полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

From the 7th to the 11th, the day of the battle, the British were employed in preparations for battering the forts, preliminary to an assault, and there was constant skirmishing at the bridges and fords. Macomb utilized the same time to strengthen his works, aided by the numbers of militia continually arriving, who labored night and day with great spirit. Prevost's purposes and actions were dominated by the urgency of haste, owing to the lateness of the season; and this motive co-operated with a certain captiousness of temper to precipitate him now into a grave error of judgment and of conduct. At Plattsburg he found the small American army intrenched behind a fordable river, the bridges of which had been made useless; and in the bay lay the American squadron, anchored with a view to defence. The two were not strictly in co-operation, in their present position. Tactically, they for the moment contributed little to each other's support; for the reason that the position chosen judiciously by Macdonough for the defence of the bay was too far from the works of the army to receive—or to give—assistance with the guns of that day. The squadron was a little over a mile from the army. It could not remain there, if the British got possession of the works, for it would be within range of injury at long shot; but in an engagement between the hostile fleets the bluffs could have no share, no matter which party held them, for the fire would be as dangerous to friend as to foe.

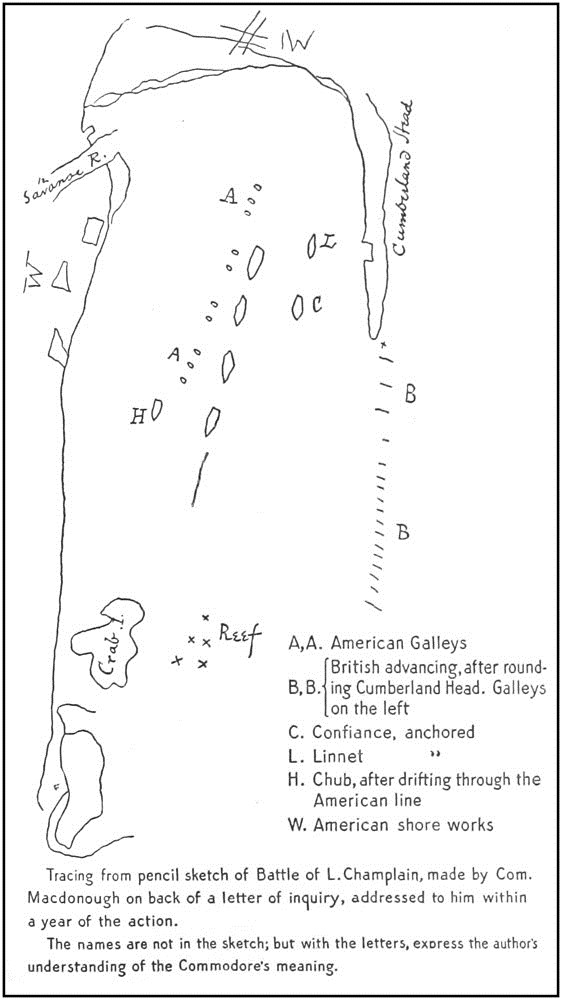

The question of probability, that the American squadron was within long gunshot of the shore batteries, is crucial, for upon it would depend the ultimate military judgment upon the management of Sir George Prevost. That he felt this is evident by letters addressed on his behalf to Macdonough; by A.W. Cochran, a lawyer of Quebec, to whom Prevost, after his recall to England for trial, left the charge of collecting testimony, and by Cadwalader Colden of New York.414 Both inquire specifically as to this distance, Colden particularizing that "it would be all important to learn that the American squadron were during the engagement beyond the effectual range of the batteries." To Colden, Macdonough replied guardedly, "It is my opinion that our squadron was anchored one mile and a half from the batteries." The answer to Cochran has not been found; but on the back of the letter from him the Commodore sketched his recollection of the situation, which is here reproduced. Without insisting unduly on the precision of such a piece, it seems clear that he thought his squadron but little more than half way towards the other side of the bay. Cumberland Head being by survey two miles from the batteries, it would follow that the vessels were a little over a mile from them. This inference is adopted as more dependable than the estimate, "a mile and a half." Such eye reckoning is notoriously uncertain; and this seemingly was made by recollection, not contemporaneously.415

The 24- and 32-pounder long gun of that day ranged a sea mile and a half, with an elevation of less than fifteen degrees.416 They could therefore annoy a squadron at or within that distance. The question is not of best fighting range. It is whether a number of light built and light draught vessels could hold their ground under such a cannonade, knowing that a hostile squadron awaited them without. Even at such random range, a disabling shot in hull or spars must be expected. At whatever risk, departure is enforced.

Tracing from pencil sketch of Battle of L. Champlain, made by Com. Macdonough on back of a letter of inquiry, addressed to him within a year of the action.

The names are not in the sketch; but with the letters, express the author's understanding of the Commodore's meaning.

To a similar letter from Colden, General Macomb replied that he did not think the squadron within range. There is also a statement in Niles' Register417 that several British officers visited Macomb at Plattsburg, and at their request experiments were made, presumably trial shots, to ascertain whether the guns of the forts could have annoyed the American squadron. It was found they could not. Macomb's opinion may have rested upon this, and the conclusion may be just; but it is open to remark that, as the squadron was not then there, its assumed position depended upon memory,—like Macdonough's sketch. Macomb said further, that "a fruitless attempt was made during the action to elevate the guns so as to bear on the enemy; but none were fired, all being convinced that the vessels were beyond their reach." The worth of this conviction is shown by the next remark, which he repeated under date of August 1, 1815.418 "This opinion was strengthened by observations on the actual range of the guns of the 'Confiance'—her heaviest metal [24-pounders] falling upwards of five hundred yards short of the shore." The "Confiance" was five hundred yards further off than the American squadron, and to reach it her guns would be elevated for that distance only. Because under such condition they dropped their shot five hundred yards short of three thousand five hundred yards, it is scarcely legitimate to infer that guns elevated for three thousand could not carry so far.

The arguments having been stated, it is to be remarked that, whatever the truth, it is knowledge after the fact as far as Prevost was concerned. In his report dated September 11, 1814, the day of the action, he speaks of the difficulties which had been before him; among them "blockhouses armed with heavy ordnance." This he then believed; and whether this ordnance could reach the squadron he could only know by trying. It was urgently proper, in view of his large land force, and of the expectations of his Government, which had made such great exertions for an attainable and important object, that he should storm the works and try. After a careful estimate of the strength of the two squadrons, I think that a seaman would certainly say that in the open the British was superior; but decidedly inferior for an attack upon the American at anchor. This was the opinion of the surviving British officers, under oath, and of Downie. General Izard, who had been in command at Plattsburg up to a fortnight before the attack, wrote afterwards to the Secretary of War, "I may venture to assert that without the works, Fort Moreau and its dependencies, Captain Macdonough would not have ventured to await the enemy's attack in Plattsburg Bay, but would have retired to the upper part of Lake Champlain."419 The whole campaign turning upon naval control, the situation was eminently one that called upon the army to drive the enemy from his anchorage. The judgment of the author endorses the words of Sir James Yeo: "There was not the least necessity for our squadron giving the enemy such decided advantages by going into their bay to engage them. Even had they been successful, it could not in the least have assisted the troops in storming the batteries; whereas, had our troops taken their batteries first, it would have obliged the enemy's squadron to quit the bay and given ours a fair chance."420 At the Court Martial two witnesses, Lieutenant Drew of the "Linnet," and Brydone, master of the "Confiance," swore that after the action Macdonough removed his squadron to Crab Island, out of range of the batteries. Macdonough in his report does not mention this; nor was it necessary that he should.

In short, though apparently so near, the two fractions of the American force, the army and the navy, were actually in the dangerous military condition of being exposed to be beaten in detail; and the destruction of either would probably be fatal to the other. The largest two British vessels, "Confiance" and "Linnet," were slightly inferior to the American "Saratoga" and "Eagle" in aggregate weight of broadside; but, like the "General Pike" on Ontario in 1813, the superiority of the "Confiance" in long guns, and under one captain, would on the open lake have made her practically equal to cope with the whole American squadron, and still more with the "Saratoga" alone, assuming that the "Linnet" gave the "Eagle" some occupation.

It would seem clear, therefore, that the true combination for the British general would have been to use his military superiority, vast in quality as in numbers, to reduce the works and garrison at Plattsburg. That accomplished, the squadron would be driven to the open lake, where the "Confiance" could bring into play her real superiority, instead of being compelled to sacrifice it by attacking vessels in a carefully chosen position, ranged with a seaman's eye for defence, and prepared with a seaman's foresight for every contingency. Prevost, however, became possessed with the idea that a joint attack was indispensable,421 and in communicating his purpose to the commander of the squadron, Captain Downie, he used language indefensible in itself, tending to goad a sensitive man into action contrary to his better judgment; and he clenched this injudicious proceeding with words which certainly implied an assurance of assault by the army on the works, simultaneous with that of the navy on the squadron.

Captain Downie had taken command of the Champlain fleet only on September 2. He was next in rank to Yeo on the lakes, a circumstance that warranted his orders; the immediate reason for which, however, as explained by Yeo to the Admiralty, was that his predecessor's temper had shown him unfit for chief command. He had quarrelled with Pring, and Yeo felt the change essential. Downie, upon arrival, found the "Confiance" in a very incomplete state, for which he at least was in no wise responsible. He had brought with him a first lieutenant in whom he had merited confidence, and the two worked diligently to get her into shape. The crew had been assembled hurriedly by draughts from several ships at Quebec, from the 39th regiment, and from the marine artillery. The last detachment came on board the night but one before the battle. They thus were unknown by face to their officers, and largely to one another. Launched August 25, the ship hauled from the wharf into the stream September 7, and the same day started for the front, being towed by boats against a head wind and downward current. Behind her dragged a batteau carrying her powder, while her magazine was being finished.

The next day a similar painful advance was made, and the crew then were stationed at the guns, while the mechanics labored at their fittings. That night she anchored off Chazy, where the whole squadron was now gathered. The 9th was spent at anchor, exercising the guns; the mechanics still at work. In fact, the hammering and driving continued until two hours before the ship came under fire, when the last gang shoved off, leaving her still unfinished. "This day"—the 9th—wrote the first lieutenant, Robertson, "employed setting-up rigging, scraping decks, manning and arranging the gunboats. Exercised at great guns. Artificers employed fitting beds, coins, belaying pins, etc;"422—essentials for fighting the guns and working the sails. It scarcely needs the habit of a naval seaman to recognize that even three or four days' grace for preparation would immensely increase efficiency. Nevertheless, such was the pressure from without that the order was given for the squadron to go into action next day; and this was prevented only by a strong head wind, against which there was not channel space to beat.

As long as Prevost was contending with the difficulties of his own advance he seems not to have worried Downie; but as soon as fairly before the works of Plattsburg he initiated a correspondence, which on his part became increasingly peremptory. It will be remembered that he not only was much the senior in rank,—as in years,—but also Governor-General of Canada. Nor should it be forgotten that he had known and written a month before that the "Confiance" could not be ready before September 15. He knew, as his subsequent action showed, that if the British fleet were disabled his own progress was hopeless; and, if he could not understand that to a ship so lately afloat a day was worth a week of ordinary conditions, he should at least have realized that the naval captain could judge better than he when she was ready for battle. On September 7 he wrote to urge Downie, who replied the same day with assurances of every exertion to hasten matters. The 8th he sent information of Macdonough's arrangements by an aid, who carried also a letter saying that "it is of the highest importance that the ships, vessels, and gunboats, under your command, should combine a co-operation with the division of the army under my command. I only wait for your arrival to proceed against General Macomb's last position on the south bank of the Saranac." On the 9th he wrote, "In consequence of your communication of yesterday I have postponed action until your squadron is prepared to co-operate. I need not dwell with you on the evils resulting to both services from delay." He inclosed reports received from deserters that the American fleet was insufficiently manned; and that when the "Eagle" arrived, a few days before, they had swept the guard houses of prisoners to complete her crew. A postscript conveyed a scarcely veiled intimation that an eye was kept on his proceedings. "Captain Watson of the provincial cavalry is directed to remain at Little Chazy until you are preparing to get underway, when he is instructed to return to this place with the intelligence."423

Thus pressed, Downie, as has been said, gave orders to sail at midnight, with the expectation of rounding into Plattsburg Bay about dawn, and proceeding to an immediate attack. This purpose was communicated formally to Prevost. The preventing cause, the head wind, was obvious enough, and spoke for itself; but the check drew from Prevost words which stung Downie to the quick. "In consequence of your letter the troops have been held in readiness, since six o'clock this morning, to storm the enemy's works at nearly the same moment as the naval action begins in the bay. I ascribe the disappointment I have experienced to the unfortunate change of wind, and shall rejoice to learn that my reasonable expectations have been frustrated by no other cause." The letter was sent by the aid, Major Coore, who had carried the others; and both he and Pring, who were present, testified to the effect upon Downie. Coore, in a vindication of Prevost, wrote, "After perusing it, Captain Downie said with some warmth, 'I am surprised Sir George Prevost should think necessary to urge me upon this subject. He must feel I am as desirous of proceeding to active operations as he can be; but I am responsible for the squadron, and no man shall make me lead it into action before I consider it in fit condition.'"424 Nevertheless, the effect was produced; for he remarked afterward to Pring, "This letter does not deserve an answer, but I will convince him that the naval force will not be backward in their share of the attack."425

It was arranged that the approach of the squadron should be signalled by scaling the guns,—firing cartridges without shot; and Downie certainty understood, and informed his officers generally, that the army would assault in co-operation with the attack of the fleet. The precise nature of his expectation was clearly conveyed to Pring, who had represented the gravity of this undertaking. "When the batteries are stormed and taken possession of by the British land forces, which the commander of the land forces has promised to do at the moment the naval action commences, the enemy will be obliged to quit their position, whereby we shall obtain decided advantage over them during their confusion. I would otherwise prefer fighting them on the lake, and would wait until our force is in an efficient state; but I fear they would take shelter up the lake and would not meet me on equal terms."426 The following morning, September 11, the wind being fair from northeast, the British fleet weighed before daylight and stood up the narrows for the open lake and Plattsburg Bay. About five o'clock the agreed signal was given by scaling the guns, the reports of which it was presumed must certainly be heard by the army at the then distance of six or seven miles, with the favorable air blowing. At 7.30, near Cumberland Head, the squadron hove-to, and Captain Downie went ahead in a boat to reconnoitre the American position.

For defence against the hostile squadron, Macdonough had had to rely solely on his own force, and its wise disposition by him. On shore, a defensive position is determined by the circumstances of the ground selected, improved by fortification; all which gives strength additional to the number of men. A sailing squadron anchored for defence similarly gained force by adapting its formation to the circumstances of the anchorage, and to known wind conditions, with careful preparations to turn the guns in any direction; deliberate precautions, not possible to the same extent to the assailant anchoring under fire. To this is to be added the release of the crew from working sails to manning the guns.

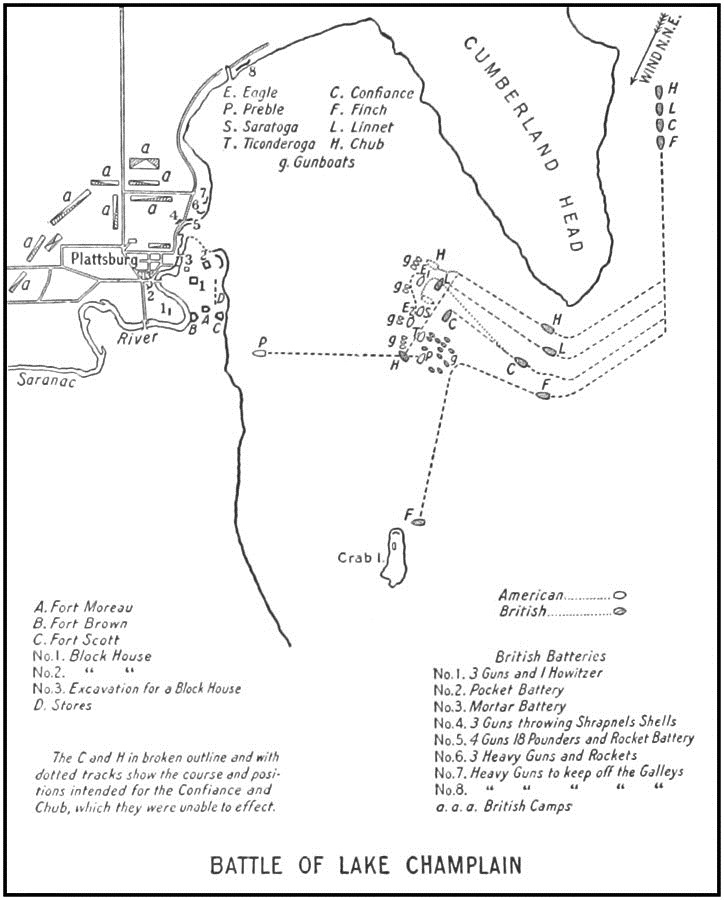

Plattsburg Bay, in which the United States squadron was anchored, is two miles wide, and two long. It lies north and south, open to the southward. Its eastern boundary is called Cumberland Head. The British vessels, starting from below, in a channel too narrow to beat, must come up with a north wind. To insure that this should be ahead, or bring them close on the wind, after rounding the Head,—a condition unfavorable for attack,—Macdonough fixed the head of his line as far north as was safe; having in mind that the enemy might bring guns to the shore north of the Saranac. His order thence extended southward, abreast of the American works, and somewhat nearer the Cumberland than the Plattsburg side. The wind conditions further made it expedient to put the strongest vessels to the northward,—to windward,—whence they would best be able to manœuvre as circumstances might require. The order from north to south therefore was: the brig "Eagle," twenty guns; the ship "Saratoga," twenty-six; the "Ticonderoga" schooner, seven, and the sloop "Preble," seven.

Macdonough's dispositions being perfectly under observation, Captain Downie framed his plan accordingly.427 The "Confiance" should engage the "Saratoga;" but, before doing so, would pass along the "Eagle," from north to south, give her a broadside, and then anchor head and stern across the bows of the "Saratoga." After this, the "Linnet," supported by the "Chub," would become the opponent of the "Eagle," reduced more nearly to equality by the punishment already received. Three British vessels would thus grapple the two strongest enemies. The "Finch" was to attack the American rear, supported by all the British gunboats—eleven in number. There were American gunboats, or galleys, as well, which Macdonough distributed in groups, inshore of his order; but, as was almost invariably the case, these light vessels exerted no influence on the result.

This being the plan, when the wind came northeast on the morning of September 11, the British stood up the lake in column, as follows: "Finch," "Confiance," "Linnet," "Chub." Thus, when they rounded Cumberland Head, and simultaneously changed course towards the American line, they would be properly disposed to reach the several places assigned. As the vessels came round the Head, to Downie's dismay no co-operation by the army was visible. He was fairly committed to his movement, however, and could only persist. As the initial act was to be the attack upon the "Eagle" by the "Confiance," she led in advance of her consorts, which caused a concentration of the hostile guns upon her; the result being that she was unable to carry out her part. The wind also failed, and she eventually anchored five hundred yards from the American line. Her first broadside is said to have struck down forty, or one fifth of the "Saratoga's" crew. As in the case of the "Chesapeake," this shows men of naval training, accustomed to guns; but, as with the "Chesapeake," lack of organization, of the habit of working together, officers and men, was to tell ere the end. Fifteen minutes after the action began Captain Downie was killed, leaving in command Lieutenant Robertson.

BATTLE OF LAKE CHAMPLAIN

The "Linnet" reached her berth and engaged the "Eagle" closely; but the "Chub," which was to support her, received much damage to her sails and rigging, and the lieutenant in charge was nervously prostrated by a not very severe wound. Instead of anchoring, she was permitted to drift helplessly, and so passed through the American order, where she hauled down her colors. Though thus disappointed of the assistance intended for her, the "Linnet" continued to fight manfully and successfully, her opponent finally quitting the line; a result to which the forward battery of the "Confiance" in large measure contributed.428 The "Finch," by an error of judgment on the part of her commander, did not keep near enough to the wind. She therefore failed to reach her position, near the "Ticonderoga;" and the breeze afterwards falling, she could not retrieve her error. Ultimately, she went ashore on Crab Island, a mile to the southward. This remoteness enabled her to keep her flag flying till her consorts had surrendered; but the credit of being last to strike belongs really to the "Linnet," Captain Pring. By the failure of the "Finch," the "Ticonderoga" underwent no attack except by the British gunboats. Whatever might possibly have come of this was frustrated by the misbehavior of most of them. Four fought with great gallantry and persistence, eliciting much admiration from their opponents; but the remainder kept at distance, the commander of the whole actually running away, and absconding afterwards to avoid trial. The "Ticonderoga" maintained her position to the end; but the weak "Preble" was forced from her anchors, and ran ashore under the Plattsburg batteries.

The fight thus resolved itself into a contest between the "Saratoga" and "Eagle," on one side, the "Confiance" and "Linnet" on the other. The wind being north-northeast, the ships at their anchors headed so that the forward third of the "Confiance's" battery bore upon the "Eagle," and only the remaining two thirds upon the "Saratoga." This much equalized conditions all round. It was nine o'clock when she anchored. At 10.30 the "Eagle," having many of her guns on the engaged side disabled, cut her cable, ran down the line, and placed herself south of the "Saratoga," anchoring by the stern. This had the effect of turning towards the enemy her other side, the guns of which were still uninjured. "In this new position," wrote Lieutenant Robertson, "she kept up a destructive fire on the "Confiance," without being exposed to a shot from that ship or the "Linnet." On the other hand, Macdonough found the "Saratoga" suffer from the "Linnet," now relieved of her immediate opponent."429

By this time the fire of both the "Saratoga" and "Confiance" had materially slackened, owing to the havoc among guns and men. Nearly the whole battery on the starboard side of the United States ship was dismounted, or otherwise unserviceable. The only resource was to bring the uninjured side towards the enemy, as the "Eagle" had just done; but to use the same method, getting under way, would be to abandon the fight, for there was not astern another position of usefulness for the "Saratoga." There was nothing for it but to "wind"430 the ship—turn her round where she was. Then appeared the advantage attendant upon the defensive, if deliberately utilized. The "Confiance" standing in had had shot away, one after another, the anchors and ropes upon which she depended for such a manœuvre.431 The "Saratoga's" resources were unimpaired. A stern anchor was let go, the bow cable cut, and the ship winded, either by force of the wind, or by the use of "springs"432 before prepared, presenting to the "Confiance" her uninjured broadside—for fighting purposes a new vessel. The British ship, having now but four guns that could be used on the side engaged,433 must do the like, or be hopelessly overmatched. The stern anchor prepared having been shot away, an effort was made to swing her by a new spring on the bow cable; but while this slow process was carrying on, and the ship so far turned as to be at right angles with the American line, a raking shot entered, killing and wounding several of the crew. Then, reported Lieutenant Robertson, the surviving officer in command, "the ship's company declared they would stand no longer to their quarters, nor could the officers with their utmost exertions rally them." The vessel was in a sinking condition, kept afloat by giving her a marked heel to starboard, by running in the guns on the port side, so as to bring the shot holes out of water.434 The wounded on the deck below had to be continually moved, lest they should be drowned where they lay. She drew but eight and a half feet of water. Her colors were struck at about 11 A.M.; the "Linnet's" fifteen minutes later. By Macdonough's report, the action had lasted two hours and twenty minutes, without intermission.