Полная версия

Chasing the Moon

Clarke sat up and listened to Joe Martin with astonishment. A politician was on national TV giving a speech that contained passages that could have been written by Clarke himself. “I didn’t expect the Republican Party to take official cognizance of the topics the science-fiction writers love to mull over,” he recalled later. He listened as Martin talked of smart “electronic computing machines” and wrist radios utilizing “a new invention no bigger than a postage stamp, called the transistor.” He was delighted. “After that, nothing could drag me away from the convention.”

This was only the second trip Clarke had taken outside of the United Kingdom, and as he traveled the United States, others aspects of 1950s America caught his attention. At the invitation of Ian Macaulay, a fanzine editor whom he had met at a science-fiction convention, Clarke traveled to Atlanta, Georgia. At that moment Macaulay was active in the fight for civil rights, organizing to end segregation in schools and public transportation and working to increase African American voter registration. Macaulay’s activism prompted some lengthy late-night discussions during which Clarke learned more about America’s long history of racial inequity.

Prior to coming to the United States, Clarke had never met any black people. He stayed with Macaulay again in Atlanta the following year, and during his return visit he was at work on the final pages of his novel Childhood’s End. In the book’s conclusion, an adventurous scientist named Jan Rodricks is selected by representatives of an advanced extraterrestrial civilization to witness the transformation of the human race into a higher form of life: a collective cosmic entity. Clarke’s decision to make Rodricks—his fictional representative of all mankind and “the last person on Earth”—an astronomer of black African descent was a bold and politically provocative choice for 1953.

Since reading a short story about a sympathetic alien in a 1934 issue of Wonder Stories, Clarke had been fascinated by science fiction’s potential to evoke empathy for alien characters and convey to readers the viewpoint and values of those from other cultures. During its formative decades, the genre’s predominantly male readership was hungry for escape from the mainstream culture and curious about emerging technologies and new ideas. Many science-fiction readers were intelligent yet socially marginalized in some way due to a variety of reasons, such as ethnicity, sexuality, religion, or race. Plus, conventional society’s habit of ostracizing and calling those with an interest in technical or intellectual subjects “nerds” or “eggheads” was familiar to a sizable segment of the genre’s readership. Not surprisingly, therefore, science-fiction readers often identified with the alien.

By the early 1950s, some science-fiction authors had begun using mass-market paperbacks as a literary vehicle to subtly question conventional attitudes about race and sexuality. The cover illustration on a 1952 book of short stories by Robert Heinlein featured the first visual depiction of a black astronaut, even though no such character was specifically described within the book, and publishers’ sales directors at the time expressly asked illustrators not to include African Americans on book covers, since it was assumed this would hinder sales south of the Mason–Dixon Line. A year later Weird Fantasy, a science-fiction comic book, published an allegory on American segregation in a story about an emerging civilization on a planet where orange robots are accorded privilege over the less entitled blue robots. In the story’s kicker ending, the space-suited emissary, who sits in judgment of the planet and denies its application for admission to a galactic republic, is revealed to be a black astronaut.

Robert Heinlein, who had also challenged social preconceptions about masculinity and femininity, wrote Tunnel in the Sky in 1955. In the young-adult novel, the race of the central protagonist is not overtly defined, but there are hints that he is black. Heinlein confessed that he used this literary device in an attempt to disarm his white readers, hoping that in the course of the narrative they would gradually come to realize the protagonist’s race after feeling empathy and identifying with him.

Writing in an essay for The New York Times shortly after his visit to Atlanta, Clarke addressed this issue as part of a larger defense of science fiction as literature. “Interplanetary xenophobia [in earlier science fiction] has given place to the idea that alien forms of life would have as much right to their points of view as we have. Such an attitude … can obviously help spread the idea of tolerance here on Earth (where heaven knows it’s needed).”

THE SUMMER THAT Arthur Clarke returned to the United States and was finishing the manuscript of Childhood’s End, he finally met Wernher von Braun, when both were guests at the Washington, D.C., home of the American Rocket Society’s president. In a lengthy diversion from a dinner conversation about humanity’s future in space, Clarke described his love of scuba diving and explained that it was an effective way to simulate the experience of being weightless in space. He then vigorously urged von Braun to take up the sport for the same reason, which von Braun did only a few weeks later, remaining an active diver for most of his life.

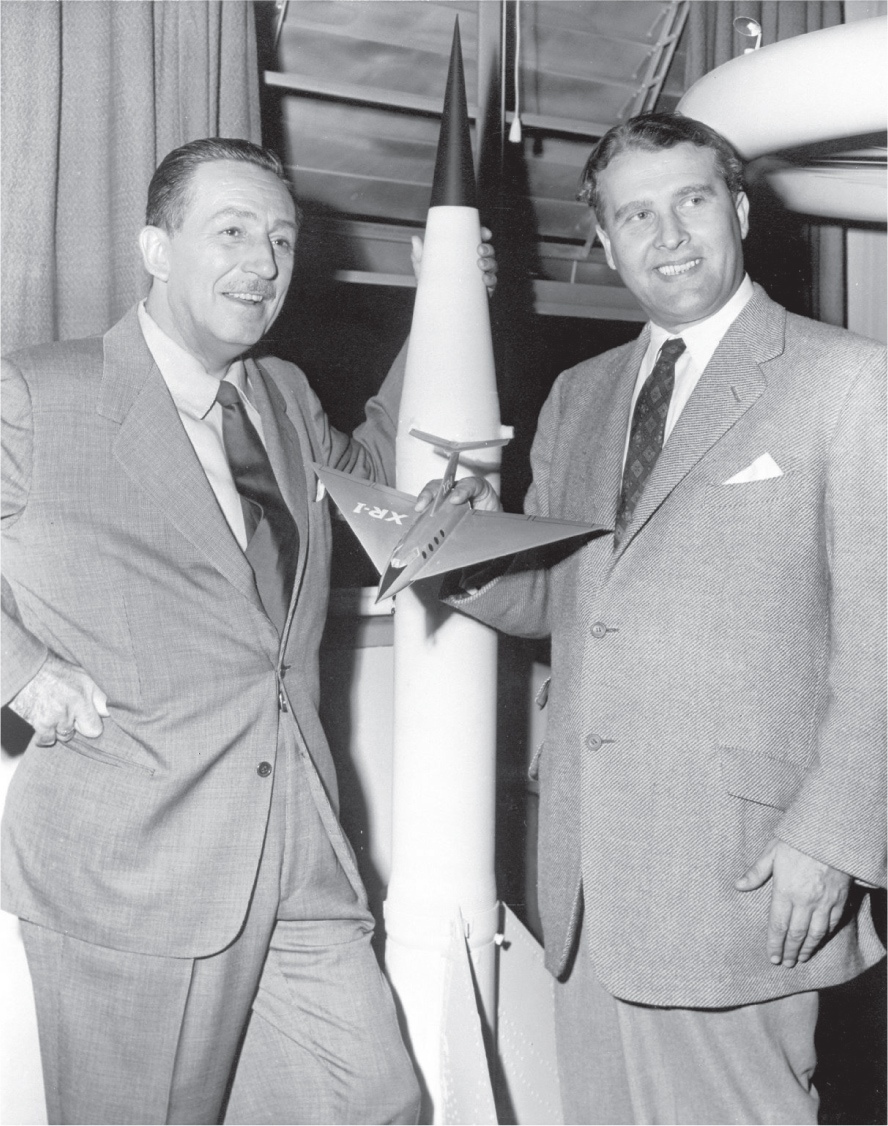

Even while overseeing the development of the Redstone rocket and working on a top-secret plan to quickly and inexpensively launch the first satellite into orbit, code-named Project Orbiter, von Braun continued his public advocacy for human spaceflight. An unexpected opportunity arose directly as a result of the Collier’s publications, just as the magazine released its eighth and final space-themed issue, featuring a description of the first human voyage to Mars. In early 1954, Hollywood came calling, in the person of Walt Disney, who was interested in producing a series of well-financed hour-long documentary films based on the magazine series. Disney was in the midst of creating a new prime-time TV program, Disneyland, which would mix recycled older content and new programming in order to promote another new venture, his California theme park, scheduled to open in 1955.

At the suggestion of one of his top animators, Ward Kimball, Disney approved three space-related “Tomorrowland” episodes adapted from Collier’s articles. The first episode, “Man in Space,” had Ley, von Braun, and Heinz Haber discussing rocketry history, orbital science, and the physical challenges facing humans during spaceflight, before concluding with an animated look into the near future as humans first entered space. Disney’s choice to feature three onscreen experts with distinctive German accents became an issue of concern within the studio prior to filming, until it was deemed that their authenticity was more valuable than any possible negative associations. The history portion of the program included World War II–era footage of V-2 launches, yet there was no mention of Nazi Germany’s part in rocket development; the V-2 was merely referred to reverently as “the forerunner of spaceships to come.” Among the featured experts, it was von Braun who commanded the viewer’s attention. Looking into the camera, he confidently asserted, “If we were to start today on an organized and well-supported space program, I believe a practical passenger rocket can be built and tested within ten years.”

© NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center

Walt Disney and Wernher von Braun in 1955 collaborating on “Man in Space,” one of three space exploration–themed episodes broadcast on Disney’s weekly television series in the 1950s. The programs were seen in more than a third of American households, including the White House, where President Dwight Eisenhower tuned in.

“Man in Space” premiered in the spring of 1955. Forty million households—more than a third of the American viewing public—watched the broadcast on their black-and-white televisions. Polling conducted that year revealed that nearly 40 percent of Americans believed “men in rockets will be able to reach the Moon” before the end of the century, a figure that had more than doubled in six years. Once again, von Braun’s space advocacy had political repercussions. One viewer who saw “Man in Space” lived at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, and after the broadcast Disney received a request from the Eisenhower White House for the loan of an exhibition print of the program so that it could be screened for Pentagon officials.

In nearly all of his entertainment, Disney promoted commonly accepted traditional American values. Though he kept his personal political attitudes out of the spotlight, Disney’s were conservative and anti-communist. Von Braun’s association with Disney therefore subtly bestowed an imprimatur of American respectability on the former official of the Third Reich. And in a final act of assimilation, a month after “Man in Space” aired, von Braun and more than one hundred other Germans working at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville appeared in a newsreel taking an oath of allegiance as they became U.S. citizens.

Von Braun was also celebrated in American public schools, many of which had recently introduced new audio-visual equipment into the classrooms. The Disney studio actively licensed 16mm exhibition prints of “Man in Space” as an entertaining teaching aid. Disney published a teacher’s study guide to use in conjunction with the screening, which featured von Braun’s photo on the cover and suggested classroom discussion questions such as “How likely is it that the present barriers between nations will tend to break down as contacts with other planets develop?”

Von Braun’s onscreen presence in the Disney programs coincided with his appearance in another far less visible film. Released in late 1955, the low-budget black-and-white Department of Defense film Challenge of Outer Space recorded an “officers’ conference” in which von Braun addressed a classroom of officers from various branches of the armed services. The content of his presentation paralleled the Disney films—and even included Collier’s illustrations. However, von Braun approached it almost entirely in terms of Cold War military superiority, something that was never mentioned in the “Man in Space” program. When discussing his space station, von Braun described it as something of “terrific military importance both as a reconnaissance station and as a bombing platform” with “unprecedented accuracy.”

Seated in front of an American flag, von Braun answered rehearsed questions from the officers, such as “Dr. von Braun, can you explain why it would be easier to bomb New York from a satellite than from a plane or a land-launched guided missile?” His response to such sobering questions was in marked contrast to his demeanor in the Disney production. He didn’t resort to colorful language to appeal to his listeners’ sense of wonder or innate desire to explore the unknown; there were no mentions of a “Columbus of space” or allusions to humanity’s evolutionary leap when first entering the cosmos. From his past experience, von Braun well knew that delivering his message to a room of grim-faced men wearing campaign ribbons necessitated very different rhetoric. He framed his talk entirely in terms of adversarial conflict and achieving strategic advantage and concluded with a note of warning: “The Russians are already hard at work, and if we are to be first, there is no time to lose.”

IN THE SPRING of 1955, the Eisenhower White House approved a proposal for the United States to orbit the world’s first satellite during the upcoming scientific International Geophysical Year. Modeled on International Polar Years of the past, the IGY would involve scientists from forty-six countries taking part in global geophysical activities and experiments from July 1957 through December 1958. The Soviet Union was believed to be on the verge of announcing its own satellite program, so the United States was attempting to stake its claim as well.

Very real Cold War concerns lay behind what appeared to be a purely scientific initiative. Since the beginning of the escalating nuclear-arms race, the two superpowers had been seeking a method to monitor the progress of their opponent’s weapons programs and their compliance with international agreements. Rather than using a high-altitude spy aircraft, which ran the risk of being shot down, the influential global-policy think tank, the RAND Corporation, proposed a space-age alternative: an unpiloted orbiting observational satellite that would either transmit video images or return exposed film reels via automated reentry capsules.

President Eisenhower believed that if a scientific research satellite was placed in an orbit that passed over the airspace of a Soviet Eastern Bloc country, this action would establish a precedent for orbital overflight, thus opening up space for observational reconnaissance. But from a diplomatic perspective this was an unsettled matter of international law. Eisenhower listened to other advisers, who cautioned that if the United States became the first to orbit an object over another nation’s sovereign territory, it risked international condemnation. They thought it wiser for the United States to hold off being first.

Von Braun’s secret Project Orbiter proposal was vying against two alternative plans, developed by the Air Force and the Navy. Orbiter was generally acknowledged to be the most sophisticated, practical, and reliable of the three proposals, but it was the Naval Research Laboratory’s Project Vanguard that got the official nod in late July 1955 when the White House made its announcement. (The projected launch wouldn’t occur until late 1957 or 1958.) Von Braun believed Project Orbiter had lost out to the Navy specifically because he had been involved. He wondered whether professional jealousy, his recent celebrity status, and prejudice about his German past, combined with the ever-present interservice rivalry, had contributed to his satellite’s rejection. Von Braun was so sensitive about reports of antagonism against him in Washington that when he learned that Disney’s publicists were planning to promote a rebroadcast of “Man in Space” with an ad line suggesting that the TV show led directly to the White House’s recent action, he vehemently implored them not to do so, fearing that some in Washington would assume he was using his Hollywood connections to take credit. “The statement would hurt the cause far more than it would help,” he told Disney’s producer.

In fact, a more important factor was involved in the selection. Giving the project to the Naval Research Laboratory was intended to deemphasize military and strategic implications, since the lab already had a reputation for conducting basic scientific research, unlike the Ordnance Guided Missile Center at Redstone Arsenal. The Navy planned to use modified research rockets with an established pedigree from past scientific-research experiments. In contrast, the Army intended to use a modified Redstone, which had been expressly developed to carry a nuclear explosive.

A memo written by Eisenhower’s secretary of defense, Charles Wilson, clarifying the nation’s missile-development responsibilities, only made matters worse for von Braun’s team. Wilson gave the Air Force responsibility for all future land-launched space missiles and limited the Army’s work to surface-to-surface battlefield weapons with a range of less than two hundred miles. At Redstone Arsenal and in the city of Huntsville, morale plummeted.

Four days after the White House’s announcement of Project Vanguard, Soviet space scientist Leonid I. Sedov addressed reporters at his country’s embassy in Copenhagen, where the annual congress of the International Astronautical Federation was being held. Much as the White House had expected, Sedov announced that the Russians would possibly launch a satellite in the next two years. When asked by a journalist about any German rocket specialists employed in Russia, Sedov adamantly insisted that none were working there.

Sedov’s assertion was largely correct, despite published rumors to the contrary. The full story didn’t emerge for decades. Joseph Stalin had personally authorized that nearly five hundred of the remaining rocket engineers from Peenemünde be forcibly transported to Russia in 1946. They were confined to isolated communities with little more than standard amenities, where they were subject to constant surveillance and the enmity of their Russian counterparts.

The Soviet Union’s closest equivalent to von Braun was Sergei Korolev, a Ukrainian-born engineer and strategic planner who, despite having spent six years in one of Stalin’s gulags, had risen to prominence as the chief rocket designer. Korolev distrusted the German engineers living in Russia, fearing that if they attained positions of importance they could possibly thwart his own ambitions and undermine the authority of his handpicked team of designers. Nevertheless, by the mid-1950s, and after wasting years working on projects of little importance, most of the captured Germans were finally allowed to return to the West.

A RINGING PHONE in the darkness immediately woke him. Arthur Clarke reached for his glasses and rose from the bed in his Barcelona hotel room to catch the call. The man’s voice on the other end of the line said he was calling from London. It was a journalist from the Fleet Street broadsheet the Daily Express, requesting a quotation in reaction to the breaking news. The reporter informed Clarke that minutes earlier the Soviet news agency, Tass, announced that Russia had successfully launched an artificial moon weighing 184 pounds into orbit around the Earth.

It was approaching midnight on October 4, 1957. Clarke was in Spain to attend that year’s International Astronautical Federation conference, and the call from London placed him in a privileged position among those who had arrived. Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s regime maintained an international news blackout; nothing appeared in newspapers or on the radio until it had been cleared for public release. Most of the other conference delegates remained ignorant of the Soviet Union’s triumph until those arriving late brought the news of the outside world with them. But within a few days everyone knew a new Russian word, “Sputnik,” meaning “fellow traveler.” The provocative response that Clarke gave to the reporter that night received attention in newspapers around the world as well: “As of Saturday the United States became a second-rate power.”

Clarke’s words did not sit well with William Davis, an American Air Force colonel. “I heard that and I didn’t like it! Space is the next major area of competition. If this one is lost, we might as well quit.” Colonel Davis suggested the United States should counteract the Soviet propaganda by readying its own space vehicle, with a human on board.

Missing from the Barcelona conference was Wernher von Braun. It was still Friday evening in Huntsville when a British journalist called his office at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, the successor to the Ordnance Guided Missile Center. Von Braun had feared this day would come, and his sense of disappointment was mixed with anger. He had no doubt that had the United States government given him the opportunity, he would have placed the first artificial satellite in orbit.

At a press conference a few days later, President Eisenhower congratulated the Soviets but dismissed the idea of a race with Russia. He emphasized that both superpowers were engaged in an international program of scientific research. Eisenhower attempted to explain the Soviets’ success by casually noting that “the Russians captured all the German scientists at Peenemünde,” a remark that astounded many in Huntsville, as it was an outright lie. Unstated by Eisenhower was his relief that Russia had established the controversial precedent of orbital overflight. In the future, neither the Soviets nor other nations could voice their diplomatic objections when the United States eventually orbited its planned surveillance satellites.

The American media’s reaction to Sputnik was far less measured than the president’s. Columnists bemoaned the shocking loss of national prestige and criticized Eisenhower’s blasé reaction as lack of leadership. Opposition politicians appeared on television, expressing fear that the Soviets might use their powerful rockets to position a nuclear sword of Damocles above any nation.

Overshadowed by the news of Sputnik was another event at the Barcelona astronautical conference that captured the Cold War zeitgeist. Dr. S. Fred Singer, a young Austrian-born physicist noted for his work in cosmic radiation, was there to deliver a provocative paper. One of von Braun’s Project Orbiter colleagues and a leading member of the American Astronautical Society, Singer had also cultivated a talent for getting his name into print by fearlessly saying things his more prudent scientific colleagues would avoid.

Singer’s paper was titled “Interplanetary Ballistic Missiles: A New Astrophysical Research Tool” and argued in favor of exploding thermonuclear bombs on the Moon as a way to conduct scientific research. It was an idea that, he said, was “not only peaceful, but also useful, and, therefore, worthwhile.” This proposal, he believed, might lead to other experiments, such as exploding thermonuclear devices on the planets or an attempt to create a new star. But more immediately, Singer suggested, this initiative would promote world peace, as “the H-bomb race between the big powers would then be reduced to the much more tractable problem of seeing who could make the bigger crater on the Moon.” He was especially excited by the possibility of rearranging lunar geography. “The idea of creating a permanent crater as a mark of man’s work is an appealing one,” he said. “One is left with a nice crater on the Moon which is unnamed and therefore provides unique opportunities for perpetuating the names of presidents, prime ministers, and party secretaries.”

The Soviet delegates sitting in the lecture hall listened to Singer’s proposal with understandable astonishment and outrage. However, Singer later remarked that the Soviet reaction to his paper was “blown out of proportion.”

As Sputnik dominated the headlines, newspapers gave less attention to the big story out of Little Rock, Arkansas, where a week earlier President Eisenhower had ordered 1,200 members of the Army’s 101st Airborne Division to assist with the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. The day before Eisenhower’s order to mobilize the troops, more than a thousand white protesters had rioted to prevent nine black students from attending the school. After Sputnik was launched, Radio Moscow seized upon an opportunity to shame the United States for hypocritically calling itself “the land of the free”: It alerted its global listeners to the exact moment when the satellite would pass over Little Rock, news that was specifically intended to be heard in the emerging independent nations of Africa.

Incensed that he and his new boss at Huntsville’s Army Ballistic Missile Agency, General John Medaris, hadn’t been given an opportunity to ready a modified Redstone rocket to launch a swift response to Sputnik, von Braun covertly made his case in the media, despite having received orders from Washington not to make any public comments. Magazine features called him “The Prophet of the Space Age” and “The Seer of Space,” portraying him as the brilliant visionary whose bold ideas had been ignored by petty bureaucrats, unimaginative military officials, and cowardly politicians. And knowing that nothing motivated people as powerfully as fear, von Braun evoked the specter of atomic annihilation, arguing that it was imperative that the United States establish its superiority in space if the nation was to survive.

Eisenhower became increasingly irritated by von Braun’s arrogance, celebrity status, and self-serving pronouncements. In fact, the president’s growing frustration with von Braun likely accounted for his wildly inaccurate comment at his press conference about the Russians having all the German scientists. If it had been intended to belittle von Braun’s reputation and public profile, it backfired badly.

The media panic only increased when in early November the Soviets orbited Sputnik 2. A much heavier satellite, it carried the first living creature on a one-way trip into orbit, the photogenic husky-terrier mix, Laika. NBC’s Merrill Mueller, a reporter who had covered D-Day, the Battle of the Bulge, and the bombing of Hiroshima, grimly faced the television camera as he told viewers, “The rocket that launched Sputnik 2 is capable of carrying a ton-and-a-half hydrogen-bomb warhead.”