полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

If the specimen referred to in the foot-note at the beginning of this article as collected by Mr. Allen on Mount Lincoln be really this species, an important advance in its history will have been reached, showing that their summers are spent in the high mountain summits, and that the rest of the year is passed lower down on the plains.

Leucosticte tephrocotis, var. campestris, BairdTHE GRAY-CHEEKED FINCHLeucosticte campestris, Baird, Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 163, 1870.

Sp. Char. Body light chocolate-brown, the feathers edged with paler, those of the back with rather darker centres. Feathers of anal region, flanks behind, crissum, rump, and upper tail-coverts, wing-coverts, and primary quills, edged with rose-red; secondary quills and tail-feathers with pale fulvous; little or no trace of rose on under wings. Forehead and patch on crown blackish; the hind head to nape, cheeks immediately under the eye (but not including the auriculars, except, perhaps, the most anterior) and base of lower mandible all round, ashy-gray. Throat dusky. Bill yellowish, with dusky tip. Legs dusky.

No. 41,527, near Denver City, Col., January, 1862 (Dr. C. Wernigk). Length, 7.00; wing, 4.00; tail, 3.00; exposed portion of first primary, 3.10. Bill from forehead, .60; from nostril, .40; tarsus, .75; middle toe and claw, .80; claw alone .24; hind toe and claw, .80; claw alone, .37.

Hab. Colorado Territory (Dr. Wernigk); Wyoming Territory (Mr. H. R. Durkee).

This form bears a close resemblance to L. tephrocotis, and may, indeed, be a variety of it; but as it differs in the characters that appear generally to be those most constant in Leucosticte, and as, in fifty skins of the tephrocotis from one locality, we have seen nothing like it, we are inclined to consider them distinct. The size and general appearance are much the same, the difference being that in tephrocotis the whole cheeks are chocolate below the level of the eye, the chin without any gray; while in campestris the sides of head below the eye, but not including the ears, with a narrow border of the chin, are of this color.

From littoralis this form may be distinguished by the less extent of ash on the cheeks, which in littoralis covers the whole ears, and extends back farther on the head all round. L. griseinucha is marked like littoralis, and is much larger than either. Possibly it may be well to entertain the idea of its being a hybrid between tephrocotis and littoralis or griseinucha.

The specimen described was presented to the Smithsonian Institution by Dr. Wernigk, and at the time was supposed to be L. tephrocotis.

Of this form, nothing as to its habits is known with certainty. It probably does not differ in any important respect from the allied races.

Leucosticte tephrocotis, var. littoralis, BairdHEPBURN’S FINCHLeucosticte griseinucha, Elliot, Illust. Birds Am. X. Leucosticte littoralis, Baird, Tr. Ch. A. S. I, 1869, 318, pl. xxviii, f. 1.—Dall & Bannister, Ib. p. 282.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 162.

Sp. Char. Body chocolate-brown, the feathers narrowly margined with paler, those of the back with rather darker centres. Abdomen, flanks, crissum, rump, upper tail-coverts, wing-coverts, and quills edged with rose-red, more or less continuous (least so on the rump); the outer edges of secondaries and tail-feathers pale fulvous, the latter with a rosy shade. Head silvery-gray; the forehead and patch on crown black; the chin gray, continuous with that of cheek; the throat dark brown, shading into the chocolate of breast. Bill yellowish, the extreme tip dusky. Nasal feathers white. Length, 7.10; wing. 4.30; tail, 3.10; exposed portion of first primary, 3.40. Length of bill from forehead, .60; from nostril, .35. Tarsus, .76.

Hab. Kodiak (Bischoff); Sitka (Bischoff); Fort Simpson, British Columbia (Hepburn); Gilmer, Wyoming (Durkee).

This race, which we believe to be the Southern coast representative of griseinucha, bears much resemblance to that bird, but is considerably smaller; the colors are brighter and lighter, more like those of tephrocotis, and the bill is shorter and more conical, the dark patch on the head more restricted, the chin more ashy, and the brown of the head not so far forward. From tephrocotis it is distinguished by the extension of the ash of head below the eye; and from campestris by having the ear-coverts ashy, instead of the anterior portion of the cheeks only; and there is apparently a greater extent of gray on the chin.

Specimens obtained at Kodiak in February are distinguishable from specimens of griseinucha, obtained with them at the same place, only by their much smaller size, and lighter chocolate tints. The occurrence of both these races at the same place, at the same time, is a subject for speculation. A perfectly typical specimen (No. 59,906) is in the collection from Gilmer, Wyoming Territory, obtained by Mr. H. R. Durkee, a frequent contributor to the collections of the Smithsonian Institution, and sent by him along with numerous specimens of L. tephrocotis, with which it appears to have been mixed.

Leucosticte tephrocotis, var. griseinucha, BairdTHE GRAY-EARED FINCHPasser arctous, var. γ, Pallas, Zoög. Rosso-Asiat. II (1831), 23. Fringilla (Linaria) griseinucha, Brandt, Bull. Acad. St. Petersburg, Nov. 1841, 36. Montifringilla (Leucosticte) griseinucha, Bon. & Schl. Mon. Loxiens (1850), 35, pl. xli. Leucosticte griseinucha, Baird, Birds N. Am. 430.—Kittlitz, Denkwürdigkeiten (1858), I, 291.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. Ac. Sc. I, 1869, 282.—Baird, Ib. p. 317, pl. xxviii, f. 2.—Elliot, Illust. Am. B. pl. xi.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 161. Leucosticte griseigenys, Gould, Voy. Sulphur.

Sp. Char. Description of specimen No. 54,246: General color dark brownish-chocolate anteriorly, the feathers of back rather darker in the centre, and with paler edges. Forehead and crown black; rest of the head, including the cheeks and ears, of a rather silvery gray; throat blackish, shading off insensibly into the chocolate of breast. Feathers of abdomen (and hinder part of breast to a less degree), flanks and crissum, with the rump and upper tail-coverts, and lesser and middle wing-coverts, tipped with dark pomegranate or rose-red, allowing more or less of thin dusky bases to be seen, especially above, where there is an appearance of bars. Wing and tail feathers brown, nearly all, including the greater wing-coverts, edged with pale yellowish-gray with only a faint tinge of rose. Bill dusky; darkest at tip. Legs black.

Dimensions: Total length, 7.50; wing, 4.80; tail, 3.50. Exposed portion of first primary, 3.50. Bill, from forehead, .69; from nostril, .42. Legs: tarsus, .95; middle toe and claw, .92; claw alone, .35; hind toe and claw, .69; claw alone, .38.

Hab. Aleutian Islands (St. George’s and Unalaschka).

This is considerably the largest of the American species of Leucosticte, and has a longer bill. It also has the chocolate and rose color darker, and the rose extending farther forward on the breast than in other species. It could only be confounded with C. littoralis as to color, both having the head above, and on the sides, ashy, covering the whole ear-coverts; but the dusky patch on the crown is more extended, the ash of chin more restricted, and the throat darker. The rose extends farther along the breast, and the tints are different. The size is much larger.

A specimen, apparently young, perhaps a female, differs in duller tints, and a tinge of ochreous-yellow on the middle of the abdomen and crissum. The lining of the wings is without any rose-color.

Bonaparte and Schlegel describe the young of this species as without rose-color.

Specimens of this bird were obtained at St. George’s Island, with the eggs (which are white), by Mr. W. H. Dall. Dr. Minor found it at Unalaschka.

Habits. The Gray-eared Finch is the largest species of this remarkable genus known to inhabit North America. Thus far, except in one instance, it has been met with only in the Aleutian Islands and Unalaschka. In the latter place they were met with by Dr. T. T. Minor, and in the former by Mr. Dall.

Mr. R. Brown (Ibis, 1868, p. 432) states that a single specimen of this very rare bird was taken at Fort Rupert, Vancouver Island, in June, 1862, by Mr. P. M. Compton, the officer in charge of that station. This, however, may have belonged to the var. littoralis.

Mr. Dall states that they abound on the Pribylow and the other Aleutian Islands. A number of specimens were obtained on the St. George’s in August, though at that time they were moulting. At that season this bird had no song except a clear chirp, sounding like wéet-a wèet-a-wée-weet. It was on the wing a great part of the time, rarely alighting on the ground, but darting rapidly in a series of descending and ascending curves. At one time it would swing on the broad top of an umbelliferous plant, and at another alight on some ledge of the perpendicular bluff, jumping from point to point, as if delighting to test its own agility. Mr. Dall adds that its nest is a simple hollow on one of the ledges, provided with a few straws or a bit of moss. They deposit their eggs in May, and these are four in number. In August their young were fully fledged.

They feed on the seeds of grasses and other small plants, but in the crop of one Mr. Dall found two or three small beetles. They were also received from Kodiak, through Mr. Bischoff.

Their eggs are of a grayish-white, with a slight tinge of yellowish, and measure .95 by .70 of an inch.

Genus PLECTROPHANES, MeyerPlectrophanes, Meyer, “Taschenbuch, 1810.” Agassiz. (Type, Emberiza nivalis.)

Centrophanes, Kaup, “Entw. Gesch. Europ. Thierwelt, 1829.” Agassiz. (Type, E. lapponica.)

Gen. Char. Bill variable; conical; the lower mandible higher than the upper; the sides of both mandibles (in the typical species) guarded by a closely applied brush of stiffened bristly feathers directed forwards, and in the upper jaw concealing the nostrils; the outlines of the bill nearly straight, or slightly curved; the lower jaw considerably broader at the base than the upper, and wider than the gonys is long. Tarsi considerably longer than the middle toe; the lateral toes nearly equal (the inner claw largest), and reaching to the base of the middle claw. The hinder claw very long, moderately curved and acute, considerably longer than its toe; the toe and claw together reaching to the middle of the middle claw, or beyond its tip. Wings very long and much pointed, reaching nearly to the end of the tail; the first quill longest; the others rapidly graduated; the tertiaries a little longer than the secondaries. Tail moderate, about two thirds as long as the wings; nearly even, or slightly emarginated.

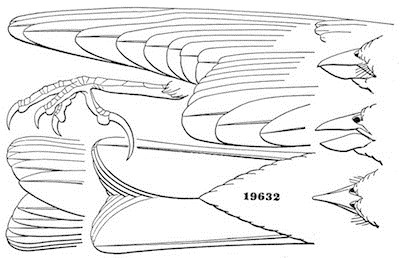

Plectrophanes nivalis.

19632

Plectrophanes nivalis.

The species of this genus are essentially boreal and cosmopolitan, although America possesses four species not found, like her two others, in the Old World. They are all ground-birds, collecting in large flocks, in autumn and winter, on prairies and plains, some of the species passing far to the southward. There is much variation in the color, and in the details of structure of bill and feet. In P. nivalis alone is the fringe of bristly feathers along the side of the bill very distinct. The gonys also is exceptionally short, being less than half the length of the culmen.

The females are less strongly marked than the males, lacking the distinct patches of black (which, however, are nearly always faintly indicated), and other characters, and are streaked like the Spizellinæ.

Species and VarietiesA. Prevailing color white.

1. P. nivalis. ♂. Back, scapulars, ends of tertials, alula, terminal half of primaries and the middle tail-feathers, deep black; otherwise pure white. ♀. The black replaced by grayish with black spots; crown grayish spotted with black. Young considerably tinged with ochraceous. Hab. Circumpolar regions; south in winter into the United States.

B. Above brown, spotted with black. ♂. Crown black.

a. Six to ten middle tail-feathers almost wholly black; the rest without black ends. ♂ with a nuchal collar of rufous or buff, and without rufous on the wings.

2. P. lapponicus. ♂. Head, all round, and jugulum, deep black; a post-ocular stripe, running downward behind the black jugular patch, and entire lower parts from the jugulum, white. Nuchal collar chestnut-rufous. ♀ with the black areas merely indicated by a dusky clouding, and merely a tinge of rufous round the nape. Hab. Circumpolar regions; south in winter into the United States.

3. P. pictus. ♂. Head above and laterally deep black, bordered anteriorly and below with white; a post-ocular stripe, and an ovate auricular spot of the same. Nuchal collar and entire lower surface bright buff. ♀. Pale grayish-buff, darker above; above distinctly, and on the jugulum obsoletely, streaked with black. Hab. Interior plains of North America, north to Arctic Ocean.

4. P. ornatus. ♂ Head above, and whole breast and abdomen, black; a superciliary stripe, side of head, chin, throat, anal region and crissum, white; nuchal collar rufous. ♀ hardly distinguishable from that of P. pictus.

a. Lesser wing-coverts brownish-gray; black feathers of breast, etc., without rufous edges. Hab. Interior plains of United States. … var. ornatus.

b. Lesser wing-coverts black; black feathers of breast, etc., with rufous edges. Hab. Southern plains of North America, and table-land of Mexico … var. melanomus.

b. Only two middle tail-feathers almost wholly black; the rest with black ends. ♂ without a nuchal collar of rufous or buff, and with rufous on the wings.

5. P. maccowni. ♂. Crown, and a broad crescent on the jugulum, black; rest of head and neck ashy, approaching white on the throat and over the eye; beneath white, above grayish-brown, streaked with black; middle wing-coverts rufous. ♀. Above yellowish-umber, beneath yellowish-white; thickly streaked above, unstreaked beneath. No rufous on wings, and no black on head or jugulum. Hab. Plains, from Texas, northward.

There seems to be no special reason for subdividing this genus, although this has been done,—P. nivalis being alone retained in Plectrophanes; P. maccowni forming the type and sole member of the genus Rhyncophanes (Baird, 1858), and the rest coming under Centrophanes (Kaup). The characters upon which these are based are very trivial, being mainly the varying degree of size of the bill and length of the hind claw. In this latter respect there is too much individual variation in the same species to admit of this being available as a specific, much less as a subgeneric character, while the size of the bill is not of more than specific importance.

Plectrophanes nivalis, MeyerSNOW-BUNTINGEmberiza nivalis, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 308 (not Fringilla nivalis, L.).—Forster, Phila. Trans. LXII, 1772, 403.—Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 86, pl. xxi.—Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 1834, 575; V, 1839, 496, pl. 189. Emberiza (Plectrophanes) nivalis, Bon. Obs. 1825, No. 89. “Plectrophanes nivalis, Meyer.”—Bon. List, 1838.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 103.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 55, pl. 155.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 1858, 345 (Spitzbergen).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 432.—Newton, Ibis, 1865, 502.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. A. S. I, 1869, 282 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 177.—Samuels, 296. Emberiza montana, Gmelin, Syst. I, 1788, 867, 25. Emberiza mustelina, Gmelin, Syst. I, 1788, 867, 7. Emberiza glacialis, Latham, Ind. Orn. I, 1790, 398.

Sp. Char. Male. Colors, in spring plumage, entirely black and white. Middle of back between scapulars, terminal half of primaries and tertiaries, and two innermost tail-feathers, black; elsewhere pure white. Legs black at all seasons. In winter dress white beneath; the head and rump yellowish-brown, as also some blotches on the side of the breast; middle of back brown, streaked with black; white on wings and tail much more restricted. Length about 6.75; wings, 4.35; tail, 3.05; first quill longest. Female. Spring, continuous white beneath only; above entirely streaked, the feathers having blackish centres and whitish edges; the black streaks predominate on the back and crown. Young. Light gray above with obsolete dusky streaks on the back; throat and jugulum paler gray, the latter with obsolete streaks; rest of lower parts dull white. Wing-coverts, secondaries, and tail-feathers broadly edged with light ochraceous-brown.

Hab. Northern America from Atlantic to Pacific; south into the United States in winter, as far as Georgia and Southern Illinois.

Specimens from North America and Europe appear to be quite identical; there is, however, a great amount of variation among individuals.

Habits. The common Snow Bunting is found throughout northern North America to the shores of the Arctic Sea, and in the winter months extends its migrations into the United States as indicated above.

Mr. Dall states that in Alaska, when observed, they went altogether in flocks. It was at times excessively common, and at others entirely absent. It builds its nests on the hillside, generally on the ground, under the lee of a stone. He obtained a large number of these birds at Nulato, in the winter of 1867-68. It was much more common there than the P. lapponicus, which was only seen in the spring, while this bird was there all the year round. Mr. Dall also met with these birds on St. George’s Island, and Mr. Bischoff obtained them at Sitka. According to Mr. Bannister’s observations it was altogether less abundant than the P. lapponicus, and seemed to prefer rather different situations. On St. Michael’s Island he never saw one of this species far from the shore, while the other species was abundant everywhere in the interior of the island. During the summer he never saw more than one or two of these birds at once, nor anywhere except on rocky points or on small rocky islands near the shore. These localities they seemed to share with the Ravens and Puffins. In the autumn they are more gregarious, but still seem to prefer the vicinity of water. Mr. Bannister also observed this bird at Unalaklik, where it is common.

Wilson was of the opinion that these birds derive a considerable part of their food from the seeds of certain aquatic plants, and this he supposed one of the principal reasons why they prefer remote northern regions intersected with streams, ponds, lakes, and arms of the sea, abounding with such plants. On Seneca River, near Lake Ontario, in October, he met with a large flock feeding on the surface of the water, supported on the close tops of weeds that rose from the bottom. They were running about with great activity, and the stomachs of those he shot were filled not only with the seeds of that plant, but also with minute shell-fish that adhered to the leaves.

Richardson states that this species breeds in the most northern of our Arctic islands, and on all the shores of the continent, from Chesterfield’s Inlet to Behring Strait. The most southerly of its breeding-places known to him was Southampton Island, in the 62d parallel, where Captain Lyons found a nest on the grave of an Esquimaux child. Its nest was usually made of dry grass, neatly lined with deer’s hair and a few feathers, and is generally fixed in the crevice of a rock, or in a loose pile of timbers or stones. The eggs are described as of a greenish-white, with a circle of irregular umber-brown spots round the larger end, with numerous blotches of subdued lavender-purple. July 22, in removing some drift timber on a beach at Cape Parry, he discovered a nest on the ground, containing four young Snowbirds. Care was taken not to injure them, and while they were seated at breakfast, at a distance of only two or three feet, the parent birds made frequent visits to their offspring, each time bringing grubs in their bills. The Snowbirds are in no apparent haste to leave for the South on the approach of winter, but linger about the forts and open places, picking up seeds, until the snow becomes too deep. It is not until December or January that they retire to the south of the Saskatchewan. It returns to that river about the middle of February, by April it has reached the 65th parallel, and by the beginning of May it is found on the shores of the Polar Sea. At this period it feeds on the buds of the Saxifraga oppositifolia, one of the earliest of the Arctic plants. The young are fed with insects.

The Snow Bunting is also an inhabitant, during the breeding-season, of the Arctic regions of Europe and Asia, and the islands of the Arctic Sea. Scoresby states that it resorts in large flocks to the shores of Spitzbergen, and Captain Sabine includes it among the birds of Greenland and the North Georgian Islands, where it is among the earliest arrivals. Mr. Proctor, who visited Iceland in 1837, found the Snowbird breeding there in June. He found their nests placed among large stones or in the fissures of rocks, composed of dry grass lined with hair and feathers. The eggs were from four to six in number. The male attends the female during incubation. Mr. Proctor states that he has seen this bird, when coming from the nest, rise up in the air and sing sweetly, with its wings and tail spread in the manner of the Tree Pipit. Linnæus, in his Tour in Lapland, mentions seeing these birds in that country about the end of May, and also in July. He also mentions that this bird is the only living thing that has been seen two thousand feet above the line of perpetual snow in the Lapland Alps. This bird also breeds on the Faroe Islands. Mr. Hewitson found its nest in Norway. It contained young, and was built under some loose stones. Young birds have also been noticed early in August among the Grampians, in Scotland, rendering it probable that they breed in that locality, and perhaps in considerable numbers. As the severity of winter increases, they leave the heaths where they have fed upon the seeds of grasses, and descend to the lowlands, frequenting the oat-stubbles, and, when the snow is deep, approaching the coast. Their call-note is pleasing, and is often repeated during their flight, which they make in a very compact body. Before settling on the ground they make sudden wheels, coming almost into collision with each other, uttering at the same time a peculiar guttural note. They run on the ground with all the ease of Larks, and rarely perch. Temminck states that they are very abundant in winter along the sea-coast of Holland.

Their appearance in Massachusetts is usually with the first heavy falls of snow, in December and January. They are most abundant in the open places near the sea-coast, and formerly were very numerous in the marshes between Boston and Brookline. A wounded male in full adult plumage was taken by me, in 1838, and kept some time in confinement. It would not accustom itself to a cage, and a large box was prepared in which it could run more at large. It fed readily on grain and cracked corn, delighted to bathe itself several times in the day, but would not be reconciled to my near presence. On my approach it would rush about its prison, uttering its peculiar call-notes, blending with them a loud guttural cry of alarm. As the spring approached, it warbled occasionally a few notes, but uttered from time to time such mournful cries, as if bewailing its captivity, that it would have been released, had its crippled condition permitted it to take care of itself. It was given in charge of a friend, but did not live through the heat of the ensuing summer.

It is stated that a nest of this bird was found among the White Mountains by Mr. Kirk Boott, of Boston, in the summer of 1834. It contained young birds. This, if the identification was correct, was probably an accidental occurrence. None have been noticed there since, nor have I ever been able to find any of the permanent residents among the mountains that have met with these birds in that region, except in winter.