Полная версия

Chasing the Moon

THE SENSATIONAL ATTENTION accorded Goddard’s Smithsonian paper appeared in the European press just as the third of the trio of rocketry pioneers, a former medical student from Austro-Hungaria named Hermann Oberth, was readying his work for academic review. Born in 1894, Oberth was a brilliant student of mathematics and had been fascinated by the idea of spaceflight since age twelve, when he committed to memory passages from Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon. Oberth had tried to interest military strategists in a proposal for long-range missiles during the First World War, but his paper went unread. After the war he revised his work, this time focusing on the basic mathematics underlying space travel. However, when he submitted the paper as his doctoral dissertation, it was rejected as “too fantastic.”

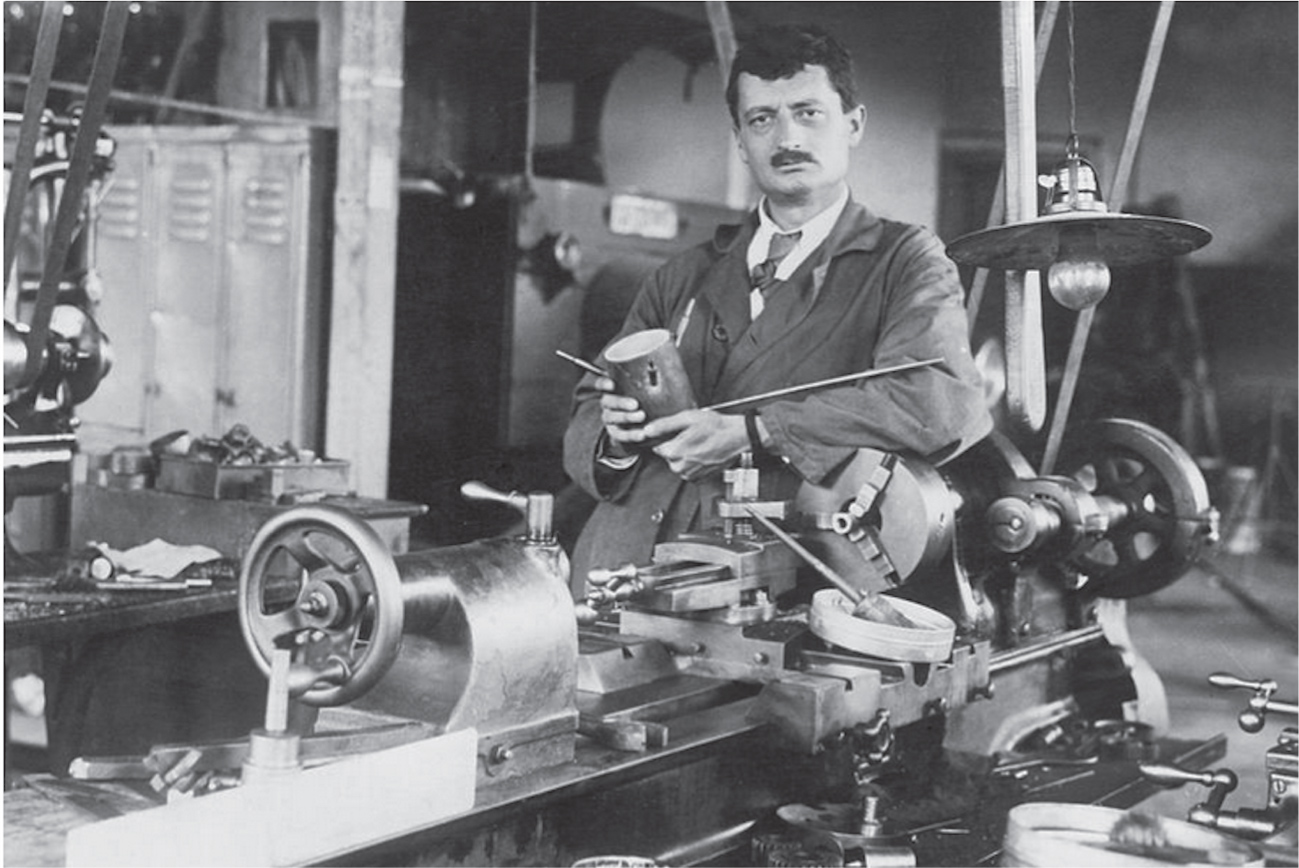

© Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM 87-5770)

Hermann Oberth photographed in his workshop while assisting on the production of the German science-fiction feature film Woman in the Moon. When he was ten years old, the telephone and the automobile first appeared in his rural hometown. In his later years he witnessed the launches of Apollo 11 and the space shuttle Challenger.

Undeterred, Oberth obstinately continued to pursue his studies independently, dismissing his instructors as unworthy to judge his work. For this gifted mathematician, formulating the necessary calculations for space travel was a diverting intellectual exercise that gave him a sense of ownership and agency. “This was nothing but a hobby for me,” he said, “like catching butterflies or collecting stamps for other people, with the only difference that I was engaged in rocket development.”

He asked himself a series of questions that would need to be answered if humans were to enter outer space: Which propellant should be used—liquid or solid? Is interplanetary travel possible? Can humans adapt to weightlessness? How might humans nourish themselves in space? Can humans wearing space suits venture outside vehicles? In contrast to Goddard’s more cautious approach, Oberth embraced the unknown by posing imaginative questions prompted by his reading of science fiction. He then devised practical solutions founded on his mathematical and engineering expertise.

In 1923 he published a short technical version of his dissertation, Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket into Interplanetary Space), personally paying the expense of the book’s entire printing. Fortunately, his vanity-publishing project was a wise decision. By issuing the book in German, which in the early twentieth century was the dominant language of the scientific community, Oberth established himself as the world’s leading theorist of human spaceflight, overshadowing the more reclusive Goddard. When he read the German monograph, Goddard believed Oberth had borrowed his ideas without proper attribution, though there is little evidence to support his suspicions.

The Rocket into Interplanetary Space appeared at a moment when many Germans were hungry for something bold, dynamic, and modern to restore the nation’s pride, following the defeat in World War I. The 1920s were a time of experimentation in art, film, and architecture and the arrival of new consumer technologies like radio, air travel, and neon lighting. The speed, power, and streamlined design of rockets became associated with a future of exciting possibilites. Less than four years after the publication of Oberth’s book, the Verein für Raumschiffahrt—or Society for Space Travel—was formed in Germany, and it soon became the world’s leading rocketry organization. It published a journal, held conferences, and conducted research experiments. But the stunts of Max Valier, one of the society’s founders, were what drew the greatest media attention: He strapped himself into a rocket-powered car and hurtled down a racetrack, trailing a cloud of smoke and flame. Such daredevil exploits proved to be an effective way of generating publicity but did little to boost the society’s scientific reputation.

Not long after the society’s founding, the noted Austrian-German filmmaker Fritz Lang approached it for technical assistance in connection with his forthcoming science-fiction space epic, Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon), a follow-up to his international hit Metropolis. Lang hired Oberth, the society’s figurehead president, to be the film’s technical adviser. The film’s studio also engaged Oberth to build a functioning liquid-fuel rocket to promote the movie’s premiere, a project that, despite providing the society needed research-and-development money, was unsuccessful.

Albert Einstein and other scientists were among the celebrities who attended the film’s opening, but the only rocket to be seen that night was the one that appeared on the screen, created by the studio’s special-effects department. Although Frau im Mond wasn’t a critical hit, it was historically important for introducing the world’s first rocket countdown. Fritz Lang created it as a dramatic device to instill suspense in the final moments before the blastoff. It was such an effective way to focus attention and convey the sequence of procedures prior to liftoff that rocket engineers around the world immediately adopted it.

Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, reports of Goddard’s moon rocket and Oberth’s scientific monograph prompted Russian space enthusiasts to stake their country’s claim by recognizing that Konstantin Tsiolkovsky had been the first to mathematically publish the rocket equation. Tsiolkovsky was in his mid-sixties when he received his vindication, and it coincided with a brief and bizarre moment of space-travel mania. After the First World War, revolution, and a civil war, Russia was in the throes of change, as audacious and provocative new ideas permeated the culture; among them was a renewed interest in utopian Russian cosmism, and a desire to explore new worlds. One of Tsiolkovsky’s leading Soviet advocates rallied followers with the slogan “Forward to Mars!”

In 1924, Russian magazines and newspapers reported that Goddard was about to shoot his rocket to the Moon or, in fact, may have already done so. Many Russian readers assumed that colonizing the planets was imminent. At space-advocacy lectures and public programs—including one with a crowd so keyed up that a riot nearly took place—curious attendees demanded to know when flights to the Moon and planets would commence and where to volunteer to be among the first settlers. But after learning that trips to the planets were at least a few decades away, the crowd dispersed in disappointment. In Moscow, an international space exhibition attracted twelve thousand visitors, and a Russian Society for Studies of Interplanetary Travel was founded. But Stalin’s rise to power and the beginning of the Five-Year Plan brought an end to Russia’s short experimental post-revolutionary sojourn. Despite his new fame at home, Tsiolkovsky received little recognition abroad.

Goddard’s reticence for publicity may partly account for the reason that, unlike in Germany and the Soviet Union, no comparable rocketry fad occurred in 1920s America. Instead, a different and more long-lasting phenomenon, which proved influential for the emergence of the space age, arose in the United States: the publication of the first popular science-fiction magazines. In 1926, Hugo Gernsback, an immigrant who had built a business issuing cheaply printed magazines about electronics and radio, introduced Amazing Stories, a specialty-fiction publication for which he coined the term “scientifiction.” Not long after, Gernsback hired a young technical writer named David Lasser to serve as the editor of a new publication, Science Wonder Stories. Lasser, the son of Russian immigrant parents, had enlisted in the Army and experienced combat during the First World War by the age of sixteen. Following months of hospitalization due to the injuries he sustained in a poison-gas attack, Lasser used a disabled-veterans scholarship to attend and graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Avid readers noticed that, shortly after Lasser’s name appeared on the masthead of the Gernsback magazines, their literary quality improved significantly.

Lasser had become intrigued by press accounts about Goddard, Oberth, and Germany’s Verein für Raumschiffahrt, and in April 1930 he and fellow New York science-fiction writers and editors formed the American Interplanetary Society. Much like the Verein für Raumschiffahrt, its American counterpart aimed to stimulate awareness, enthusiasm, and advocate for private funding of rocket research—while also expanding the readership for Gernsback’s magazines. Goddard informed Lasser that he approved of the American Interplanetary Society’s mission but abstained from becoming a member. The Clark University professor apparently feared that if it were known he associated with science-fiction enthusiasts, research grant donors might question his judgment and reluctantly withdraw their support.

In one of his first roles as the president of the American Interplanetary Society, Lasser presided over a special event held at New York’s American Museum of Natural History: a lecture about space travel, featuring one of the first American screenings of Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond. Though a modest-sized audience had been expected, nearly two thousand curious New Yorkers converged on the museum. The only way to accommodate the sizable audience was to add a second screening later that evening.

David Lasser had concluded that there was a need for a book written for curious readers that explained in realistic, accurate, but understandable scientific terms the fundamentals of rocket science, why constructing an operational vehicle should be attempted, and what piloted space travel would mean to humanity. Lasser believed that once humans departed their home planet, a philosophical and political shift would occur throughout the world as people began to perceive the Earth as a small, fragile, isolated sphere in the emptiness of space. This change in thought, he concluded, would lead to the erosion of the dangerous nationalistic and tribal divisions that had brought about the recent carnage of the First World War. He wanted his book to provide the fundamental scientific concepts while forgoing the higher mathematics that might intimidate some readers.

Researching the book, Lasser gathered recently published technical papers from leading scientific journals and corresponded with rocketry activists around the world. He wrote it during the immediate aftermath of the Wall Street Crash, a time when he and many other Americans hoped for a better future. Lasser’s optimism colors his imaginary account of the moment when news from the first lunar space travelers is received on Earth: “We learn that wild excitement prevails all over the globe…. We cannot but feel now that this journey has served its purpose in the breaking down of racial jealousies.” Elsewhere he writes that space travel will result in a new planetary outlook, the realization that “the whole Earth is our home.”

Unfortunately, the early years of the Great Depression were not a good time to publish such a book. Lasser and members of the American Interplanetary Society financed the publication of The Conquest of Space, but sales were modest. The British rights were sold to a small but venerable publisher, which issued a few thousand copies. Serendipitously, one crucial copy found its way into the hands of teenage Arthur C. Clarke after being displayed in the bookshop window in southwest England.

WHEN HE READ Lasser’s book, Archie Clarke was already familiar with the world of American science-fiction magazines. Unsold copies returned from newsstands and drugstores were used as ballast in the holds of the great transatlantic liners sailing between New York and Great Britain. Once they arrived in England, the magazines were sold in shops for a few pence each, including the Woolworth’s store across the street from Archie’s grammar school, where he often searched through piles of American detective, Western, and romance pulps for the newest science-fiction issues. He soon amassed a substantial collection and compiled a catalog of his reading, scoring stories with a grade ranging from F (fair) to VVG (very, very good).

But when he read The Conquest of Space he realized for the first time that “space travel was not merely fiction. One day it could really happen.” Shortly before reading Lasser’s book, Archie had been fascinated by Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men, an ambitious philosophical novel contemplating the evolutionary fate of the human race hundreds of thousands of years hence. Lasser’s suggestion that space exploration would signal the transformation of the human species was a provocative idea, and Clarke yearned to see it happen in his lifetime. He wanted to meet and exchange ideas with others who also shared these dreams of space and adventure.

A small, unelectrified, three-hundred-year-old stone farmhouse in a southwestern English village was the unlikely home where one of the twentieth century’s most visionary minds began dreaming about humanity’s destiny in the stars. Archie Clarke’s parents had both been telegraph operators at different branches of the General Post Office, where, prior to the First World War, they had conducted a covert courtship via Morse code when not under the gaze of their supervisors. Archie had been born while his father, a lieutenant in the Royal Engineers, was stationed in France, later to return badly disabled.

Like many other curious boys, Archie had gone through an early fascination with dinosaurs, an interest sparked at age five when his father casually handed him a cigarette card illustrated with a picture of a stegosaurus. Clarke later attributed his passion for scientific subjects to that moment with his father. An intense interest in electronics, chemistry, and astronomy soon followed, and with the aid of an inexpensive telescope he began mapping the features of the Moon in a composition book. A private grammar school in a neighboring town awarded him a full scholarship, and although he was socially at ease with these more privileged classmates, he was aware he was different. In appearance and background, Archie’s modest bucolic home life set him apart. He usually arrived at school wearing unfashionable short pants and large farm boots, which often carried the lingering odor of the barnyard.

Despite his excellent grades, he knew there was little likelihood he could obtain a university education, due to his family’s financial circumstances. He loved reading stories in the American magazines that asked “What if?” and subtly questioned conventionally accepted assumptions and rules—both scientific and cultural. In particular, he was immensely impressed by one short story that sympathetically attempted to portray a truly alien “other” and prompted the reader to try to understand distinctly non-human motivations and thought processes. Clarke found within the pages of the science-fiction magazines an invigorating American sense of optimism and intimations of a future with greater opportunities. And before long they also provided a pathway to a community of like minds.

BY THE TIME Clarke read The Conquest of Space, almost all publicly sanctioned rocket activity in Germany was nearing an end. Max Valier, world-famous for his rocket-car exploits, was killed during a test of an experimental liquid-fuel rocket engine in 1930—the first human casualty of the space age. A rift had also developed among the Verein für Raumschiffahrt’s officers. One faction thought rockets should be used for scientific exploration, not as weapons, while others urged the society to partner with the German military.

© NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center

Members of the German rocket society Verein für Raumschiffahrt. Hermann Oberth stands to the right of the large experimental rocket, wearing a dark coat, while teenage Wernher von Braun appears behind him, second from the right.

As Europe entered the Great Depression, the society’s officers who favored ties with the military exerted greater control and obtained the use of an abandoned German army garrison near Berlin in which to conduct their experiments. Headquartered in an old barracks building, a dedicated corps of unemployed engineers built a launch area and a test stand—a stationary structure on which a liquid-fuel rocket engine could be tested under controlled conditions. All of the serious, highly dedicated engineers were unmarried young men who chose to live with military-like discipline. None either smoked or drank.

Among the most active of the young engineers, one man stood out. An intelligent, blue-eyed, bright-blond-haired eighteen-year-old aristocrat, Wernher von Braun had chosen to dedicate his life to making space travel to other planets a reality. At the old army barracks and rocket testing ground, he acquired valuable hands-on experience designing and launching prototype liquid-fuel rockets in collaboration with Oberth and the other engineers. Von Braun’s dedication and ambition soon caught the attention of a group of men who had arrived one morning to observe a test of one of the new rockets. Though dressed as civilians, they were officers from the German Army’s ordnance ballistics-and-munitions section, quietly conducting research into future weapons. The Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, had imposed restrictions on German military rearmament. However, since rocketry was a new technology not specified in the treaty, rocket-weapons development fell outside its constraints.

In all, the small group of young engineers conducted nearly one hundred rocket launches before the site was finally closed down due to police-imposed safety restrictions and the society’s own unpaid bills. But by the time the garrison was shuttered, von Braun had disappeared. Among his former colleagues, it was assumed that he was conducting research elsewhere, though occasional rumors suggested he might be involved in something highly secretive. The extent of the mystery did not become known to the world for another fifteen years.

In debt and its reputation in disarray, the Verein für Raumschiffahrt suffered further derision when some members attempted to use the society to promote pseudoscience and nationalist politics. Before his untimely death, Max Valier had endorsed theories about Atlantis, Lemuria, and other popular occultist ideas. One of the society’s remaining officers depleted the organization’s dwindled funds to finance a public rocket launch intended to prove the validity of the Hohlweltlehre—a bizarre doctrine that asserted that the Earth is actually the interior of a giant hollow sphere. Reputable scientists would have nothing to do with it, and the Verein für Raumschiffahrt came to an ignominious end just as the new Nazi government imposed prohibitions against any future public discussions about rocket technology or research.

The little news that trickled out of Russia indicated that nearly all interest in rocketry had subsided under the Five-Year Plan. And in the United States, by the time Clarke read The Conquest of Space, the life of the book’s author had changed dramatically as well. While promoting interest in space travel, David Lasser had discovered he had a natural talent for organizing people, planning events, and generating public attention. Not long after the screening at the Museum of Natural History, he began to devote a portion of his time to socialist politics and organizing to effect political change. Unemployment in the United States was approaching 25 percent; in Lasser’s Greenwich Village neighborhood, nearly 80 percent of the residents were out of work. He believed the most important question before the country at that time wasn’t human space travel but reducing unemployment. For the moment, space would have to wait.

Lasser’s boss took a dim view of his political activism. Hugo Gernsback wanted him in the office every day, editing the latest issue of Science Wonder Stories, rather than taking time off to consult with the mayor of New York on unemployment issues. Exasperated, Gernsback summoned Lasser into his office and told him, “If you like working with the unemployed so much, I suggest you go and join them.” Fired by the world’s leading publisher of science fiction, Lasser’s short career as America’s first advocate for space travel came to an end as well. His career change took him to an important job in Washington, D.C., where he was tapped to run the Workers Alliance of America, a trade union for those temporarily employed by the Works Progress Administration of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

At nearly the same moment that he dismissed David Lasser, Gernsback made a second decision that would significantly impact the life of Archie Clarke, a continent away. Eager to increase customer loyalty for his magazines, Gernsback introduced a readers’ club, the Science Fiction League, the world’s first science-fiction fan organization. Within a few months it had close to one thousand members, spread among three continents. Not long after, they began publishing unaffiliated newsletters, engaging in private correspondence, and traveling to meet one another.

One of Gernsback’s competitors, Astounding Stories, started publishing readers’ letters in its pages, including the correspondents’ addresses. While poring through one of those issues, Archie Clarke read that a British Interplanetary Society had been founded in Liverpool a few months earlier. Now sixteen and having suddenly discovered a community of like minds, Archie wrote to the British society’s secretary, volunteering his services. “I am extremely interested in the whole subject of interplanetary communications, and have made some experiments with rockets.” To impress the society’s board, he added that he had “an extensive knowledge of physics and chemistry and possess a small laboratory and apparatus with which I can do some experiments.”

Within two years he had assumed a position of leadership as one of the society’s most influential board members.

ON ITS FINAL transatlantic voyage, in 1935, the Cunard–White Star liner Olympic arrived in New York City, a day late after encountering severe February winds. Journalists who met the ship at the pier reported that one of the passengers, Mr. Willy Ley of Berlin, age twenty-eight, would be spending seven months in the United States, working with Americans on a project to transport the mail by rocket.

One of the founders of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt, Ley had studied astronomy, physics, and zoology at the universities of Berlin and Konigsberg, and by the mid-1920s he had become one of Germany’s leading advocates for human spaceflight. He was among the society’s strongest voices against rocket-weapons research, believing that rockets should be used for peaceful scientific and exploratory pursuits exclusively. Ley had been disdainful of Max Valier’s stunts with his rocket-powered car but was all for raising public awareness about spaceflight via popular entertainment. He worked with Fritz Lang during the making of Frau im Mond and had become the filmmaker’s close friend. Ley had even written a science-fiction novel, Die Starfield Company, an adventure in which the hero battles with space pirates that also includes an interracial love story and a parable about international cooperation.

In his leadership role with the Verein für Raumschiffahrt, Ley had been in contact with rocketry researchers and space-travel societies around the world, and he continued to do so until 1933, when the Nazis prohibited any exchange of technical and scientific information about rocketry with citizens of foreign countries. A strong believer in furthering intellectual inquiry through the free exchange of ideas, Ley was deeply bothered by what was happening in Germany.

He watched as scientists and researchers in many disciplines were purged from German academic institutions—primarily for racial reasons—and learned that selected scientific publications were being removed from library shelves. On university campuses, the Nazis conducted public book burnings. Besides scientific works by Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud and literature by Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann, the Nazis had also consigned many classic works of science fiction to the bonfires.