.