полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

Few combats have been more resolutely contested. The "Saratoga" had fifty-five round shot in her hull; the "Confiance," one hundred and five.435 Of the American crew of two hundred and ten men, twenty-eight were killed and twenty-nine wounded. The British loss is not known exactly. Robertson reported that there were thirty-eight bodies sent ashore for interment, besides those thrown overboard in action. This points to a loss of about fifty killed, and James states the wounded at about sixty; the total was certainly more than one hundred in a ship's company of two hundred and seventy.

There was reason for obstinacy, additional to the natural resolution of the parties engaged. The battle of Lake Champlain, more nearly than any other incident of the War of 1812, merits the epithet "decisive." The moment the issue was known, Prevost retreated into Canada; entirely properly, as indicated by the Duke of Wellington's words before and after. His previous conduct was open to censure, for he had used towards Captain Downie urgency of pressure which induced that officer to engage prematurely; "goaded" into action, as Yeo wrote. Before the usual naval Court Martial, the officers sworn testified that Downie had been led to expect co-operation, which in their judgment would have reversed the issue; but that no proper assault was made. Charges were preferred, and Prevost was summoned home; but he died before trial. There remains therefore no sworn testimony on his side, nor was there any adequate cross-examination of the naval witnesses. In the judgment of the writer, it was incumbent upon Prevost to assault the works when Downie was known to be approaching, with a fair wind, in the hope of driving the American squadron from its anchors to the open lake, where the real superiority of the British could assert itself.436

Castlereagh's "chances of the campaign" had gone so decidedly against the British that no ground was left to claim territorial adjustments. To effect these the war must be continued; and for this Great Britain was not prepared, nor could she afford the necessary detachment of force. In the completeness of Napoleon's downfall, we now are prone to forget that remaining political conditions in Europe still required all the Great Powers to keep their arms at hand.

The war was practically ended by Prevost's retreat. What remained was purely episodical in character, and should be so regarded. Nevertheless, although without effect upon the issue, and indeed in great part transacted after peace had been actually signed, it is so directly consecutive with the war as to require united treatment.

Very soon after reaching Bermuda, Vice-Admiral Cochrane, in pursuance of the "confidential communications with which he was charged," the character of which, he intimated to Warren,437 was a reason for expediting the transfer of the command, despatched the frigate "Orpheus" to the Appalachicola River to negotiate with the Creek and other Indians. The object was to rouse and arm "our Indian allies in the Southern States," and to arrange with them a system of training by British officers, and a general plan of action; by which, "supporting the Indian tribes situated on the confines of Florida, and in the back parts of Georgia, it would be easy to reduce New Orleans, and to distress the enemy very seriously in the neighboring provinces."438

The "Orpheus" arrived at the mouth of the Appalachicola May 10, 1814, and on the 20th her captain, Pigot, had an interview with the principal Creek chiefs. He found439 that the feeling of their people was very strong against the Americans; and from the best attainable information he estimated that twenty-eight hundred warriors were ready to take up arms with the British. There were said to be as many more Choctaws thus disposed; and perhaps a thousand other Indians, then dispersed and unarmed, could be collected. The negroes of Georgia would probably also come over in crowds, once the movement started. With a suitable number of British subalterns and drill sergeants, the savages could be fitted to act in concert with British troops in eight or ten weeks; for they were already familiar with the use of fire-arms, and were moreover good horsemen. The season of the year being still so early, there was ample time for the necessary training. With these preparations, and adequate supplies of arms and military stores, Pigot thought that a handful of British troops, co-operating with the Creeks and Choctaws, could get possession of Baton Rouge, from which New Orleans and the lower Mississippi would be an easy conquest. Between Pensacola, still in the possession of Spain, and New Orleans, Mobile was the only post held by the United States. In its fort were two hundred troops, and in those up country not more than seven hundred.

When transmitting this letter, which, with his own of June 20, was received at the Admiralty August 8, Cochrane endorsed most of Pigot's recommendations. He gave as his own estimate, that to drive the Americans entirely out of Louisiana and the Floridas would require not more than three thousand British troops; to be landed at Mobile, where they would be joined by all the Indians and the disaffected French and Spaniards.440 In this calculation reappears the perennial error of relying upon disaffected inhabitants, as well as savages. Disaffection must be supported by intolerable conditions, before inhabitants will stake all; not merely the chance of life, but the certainty of losing property, if unsuccessful. Cochrane took the further practical step of sending at once such arms and ammunition as the fleet could spare, together with four officers and one hundred and eight non-commissioned officers and privates of the marine corps, to train the Indians. These were all under the command of Major Nicholls, who for this service was given the local rank of Colonel. The whole were despatched July 23, in the naval vessels "Hermes" and "Carron," for the Appalachicola. The Admiral, while contemplating evidently a progress towards Baton Rouge, looked also to coastwise operations; for he asked the Government to furnish him vessels of light draught, to carry heavy guns into Lake Ponchartrain, and to navigate the shoal water between it and Mobile, now called Mississippi Sound.

The Admiralty in reply441 reminded Cochrane of the former purpose of the Government to direct operations against New Orleans, with a very large force under Lord Hill, Wellington's second in the Peninsular War. Circumstances had made it inexpedient to send so many troops from Europe at this moment; but, in view of the Admiral's recommendation, General Ross would be directed to co-operate in the intended movement at the proper season, and his corps would be raised to six thousand men, independent of such help in seamen and marines as the fleet might afford. The re-enforcements would be sent to Negril Bay, at the west end of Jamaica, which was made the general rendezvous; and there Cochrane and Ross were directed to join not later than November 20. The purpose of the Government in attempting the enterprise was stated to be twofold. "First, to obtain command of the embouchure of the Mississippi, so as to deprive the back settlements of America of their communication with the sea; and, secondly, to occupy some important and valuable possession, by the restoration of which the conditions of peace might be improved, or which we might be entitled to exact the cession of, as the price of peace." Entire discretion was left with the two commanders as to the method of proceeding, whether directly against New Orleans, by water, or to its rear, by land, through the country of the Creeks; and they were at liberty to abandon the undertaking in favor of some other, should that course seem more suitable. When news of the capture of Washington was received, two thousand additional troops were sent to Bermuda, under the impression that the General might desire to push his success on the Atlantic coast. These ultimately joined the expedition two days before the attack on Jackson's lines. Upon the death of General Ross, Sir Edward Pakenham was ordered to replace him; but he did not arrive until after the landing, and had therefore no voice in determining the general line of operations adopted.

These were the military instructions. To them were added certain others, political in character, dictated mainly by the disturbed state of Europe, and with an eye to appease the jealousies existing among the Powers, which extended to American conditions, colonial and commercial. While united against Napoleon, they viewed with distrust the aggrandizement of Great Britain. Ross was ordered, therefore, to discountenance any overture of the inhabitants to place themselves under British dominion; but should he find a general and decided disposition to withdraw from their recent connection with the United States, with the view of establishing themselves as an independent people, or of returning under the dominion of Spain, from which they then had been separated less than twenty years, he was to give them every support in his power. He must make them clearly understand, however, that in the peace with the United States neither independence nor restoration to Spain could be made a sine quâ non;442 there being about that a finality, of which the Government had already been warned in the then current negotiations with the American commissioners. These instructions to Ross were communicated to Lord Castlereagh at Vienna, to use as might be expedient in the discussions of the Conference.

No serious attempt was made in the direction of Baton Rouge, through the back countries of Georgia and Florida; nor does there appear any result of consequence from the mission of Colonel Nicholls. On September 17 the "Hermes" and "Carron," supported by two brigs of war, made an attack upon Fort Bowyer, a work of logs and sand commanding the entrance to Mobile Bay. After a severe cannonade, lasting between two and three hours, they were repulsed; and the "Hermes," running aground, was set on fire by her captain to prevent her falling into the hands of the enemy. Mobile was thus preserved from becoming the starting point of the expedition, as suggested by Cochrane; and that this object underlay the attempt may be inferred from the finding of the Court Martial upon Captain Percy of the "Hermes," which decided that the attack was perfectly justified by the circumstances stated at the trial.443

In October, 1810, by executive proclamation of President Madison, the United States had taken possession of the region between Louisiana and the River Perdido,444 being the greater part of what was then known as West Florida. The Spanish troops occupying Mobile, however, were not then disturbed;445 nor was there a military occupation, except of one almost uninhabited spot near Bay St. Louis.446 This intervention was justified on the ground of a claim to the territory, asserted to be valid; and occasion for it was found in the danger of a foreign interference, resulting from the subversion of Spanish authority by a revolutionary movement. By Great Britain it was regarded as a usurpation, to effect which advantage had been taken of the embarrassment of the Spaniards when struggling against Napoleon for national existence. On May 14, 1812, being then on the verge of war with Great Britain, the ally of Spain, an Act of Congress declared the whole country annexed, and extended over it the jurisdiction of the United States. Mobile was occupied April 15, 1813. Pensacola, east of the Perdido, but close to it, remained in the hands of Spain, and was used as a base of operations by the British fleet, both before and after the attack of the "Hermes" and her consorts upon Fort Bowyer. From there Nicholls announced that he had arrived in the Floridas for the purpose of annoying "the only enemy Great Britain has in the world"447; and Captain Percy thence invited the pirates of Barataria to join the British cause. Cochrane also informed the Admiralty that for quicker communication, while operating in the Gulf, he intended to establish a system of couriers through Florida, between Amelia Island and Pensacola, both under Spanish jurisdiction.448 On the score of neutrality, therefore, fault can scarcely be found with General Jackson for assaulting the latter, which surrendered to him November 7. The British vessels departed, and the works were blown up; after which the place was restored to the Spaniards.

In acknowledging the Admiralty's letter of August 10, Cochrane said that the diminution of numbers from those intended for Lord Hill would not affect his plans; that, unless the United States had sent very great re-enforcements to Louisiana, the troops now to be employed were perfectly adequate, even without the marines. These he intended to send under Rear-Admiral Cockburn, to effect a diversion by occupying Cumberland Island, off the south coast of Georgia, about November 10, whence the operations would be extended to the mainland. It was hoped this would draw to the coast the American force employed against the Indians, and so favor the movements in Louisiana.449 While not expressly stated, the inference seems probable that Cochrane still—October 3—expected to land at Mobile. For some reason Cockburn's attack on Cumberland Island did not occur until January 12, when the New Orleans business was already concluded; so that, although successful, and prosecuted further to the seacoast, it had no influence upon the general issues.

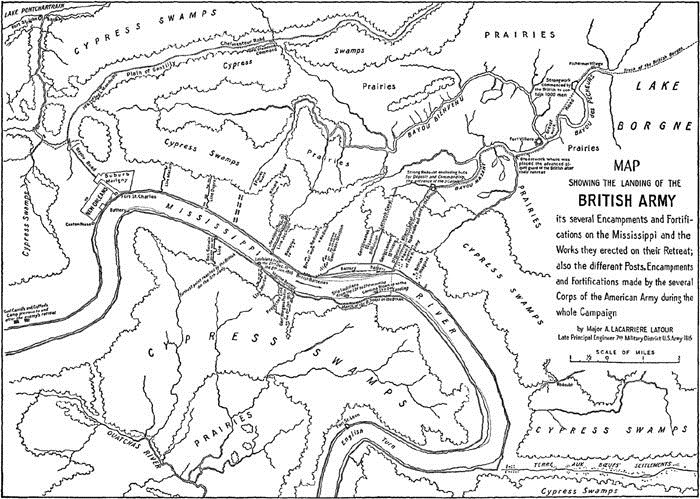

Cochrane, with the division from the Atlantic coast, joined the re-enforcements from England in Negril Bay, and thence proceeded to Mississippi Sound; anchoring off Ship Island, December 8. On the 2d General Jackson had arrived in New Orleans, whither had been ordered a large part of the troops heretofore acting against the Creeks. The British commanders had now determined definitely to attack the city from the side of the sea. As there could be little hope for vessels dependent upon sails to pass the forts on the lower Mississippi, against the strong current, as was done by Farragut's steamers fifty years later, it was decided to reach the river far above those works, passing the army through some of the numerous bayous which intersect the swampy delta to the eastward. From Ship Island this desired approach could be made through Lake Borgne.

For the defence of these waters there were stationed five American gunboats and two or three smaller craft, the whole under command of Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones. As even the lighter British ships of war could not here navigate, on account of the shoalness, and the troops, to reach the place of debarkation, the Bayou des Pêcheurs, at the head of Lake Borgne, must go sixty miles in open boats, the hostile gun vessels had first to be disposed of. Jones, who from an advanced position had been watching the enemy's proceedings in Mississippi Sound, decided December 12 that their numbers had so increased as to make remaining hazardous. He therefore retired, both to secure his retreat and to cause the boats of the fleet a longer and more harassing pull to overtake him. The movement was none too soon, for that night the British barges and armed boats left the fleet in pursuit. Jones was not able to get as far as he wished, on account of failure of wind; but nevertheless on the 13th the enemy did not come up with him. During the night he made an attempt at further withdrawal; but calm continuing, and a strong ebb-tide running, he was compelled again to anchor at 1 A.M. of the 14th, and prepared for battle. His five gunboats, with one light schooner, were ranged in line across the channel way, taking the usual precautions of springs on their cables and boarding nettings triced up. Unluckily for the solidity of his order, the current set two of the gunboats, one being his own, some distance to the eastward,—in advance of the others.

At daylight the British flotilla was seen nine miles distant, at anchor. By Jones' count it comprised forty-two launches and three light gigs.450 They soon after weighed and pulled towards the gunboats. At ten, being within long gunshot, they again anchored for breakfast; after which they once more took to the oars. An hour later they closed with their opponents. The British commander, Captain Lockyer, threw his own boat, together with a half-dozen others, upon Jones' vessel, "Number 156,"451 and carried her after a sharp struggle of about twenty minutes, during which both Lockyer and Jones were severely wounded. Her guns were then turned against her late comrades, in support of the British boarders, and at the end of another half-hour, at 12.40 P.M., the last of them surrendered.

That this affair was very gallantly contested on both sides is sufficiently shown by the extent of the British loss—seventeen killed and seventy-seven wounded.452 They were of course in much larger numbers than the Americans. No such attempt should be made except with this advantage, and the superiority should be as great as is permitted by the force at the disposal of the assailant.

This obstacle to the movement of the troops being removed, debarkation began at the mouth of the Bayou des Pêcheurs;453 whence the British, undiscovered during their progress, succeeded in penetrating by the Bayou Bienvenu and its tributaries to a point on the Mississippi eight miles below New Orleans. The advance corps, sixteen hundred strong, arrived there at noon, December 23, accompanied by Major-General Keane, as yet in command of the whole army. The news reached Jackson two hours later.

Fresh from the experiences of Washington and Baltimore, the British troops flattered themselves with the certainty of a quiet night. The Americans, they said to each other, have never dared to attack. At 7.30, however, a vessel dropped her anchor abreast them, and a voice was heard, "Give them this for the honor of America!" The words were followed by the discharge of her battery, which swept through the camp. Without artillery to reply, having but two light field guns, while the assailant—the naval schooner "Caroline," Lieut. J.D. Henley—had anchored out of musket range, the invaders, suffering heavily, were driven to seek shelter behind the levee, where they lay for nearly an hour.454 At the end of this, a dropping fire was heard from above and inland. Jackson, with sound judgment and characteristic energy, had decided to attack at once, although, by his own report, he could as yet muster only fifteen hundred men, of whom but six hundred were regulars. A confused and desperate night action followed, the men on both sides fighting singly or in groups, ignorant often whether those before them were friends or foes. The Americans eventually withdrew, carrying with them sixty-six prisoners. Their loss in killed and wounded was one hundred and thirty-nine; that of the British, two hundred and thirteen.

The noise of this rencounter hastened the remainder of the British army, and by the night of December 24 the whole were on the ground. Meantime, the "Caroline" had been joined by the ship "Louisiana," which anchored nearly a mile above her. In her came Commodore Patterson, in chief naval command. The presence of the two impelled the enemy to a slight retrograde movement, out of range of their artillery. The next morning, Christmas, Sir Edward Pakenham arrived from England. A personal examination satisfied him that only by a reconnaissance in force could he ascertain the American strength and preparations, and that, as a preliminary to such attempt, the vessels whose guns swept the line of advance must be driven off. On the 26th the "Caroline" tried to get up stream to Jackson's camp, but could not against a strong head wind; and on the 27th the British were able to burn her with hot shot. The "Louisiana" succeeded in shifting her place, and thenceforth lay on the west bank of the stream, abreast of and flanking the entrenchments behind which Jackson was established.

These obstacles gone, Pakenham made his reconnaissance. As described by a participant,455 the British advanced four or five miles on December 28, quite unaware what awaited them, till a turn in the road brought them face to face with Jackson's entrenchments. These covered a front of three fourths of a mile, and neither flank could be turned, because resting either on the river or the swamp. They were not yet complete, but afforded good shelter for riflemen, and had already several cannon in position, while the "Louisiana's" broadside also swept the ground in front. A hot artillery fire opened at once from both ship and works, and when the British infantry advanced they were met equally with musketry. The day's results convinced Pakenham that he must resort to the erection of batteries before attempting an assault; an unfortunate necessity, as the delay not only encouraged the defenders, but allowed time for re-enforcement, and for further development of their preparations. While the British siege pieces were being brought forward, largely from the fleet, a distance of seventy miles, the American Navy was transferring guns from the "Louisiana" to a work on the opposite side of the river, which would flank the enemies' batteries, as well as their columns in case of an attempt to storm.

MAP SHOWING THE LANDING OF THE BRITISH ARMY its several Encampments and Fortifications on the Mississippi and the Works they erected on their Retreat; also the different Posts, Encampments and Fortifications made by the several Corps of the American Army during the whole Campaign by Major A. LACARRIERE LATOUR Late Principal Engineer 7th Military District U.S. Army 1815

When the guns had arrived, the British on the night of December 31 threw up entrenchments, finding convenient material in the sugar hogsheads of the plantations. On the morning of January 1 they opened with thirty pieces at a distance of five hundred yards; but it was soon found that in such a duel they were hopelessly overmatched, a result to which contributed the enfilading position of the naval battery. "To the well-directed exertions from the other side of the river," wrote Jackson to Patterson, after the close of the operations, "must be ascribed in great measure that harassment of the enemy which led to his ignominious flight." The British guns were silenced, and for the moment abandoned; but during the night they were either withdrawn or destroyed. It was thus demonstrated that no adequate antecedent impression could be made on the American lines by cannonade; and, as neither flank could be turned, no resource remained, on the east shore at least, but direct frontal assault.

But while Jackson's main position was thus secure, he ran great risk that the enemy, by crossing the river, and successful advance there, might establish themselves in rear of his works; which, if effected, would put him at the same disadvantage that the naval battery now imposed upon his opponents. His lines would be untenable if his antagonist commanded the water, or gained the naval battery on his flank, to which the crew of the "Louisiana" and her long guns had now been transferred. This the British also perceived, and began to improve a narrow canal which then led from the head of the bayou to the levee, but was passable by canoes only. They expected ultimately to pierce the levee, and launch barges upon the river; but the work was impeded by the nature of the soil, the river fell, and some of the heavier boats grounding delayed the others, so that, at the moment of final assault, only five hundred men had been transported instead of thrice that number, as intended.456 What these few effected showed how real and great was the danger.

The canal was completed on the evening of January 6, on which day the last re-enforcements from England, sixteen hundred men under Major-General Lambert, reached the front. Daylight of January 8 was appointed for the general assault; the intervening day and night being allowed for preparations, and for dragging forward the boats into the river. It was expected that the whole crossing party of fifteen hundred, under Colonel Thornton, would be on the west bank, ready to move forward at the same moment as the principal assault, which was also to be supported by all the available artillery, playing upon the naval battery to keep down its fire. There was therefore no lack of ordinary military prevision; but after waiting until approaching daylight began to throw more light than was wished upon the advance of the columns, Pakenham gave the concerted signal. Owing to the causes mentioned, Thornton had but just landed with his first detachment of five hundred. Eager to seize the battery, from which was to be feared so much destructive effect on the storming columns on the east bank, he pushed forward at once with the men he had, his flank towards the river covered by a division of naval armed boats; "but the ensemble of the general movement," wrote the British general, Lambert, who succeeded Pakenham in command, "was thus lost, and in a point which was of the last importance to the [main] attack on the left bank of the river."