Полная версия

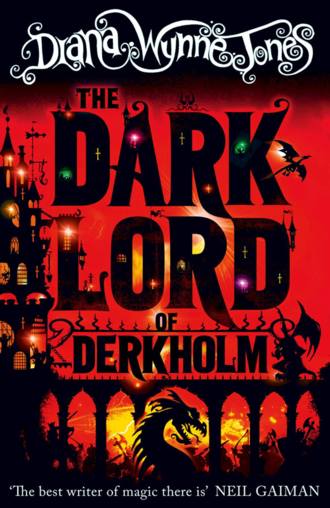

The Dark Lord of Derkholm

“Ah.” Derk looked up to see Umru smiling meaningly.

“I would buy as many as you could grow,” Umru said. He clapped his hands again and the boys brought water and cloths. As Derk washed the pungent juice off his fingers, he realized that he would only need a couple of trees, at two gold for a dozen fruit, to earn the money for that fine. But they might take years to grow. Umru looked sideways at him as they dried their hands, almost uncertainly. “I – er – have another small favour to ask, Wizard, something more along the lines of what you usually do for me.”

“Ask away,” said Derk.

“I need forty or so newly severed heads to go on stakes all over the city when the tours come through,” Umru explained. “This year I am the kind of priest who beheads heretics. Could you—?”

“No trouble at all,” said Derk.

Umru looked so relieved that Derk saw the man had been truly worried in case his refusal to help with the god had annoyed Derk into refusing to work magic for him.

“I promise to move the battles if I can,” Derk assured him.

Umru heaved himself to his feet. “As I said, every man has his sticking-point,” he said, showing Derk he was right.

He led Derk outside and down steep stairs. It was almost like Derk’s usual visits. Up to now, Derk had been feeling quite out of his depth. No one had tried to bribe him before, nor did he know how to deal with Umru’s religious experiences; but there was no uncertainty when it came to putting a spell on a sheep’s head or so. Then he saw what Umru had waiting for him, piled in a small courtyard below. Derk stared at the heap of old yellowy-brown human skulls and swallowed.

“Where—?”

Umru smiled. “We fetched them up from the catacombs. They were all priests once. I hope they don’t worry you.”

“Not at all,” Derk lied.

He took a deep breath and began. It was the sort of thing he was good at and so used to that he could have done it with his eyes shut. Before long, he did have his eyes shut most of the time. The skulls, under his hands, turned back into the people they had once been, but without their bodies. None of them seemed to like the experience. Most of them stared at Derk reproachfully. If he looked away, he saw Umru nodding and smiling cheerfully. Even with his eyes shut, he felt quite ill by the end.

“Nice quantities of blood,” Umru said. “Splendid. Let us hope the weather stays chilly. The usual fee?”

For a second, Derk was tempted to ask for a hundred gold. He felt he had earned it. Umru could afford it. But he could not bear to stand beside the heap of bleeding heads, most of which were still staring at him from half-shut resentful eyes, and bargain. “Usual fee,” he agreed hastily.

He took the money and fled to the main courtyard, where the fanatical men were waiting with Beauty. “This horse is for sale?” one of them asked him greedily.

“No!” Derk snapped. He was still feeling ill as Beauty took off. The surge when she leapt into the air was almost too much for him.

“Home nhow?” Beauty asked hopefully.

Derk swallowed. “No. Take a bit of a swing eastwards. I need to look at the battlefield.” And to calm down, he thought. This had not been a good day.

Beauty obediently swerved out beyond the domes of the city and flapped high above the countryside there. They flew above orderly rows of orchard trees, vines and vegetables that followed the shape of the ground, green fields and stubbled ones, and some fields rich brown and already ploughed, woods, meadows, hedges. Everything was bronze-green and a little hazy in the afternoon light. Everything was beautifully kept. Through it all swung the river in prosperous curves that reminded Derk of Umru’s belly, of his dragon-dolphin and then of his not-to-be mermaid daughter. He told himself sternly that Shona’s idea of an intelligent carrier pigeon was a much more practical one and began to feel a little better. He could see why Umru was anxious not have the battles here. This was some of the best farmland he had ever seen. He would have to move the battlefield. That was one good thing to come out of today – and he had gained a new fruit. But he still had no god and no demon. He sighed.

“Better turn for home,” he told Beauty.

She banked round, wheeling across the river, and set off south, flying much faster. She was always anxious to get back to Pretty. The blue line of the mountains came nearer with every wingbeat. Very shortly, the mountains were a line of individual hills, with craggy places pushing out into the cultivated fields like headlands, dark with heather or grey-green with rough grass. One headland over to the left caught Derk’s eye because it was so green and handsomely wooded with clumps of trees. As Beauty moved nearer to it, he saw a tiny white oblong up there in the midst of the green. It could have been an altar.

“Hang on,” he told Beauty. “Can you land by that white thing just for a moment?”

Beauty’s tail gave a circular swish of protest, but she went obediently planing down to the left and landed softly, deep in long tender grass.

Derk dismounted in a small meadow mostly circled by trees. The leaves were a wonderful array of tinged reds, dark greens and acid autumn yellow. The grass had been mown a little, but not much – just enough to allow the growth of every kind of meadow flower. Bees buzzed among them. Beauty put her head down eagerly and moved off to graze. Derk simply stood for a while. It felt here as if peace was climbing out of the very roots of the grass, moving up through his feet to his body, and filling him with an alert kind of softness. All the worries of being Dark Lord seemed small, and far-off, and easily solved. After a minute or so, he walked over to the white thing. It was an altar, as he had thought, small and plain. Plain letters on its side said Umru gives this to the glory of Anscher.

“I thought this must be the place,” Derk murmured.

It seemed to him that there could be no harm in asking Anscher for help. He began to explain, in an ordinary conversational way, far more calmly than he had explained to Umru, that Mr Chesney demanded a god for this year’s special effect. “And if we don’t produce something,” he said, “nobody gets any pay at all. I know this sounds very worldly, but what it means is that there will be a lot of showy fighting over this good farming country and people will be killed for no reason at all. A great deal of effort going to utter waste, do you see?”

As he went on speaking, Derk had the feeling that he, and the small altar, were the centre of a kind of cone of attention. It was a vast cone, whose point centred on the meadow while the rest went spreading out and out, and up through the sky – or not exactly up, Derk thought: more like outwards, into realms and spaces beyond anything humans could reach. The attentiveness was more alive than anything Derk had ever experienced, and it was strong as a bright light. For a while, he was sure he was being heard. But there was no kind of answer.

“Please,” Derk said. “Can you see your way to doing anything? Anything?”

There was no reply. After a time, though not immediately, he felt the cone very softly and quite kindly going away. He sighed. “Ah well. It was worth a try.” He turned away from the altar and stepped through the grass. And realised he was utterly exhausted. He had never in his life felt so drained. It was an effort to get his feet through the grass.

Beauty looked up as Derk dragged himself over to her. “Nhize ghrass,” she remarked. “Htasty flowers.” Whatever had drained Derk had had the opposite effect on Beauty. He had never seen her eyes so bright or her coat glow so. Every feather in her great black wings gleamed with well-being.

He got himself on to her back by hanging over her, stomach down, and then scrambling. “Home,” he panted and Beauty leapt into the air with a will.

They crossed the mountains. They crossed the moors and then the great magical wastes that were kept mostly for Pilgrims to seem to get lost in, and came finally, near sundown, to the more roughly cultivated land north of Derkholm. By this time Derk was recovering, but still tired enough that, when they saw a crossroads and an inn beside it, he had a sudden longing for a rest and a quiet pint of ale before he went home and faced all the new pigeon messages. He knew this inn. He knew its landlord, Nellsy, and didn’t much care for him. Nellsy was a whinger. But he brewed a good ale.

“Go down by that inn there,” he told Beauty.

She turned her head to fix a large blue-brown eye on him. “Nheed to hsee Prehtty.”

“Soon. I’ll just have one really quick pint,” Derk said.

She sighed and went down into the inn yard.

The two carthorses standing there backed and stamped with mild alarm. They were not used to other horses coming out of the sky. Nellsy bawled at them to stand still. He was hard at work loading the dray the horses were harnessed to with barrels, mugs and chairs. As Derk walked towards the dray, he could see a sofa and a mattress among the load as well.

“Evening, Nellsy,” he said. “What are you doing?”

“Closing the inn down. Getting out,” Nellsy answered. “This is my last load. The wife went with the rest of it this morning. I’m right in the path of the tours here, and I’m not staying to watch the place broken up by werewolves or some such.”

“I think most of the tours are coming into Derkholm from the east,” Derk said, “and the werewolves are programmed to attack in the north. You should be all right here.”

“Can’t rely on that. Bloody Wizard Guides get lost all the time,” Nellsy retorted. “And I’m not hanging round to give them directions either. You wanted a drink?”

“Well, I did,” Derk admitted.

“Go on in. Help yourself. There’s still a last barrel set up,” Nellsy said. “Sorry I can’t stay and serve you, but I’m late on the road as it is. It’ll be dark midnight before I get this lot to the wife’s sister and the sour-faced bitch is going to be in bed and pretending she thought I was coming tomorrow and there’ll be no food saved—”

Derk left Nellsy grumbling and went into the taproom. It was practically empty. All the tables and benches had gone and the fire was out. His boots clumped on the bare floor as he went to the bar. Someone had swept the floor, possibly even scrubbed it. Without its usual coating of sawdust and litter, it was quite handsome oak boards. Derk unhooked the last remaining battered pewter mug and managed to fill it three-quarters full from the barrel before the dregs started coming. Then he clumped outside to sit in the last of the sun and watch Nellsy rope down his load and, finally, leave. Being Nellsy, he left with a lot of shouting, hoof-battering and the squealing of under-greased axles. But he was gone at last. Peace came falling down on the yard as the dust settled. Beauty had found some wispy hay sticking out of the barn wall and was morosely pulling at it. The jingling of her tack made everything even quieter. It was such a small noise.

Derk drank, and felt better, and thought. Ideas seemed to fall through his head like the settling dust. No god then. Only three days to the start of the tours and no demon either. He was going to have to summon a demon himself. Soon. Dangerous. But he had had years of wizardry since his failure over that blue demon, and he thought he now knew enough to manage it, provided there was no one else around to get hurt. He needed somewhere totally deserted with a nice flat floor for chalking the symbols on. Like this inn. It was practically ideal. It was near enough to Derkholm that he could get here translocating in about three hops. And once the demon was there – well – Anscher had quite politely refused his help, but demons were said to take wicked pleasure in pretending to be gods. Suppose he offered the idea to the demon as a reward for guarding the Dark Lord’s Citadel …

Derk poured the rest of his beer on the ground and stood up. Better do it tonight before he lost his nerve. Demons were best summoned at night. Before that, he had to get Beauty out of here and, most importantly, look up in the books exactly how you did summon a demon.

Everyone except Callette was sitting or lying about on the still vast terrace, enjoying the warm sunset. “He’s in,” Blade said. “He made me rub down Beauty.”

“He hasn’t eaten the supper I left him,” said Lydda.

Shona looked up from waxing her travelling harp. “Then he’s probably in his study. I left him at least ten urgent pigeon messages there.”

“I’ll go and interrupt him then,” said Elda.

“You do that,” said everyone, anxious for some peace.

They had just settled down again when Elda shot out through the front door with shrill screams. “He isn’t there! He’s gone to call up a demon! Look!” She held out towards them a fruit that glowed orange in the twilight.

“Since when does an apple mean you’re calling a demon?” Kit wanted to know.

“Stupid! It’s underneath! I’ve got it skewered on my talon!” Elda squawked.

“You dipped your talon in a demon?” Don said.

“Ooh!” Elda yelled. She dropped to sitting position, put the orange fruit carefully down on the terrace, and held out her right set of talons with a piece of paper stuck on the middle one. “Someone get it off for me. Carefully.”

Blade went and worked the paper free. Tipping it into the light from the front door, he read in his father’s scrawling writing, “‘Elda, here’s a new fruit for you. Save me the rind and the pips and I’ll look at your story tomorrow. I’ve got to spend the night at Nellsy’s inn.’ This doesn’t say a word about demons, Elda.”

“Come and see,” Elda said portentously.

Blade looked at Don. “Your turn.”

Don snapped his beak at Blade and stood up. “Where?”

“His study, stupid!” Elda said. She galloped back into the house with Don lazily slinking after her. Blade heard their talons clicking up the stairs and hoped that would be the end of the fuss. It was all typical Elda. He had almost forgotten the matter when Don reappeared, walking on three legs, with his tail lashing anxiously.

“She may be right about the demon,” he announced. “He’s not in the house and he’s left four demonologies and a grimoire open on his desk. Here, Lydda. He left this for you. It was on the grimoire making the page greasy.” He handed Lydda a pastry on a piece of paper.

Lydda rose up on her haunches and took the pasty. She sniffed it. She sliced delicately into the crust with the tip of her beak. “Carrots, basil, eggs,” she murmured low in her throat. “Saffron. Something else I can’t make out. This is elegant

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.