полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 1, January 1916

The leaders of the Revolution, therefore, quickly receded from their radical position of excluding Negroes from the army. Informed that the free Negroes who had served in the ranks in New England were sorely displeased at their exclusion from the service, and fearing that they might join the enemy, Washington departed, late in 1775, from the established policy of the staff and gave the recruiting officers leave to accept such Negroes, promising to lay the matter before the Continental Congress, which he did not doubt would approve it.130 Upon the receipt of this communication the matter was referred to a committee composed of Wythe, Adams and Wilson, who recommended that free Negroes who had served faithfully in the army at Cambridge might be reenlisted but no others.131 In taking action on such communications thereafter the Continental Congress followed the policy of leaving the matter to the various States, which were then jealously mindful of their rights.

Sane leaders generally approved the enlistment of black troops. General Thomas thought so well of the proposition that he wrote John Adams in 1775, expressing his surprise that any prejudice against it should exist.132 Samuel Hopkins said in 1776 that something should be speedily done with respect to the slaves to prevent their turning against the Americans. He was of the opinion that the way to counteract the tendency of the Negroes to join the British was not to restrain them by force and severity but by public acts to set the slaves free and encourage them to labor and take arms in defense of the American cause.133 Interested in favor of the Negroes both by "the dictates of humanity and true policy," Hamilton urged that slaves be given their freedom with the swords to secure their fidelity, animate their courage, and influence those remaining in bondage by opening a door to their emancipation.134 General Greene emphatically urged that blacks be armed, believing that they would make good soldiers.135 Thinking that the slaves might be put to a much better use than being given as a bounty to induce white men to enlist, James Madison suggested that the slaves be liberated and armed.136 "It would certainly be consonant to the principles of liberty," said he, "which ought never to be lost sight of in a contest for liberty." John Laurens, of South Carolina, was among the first to see the wisdom of this plan, directed the attention of his coworkers to it, and when authorized by the Continental Congress, proceeded to his native State, wishing that he had the persuasive power of a Demosthenes to make his fellow citizens accept this proposition.137 In 1779 Laurens said: "I would advance those who are unjustly deprived of the rights of mankind to a state which would be a proper gradation between abject slavery and perfect liberty, and besides I am persuaded that if I could obtain authority for the purpose, I would have a corps of such men trained, uniformly clad, equipped and ready in every respect to act at the opening of the next campaign."

All of the colonies thereafter tended to look more favorably upon the enlistment of colored troops. Free Negroes enlisted in Virginia and so many slaves deserted their masters for the army that the State enacted in 1777 a law providing that no Negro should be enlisted unless he had a certificate of freedom.138 That commonwealth, however, soon took another step toward greater recognition of the rights of the Negroes who desired to be free to help maintain the honor of the State. With the promise of freedom for military service many slaves were sent to the army as substitutes for freemen. The effort of inhuman masters to force such Negroes back into slavery at the close of their service at the front actuated the liberal legislators of that commonwealth to pass the Act of Emancipation, proclaiming freedom to all Negroes who had thus enlisted and served their term faithfully, and empowered them to sue in forma pauperis, should they thereafter be unlawfully held in bondage.139

In the course of time there arose an urgent need for the Negro in the army. The army reached the point when almost all sorts of soldiers were acceptable. In 1778 General Varnum induced General Washington to send certain officers from Valley Forge to Rhode Island to enlist a battalion of Negroes to fill the depleted ranks of that State.140 Setting forth in the preamble that "history affords us frequent precedents of the wisest, freest and bravest nations having liberated their slaves and enlisted them as soldiers to fight in defense of their country," the Rhode Island Assembly resolved to raise a regiment of slaves, who were to be freed upon their enlistment, their owners to be paid by the State according to the valuation of a committee. Further light was thrown upon this action in the statement of Governor Cooke, who in reporting the action of the Assembly to Washington boasted that liberty was given to every effective slave to don the uniform and that upon his passing muster he became absolutely free and entitled to all the wages, bounties and encouragements given to any other soldier.141

The State of New Hampshire enlisted Negroes and gave to those who served three years the same bounty offered others. This bounty was turned over to their masters as the price of the slaves in return for which their owners issued bills of sale and certificates of freedom.142 In this way slavery practically passed out in New Hampshire. This affair did not proceed so smoothly as this in Massachusetts. In 1778 that legislature had a committee report in favor of raising a regiment of mulattoes and Negroes. This action was taken as a result upon receiving an urgent letter from Thomas Kench, a member of an artillery regiment serving on Castle Island. Kench referred to the fact that there were divers of Negroes in the battalions mixed with white men, but he thought that the blacks would have a better esprit de corps should they be organized in companies by themselves. But the feeling that slaves should not fight the battles of freemen and a confusion of the question of enlistment with that of emancipation for which Massachusetts was not then prepared,143 led to a heated debate in the Massachusetts Council and finally to blows in the coffee houses in lower Boston. In such an excited state of affairs no further action was taken. Finding recruiting difficult it is said that Connecticut undertook to raise a colored regiment144 and in 1781 New York, offering the usual land bounty which would go to the masters to purchase the slaves, promised freedom to all slaves who would enlist for the time of three years.145 Maryland provided in 1780 that each unit of £16,000 of property should furnish one recruit who might be either a freeman or a slave, and in 1781 resolved to raise 750 Negroes to be incorporated with the other troops.146

Farther South the enlistment of Negroes had met with obstacles. The best provision the Southern legislatures had been able to make was to provide in addition to the allotment of money and land that a person offering to fight for the country should have "one sound Negro"147 or a "healthy sound Negro"148 as the laws provided in Virginia and South Carolina respectively. Threatened with invasion in 1779, however, the Southern States were finally compelled to consider this matter more seriously.149 The Continental Army had been called upon to cope with the situation but had no force available for service in those parts. The three battalions of North Carolina troops, then on duty in the South, consisted of drafts from the militia for nine months, which would expire before the end of the campaign. What were they to do then when this militia, which could not be uniformly kept up, should grow impatient with the service? Writing from the headquarters of the army at this time, Alexander Hamilton in discussing the advisability of this plan doubtless voiced the sentiment of the staff. He thought that Colonel Laurens's plan for raising three or four battalions of emancipated Negroes was the most rational one that could be adopted in that state of Southern affairs. Hamilton foresaw the opposition from prejudice and self-interest, but insisted that if the Americans did not make such a use of the Negroes, the British would.

The movement received further impetus when special envoys from South Carolina headed by Huger appeared before the Continental Congress on March 29, 1779, to impress upon that body the necessity of doing something to relieve the Southern colonies. South Carolina, they reported, was suffering from an exposed condition in that the number of slaves being larger than that of the whites, she was unable to effect anything for its defense with the natives, because of the large number necessary to remain at home to prevent insurrections among the Negroes and their desertion to the enemy. These representatives, therefore, suggested that there might be raised among the Negroes in that State a force "which would not only be formidable to the enemy from their numbers and the discipline of which they would readily admit but would also lessen the danger from revolts and desertions by detaching the most vigorous and enterprising from among the Negroes." At the same time the Committee expressed the opinion that a matter of such vital interest to the two States concerned should be referred to their legislative bodies to judge as to the expediency of taking this step, and that if these commonwealths found it satisfactory that the United States should defray the expenses.

Congress passed a resolution complying with these recommendations.150 Laurens, the father of the movement, was made a lieutenant-colonel and he went immediately home to urge upon South Carolina the expediency of adopting this plan. There Laurens met determined opposition from the majority of the aristocrats who set themselves against "a measure of so threatening aspect and so offensive to that republican pride, which disdains to commit the defence of the country to servile bands or share with a color to which the idea of inferiority is inseparably connected, the profession of arms, and that approximation of condition which must exist between the regular soldier and the militiaman." It was to no purpose too that Laurens renewed his efforts at a later period. He mustered all of his energy to impress upon the Legislature the need of taking this action but finally found himself outvoted, having only reason on his side and "being opposed by a triple-headed monster that shed the baneful influence of avarice, prejudice, and pusillanimity in all our assemblies." "It was some consolation to me, however," said he, "to find that philosophy and truth had made some little progress since my last effort, as I obtained twice as many suffrages as before."

Hearing of the outcome, Washington wrote him that he was not at all astonished at it, as that spirit of freedom, which at the commencement of the Revolution would have sacrificed everything to the attainment of this object, had long since subsided, and every selfish passion had taken its place. "It is not the public but the private interest," said he, "which influences the generality of mankind, nor can Americans any longer boast an exception. Under these circumstances it would have been rather surprising if you had succeeded."151 It is difficult, however, to determine exactly what Washington's attitude was. Two days after Hamilton wrote Jay about raising colored troops in South Carolina, the elder Laurens wrote Washington: "Had we arms for three thousand such black men as I could select in Carolina, I should have no doubt of success in driving the British out of Georgia, and subduing East Florida before the end of July." To this Washington answered: "The policy of our arming slaves is in my opinion a moot point, unless the enemy set the example. For, should we begin to form Battalions of them, I have not the smallest doubt, if the war is to be prosecuted, of their following us in it, and justifying the measure upon our own ground. The contest then must be who can arm fastest, and where are our arms? Besides I am not clear that a discrimination will not render slavery more irksome to those who remain in it. Most of the good and evil things in this life are judged by comparison; and I fear a comparison in this case will be productive of much discontent in those, who are held in servitude. But, as this is a subject that has never employed much of my thoughts, these are no more than the first crude Ideas that have struck me upon ye occasion."152

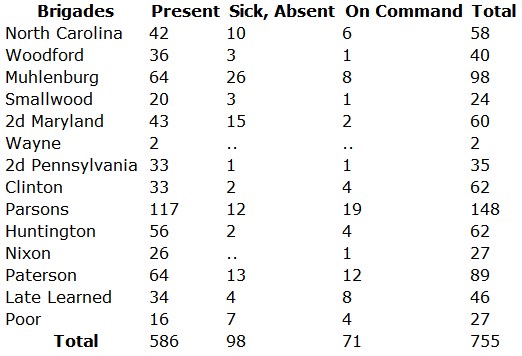

What then resulted from the agitation and discussion? The reader naturally wants to know how many Negroes were actually engaged in the Continental Army. Here we find ourselves at sea. We have any amount of evidence that the number of Negroes engaged became considerable, but exact figures are for several reasons lacking. In the first place, free Negroes rarely served in separate battalions. They marched side by side with the white soldier, and in most cases, according to the War Department, even after making an extended research as to the names, organizations, and numbers, the results would be that little can be obtained from the records to show exactly what soldiers were white and what were colored.153 Moreover the first official efforts to keep the Negroes out of the army must not be regarded as having stopped such enlistments. As there was not any formal system of recruiting, black men continued to enlist "under various laws and sometimes under no law, and in defiance of law." The records of every one of the original thirteen States show that each had colored troops. A Hessian officer observed in 1777 that "the Negro can take the field instead of his master; and, therefore, no regiment is to be seen in which there are not negroes in abundance, and among them there are able-bodied, strong and brave fellows."154 "Here too," said he, "there are many families of free negroes who live in good homes, have property and live just like the rest of the inhabitants." In 1777 Alexander Scammell, Adjutant-General, made the following report as to the number and placement of the Negroes in the Continental Army:

Return of Negroes in the Army, 24th August, 1778

Alexander Scammell, Adjutant-General.155

But this report neither included the Negro soldiers enlisted in several other States nor those that joined the army later. Other records show that Negroes served in as many as 18 brigades.

Some idea of the number of Negroes engaged may be obtained from the context of documents mentioning the action taken by States. Rhode Island we have observed undertook to raise a regiment of slaves. Governor Cooke said that the slaves found there were not many but that it was generally thought that 300 or more would enlist. Four companies of emancipated slaves were finally formed in that State at a cost of £10,437 7s 7d.156 Most of the 629 slaves then found in New Hampshire availed themselves of the opportunity to gain their freedom by enlistment as did many of the 15,000 slaves in New York. Connecticut had free Negroes in its regiments and formed also a regiment of colored soldiers assigned first to Meigs' and afterward to Butler's command. Maryland resolved in 1781 to raise 750 Negroes to be incorporated with the other troops. Massachusetts thought of forming a separate battalion of Negroes and Indians but had no separate Negro regiment, the Negroes having been admitted into the other battalions, after 1778, to the extent that there were colored troops from 72 towns in that State. In view of these numerous facts it is safe to conclude that there were at least 4,000 Negro soldiers scattered throughout the Continental Army.

As to the value of the services rendered by the colored troops we have only one witness to the contrary. This was Sidney S. Rider. He tried to ridicule the black troops engaged in the Battle of Rhode Island and contended that only a few of them took part in the contest.157 On the other hand we have two distinguished witnesses in their favor. The Marquis de Chastellux said that "at the passage to the ferry I met a detachment of the Rhode Island regiment, the same corps we had with us the last summer, but they have since been recruited and clothed. The greatest part of them are Negroes or Mulattoes; but they are strong, robust men, and those I have seen had a very good appearance."158 Speaking of the behavior of troops, among whom Negroes under General Greene fought on this occasion, Lafayette said the following day, that the enemy repeated the attempt three times (tried to carry his position), and were as often repulsed with great bravery.159 One hundred and forty-four of the soldiers thus engaged to roll back the lines of the enemy were, according to the Revolutionary records, Negroes.160 Doctor Harris, a Revolutionary soldier, who took part in the Battle of Rhode Island, said of these Negroes: "Had they been unfaithful or even given away before the enemy all would have been lost. Three times in succession they were attacked with more desperate valor and fury by well disciplined and veteran troops, and three times did they successfully repel the assault and thus preserved our army from capture."161 A detachment of these troops sacrificed themselves to the last man in defending Colonel Greene in 1781 when he was attacked at Point Bridge, New York. A Negro slave of South Carolina rendered Governor Rutledge such valuable service that by a special act of the legislature in 1783 his wife and children were enfranchised.162

The valor of the Negro soldiers of the American Revolution has been highly praised by statesmen and historians. Writing to John Adams, a member of the Continental Congress, in 1775, to express his surprise at the prejudice against the colored troops in the South, General Thomas said: "We have some Negroes but I look on them in general equally serviceable with other men for fatigue, and in action many of them had proved themselves brave." Graydon in speaking of the Negro troops he saw in Glover's regiment at Marblehead, Massachusetts, said: "But even in this regiment (a fine one) there were a number of Negroes."163 Referring to the battle of Monmouth, Bancroft said: "Nor may history omit to record that, of the 'revolutionary patriots' who on that day perilled life for their country, more than seven hundred black men fought side by side with the white."164 According to Lecky, "the Negroes proved excellent soldiers: in a hard fought battle that secured the retreat of Sullivan they three times drove back a large body of Hessians."165 We need no better evidence of the effective service of the Negro soldier than the manner in which the best people of Georgia honored Austin Dabney,166 a mulatto boy who took a conspicuous part in many skirmishes with the British and Tories in Georgia. While fighting under Colonel Elijah Clarke he was severely wounded by a bullet which in passing through his thigh made him a cripple for life. He received a pension from the United States and was by an act of the legislature of Georgia given a tract of land. He improved his opportunities, acquired other property, lived on terms of equality with some of his white neighbors, had the respect and confidence of high officials, and died mourned by all.

W. B. HartgroveFreedom and Slavery in Appalachian America

To understand the problem of harmonizing freedom and slavery in Appalachian America we must keep in mind two different stocks coming in some cases from the same mother country and subject here to the same government. Why they differed so widely was due to their peculiar ideals formed prior to their emigration from Europe and to their environment in the New World. To the Tidewater came a class whose character and purposes, although not altogether alike, easily enabled them to develop into an aristocratic class. All of them were trying to lighten the burdens of life. In this section favored with fertile soil, mild climate, navigable streams and good harbors facilitating direct trade with Europe, the conservative, easy-going, wealth-seeking, exploiting adventurers finally fell back on the institution of slavery which furnished the basis for a large plantation system of seeming principalities. In the course of time too there arose in the few towns of the coast a number of prosperous business men whose bearing was equally as aristocratic as that of the masters of plantations.167 These elements constituted the rustic nobility which lorded it over the unfortunate settlers whom the plantation system forced to go into the interior to take up land. Eliminating thus an enterprising middle class, the colonists tended to become more aristocratic near the shore.

In this congenial atmosphere the eastern people were content to dwell. the East had the West in mind and said much about its inexhaustible resources, but with the exception of obtaining there grants of land nothing definite toward the conquest of this section was done because of the handicap of slavery which precluded the possibility of a rapid expansion of the plantation group in the slave States. Separated thus by high ranges of mountains which prevented the unification of the interests of the sections, the West was left for conquest by a hardy race of European dissenters who were capable of a more rapid growth.168 these were the Germans and Scotch-Irish with a sprinkling of Huguenots, Quakers and poor whites who had served their time as indentured servants in the east.169 The unsettled condition of Europe during its devastating wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries caused many of foreign stocks to seek homes in America where they hoped to realize political liberty and religious freedom. Many of these Germans first settled in the mountainous district of Pennsylvania and Maryland and then migrated later to the lower part of the Shenandoah Valley, while the Scotch-Irish took possession of the upper part of that section. Thereafter the Shenandoah Valley became a thoroughfare for a continuous movement of these immigrants toward the south into the uplands and mountains of the Carolinas, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee.170

Among the Germans were Mennonites, Lutherans, and Moravians, all of whom believed in individual freedom, the divine right of secular power, and personal responsibility.171 The strongest stock among these immigrants, however, were the Scotch-Irish, "a God-fearing, Sabbath-keeping, covenant-adhering, liberty-loving, and tyrant-hating race," which had formed its ideals under the influence of philosophy of John Calvin, John Knox, Andrew Melville, and George Buchanan. By these thinkers they had been taught to emphasize equality, freedom of conscience, and political liberty. These stocks differed somewhat from each other, but they were equally attached to practical religion, homely virtues, and democratic institutions.172 Being a kind and beneficent class with a tenacity for the habits and customs of their fathers, they proved to be a valuable contribution to the American stock. As they had no riches every man was to be just what he could make himself. Equality and brotherly love became their dominant traits. Common feeling and similarity of ideals made them one people whose chief characteristic was individualism.173 Differing thus so widely from the easterners they were regarded by the aristocrats as "Men of new blood" and "Wild Irish," who formed a barrier over which "none ventured to leap and would venture to settle among."174 No aristocrat figuring conspicuously in the society of the East, where slavery made men socially unequal, could feel comfortable on the frontier, where freedom from competition with such labor prevented the development of caste.

The natural endowment of the West was so different from that of the East that the former did not attract the people who settled in the Tidewater. The mountaineers were in the midst of natural meadows, steep hills, narrow valleys of hilly soil, and inexhaustible forests. In the East tobacco and corn were the staple commodities. Cattle and hog raising became profitable west of the mountains, while various other employments which did not require so much vacant land were more popular near the sea. Besides, when the dwellers near the coast sought the cheap labor which the slave furnished the mountaineers encouraged the influx of freemen. It is not strange then that we have no record of an early flourishing slave plantation beyond the mountains. Kercheval gives an account of a settlement by slaves and overseers on the large Carter grant situated on the west side of the Shenandoah, but it seems that the settlement did not prosper as such, for it soon passed into the hands of the Burwells and the Pages.175