полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 12, No. 70, August, 1863

The Fishes of the Jurassic sea were exceedingly numerous, but were all of the Ganoid and Selachian tribes. It would weary the reader, were I to introduce here any detailed description of them, but they were as numerous and varied as those living in our present waters. There was the Hybodus, with the marked furrows on the spines and the strong hooks along their margin,—the huge Chimera, with its long whip, its curved bone over the back, and its parrot-like bill,—the Lepidotus, with its large square scales, its large head, its numerous rows of teeth, one within another, forming a powerful grinding apparatus,—the Microdon, with its round, flat body, its jaw paved with small grinding teeth,—the swift Aspidorhynchus, with its long, slender body and massive tail, enabling it to strike the water powerfully and dart forward with great rapidity. There were also a host of small Fishes, comparing with those above mentioned as our Perch, Herring, Smelts, etc., compare with our larger Fishes; but, whatever their size or form, all the Fishes of those days had the same hard scales fitting to each other by hooks, instead of the thin membranous scales overlapping each other at the edge, like the common Fishes of more modern times. The smaller Fishes, no doubt, afforded food to the larger ones, and to the aquatic Reptiles. Indeed, in parts of the intestines of the Ichthyosauri, and in their petrified excrements, have been found the scales and teeth of these smaller Fishes perfectly preserved. It is amazing that we can learn so much of the habits of life of these past creatures, and know even what was the food of animals existing countless ages before man was created.

There are traces of Mammalia in the Jurassic deposits, but they were of those inferior kinds known now as Marsupials, and no complete specimens have yet been found.

The Articulates were largely represented in this epoch. There were already in the vegetation a number of Gymnosperms, affording more favorable nourishment for Insects than the forests of earlier times; and we accordingly find that class in larger numbers than ever before, though still meagre in comparison with its present representation. Crustacea were numerous,—those of the Shrimp and Lobster kinds prevailing, though in some of the Lobsters we have the first advance towards the highest class of Crustacea in the expansion of the transverse diameter now so characteristic of the Crabs. Among Mollusks we have a host of gigantic Ammonites; and the naked Cephalopods, which were in later times to become the prominent representatives of that class, already begin to make their appearance. Among Radiates, some of the higher kinds of Echinoderms, the Ophiurans and Echinolds, take the place of the Crinoids, and the Acalephian Corals give way to the Astræan and Meandrina-like types, resembling the Reef-Builders of the present time.

I have spoken especially of the inhabitants of the Jurassic sea lying between England and France, because it was there that were first found the remains of some of the most remarkable and largest Jurassic animals. But wherever these deposits have been investigated, the remains contained in them reveal the same organic character, though, of course, we find the land Reptiles only where there happen to have been marshes, the aquatic Saurians wherever large estuaries or bays gave them an opportunity of coming in near shore, so that their bones were preserved in the accumulations of mud or clay constantly collecting in such localities,—the Crustacea, Shells, or Sea-Urchins on the old sea-beaches, the Corals in the neighborhood of coral reefs, and so on. In short, the distribution of animals then as now was in accordance with their nature and habits, and we shall seek vainly for them in the localities where they did not belong.

But when I say that the character of the Jurassic animals is the same, I mean, that, wherever a Jurassic sea-shore occurs, be it in France, Germany, England, or elsewhere throughout the world, the Shells, Crustacea, or other animals found upon it have a special character, and are not to be confounded by any one thoroughly acquainted with these fossils with the Shells or Crustacea of any preceding or subsequent time,—that, where a Jurassic marsh exists, the land Reptiles inhabiting it are Jurassic, and neither Triassic nor Cretaceous,—that a Jurassic coral reef is built of Corals belonging as distinctly to the Jurassic creation as the Corals on the Florida reefs belong to the present creation,—that, where some Jurassic bay or inlet is disclosed to us with the Fishes anciently inhabiting it, they are as characteristic of their time as are the Fishes of Massachusetts Bay now.

And not only so, but, while this unity of creation prevails throughout the entire epoch as a whole, there is the same variety of geographical distribution, the same circumscription of faunæ within distinct zoölogical provinces, as at the present time. The Fishes of Massachusetts Bay are not the same as those of Chesapeake Bay, nor those of Chesapeake Bay the same as those of Pamlico Sound, nor those of Pamlico Sound the same as those of the Florida coast. This division of the surface of the earth into given areas within which certain combinations of animals and plants are confined is not peculiar to the present creation, but has prevailed in all times, though with ever-increasing diversity, as the surface of the earth itself assumed a greater variety of climatic conditions. D'Orbigny and others were mistaken in assuming that faunal differences have been introduced only in the last geological epochs. Besides these adjoining zoölogical faunæ, each epoch is divided, as we have seen, into a number of periods, occupying successive levels one above another, and differing specifically from each other in time as zoölogical provinces differ from each other in space. In short, every epoch is to be looked upon from two points of view: as a unit, complete in itself, having one character throughout, and as a stage in the progressive history of the world, forming part of an organic whole.

As the Jurassic epoch was ushered in by the upheaval of the Jura, so its close was marked by the upheaval of that system of mountains called the Côte d'Or. With this latter upheaval began the Cretaceous epoch, which we will examine with special reference to its subdivision into periods, since the periods in this epoch have been clearly distinguished, and investigated with especial care. I have alluded in the preceding article to the immediate contact of the Jurassic and Cretaceous epochs in Switzerland, affording peculiar facilities for the direct comparison of their organic remains. But the Cretaceous deposits are well known, not only in this inland sea of ancient Switzerland, but in a number of European basins, in France, in the Pyrenees, on the Mediterranean shores, and also in Syria, Egypt, India, and Southern Africa, as well as on our own continent. In all these localities, the Cretaceous remains, like those of the Jurassic epoch, have one organic character, distinct and unique. This fact is especially significant, because the contact of their respective deposits is in many localities so immediate and continuous that it affords an admirable test for the development-theory. If this is the true mode of origin of animals, those of the later Jurassic beds must be the progenitors of those of the earlier Cretaceous deposits. Let us see now how far this agrees with our knowledge of the physiological laws of development.

Take first the class of Fishes. We have seen that in the Jurassic periods there were none of our common Fishes, none corresponding to our Herring, Pickerel, Mackerel, and the like,—no Fishes, in short, with thin membranous scales, but that the class was represented exclusively by those with hard, flint-like scales. In the Cretaceous epoch, however, we come suddenly upon a horde of Fishes corresponding to our smaller common Fishes of the Pickerel and Herring tribes, but principally of the kinds found now in tropical waters; there are none like our Cods, Haddocks, etc., such as are found at present in the colder seas. The Fishes of the Jurassic epoch corresponding to our Sharks and Skates and Gar-Pikes still exist, but in much smaller proportion, while these more modern kinds are very numerous. Indeed, a classification of the Cretaceous Fishes would correspond very nearly to one founded on those now living. Shall we, then, suppose that the large reptilian Fishes of the Jurassic time began suddenly to lay numerous broods of these smaller, more modern, scaly Fishes? And shall we account for the diminution of the previous forms by supposing that in order to give a fair chance to the new kinds they brought them forth in large numbers, while they reproduced their own kind less abundantly? According to very careful estimates, if we accept this view, the progeny of the Jurassic Fishes must have borne a proportion of about ninety per cent, of entirely new types to some ten per cent, of those resembling the parents. One would like a fact or two on which to rest so very extraordinary a reversal of all known physiological laws of reproduction, but, unhappily, there is not one.

Still more unaccountable, upon any theory of development according to ordinary laws of reproduction, are those unique, isolated types limited to a single epoch, or sometimes even to a single period. There are some very remarkable instances of this in the Cretaceous deposits. To make my statement clearer, I will say a word of the sequence of these deposits and their division into periods.

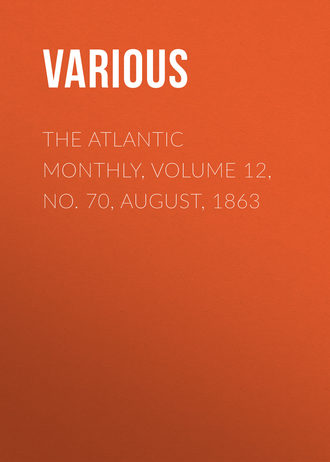

These Cretaceous beds were at first divided only into three sets, called the Neocomian, or lower deposits, the Green-Sands, or middle deposits, and the Chalk, or upper deposits. The Neocomian, the lower division, was afterwards subdivided into three sets of beds, called the Lower, Middle, and Upper Neocomian by some geologists, the Valengian, Neocomian, and Urgonian by others. These three periods are not only traced in immediate succession, one above another, in the transverse cut before described, across the mountain of Chaumont, near Neufchatel, but they are also traced almost on one level along the plain at the foot of the Jura. It is evident that by some disturbance of the surface the eastern end of the range was raised slightly, lifting the lower or Valengian deposits out of the water, so that they remain uncovered, and the next set of deposits, the Neocomian, is accumulated along their base, while these in their turn are slightly raised, and the Urgonian beds are accumulated against them a little lower down. They follow each other from east to west in a narrower area, just as the Azoic, Silurian, and Devonian deposits follow each other from north to south in the northern part of the United States. The Cretaceous deposits have been intimately studied in various localities by different geologists, and are now subdivided into at least ten, or it may be fifteen or sixteen distinct periods, as they stand at present. This is, however, but the beginning of the work; and the recent investigations of the French geologist, Coquand, indicate that several of these periods at least are susceptible of further subdivision. I present here a table enumerating the periods of the Cretaceous epoch best known at present, in their sequence, because I want to show how sharply and in how arbitrary a manner, if I may so express it, new forms are introduced. The names are simply derived from the localities, or from some circumstances connected with the locality where each period has been studied.

Table of Periods in the Cretaceous Epoch.

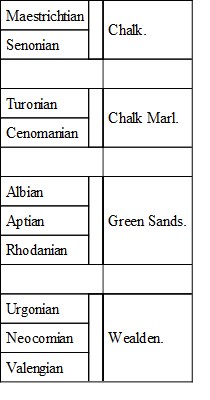

One of the most peculiar and distinct of those unique types alluded to above is that of the Rudistes, a singular Bivalve, in which the lower valve is very deep and conical, while the upper valve sets into to it as into a cup. The subjoined woodcut represents such a Bivalve. These Rudistes are found suddenly in the Urgonian deposits; there are none in the two preceding sets of beds; they disappear in the three following periods, and reappear again in great numbers in the Cenomanian, Turonian, and Senonian periods, and disappear again in the succeeding one. These can hardly be missed from any negligence or oversight in the examination of these deposits, for they are by no means rare. They are found always in great numbers, occupying crowded beds, like Oysters in the present time. So numerous are they, where they occur at all, that the deposits containing them are called by many naturalists the first, second, third, and fourth bank of Rudistes. Which of the ordinary Bivalves, then, gave rise to this very remarkable form in the class, allowed it to die out, and revived it again at various intervals? This is by no means the only instance of the same kind. There are a number of types making their appearance suddenly, lasting during one period or during a succession of periods, and then disappearing forever, while others, like the Rudistes, come in, vanish, and reappear at a later time.

Rudistes.

I am well aware that the advocates of the development-theory do not state their views as I have here presented them. On the contrary, they protest against any idea of sudden, violent, abrupt changes, and maintain that by slow and imperceptible modifications during immense periods of time these new types have been introduced without involving any infringement of the ordinary processes of development; and they account for the entire absence of corroborative facts in the past history of animals by what they call the "imperfection of the geological record." Now, while I admit that our knowledge of geology is still very incomplete, I assert that just where the direct sequence of geological deposits is needed for this evidence, we have it. The Jurassic beds, without a single modern scaly Fish, are in immediate contact with the Cretaceous beds, in which the Fishes of that kind are proportionately almost as numerous as they are now; and between these two sets of deposits there is not a trace of any transition or intermediate form to unite the reptilian Fishes of the Jurassic with the common Fishes of the Cretaceous times. Again, the Cretaceous beds in which the crowded banks of Rudistes, so singular and unique in form, first make their appearance, follow immediately upon those in which all the Bivalves are of an entirely different character. In short, the deposits of this year along any sea-coast or at the mouth of any of our rivers do not follow more directly upon those of last year than do these successive sets of beds of past ages follow upon each other. In making these statements, I do not forget the immense length of the geological periods; on the contrary, I fully accede to it, and believe that it is more likely to have been underrated than overstated. But let it be increased a thousand-fold, the fact remains, that these new types occur commonly at the dividing line where one period joins the next, just on the margin of both.

For years I have collected daily among some of these deposits, and I know the Sea-Urchins, Corals, Fishes, Crustacea, and Shells of those old shores as well as I know those of Nahant Beach, and there is nothing more striking to a naturalist than the sudden, abrupt changes of species in passing from one to another. In the second set of Cretaceous beds, the Neocomian, there is found a little Terebratula (a small Bivalve Shell) in immense quantities: they may actually be collected by the bushel. Pass to the Urgonian beds, resting directly upon the Neocomian, and there is not one to be found, and an entirely new species comes in. There is a peculiar Spatangus (Sea-Urchin) found throughout the whole series of beds in which this Terebratula occurs. At the same moment that you miss the Shell, the Sea-Urchin disappears also, and another takes its place. Now, admitting for a moment that the later can have grown out of the earlier forms, I maintain, that, if this be so, the change is immediate, sudden, without any gradual transitions, and is, therefore, wholly inconsistent with all our known physiological laws, as well as with the transmutation-theory.

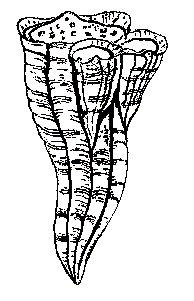

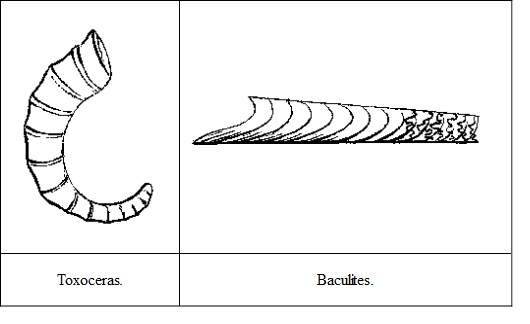

There is a very singular group of Ammonites in the Cretaceous epoch, which, were it not for the suddenness of its appearance, might seem rather to favor the development-theory, from its great variety of closely allied forms. We have traced the Chambered Shells from the straight, simple ones of the earliest epochs up to the intricate and closely coiled forms of the Jurassic epoch. In the so-called Portland stone, belonging to the upper set of Jurassic beds, there is only one type of Ammonite; but in the Cretaceous beds, immediately above it, there set in a number of different genera and distinct species, including the most fantastic and seemingly abnormal forms. It is as if the close coil by which these shells had been characterized during the Middle Age had been suddenly broken up and decomposed into an endless variety of outlines. Some of these new types still retain the coil, but the whorls are much less compact than before, as in the Crioceras; in others, the direction of the coil is so changed as to make a spiral, as in the Turrilites; or the shell starts with a coil, then proceeds in a straight line, and changes to a curve again at the other extremity, as in the Ancyloceras, or in the Scaphites, in which the first coil is somewhat closer than in the Ancyloceras; or the tendency to a coil is reduced to a single curve, so as to give the shell the outline of a horn, as in the Toxoceras; or the coil is entirely lost, and the shell reduced to its primitive straight form, as in the Baculites, which, except for their undulating partitions, might be mistaken for the Orthoceratites of the Silurian and Devonian epochs. I have presented here but a few species of these extraordinary Cretaceous Ammonites, and, strange to say, with this breaking-up of the type into a number of fantastic and often contorted shapes, it disappears. It is singular that forms so unusual and so contrary to the previous regularity of this group should accompany its last stage of existence, and seem to shadow forth by their strange contortions the final dissolution of their type. When I look upon a collection of these old shells, I can never divest myself of an impression that the contortions of a death-struggle have been made the pattern of living types, and with that the whole group has ended.

Now shall we infer that the compact, closely coiled Ammonites of the Jurassic deposits, while continuing their own kind, brought forth a variety of other kinds, and so distributed these new organic elements as to produce a large number of distinct genera and species? I confess that these ideas are so contrary to all I have learned from Nature in the course of a long life that I should be forced to renounce completely the results of my studies in Embryology and Palæontology before I could adopt these new views of the origin of species. And while the distinguished originator of this theory is entitled to our highest respect for his scientific researches, yet it should not be forgotten that the most conclusive evidence brought forward by him and his adherents is of a negative character, drawn from a science in which they do not pretend to have made personal investigations, that of Geology, while the proofs they offer us from their own departments of science, those of Zoölogy and Botany, are derived from observations, still very incomplete, upon domesticated animals and cultivated plants, which can never be made a test of the origin of wild species.11

In my next article I shall show the relation between the Cretaceous and Tertiary epochs, and see whether there is any reason to believe that the gigantic Mammalia of more modern times were derived from the Reptiles of the Secondary age.

THE WHITE-THROATED SPARROW

Hark! 't is our Northern Nightingale that singsIn far-off, leafy cloisters, dark and cool,Flinging his flute-notes bounding from the skies!Thou wild musician of the mountain-streams,Most tuneful minstrel of the forest-choirs,Bird of all grace and harmony of soul,Unseen, we hail thee for thy blissful voice!Up in yon tremulous mist where morning wakesIllimitable shadows from their dark abodes,Or in this woodland glade tumultuous grownWith all the murmurous language of the trees,No blither presence fills the vocal space.The wandering rivulets dancing through the grass,The gambols, low or loud, of insect-life,The cheerful call of cattle in the vales,Sweet natural sounds of the contented hours,—All seem less jubilant when thy song begins.Deep in the shade we lie and listen long;For human converse well may pause, and manLearn from such notes fresh hints of praise,That upward swelling from thy grateful tribeCircles the hills with melodies of joy.THE FLEUR-DE-LIS IN FLORIDA

[In the July number of this magazine is a sketch of the attempt of the Huguenots, under the auspices of Coligny, to found a colony at Port Royal. Two years later, an attempt was made to establish a Protestant community on the banks of the River St. John's, in Florida. The following paper embodies the substance of the letters and narratives of the actors in this striking episode of American history.]

CHAPTER I

On the 25th of June, 1564, a French squadron anchored a second time off the mouth of the River of May. There were three vessels, the smallest of sixty tons, the largest of one hundred and twenty, all crowded with men. René de Laudonnière held command. He was of a noble race of Poitou, attached to the House of Châtillon, of which Coligny was the head; pious, we are told, and an excellent marine officer. An engraving, purporting to be his likeness, shows us a slender figure, leaning against the mast, booted to the thigh, with slouched hat and plume, slashed doublet, and short cloak. His thin oval face, with curled moustache and close-trimmed beard, wears a thoughtful and somewhat pensive look, as if already shadowed by the destiny that awaited him.

The intervening year since Ribaut's voyage had been a dark and deadly year for France. From the peaceful solitude of the River of May, that voyager returned to a land reeking with slaughter. But the carnival of bigotry and hate had found a respite. The Peace of Amboise had been signed. The fierce monk choked down his venom; the soldier sheathed his sword; the assassin, his dagger; rival chiefs grasped hands, and masked their rancor under hollow smiles. The king and the queen-mother, helpless amid the storm of factions which threatened their destruction, smiled now on Condé, now on Guise,—gave ear to the Cardinal of Lorraine, or listened in secret to the emissaries of Theodore Beza. Coligny was again strong at Court. He used his opportunity, and solicited with success the means of renewing his enterprise of colonization. With pains and zeal, men were mustered for the work. In name, at least, they were all Huguenots; yet again, as before, the staple of the projected colony was unsound: soldiers, paid out of the royal treasury, hired artisans and tradesmen, joined with a swarm of volunteers from the young Huguenot noblesse, whose restless swords had rusted in their scabbards since the peace. The foundation-stone was left out. There were no tillers of the soil. Such, indeed, were rare among the Huguenots; for the dull peasants who guided the plough clung with blind tenacity to the ancient faith. Adventurous gentlemen, reckless soldiers, discontented tradesmen, all keen for novelty and heated with dreams of wealth,—these were they who would build for their country and their religion an empire beyond the sea.

With a few officers and twelve soldiers, Laudonnière landed where Ribaut had landed before him; and as their boat neared the shore, they saw an Indian chief who ran to meet them, whooping and clamoring welcome from afar. It was Satouriona, the savage potentate who ruled some thirty villages around the lower St. John's and northward along the coast. With him came two stalwart sons, and behind trooped a host of tribesmen arrayed in smoke-tanned deerskins stained with wild devices in gaudy colors. They crowded around the voyagers with beaming visages and yelps of gratulation. The royal Satouriona could not contain the exuberance of his joy, since in the person of the French commander he recognized the brother of the Sun, descended from the skies to aid him against his great rival, Outina.