Полная версия

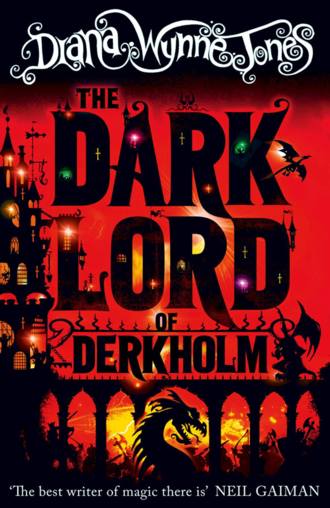

The Dark Lord of Derkholm

“Yes, but how do we get up to the bedrooms?” Derk said, looking up at the ragged hole in the roof. “And Shona’s piano was up on the second floor.”

“It’s still up there,” said Barnabas, “or we’d have met it by now. Better reassemble the stairs, Finn, and slap some kind of roof on, don’t you think? Derk, you’re going to owe us for this.”

“Fine. Thanks,” said Derk. His mind was on Kit. Kit squeezed out through a gap beside the front door and flopped down on his stomach with his head bent almost upside down between his front claws. “My head aches,” he said, “and I hurt all over.” He was a terrible sight. Every feather and hair on him was grey with dust or cobwebs. There was a small cut on one haunch. Otherwise, he seemed to have been lucky.

Derk looked anxiously around for some sign of the others. Mara had gone too, but he could hear her voice somewhere. In the chorus of voices answering, he could pick out Elda, Blade, Lydda, Don and Callette. “Thank goodness,” he said. “You don’t seem to have killed any of the others.”

Kit groaned.

“And you could have done,” added Derk. “You know how heavy you are. Come along to your den and let me hose you down with warm water.”

Kit was far too big to live in the house these days. Derk led the way to the large shed he had made over to Kit, and Kit crawled after him, groaning. He made further long, crooning moans while Derk played the hose over him outside it, but that seemed to be because he had started to feel his bruises. Derk made sure nothing was broken, not even the long, precious flight feathers in Kit’s great wings. Kit grumbled that he had broken two talons.

“Be thankful that was all,” Derk said. “Now, do you want to talk to me out here, or indoors in private?”

“Indoors,” Kit moaned. “I want to lie down.”

Derk pushed open the shed door and beckoned Kit inside. He felt guilty doing it, as if he was prying into Kit’s secrets. Kit did not usually let anyone inside his den. He always claimed it was in too much of a mess, but in fact, as Derk had often suspected, it was neater than anywhere in the house. Everything Kit owned was shut secretly away in a big cupboard. The only things outside the cupboard were the carpet Mara had made him, the huge horsehair cushions Kit used for his bed, and some of Kit’s paintings pinned to the walls.

Kit was too bruised to mind Derk seeing his den. He simply crawled to his cushions, dripping all over the floor, too sore to shake himself dry, and climbed up with a sigh. “All right,” he said. “Talk. Tell me off. Go on.”

“No – you talk,” said Derk. “What did you think you were playing at there with Mr Chesney?”

Kit’s sodden tail did a brief hectic lashing. He buried his beak between two cushions. “No idea,” he said. “I feel awful.”

“Nonsense,” said Derk. “Come clean, Kit. You got the other four to pretend they couldn’t speak and then you sat there in the gateway. Why?”

Kit said something muffled and dire into the cushions.

“What?” said Derk.

Kit’s head came up and swivelled savagely towards Derk. He glared. “I said,” he said, “I was going to kill him. But I couldn’t manage it. Satisfied?” He plunged his beak back among the cushions again.

“Why?” asked Derk.

“He orders this whole world about!” Kit roared. It was loud, even through the horsehair. “He ordered you about. He called Shona a slavegirl. I was going to kill him anyway to get rid of him, but I was glad he deserved it. And I thought if most people there thought the griffins were just dumb beasts, then you couldn’t be blamed. You know – I got loose by accident and savaged him.”

“I’m damn glad you didn’t, Kit,” said Derk. “It’s no fun to have to think of yourself as a murderer.”

“Oh, I knew they’d kill me,” said Kit.

“No, I mean it’s a vile state of mind,” Derk explained. “A bit like being mad, except that you’re sane, I’ve always thought. So what stopped you?” He was shocked to hear himself sounding truly regretful as he asked this question.

Kit reared his head up. “It was when I looked in his face. It was awful. He thinks he owns everything in this world. He thinks he’s right. He wouldn’t have understood. It was a pity. I could have killed him in seconds, even with that demon in his pocket, but he would have been just like food. He wouldn’t have felt guilty and neither would I.”

“I’m glad to hear you think you ought to have felt guilty,” Derk observed. “I was beginning to wonder whether we’d brought you up properly.”

“I do feel guilty. I did,” Kit protested. “And I hated the idea. But I’ve been feeling rather bloodthirsty lately and saving the world seemed a good way to use it. I don’t seem to be much use otherwise. And now,” he added miserably, “I feel terrible about the house too.”

“Don’t. Most of it has to come down anyway – on Mr Chesney’s orders,” Derk said. “So you were crouching in the bushes by the terrace fuelling your bloodlust, were you?”

“Shut up!” Kit tried to squirm with shame and left off with a squawk when his bruises bit. “All right. It was a stupid idea. I hate myself, if that makes you feel any better!”

“Don’t be an ass, Kit.” Derk was thinking things through, fumbling for an explanation. Something had been biting Kit for months. Long before there was any question of Derk becoming the Dark Lord, Kit had been in a foul, tetchy, snarling mood – bloodthirsty, as he called it himself – and Derk had put it down simply to the fact that Kit was now fifteen. But suppose it was more than that. Suppose Kit had a reason to be unhappy. “Kit,” he said thoughtfully, “I didn’t see you at all until you arrived between the gateposts, and when you were there you looked about twice your real size—”

“Did I?” said Kit. “It must have been because you were worried about Mr Chesney.”

“Really?” said Derk. “And I suppose I was just worried again when I distinctly heard you tell me Mr Chesney had a demon in his pocket?”

Kit’s head shot round again and, for a moment, his eyes were lambent black with alarm. Derk could see Kit force them back to their normal golden yellow and try to answer casually. “I expect somebody mentioned it to me. Everyone knows he keeps it there.”

“No. Everybody doesn’t,” Derk told him. “I think even Querida would be surprised to know.” Damn! He hadn’t told Barnabas about that accident yet! “Kit, come clean. You’re another one like Blade, aren’t you? How long have you known you could do magic?”

“Only about a year,” Kit admitted. “About the same time as Blade – Blade thinks we both inherited it from you – but we both seem to do different things.”

“Because of course you’ve compared notes,” said Derk. “Kit, let’s get this straight at once. Even more than Blade, there’s no question of you going to the University—”

Kit’s head flopped forward. “I know. I know they’d keep me as an exhibit. That’s why I didn’t want to mention it.”

“But you must have some teaching,” Derk pointed out, “in case you do something wrong by accident. Mara and I should have been teaching you at the same time as Blade. You ought to have told us, Kit. Let me tell you the same as I told Blade. I will find you a proper tutor, both of you, but you have to be patient, because it takes time to find the right magic user – and you’ll have to be patient for the next year at least, now that I have to be Dark Lord. Can you bear to wait? You can learn quite a bit helping me with that if you want.”

“I wasn’t going to tell you at all,” Kit said.

“So you bit everyone’s head off instead,” Derk said.

Kit’s beak was still stuck among his cushions, but a big griffin grin was spreading round the ends of it. “At least I haven’t been screaming you’re a jealous tyrant,” he said. “Like Blade.”

Well I am, a little, Derk thought. Jealous anyway. You’ve both got your magical careers before you, and you, Kit, have all the brains I could cram into one large griffin head. “True,” he said, sighing. “Now lie down and rest. I’ll give you something for the bruises if they’re still bad this evening.”

He shut the door quietly and went back to the house. Shona met him at the edge of the terrace, indignant and not posing at all. “The younger ones are all safe,” she said. “They were in the dining room. They didn’t even notice the roof coming down!”

“What?” said Derk. “How?”

Shona pointed along the terrace with her thumb. “Look at them!”

Blade sat at the long, littered table. So did Mara, Finn and Barnabas. Lydda and Don were stretched on the flagstones among the empty chairs. Callette was couchant along the steps to the garden, with her tail occasionally whipping the cowering orchids. Elda was crouching along the table itself. Each of them was bent over one of the little flat machines with buttons, pushing those buttons with finger or talon as if nothing else in the world mattered.

“Callette found out how to do this,” Don said.

“She’s a genius,” Barnabas remarked. “I never realised they did anything but add numbers. I made her a hundred of them in case the power packs run out.”

Elda looked up briefly when Derk went to peer across her feathered shoulder. “You kill little men coming down from the sky and they kill you,” she explained. “And we did so notice the roof fall in! The viewscreens got all dusty. Damn. You distracted me and I’m dead.”

“Is Kit all right?” Blade asked. “Hey! I’m on level four now. Beat that!”

“Level six,” Callette said smugly from the steps.

“You would be!” said Blade.

“Level seven,” Finn said mildly. “It seems to stop when you’ve won there. Will the house do like this, Derk?”

The middle section of the house was there again, in a billowy, transparent way. Derk could see the stairs through the wall, also back in place. The piece of roof that had fallen in was there too, hovering slightly like a balloon anchored at four corners. At least it would keep the rain out until it all had to be transformed into ruined towers, Derk supposed.

“It’s fine,” he said. “Thanks.” He put a hand on Barnabas’s arm. “I hate to interrupt, but Querida had an accident a while ago, round by the paddock. I think she broke a couple of bones. She wouldn’t let me see to them. She’s gone home.”

“Oh dear!” said Barnabas. He and Mara came out of their button-pushing trances, looking truly concerned.

“You should have brought her up to the house at once!” Mara said.

“She wouldn’t let me do anything,” Derk explained. “She translocated.”

“She’s done this before,” Barnabas said. “Five years ago some fool Pilgrim broke her wrist and Querida got us all fined by translocating straight home and refusing to come back. We had to do without an Enchantress for the rest of the tours. I think shock takes her that way.”

Finn stood up anxiously. “We’d better go to the University and check.”

Barnabas sighed and got up too. “Yes, I suppose so.”

He and Finn stood there looking at Derk expectantly.

“Oh. Sorry,” Derk said. “What do we owe you for restoring the house?”

The two wizards exchanged looks. “Thought you’d never ask,” said Barnabas. “We’ll accept a bag of coffee each, please.”

“Phew!” said Shona, when the two wizards had finally gone. “I think this was the most upsetting day I’ve ever known. And the tours haven’t even started yet!”

“I should hope not,” said Mara. “There are several thousand things to do before that.”

Derk of course was having to learn the same lists in just two weeks, as well as doing the other things a Dark Lord had to see to. Barnabas paid almost daily visits. He and Derk spent long hours consulting in Derk’s study, and then later that day Derk would rush off, looking harassed, to consult with King Luther or some dragons about what Barnabas had told him. In between, he was busily writing out clues to the weakness of the Dark Lord or answering messages. Carrier pigeons came in all the time with messages. Shona dealt with those when she could, and with the messages for Mara too. Mara before long was rushing off all the time, as busy as Derk, to the house near the Central Wastelands she had inherited from an aunt, which she was setting up as the Lair of the Enchantress.

Parents, it seemed to Blade, always had twice the energy of their children and never seemed to get bored the way he did. It was all most unrestful and he kept out of the way. He spent most days hanging out with Kit and Don in the curving side valley just downhill from Derkholm, basking under a glorious dark blue sky. There Kit lazily preened his feathers, recovering from his bruises, while Don sprawled with the black book in his talons, so that they could test Blade on the rules when any of them remembered to. They did not tell Lydda or Elda where they went because those two might tell Shona. Shona was to be avoided like the plague. If Shona saw any of them she was liable to say, “Don, you exercise the dogs while I do my piano practice.”

Or, “Blade, Dad needs you to water the crops while he sees the Emir.”

Or, “Kit, we want four bales of hay down from the loft – and while you’re at it, Dad says to make a space up there for six new cages of pigeons.”

As Kit feelingly said, it was the “while you’re at it” that was worst. It kept you slaving all day. Shona was very good at ‘while you’re at it’s’. She slid them in at the end of orders like knives to the heart. Those days, when they saw Shona coming, even Kit went small and hard to see.

Shona knew of course and complained loudly. “I’ve put off going to Bardic College,” she went round saying, “where I’d much rather be, in order to help Dad out, and the only other people doing anything are Lydda and Callette.”

“But they’re enjoying themselves,” Elda pointed out. “It’s not my fault I’m no good at things.”

“You’re worse than Callette,” Shona retorted. “I’ve never yet caught Callette being good at anything she doesn’t enjoy. At least the boys are honest.”

Callette was certainly enjoying herself just then. She was making the hundred and twenty-six magical objects for the dragon to guard in the north. Most of the time all that could be seen of her was her large grey-brown rump projecting from the shed that was her den, while the tuft on the end of her tail went irritably bouncing here and there as it expressed Callette’s feelings about the latest object. For Callette had become inspired and self-critical with it. She was now trying to make every object different. She kept appearing in the side-valley to show Blade, Kit and Don her latest collection and demand their honest opinions. And they were, in fact, almost too awed to criticise. Callette had started quite modestly with ten or so assorted goblets and various orbs, but then Don had said – without at all meaning to set Callette off – “Shouldn’t the things light up or something when a Pilgrim picks them up?”

“Good idea,” Callette had said briskly, and spread her wings and coasted thoughtfully away with her bundle of orbs.

The next set of objects lit up like anything, some of them quite garishly, but even Callette was unable to say what they were intended to be. “I call them gizmos,” she said, collecting the glittering heap into a sheet to carry them back to her shed.

Every day after that the latest gizmos were more outlandish. “Aren’t you getting just a bit carried away?” Blade suggested, picking up a shining blue rose in one hand and an indescribable spiky thing in the other. It flashed red light when he touched it.

“Probably,” said Callette. “I think I’m like Shona when she can’t stop playing the violin. I keep getting new ideas.”

The one hundred and ninth gizmo caused even Kit to make admiring sounds. It was a lattice of white shapes like snowflakes that chimed softly and turned milky bright when any of them touched it. “Are you sure you’re not really a wizard?” Kit asked, turning the thing respectfully around between his talons.

Callette shot him a huffy look over one brown-barred wing. “Of course not. It’s electronics. It’s what those button-pushing machines work by. I got Barnabas to multiply me another hundred of them and took them apart for the gizmos. Give me that one back. I may keep it. It’s my very best.”

Carrying the gizmo carefully, she took off to glide down the valley. At the mouth of it, she had to rise hastily to clear a herd of cows someone from the village was driving up into the valley.

That was the end of peace in that valley. The cows turned out to belong to the mayor, who was having them penned up there for safety until the tours were over. Thereafter he and his wife and children were in and out of there several times a day, seeing to the cattle. Don flew out to see if there was anywhere else they could go, but came back glumly with the news that every hidden place was now full of cows, sheep, pigs, hens or goats. The three of them were forced to go and lurk behind the stables, which was nothing like so private.

By that time, Derk’s face had sagged from worry to harrowed misery. He felt as if he had spent his entire life rushing away on urgent, unpleasant errands. Almost the first of these was the one he hated most, and he only got himself through it by concentrating on the new animal he would create. He had to go down to the village and break the news there that Mr Chesney wanted the place in ruins. He hated having to do this so heartily that he snapped at Pretty while he was saddling Pretty’s mother Beauty. And Pretty minced off in a sulk and turned the dogs among the geese in revenge. Derk had to sort that out before he left.

“Can’t you control that foal of yours?” he said to Beauty. Beauty had waited patiently through all the running and shouting, merely mantling her huge glossy black wings when Derk came back, to show him she was ready and waiting.

“Ghett’n htoo mhuch f’mhe,” she confessed. She did not speak as well as Pretty, even without a bit in her mouth.

To Derk, Beauty meant as much as the hundred and ninth gizmo did to Callette. He would have died rather than part with Beauty to the University. So he smiled and patted her shining black neck. Not ants, he thought. Not insects at all. Something even more splendid than Beauty. And when he mounted and Beauty bunched her quarters and rose into the air rather more easily even than Kit did, he felt tight across the chest with love and pride. As they sailed down the valley, he considered the idea of a water creature. He had not done one of those yet. Suppose he could get hold of some cells from a dolphin …

He landed in the centre of the village to find nearly every house there being knocked down. “What the hell’s going on?” he said.

The mayor left off demolishing the village shop and came to lean on his sledgehammer by Beauty’s right wing. “Glad to see you, Derk. We were going to need to speak to you about the village hall. We want to leave that standing if we can, but we don’t want any Pilgrims or soldiers messing about in it destroying things. I wondered if you could see a way of disguising it as a ruin.”

“Willingly,” said Derk. “No problem.” The hall had been built only last spring. “But how did you know – how are you going to live with all the houses down?”

“Everyone in the world knows what to expect when the tours come through,” the mayor replied. “Not your fault, Derk. We knew the job was bound to come your way in time. We had pits dug for living in years ago, roofed over, water piped in, cables laid. Furniture and food got moved down there yesterday. Place is going to look properly abandoned by tomorrow, but we’re leaving Tom Holt’s pigsty and Jenny Wellaby’s wash house standing. I heard they expect to find a hovel or two. But I can tell you,” he said, running a hand through the brickdust in his hair, “I didn’t expect these pulled-down houses to look so new. That worries me a lot.”

“I can easily age them a bit for you,” Derk offered.

“And blacken them with fire?” the mayor asked anxiously. “It would look better. And we’ve told off two skinny folk – Fran Taylor and Old George – to pick about in the ruins whenever a tour arrives, to make like starving survivors, you know, but I’d be glad if you could make them look a little less healthy – emaciated, sort of. One look at Old George at the moment and you’d know he’s never had a day’s illness in his life. Can you sicken him up a bit?”

“No problem,” said Derk. The man thought of everything!

“And another thing,” said the mayor. “We’ll be driving all the livestock up the hills to the sides of the valley and penning them up for safety – don’t want any animals getting killed – but if you could do something that makes them hard to see, I’d be much obliged.”

Derk felt he could hardly refuse. He spent the rest of that day adding wizardry to the blows of the sledgehammers and laying the resulting brick dust around as soot. By sunset, the place looked terrible. “What do you think of all this?” Derk asked Old George while he was emaciating him.

Old George shrugged. “Way to earn a living. Stupid way, if you ask me. But I’m not in charge, am I?”

Neither am I, Derk thought as he went to mount Beauty. The frightening thing was that there was nothing he could do about it, any more than Old George could.

Beauty, rattling her wings and snorting to get rid of the dust, gave it as her opinion that this was not much of a day. “Bhoring. No fhlying.”

“You wait,” Derk told her.

Next day he flew north to see King Luther. The day after he went south to an angry and inconclusive meeting with the Marsh Dwellers, who wanted more pay for pretending to sacrifice Pilgrims to their god. He flew home with “Is blasphemy, see, is disrespect for god!” echoing in his ears, wistfully wondering if his water creature might be something savage that fed exclusively on Marsh people. But the next day, flying east to look at the ten cities scheduled to be sacked, he took that back in favour of something half dolphin, half dragon that lived in a river. The trouble was that there were no big rivers near Derkholm. The day after that, flying south-east to talk to the Emir, he decided something half dragon would be too big.

The Emir was flatly refusing to be the Puppet King the lists said he should be. “I’ll be anything else you choose,” he told Derk, “but I will not have my mind enslaved to this tiara. I have seen Sheik Detroy. He is still walking like a zombie after last year. He drools. His valet has to feed him. It’s disgusting! These magic objects are not safe.”

Derk had seen Sheik Detroy too. He felt the Emir had a point. “Then could you perhaps get one of your most devoted servants to wear the tiara for you?”

“And have him usurp my throne?” the Emir said. “I hope you joke.”

They argued for several hours. At length Derk said desperately, “Well, can’t you wear a copy of the tiara and act being enslaved to it?”

“What a good idea!” said the Emir. “I rather fancy myself as an actor. Very well.”

Derk flew home tired out and, as often happened when he was tired, he got his best idea for animal yet. Not an animal. Something half human, half dolphin. A mermaid daughter, that was it. As Beauty wearily flapped onwards, Derk turned over in his mind all the possible ways of splicing dolphin to human. It was going to be fascinating. The question was, would Mara agree to be the mother of this new being? If he presented the idea to her as a challenge, it might be a way of bridging the chilly distance that seemed to have opened up between them.