полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 1, January 1916

All my beloved brethren beg their Christian love to you and all your dear brethren in the best bonds; and they also beg yourself and them will be pleased to remember the poor Ethiopian Baptists in their prayers, and be pleased also to accept the same from, Reverend and Dear Sir,

Your poor unworthy Brother, in the Lord Jesus Christ,

(Signed) T. N. S.

P.S. Brothers Baker, Gilbert, and others of the Africans, are going on wonderfully in the Lord's service, in the interior part of the country.

July 1, 1802.

–-Baptist Annual Register, 1801-1802, pages 974-975.

Letter to Dr. Rippon

Kingston, Jamaica, Oct. 9, 1802.

Rev. and Dear Sir,

I take the liberty to give you a further account of the spread of the Gospel among us.

On Saturday the 28th August last we laid our foundation stone for the building of the New Chapel; fifty-five feet in length, and twenty-nine and half feet in breath. The brethren assembled together at my house, and walked in procession to our place of worship, where a short discourse was delivered upon the subject, taken from Mat. XVI. 18. Upon this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of Hell shall not prevail against. As soon as divine service was over, we laid a stone in a pillar provided for that purpose, and on the stone was laid a small marble plate, and these words engraven thereon, St. John's Chapel was founded 28th August 1802, before a large and respectable congregation. The bricklayers have just raised the foundation above the surface of the earth. And as our Church consists chiefly of Slaves, and poor free people, we are not able to go on so fast as we could wish, for which reason we beg leave to call upon our Baptist friends in England, for their help and support of the Ethiopian Baptists, setting forward the glorious cause of our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, now in hand.

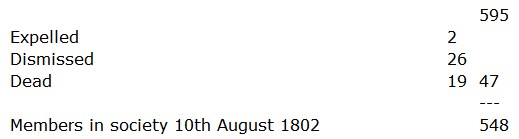

My last return of the Members in our Society on the 10th August last stood thus,

Since which, we have had sixty-two more added to the Church, almost all young people, and natives of different countries in Africa, which make 610 in Society.

About two months ago, I paid my first visit to a part of our Church held at Clinton Mount, Coffee Plantation, in the parish of Saint Andrew, about 16 miles distance from Kingston, in the High Mountains, where we have a Chapel and 254 brethren. And when I was at breakfast with the Overseer, he said to me, I have no need of a book-keeper (meaning an assistant), I make no use of a whip, for when I am at home my work goes on regular, and when I visit the field I have no fault to find, for every thing is conducted as it ought to be. I observed myself that the brethren were very industrious, they have a plenty of provisions in their ground, and a plenty of live stock, and they, one and all together, live in unity, brotherly love, and in the bonds of peace.

Last Lords Day, the 3rd October, was our quarterly baptism, when we walked from our place of Worship at noon, to the water, the distance of about a half mile, where I baptised eighteen professing believers, before a numerous and large congregation of spectators, which make in all 254 baptised by me since our commencement.

I am truly happy in acquainting you, that a greater spread of the gospel is taking place at the west end of the island.–A fortnight ago, the Rev. Brother Moses Baker visited me, he is a man of colour, a native of America, one of our baptist brothers and a member of our church, he is employed by a Mr. Winn, (a gentleman down in the country who possesses large and extensive properties in this island), to instruct his negroes in the principles of the Christian religion; and Mr. Vaughan has employed him for that purpose, and both these gentlemen allow him a compensation. Mr. Winn finds him in house room, lands, &c., &c., and by his instructing those slaves at Mr. Vaughan's properties, several miles from Mr. Winn's estate, a number of slaves belonging to different properties (no less than 20 sugar estates in number) are become converted souls.–Mr. Baker's errand to me was, that he wanted a person to assist him, he being sent for by a Mr. Hilton, a gentleman down in the parish of Westmoreland (50 miles distance from Mr. Baker's dwelling place), to instruct his and another gentlemen's slaves, on two large sugar estates, into the word of God, producing to me at the same time the letters and invitations he received. I gave him brother George Vineyard, one our exhorters, and old experienced professor (who has been called by grace upwards of eighteen years) to assist him; he also is a native of America, and this gentleman Mr. Hilton, has provided a House, and maintainance, a salary, and land for him to cultivate for his benefit upon his own estate, and brother Baker declared to me, that he has in the church there, fourteen hundred justified believers, and about three thousand followers, many under conviction for sin. The distance brother Baker is at from me is 136 miles, he has undergone a great deal of persecution and severe trials for the preaching of the gospel, but our Lord has delivered him safe out of all–Myself and brethren were at Mr. Liele's Chapel a few weeks ago at the funeral of one of his elders, he is well, and we were friendly together. All our brethren unite with me in giving their most Christian love to you, and all the dear beloved brethren in your church in the best bonds, and beg, both yourself and them, will be pleased to remember the Ethiopian Baptists in their prayers, and I remain dear Sir, and brother,

Your poor unworthy brother, in the Lord Jesus Christ,

(Signed) Thomas Nicholas Swigle.

P.S. These sugar estates, in the parish where Brother Baker resides, are very large and extensive; and they have three to four hundred slaves on each property.

–-Baptist Annual Register, 1800-1802, pages 1144-1146.

Book Reviews

The Haitian Revolution, 1791 to 1804. By T. G. Steward. Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, 1915. 292 pages. $1.25.

In the days when the internal dissensions of Haiti are again thrusting her into the limelight such a book as this of Mr. Steward assumes a peculiar importance. It combines the unusual advantage of being both very readable and at the same time historically dependable. At the outset the author gives a brief sketch of the early settlement of Haiti, followed by a short account of her development along commercial and racial lines up to the Revolution of 1791. The story of this upheaval, of course, forms the basis of the book and is indissolubly connected with the story of Toussaint L'Overture. To most Americans this hero is known only as the subject of Wendell Phillips's stirring eulogy. As delineated by Mr. Steward, he becomes a more human creature, who performs exploits, that are nothing short of marvelous. Other men who have seemed to many of us merely names–Rigaud, Le Clerc, Desalines, and the like–are also fully discussed.

Although most of the book is naturally concerned with the revolutionary period, the author brings his account up to date by giving a very brief resumé of the history of Haiti from 1804 to the present time. This history is marked by the frequent occurrence of assassinations and revolutions, but the reader will not allow himself to be affected by disgust or prejudice at these facts particularly when he is reminded, as Mr. Steward says, "that the political history of Haiti does not differ greatly from that of the majority of South American Republics, nor does it differ widely even from that of France."

The book lacks a topical index, somewhat to its own disadvantage, but it contains a map of Haiti, a rather confusing appendix, a list of the Presidents of Haiti from 1804 to 1906 and a list of the names and works of the more noted Haitian authors. The author does not give a complete bibliography. He simply mentions in the beginning the names of a few authorities consulted.

J. R. Fauset.The Negro in American History. By John W. Cromwell. The American Negro Academy, Washington, D.C., 1914. 284 pages. $1.25 net.

In John W. Cromwell's book, "The Negro in American History," we have what is a very important work. The book is mainly biographical and topical. Some of the topics discussed are: "The Slave Code"; "Slave Insurrections"; "The Abolition of the Slave Trade"; "The Early Convention Movement"; "The Failure of Reconstruction"; "The Negro as a Soldier"; and "The Negro Church." These topics are independent of the chapters which are more particularly chronological in treatment.

In the appendices we have several topics succinctly treated. Among these are: "The Underground Railroad," "The Freedmen's Bureau," and, most important and wholly new, a list of soldiers of color who have received Congressional Medals of Honor, and the reasons for the bestowal.

The biographical sketches cover some twenty persons. Much of the information in these sketches is not new, as would be expected regarding such well-known persons as Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. On the other hand, Mr. Cromwell has given us very valuable sketches of other important persons of whom much less is generally known. Among these are Sojourner Truth, Edward Wilmot Blyden, and Henry O. Tanner.

The book does not pretend to be the last word concerning the various topics and persons discussed. Indeed, some of the topics have had fuller treatment by the author in pamphlets and lectures. It is to be regretted that the author did not feel justified in giving a more extensive treatment, as the great store of his information would easily have permitted him to do.

The book is exceptionally well illustrated, but it lacks information regarding some of the illustrations. Not only are the readers of a book entitled to know the source of the illustrations but in the case of copies of paintings, and other works of art, the original artist is as much entitled to credit as an author whose work is quoted or appropriated to one's use.

Negro Culture In West Africa. By George W. Ellis, K.C., F.R.G.S. The Neale Publishing Co., New York, 1914. 290 pages. $2.00 net.

This study by Mr. Ellis of the culture of West Africa as represented by the Vai tribe, is valuable both as a document and as a scientific treatment of an important phase of the color problem. As a document it is an additional and a convincing piece of evidence of the ability of the Negro to treat scientifically so intricate a problem as the rise, development, and meaning of the social institutions of a people. Easy, yet forceful in style; well documented with footnotes and cross references; amply illustrated with twenty-seven real representations of tools, weapons, musical instruments and other pieces of handwork; containing, incidentally, a good bibliography of the subject; and finally, with its conclusions condensed in the last four pages, it is a book excellent in plan and in execution. The map, however, which has been selected for the book is overcrowded and, therefore, practically useless.

As a scientific study, its value is suggested by the topics emphasized, viz., "Climate," "Institutions," "Foreign Influence," "Proverbs," "Folklore," and "Writing System." Referring to the climate the author says: "In West Africa the body loses its strength, the memory its retentiveness, and the will its energy. These are the effects observed upon persons remaining in West Africa only for a short time, and they form a part of the experience of almost every person who has lived on the West Coast. White persons,–with beautiful skin, clear and soft, and with rosy cheeks,–after they have been in West Africa for a while become dark and tawny like the inhabitants of Southern Spain and Italy. If we can detect these effects of the West African climate in only a short time upon persons who come to the West Coast, what must have been the effect of such a climate upon the Negroes who for centuries have been exposed to its hardships?"

The moral life of the Vais appears to be the product of their social institutions and their severe environment. These institutions grow out of the necessities of government for the tribe under circumstances which suggest and enforce their superstitions and beliefs. This is not so with respect to education. It seems that the influence of the "Greegree Bush" (a school system) is now considerably weakened by the Liberian institutions on the one hand, the Mohammedan faith and customs on the other. So that now this institution falls short of achieving its aims, and putting its principles into practice.

The study as a whole gives evidence of the author's eight years of travel and research, and can be read with profit by all friends of mankind.

Walter Dyson.The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. By C. G. Woodson, Ph.D. G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1915. 460 pages. $2.00 net.

The very title of Dr. Woodson's book causes one who is interested in the race history to ask questions and think. There are comparatively few people who know anything about the efforts made to educate the Negro prior to 1861. Consequently, from the first page of the book to the last, the reader is continually acquiring facts concerning this most interesting and important phase of the Colored-American's history of which he has never heard before, and some of which seem too wonderful to be true. But it is not possible to doubt anything which is found in Dr. Woodson's book. One knows that every statement he reads concerning the education of the Negro prior to 1861 is true, for the author has taken pains to substantiate every fact that he presents.

It is difficult to imagine any phase of race history more fascinating and more thrilling than an account of the desperate and prolonged struggle between the forces which made for the mental and spiritual enlightenment of the slave and those which opposed these humane and Christian efforts with all the bitterness and strength at their command. The reasons assigned by those who favored the education of the slaves and the methods suggested together with the arguments used by those who were opposed to it and the laws enacted to prevent it furnish an illuminating study in human nature.

One is surprised to find that very early in the history of the colonies there were scholars and statesmen who did not hesitate to declare their belief in the intellectual possibilities of the Negro. These men agreed with George Buchanan that the Negro had talent for the fine arts and under favorable circumstances could achieve something worth while in literature, mathematics and philosophy. The high estimate placed upon the innate ability of the Negro may be attributed to the fact that early in the history of the country there was a goodly number of slaves who had managed to attain a certain intellectual proficiency in spite of the difficulties which had to be overcome. By 1791 a colored minister had so distinguished himself that he was called to the pastorate of the First Baptist Church (white) of Portsmouth, Va. Benjamin Banneker's proficiency in mathematics enabled him to make the first clock manufactured in the United States. As the author himself says, "the instances of Negroes struggling to obtain an education read like the beautiful romances of a people in an heroic age."

Indeed the reaction which developed against allowing the slaves to pick up the few fragments of knowledge which they had been able to secure was due to some extent to the enthusiasm and eagerness with which they availed themselves of the opportunities afforded them and the salutary effect which the enlightenment had on their character. The account of the establishment of schools and churches for slaves who were transplanted to free soil is one of the most interesting chapters in the book. The struggle for the higher education shows that tremendous obstacles had been removed, before the race was allowed to secure the opportunity which it so earnestly desired. In the chapter on vocational training the effort made by colored people themselves to secure economic equality, and the determined opposition to it manifested by white mechanics are clearly and strongly set forth. In the appendix of the book one finds a number of interesting and valuable treatises, while the bibliography is of great assistance to any student of race history.

In addition to the fund of information which is secured by reading Dr. Woodson's book, a perusal of it can not help but increase one's respect for a race which under the most disheartening and discouraging circumstances strove so heroically and persistently to cultivate its mind and allowed nothing to turn it aside and conquer its will.

"The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861" is a work of profound historical research, full of interesting data on a most important phase of race life which has hitherto remained unexplored and neglected.

Mary Church Terrell.Notes

In the death of Booker T. Washington the field of history lost one of its greatest figures. He will be remembered mainly as an educational reformer, a man of vision, who had the will power to make his dreams come true. In the field of history, however, he accomplished sufficient to make his name immortal. His "Up from Slavery" is a long chapter of the story of a rising race; his "Frederick Douglass" is the interpretation of the life of a distinguished leader by a great citizen; and his "Story of the Negro" is one of the first successful efforts to give the Negro a larger place in history.

Doubleday, Page and Company will in the near future publish an extensive biography of Booker T. Washington.

During the Inauguration Week of Fisk University a number of Negro scholars held a conference to consider making a systematic study of Negro life. A committee was appointed to arrange for a larger meeting.

Dr. C. G. Woodson is now writing a volume to be entitled "The Negro in the Northwest Territory"

The Neale Publishing Company has brought out "The Political History of Slavery in the United States" by J. Z. George.

"Lincoln and Episodes of the Civil War" by W. E. Doster, appears among the publications of the Putnams.

"Black and White in the South" is the title of a volume from the pen of M. S. Evans, appearing with the imprint of Longmans, Green and Company.

T. Fisher Unwin has brought out "The Savage Man in Central Africa" by A. L. Cureau.

"Reconstruction in Georgia, Social, Political, 1865-1872" by C. Mildred Thompson, appears as a comprehensive volume in the Columbia University Studies in History, Economics, and Public Law.

The Journal of Negro History

Vol. I., No. 2 April, 1916

PUBLISHED QUARTERLY

The Historic Background of the Negro Physician

In a homogeneous society where there is no racial cleavage, only the selected members of the most favored class occupy the professional stations. The element representing the social status of the Negro would, therefore, furnish few members of the coveted callings. The element of race, however, complicates every feature of the social equation. In India we are told that the population is divided horizontally by caste and vertically by religion; but in America the race spirit serves both as horizontal and vertical separations. The Negro is segregated and shut in to himself in all social and semi-social relations of life. This isolation necessitates separate ministrative agencies from the lowest to the highest rounds of the ladder of service. During the days of slavery the interests of the master demanded that he should direct the general social and moral life of the slave, and should provide especially for his physical well-being. The sudden severance of this tie left the Negro wholly without intimate guidance and direction. The ignorant must be enlightened, the sick must be healed, and the poor must have the gospel preached to them. The situation and circumstances under which the race found itself demanded that its professional class, for the most part, should be men of their own blood and sympathies. The needed service could not be effectively performed by those who assumed and asserted racial arrogance, and bestowed their professional service as cold crumbs that fell from the master's table. The professional class who are to uplift and direct the lowly must not say, "So far shalt thou come, but not any farther," but rather, "Where I am, there ye shall be also."

There is no more pathetic chapter in the history of human struggle than the emergence of the smothered ambition of this race to meet the social exigencies involved in the professional needs of the masses. In an instant, in the twinkling of an eye, the plowhand was transformed into a priest, the barber into a bishop, the housemaid into a schoolmistress, the day-laborer into a lawyer, and the porter into a physician. These high places of intellectual and professional authority, into which they found themselves thrust by stress of social necessity, had to be operated with at least some semblance of conformity to the standards which had been established by the European through the traditions of the ages. The higher place in society occupied by the choicest members of the white race, and that too after long years of arduous preparation, had to be assumed by black men without personal or formal fitness. The stronger and more aggressive natures pushed themselves into these higher callings by sheer force of untutored energy and uncontrolled ambition.

An accurate study of the healing art as practiced by Negroes in Africa as well as its continuance after transplantation in America would form an investigation of great historical interest. This, however, is not the purpose of this paper. It is sufficient to note the fact that witchcraft and the control of disease through roots, herbs, charms and conjuration are universally practiced on the continent of Africa. Indeed, the medicine man has a standing and influence that is sometimes superior to that of kings and queens. The natives of Africa have discovered their own materia medica by actual practice and experience with the medicinal value of minerals and plants. It must be borne in mind that any pharmacopeia must rest upon the basis of practical experiment and experience. The science of medicine was developed by man in his groping to relieve pain and to curb disease, and was not handed down ready made from the skies. In this groping, the African, like the rest of the children of men, has been feeling after the right remedies, if haply he might find them.

It was inevitable that the prevailing practice of conjuration in Africa should be found among Negroes after they had been transferred to the new continent. The conjure man was well known in every slave community. He generally turned his art, however, to malevolent rather than benevolent uses; but this was not always the case. Not infrequently these medicine men gained such wide celebrity among their own race as to attract the attention of the whites. As early as 1792 a Negro by the name of Cesar98 had gained such distinction for his curative knowledge of roots and herbs that the Assembly of South Carolina purchased his freedom and gave him an annuity of one hundred pounds.

That slaves not infrequently held high rank among their own race as professional men may be seen from the advertisements of colonial days. A runaway Negro named Simon was in 1740 advertised in The Pennsylvania Gazette99 as being able to "bleed and draw teeth" and "pretending to be a great doctor among his people." Referring in 1797 to a fugitive slave of Charleston, South Carolina, The City Gazette and Daily Advertiser100 said: "He passes for a Doctor among people of his color and it is supposed practices in that capacity about town." The contact of such practitioners with the white race was due to the fact that the profession of the barber was at one time united with that of the physician. The practice of phlebotomy was considered an essential part of the doctor's work. As the Negro early became a barber and the profession was united with that of the physician, it is natural to suppose that he too would assume the latter function. That phlebotomy was considered an essential part of the practice of the medicine is seen from the fact that it was practiced upon George Washington in his last illness. An instance of this sort of professional development among the Negroes appears in the case of the barber, Joseph Ferguson. Prior to 1861 he lived in Richmond, Virginia, uniting the three occupations of leecher, cupper, and barber. This led to his taking up the study of medicine in Michigan, where he graduated and practiced for many years.