полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 12, No. 70, August, 1863

The toasts now began in the customary order, attended with speeches neither more nor less witty and ingenious than the specimens of table-eloquence which had heretofore delighted me. As preparatory to each new display, the herald, or whatever he was, behind the chair of state, gave awful notice that the Right Honorable the Lord-Mayor was about to propose a toast. His Lordship being happily delivered thereof, together with some accompanying remarks, the band played an appropriate tune, and the herald again issued proclamation to the effect that such or such a nobleman, or gentleman, general, dignified clergyman, or what not, was going to respond to the Right Honorable the Lord-Mayor's toast; then, if I mistake not, there was another prodigious flourish of trumpets and twanging of stringed instruments; and finally the doomed individual, waiting all this while to be decapitated, got up and proceeded to make a fool of himself. A bashful young earl tried his maiden oratory on the good citizens of London, and having evidently got every word by heart, (even including, however he managed it, the most seemingly casual improvisations of the moment,) he really spoke like a book, and made incomparably the smoothest speech I ever heard in England.

The weight and gravity of the speakers, not only on this occasion, but all similar ones, was what impressed me as most extraordinary, not to say absurd. Why should people eat a good dinner, and put their spirits into festive trim with Champagne, and afterwards mellow themselves into a most enjoyable state of quietude with copious libations of Sherry and old Port, and then disturb the whole excellent result by listening to speeches as heavy as an after-dinner nap, and in no degree so refreshing? If the Champagne had thrown its sparkle over the surface of these effusions, or if the generous Port had shone through their substance with a ruddy glow of the old English humor, I might have seen a reason for honest gentlemen prattling in their cups, and should undoubtedly have been glad to be a listener. But there was no attempt nor impulse of the kind on the part of the orators, nor apparent expectation of such a phenomenon on that of the audience. In fact, I imagine that the latter were best pleased when the speaker embodied his ideas in the figurative language of arithmetic, or struck upon any hard matter of business or statistics, as a heavy-laden bark bumps upon a rock in mid-ocean. The sad severity, the too earnest utilitarianism, of modern life, have wrought a radical and lamentable change, I am afraid, in this ancient and goodly institution of civic banquets. People used to come to them, a few hundred years ago, for the sake of being jolly; they come now with an odd notion of pouring sober wisdom into their wine by way of wormwood-bitters, and thus make such a mess of it that the wine and wisdom reciprocally spoil one another.

Possibly, the foregoing sentiments have taken a spice of acridity from a circumstance that happened about this stage of the feast, and very much interrupted my own further enjoyment of it. Up to this time, my condition had been exceedingly felicitous, both on account of the brilliancy of the scene, and because I was in close proximity with three very pleasant English friends. One of them was a lady, whose honored name my readers would recognize as a household word, if I dared write it; another, a gentleman, likewise well known to them, whose fine taste, kind heart, and genial cultivation are qualities seldom mixed in such happy proportion as in him. The third was the man to whom I owed most in England, the warm benignity of whose nature was never weary of doing me good, who led me to many scenes of life, in town, camp, and country, which I never could have found out for myself, who knew precisely the kind of help a stranger needs, and gave it as freely as if he had not had a thousand more important things to live for. Thus I never felt safer or cozier at anybody's fireside, even my own, than at the dinner-table of the Lord-Mayor.

Out of this serene sky came a thunderbolt. His Lordship got up and proceeded to make some very eulogistic remarks upon "the literary and commercial"—I question whether those two adjectives were ever before married by a copulative conjunction, and they certainly would not live together in illicit intercourse, of their own accord—"the literary and commercial attainments of an eminent gentleman there present," and then went on to speak of the relations of blood and interest between Great Britain and the aforesaid eminent gentleman's native country. Those bonds were more intimate than had ever before existed between two great nations, throughout all history, and his Lordship felt assured that that whole honorable company would join him in the expression of a fervent wish that they might be held inviolably sacred, on both sides of the Atlantic, now and forever. Then came the same wearisome old toast, dry and hard to chew upon as a musty sea-biscuit, which had been the text of nearly all the oratory of my public career. The herald sonorously announced that Mr. So-and-so would now respond to his Right Honorable Lordship's toast and speech, the trumpets sounded the customary flourish for the onset, there was a thunderous rumble of anticipatory applause, and finally a deep silence sank upon the festive hall.

All this was a horrid piece of treachery on the Lord-Mayor's part, after beguiling me within his lines on a pledge of safe-conduct; and it seemed very strange that he could not let an unobtrusive individual eat his dinner in peace, drink a small sample of the Mansion-House wine, and go away grateful at heart for the old English hospitality. If his Lordship had sent me an infusion of ratsbane in the loving-cup, I should have taken it much more kindly at his hands. But I suppose the secret of the matter to have been somewhat as follows.

All England, just then, was in one of those singular fits of panic excitement, (not fear, though as sensitive and tremulous as that emotion,) which, in consequence of the homogeneous character of the people, their intense patriotism, and their dependence for their ideas in public affairs on other sources than their own examination and individual thought, are more sudden, pervasive, and unreasoning than any similar mood of our own public. In truth, I have never seen the American public in a state at all similar, and believe that we are incapable of it. Our excitements are not impulsive, like theirs, but, right or wrong, are moral and intellectual. For example, the grand rising of the North, at the commencement of this war, bore the aspect of impulse and passion only because it was so universal, and necessarily done in a moment, just as the quiet and simultaneous getting-up of a thousand people out of their chairs would cause a tumult that might be mistaken for a storm. We were cool then, and have been cool ever since, and shall remain cool to the end, which we shall take coolly, whatever it may be. There is nothing which the English find it so difficult to understand in us as this characteristic. They imagine us, in our collective capacity, a kind of wild beast, whose normal condition is savage fury, and are always looking for the moment when we shall break through the slender barriers of international law and comity, and compel the reasonable part of the world, with themselves at the head, to combine for the purpose of putting us into a stronger cage. At times this apprehension becomes so powerful, (and when one man feels it, a million do,) that it resembles the passage of the wind over a broad field of grain, where you see the whole crop bending and swaying beneath one impulse, and each separate stalk tossing with the self-same disturbance as its myriad companions. At such periods all Englishmen talk with a terrible identity of sentiment and expression. You have the whole country in each man; and not one of them all, if you put him strictly to the question, can give a reasonable ground for his alarm. There are but two nations in the world—our own country and France—that can put England into this singular state. It is the united sensitiveness of a people extremely well-to-do, most anxious for the preservation of the cumbrous and moss-grown prosperity which they have been so long in consolidating, and incompetent (owing to the national half-sightedness, and their habit of trusting to a few leading minds for their public opinion) to judge when that prosperity is really threatened.

If the English were accustomed to look at the foreign side of any international dispute, they might easily have satisfied themselves that there was very little danger of a war at that particular crisis, from the simple circumstance that their own Government had positively not an inch of honest ground to stand upon, and could not fail to be aware of the fact. Neither could they have met Parliament with any show of a justification for incurring war. It was no such perilous juncture as exists now, when law and right are really controverted on sustainable or plausible grounds, and a naval commander may at any moment fire off the first cannon of a terrible contest. If I remember it correctly, it was a mere diplomatic squabble, which the British ministers, with the politic generosity which they are in the habit of showing towards their official subordinates, had tried to browbeat us for the purpose of sustaining an ambassador in an indefensible proceeding; and the American Government (for God had not denied us an administration of Statesmen then) had retaliated with stanch courage and exquisite skill, putting inevitably a cruel mortification upon their opponents, but indulging them with no pretence whatever for active resentment.

Now the Lord-Mayor, like any other Englishman, probably fancied that War was on the western gale, and was glad to lay hold of even so insignificant an American as myself, who might be made to harp on the rusty old strings of national sympathies, identity of blood and interest, and community of language and literature, and whisper peace where there was no peace, in however weak an utterance. And possibly his Lordship thought, in his wisdom, that the good feeling which was sure to be expressed by a company of well-bred Englishmen, at his august and far-famed dinner-table, might have an appreciable influence on the grand result. Thus, when the Lord-Mayor invited me to his feast, it was a piece of strategy. He wanted to induce me to fling myself, like a lesser Curtius, with a larger object of self-sacrifice, into the chasm of discord between England and America, and, on my ignominious demur, had resolved to shove me in with his own right-honorable hands, in the hope of closing up the horrible pit forever. On the whole, I forgive his Lordship. He meant well by all parties,—himself, who would share the glory, and me, who ought to have desired nothing better than such an heroic opportunity,—his own country, which would continue to get cotton and breadstuffs, and mine, which would get everything that men work with and wear.

As soon as the Lord-Mayor began to speak, I rapped upon my mind, and it gave forth a hollow sound, being absolutely empty of appropriate ideas. I never thought of listening to the speech, because I knew it all beforehand in twenty repetitions from other lips, and was aware that it would not offer a single suggestive point. In this dilemma, I turned to one of my three friends, a gentleman whom I knew to possess an enviable flow of silver speech, and obtested him, by whatever he deemed holiest, to give me at least an available thought or two to start with, and, once afloat, I would trust to my guardian-angel for enabling me to flounder ashore again, He advised me to begin with some remarks complimentary to the Lord-Mayor, and expressive of the hereditary reverence in which his office was held—at least, my friend thought that there would be no harm in giving his Lordship this little sugar-plum, whether quite the fact or no—was held by the descendants of the Puritan forefathers. Thence, if I liked, getting flexible with the oil of my own eloquence, I might easily slide off into the momentous subject of the relations between England and America, to which his Lordship had made such weighty allusion.

Seizing this handful of straw with a death-grip, and bidding my three friends bury me honorably, I got upon my legs to save both countries, or perish in the attempt. The tables roared and thundered at me, and suddenly were silent again. But, as I have never happened to stand in a position of greater dignity and peril, I deem it a stratagem of sage policy here to close the sketch, leaving myself still erect in so heroic an attitude.

THE GEOLOGICAL MIDDLE AGE

I shall pass lightly over the Permian and Triassic epochs, as being more nearly related in their organic forms to the Carboniferous epoch, with which we are already somewhat familiar, while in those next in succession, the Jurassic and Cretaceous epochs, the later conditions of animal life begin to be already foreshadowed. But though less significant for us in the present stage of our discussion, it must not be supposed that the Permian and Triassic epochs were unimportant in the physical and organic history of Europe. A glance at any geological map of Europe will show the reader how the Belgian island stretched gradually in a southwesterly direction during the Permian epoch, approaching the coast of France by slowly increasing accumulations, and thus filling the Burgundian channel; a wide border of Permian deposits around the coal-field of Great Britain marks the increase of this region also during the same time, and a very extensive tract of a like character is to be seen in Russia. The latter is, however, still under doubt and discussion among geologists, and more recent investigations tend to show that this Russian region, supposed at first to be exclusively Permian, is at least in part Triassic.

With the coming in of the Triassic epoch began the great deposits of Red Sandstone, Muschel-Kalk, and Keuper, in Central Europe. They united the Belgian island to the region of the Vosges and the Black Forest, while they also filled to a great extent the channel between Belgium and the Bohemian island. Thus the land slowly gained upon the Triassic ocean, shutting it within ever-narrowing limits, and preparing the large inland seas so characteristic of the later Secondary times. The character of the organic world still retained a general resemblance to that of the Carboniferous epoch. Among Radiates, the Corals were more nearly allied to those of the earlier ages than to those of modern times, and Crinoids abounded still, though some of the higher Echinoderm types were already introduced. Among Mollusks, the lower Bivalves, that is, the Brachiopods and Bryozoa, still prevailed, while Ammonites continued to be very numerous, differing from the earlier ones chiefly in the ever-increasing complications of their inner partitions, which become so deeply involuted and cut upon their margins, before the type disappears, as to make an intricate tracery of very various patterns on the surface of these shells. The most conspicuous type of Articulates continues as before to be that of Crustacea; but Trilobites have finished their career, and the Lobster-like Crustacea make their appearance for the first time. It does not seem that the class of Insects has greatly increased since the Carboniferous epoch; and Worms are still as difficult to trace as ever, being chiefly known by the cases in which they sheltered themselves. Among Vertebrates, the Fishes still resemble those of the Carboniferous epoch, belonging principally to the Selachians and Ganoids. They have, however, approached somewhat toward a modern pattern, the lobes of the tail being more evenly cut, and their general outline more like that of common fishes. The gigantic marsh Reptiles have become far more numerous and various. They continue through several epochs, but may be said to reach their culminating point in the Jurassic and Cretaceous deposits.

I cannot pass over the Triassic epoch without some allusion to the so-called bird-tracks, so generally believed to mark the introduction of Birds at this time. It is true that in the deposits of the Trias there have been found many traces of footsteps, indicating a vast number of animals which, except for these footprints, remain unknown to us. In the sandstone of the Connecticut Valley they are found in extraordinary numbers, as if these animals, whatever they were, had been in the habit of frequenting that shore. They appear to have been very diversified; for some of the tracks are very large, others quite small, while some would seem, from the way in which the footsteps follow each other, to have been quadrupedal, and others bipedal. We can even measure the length of their strides, following the impressions which, from their succession in a continuous line, mark the walk of a single animal.10 The fact that we find these footprints without any bones or other remains to indicate the animals by which they were made is accounted for by the mode of deposition of the sandstone. It is very unfavorable for the preservation of bones; but, being composed of minute sand mixed with mud, it affords an admirable substance for the reception of these impressions, which have been thus cast in a mould, as it were, and preserved through ages. These animals must have been large, when full-grown, for we find strides measuring six feet between, evidently belonging to the same animal. In the quadrupedal tracks, the front feet seem to have been smaller than the hind ones. Some of the tracks show four toes all turned forward, while in others three toes are turned forward and one backward. It happened that the first tracks found belonged to the latter class; and they very naturally gave rise to the idea that these impressions were made by birds, on account of this formation of the foot. This, however, is a mere inference; and since the inductive method is the only true one in science, it seems to me that we should turn to the facts we have in our possession for the explanation of these mysterious footprints, rather than endeavor to supply by assumption those which we have not. As there are no bones found in connection with these tracks, the only way to arrive at their true character, in the present state of our knowledge, is by comparing them with bones found in other localities in the deposits of the same period in the world's history. Now there have never been found in the Trias any remains of Birds, while it contains innumerable bones of Reptiles; and therefore I think that it is in the latter class that we shall eventually find the solution of this mystery.

At that time the region where Lyme-Regis is now situated in modern England was an estuary on the shore of that ancient sea. About forty years ago a discovery of large and curious bones, belonging to some animal unknown to the scientific world, turned the attention of naturalists to this locality, and since then such a quantity and variety of such remains have been found in the neighborhood as to show that the Sharks, Whales, Porpoises, etc., of the present ocean are not more numerous and diversified than were the inhabitants of this old bay or inlet. Among these animals, the Ichthyosauri (Fish-Lizards) form one of the best-known and most prominent groups. They are chiefly found in the Lias, the lowest set of beds of the Jurassic deposits, and seem to have come in with the close of the Triassic epoch. It is greatly to be regretted that all that is known of the Triassic Reptiles antecedent to the Ichthyosauri still remains in the form of original papers, and is not yet embodied in text-books. They are quite as interesting, as curious, and as diversified as those of the Jurassic epoch, which are, however, much more extensively known, on account of the large collections of these animals belonging to the British Museum. It will be more easy to understand the structural relations of the latter, and their true position in the Animal Kingdom, when those which preceded them are better understood. One of the most remarkable and numerous of these Triassic Reptiles seems to have been an animal resembling, in the form of the head, and in the two articulating surfaces at the juncture of the head with the backbone, the Frogs and Salamanders, though its teeth are like those of a Crocodile. As yet nothing has been found of these animals except the head,—neither the backbone nor the limbs; so that little is known of their general structure.

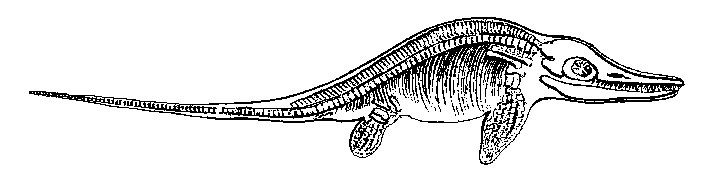

Fig. 1.

The Ichthyosauri (Figure 1) must have been very large, seven or eight feet being the ordinary length, while specimens measuring from twenty to thirty feet are not uncommon. The large head is pointed, like that of the Porpoise; the jaws contain a number of conical teeth, of reptilian form and character; the eyeball was very large, as may be seen by the socket, and it was supported by pieces of bone, such as we find now only in the eyes of birds of prey and in the bony fishes. The ribs begin at the neck and continue to the tail, and there is no distinction between head and neck, as in most Reptiles, but a continuous outline, as in Fishes. They had four limbs, not divided into fingers, but forming mere paddles. Yet fingers seem to be hinted at in these paddles, though not developed, for the bones are in parallel rows, as if to mark what might be such a division. The back-bones are short, but very high, and the surfaces of articulation are hollow, conical cavities, as in Fishes, instead of ball-and-socket joints, as in Reptiles. The ribs are more complicated than in Vertebrates generally: they consist of several pieces, and the breast-bone is formed of a number of bones, making together quite an intricate bony net-work. There is only one living animal, the Crocodile, characterized by this peculiar structure of the breast-bone. The Ichthyosaurus is, indeed, one of the most remarkable of the synthetic types: by the shape of its head one would associate it with the Porpoises, while by its paddles and its long tail it reminds one of the whole group of Cetaceans to which the Porpoises belong; by its crocodilian teeth, its ribs, and its breast-bone, it seems allied to Reptiles; and by its uniform neck, not distinguished from the body, and the structure of the backbone, it recalls the Fishes.

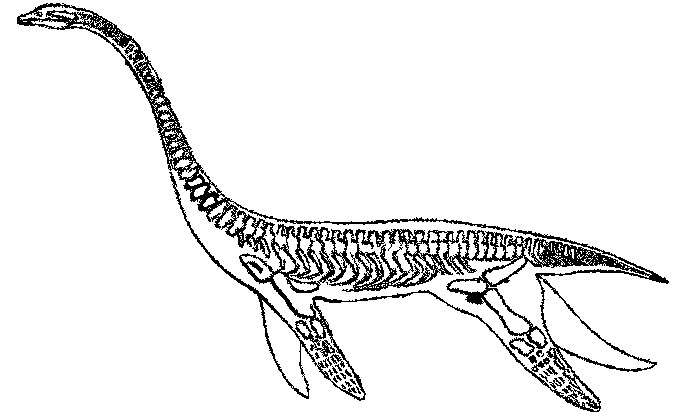

Fig. 2.

Another most curious member of this group is the Plesiosaurus, odd Saurian (Figure 2). By its disproportionately long and flexible neck, and its small, flat head, it unquestionably foreshadows the Serpents, while by the structure of the backbone, the limbs, and the tail, it is closely allied with the Ichthyosaurus. Its flappers are, however, more slender, less clumsy, and were, no doubt, adapted to more rapid motion than the fins of the Ichthyosaurus, while its tail is shorter in proportion to the whole length of the animal. It seems probable, from its general structure, that the Ichthyosaurus moved like a Fish, chiefly by the flapping of the tail, aided by the fins, while in the Plesiosaurus the tail must have been much less efficient as a locomotive organ, and the long, snake-like, flexible neck no doubt rendered the whole body more agile and rapid in its movements. In comparing the two, it may be said, that, as a whole, the Ichthyosaurus, though belonging by its structure to the class of Reptiles, has a closer external resemblance to the Fishes, while the Plesiosaurus is more decidedly reptilian in character. If there exists any animal in our waters, not yet known to naturalists, answering to the descriptions of the "Sea-Serpent," it must be closely allied to the Plesiosaurus. The occurrence in the fresh waters of North America of a Fish, the Lepidosteus, which is closely allied to the fossil Fishes found with the Plesiosaurus in the Jurassic beds, renders such a supposition probable.

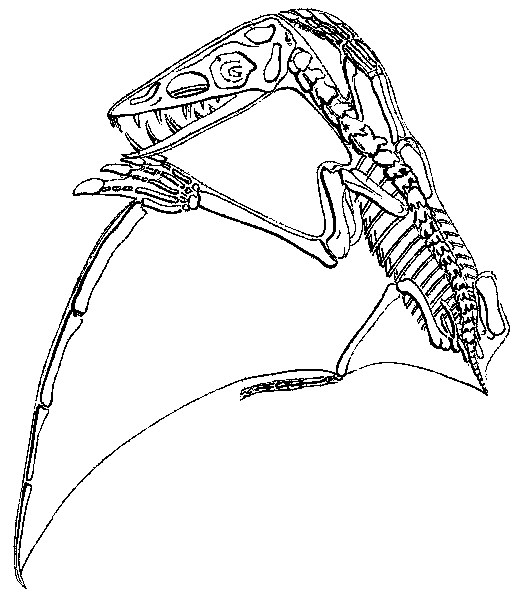

Fig. 3.

Of all these strange old forms, so singularly uniting features of Fishes and Reptiles, none has given rise to more discussion than the Pterodactylus, (Figure 3,) another of the Saurian tribe, associated, however, with Birds by some naturalists, on account of its large wing-like appendages. From the extraordinary length of its anterior limbs, they have generally been described as wings, and the animal is usually represented as a flying Reptile. But if we consider its whole structure, this does not seem probable, and I believe it to have been an essentially aquatic animal, moving after the fashion of the Sea-Turtle. Its so-called wings resemble in structure the front paddles of the Sea-Turtles far more than the wings of a Bird; differing from them, indeed, only by the extraordinary length of the inner toe, while the outer ones are comparatively much shorter. But, notwithstanding this difference, the hand of the Pterodactylus is constructed like that of an aquatic swimming marine Reptile; and I believe, that, if we represent it with its long neck stretched upon the water, its large head furnished with powerful, well-armed jaws, ready to dive after the innumerable smaller animals living in the same ocean, we shall have a more natural picture of its habits than if we consider it as a flying animal, which it is generally supposed to have been. It has not the powerful breast-bone, with the large projecting keel along the middle line, such as exists in all the flying animals. Its breast-bone, on the contrary, is thin and flat, like that of the present Sea-Turtle; and if it moved through the water by the help of its long flappers, as the Sea-Turtle does now, it could well dispense with that powerful construction of the breast-bone so essential to all animals which fly through the air. Again, the powerful teeth, long and conical, placed at considerable intervals in the jaw, constitute a feature common to all predaceous aquatic animals, and would seem to have been utterly useless in a flying animal at that time, since there were no aërial beings of any size to prey upon. The Dragon-Flies found in the same deposits with the Pterodactylus were certainly not a game requiring so powerful a battery of attack.