полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

The habits and appearance of the birds observed in Europe appear identical with those of our own. Mr. Yarrell states that of all birds these are the most easily tamed, and can be readily made to breed in confinement. In Scotland and in parts of England it is resident throughout the year, in the summer retiring to the bases of the mountains, and there breeding in the underwood that skirts the banks of the mountain streams. It nests in bushes or low trees, such as the alder and the willow. These are constructed of mosses and the stems of dry grasses, intermingled with down from the catkins of the willow, and lined with the same, making them soft and warm. The young are produced late in the season, and are seldom able to fly before the first of July. The parent birds are devoted in their attachment. Pennant relates that in one instance where this bird was sitting on four eggs, she was so tenacious of her nest as to suffer him to take her off with his hand, and after having been released she still refused to leave it. In the winter they descend to the lower grounds, and there feed on the buds of the birch and alder, to reach which they are obliged, like the Titmice, to hang from the ends of the branches, with their backs downward. So intent are they on their work that they are easily taken alive by means of a long stick smeared with birdlime. Mr. Selby states that its notes during the breeding-season, though not delivered in a continuous song, are sweet and pleasing. Captain Scoresby relates that in his approach to Spitsbergen several of these birds alighted on his ship. They were so wearied with their long journey as to be easily caught by the hand. The distance of the nearest point of Norway renders it difficult to imagine how so delicate a bird can perform this journey, or why it should seek such a cold and barren country. European eggs are five in number, of a pale bluish-green, spotted with orange-brown, principally about the larger end. They measure .65 by .50 of an inch.

American eggs of this species average .65 by .53 of an inch. Their color is a light bluish-white, which varies considerably in the depth of its shading, and this tinge is exceedingly fugitive, it being difficult to preserve it even in a cabinet. The eggs are generally and finely dotted with a rusty-brown, and are of a rather rounded oval shape.

Ægiothus canescens, CabanisMEALY RED-POLLLinaria canescens, Gould, “Birds Europe, pl. cxciii.” Linota canescens, Bonap. List, 1838. Acanthis canescens, Bon. Conspectus, 1850, 541.—Bon. & Schlegel, Mon. Loxiens, 1850, 47, tab. li.—Ross, ed. Phil. Jour. 1861, 163. Ægiothus canescens, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 161.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 429.—Coues, P. A. N. S. 1861, 388.—Samuels, 295. “Fringilla borealis, Temminck, 1835. Not of Vieillot.” Bonaparte. ? Fringilla borealis, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 87, pl. cccc. ? Linaria borealis, Aud. Birds Am. III, 1841, 120, pl. clxxviii. “Linaria hornemanni, Holböll, Kroyer Nat. Tidskr. 1843.” Ægiothus exilipes, Coues, Pr. A. N. Sc. Nov. 1861, 385.—Elliot, Illust. N. Am. Birds, I, pl. ix.

Sp. Char. Autumnal female. Greenland race (canescens). (23,377, Greenland, Univ. Zoöl. Mus. Copenhagen.) In general appearance like the corresponding plumage of Æ. linarius, but the whole rump immaculate white; frontal band more than twice as wide as in linarius, and better defined; lower tail-coverts without streaks, their shafts even being white. Carmine vertical patch only a little wider than the whitish frontal patch; head with a strong ochraceous suffusion. Wing, 3.30; tail, 2.90; bill, .35 and .30; tarsus, .60; middle toe, .32. Wing-formula, 1, 2, and 3.

Hab. Greenland. Variations with season probably as in smaller Continental race.

Adult of both sexes in spring. Continental race (exilipes). As described for the Greenland form, but without the ochraceous suffusion. Sides very sparsely streaked.

Male in spring. Breast only tinged with delicate peach-blossom-pink, this extending farther back medially than laterally,—just the reverse of Æ. linarius; a very faint tinge of the same in the white of the rump. Measurements (No. 19,686, Fort Simpson, April 30, 1860; B. R. Ross, Coues’s type): Wing, 3.00; tail, 2.55; bill, .29 and .25; tarsus, .52; middle toe, .30; wing-formula, 2, 1, 3, 4.

Female in spring. Similar, but lacking all red except that of the pileum, which is less intense, though not more restricted, than in the male. Measurements (No. 19,700, Fort Simpson, April 28; B. R. Ross): Wing, 2.80; tail, 2.35; bill, .25 and .22; tarsus, .51; middle toe, .30.

Both sexes in autumn. (♀, Fort Rae.) The white of the whole plumage, except on the rump, overspread by a wash of pale ochraceous, this deepest anteriorly; on the anterior upper parts a deep tint of ochraceous entirely replacing the white; wing-markings broader and more ochraceous than in the spring plumage. Wing, 2.85; tail, 2.50; bill, .30 and .25; tarsus, .51; middle toe, .30.

Hab. Continental arctic America. In winter south into the United States (as far as Mount Carroll, Illinois).

Though Æ. canescens is nearly identical with Æ. linarius in size, these two species may always be distinguished from each other by certain well-marked and constant differences in coloration; the principal of these have been mentioned in the synoptical table, but a few other points may be noted here. In spring males of canescens the delicate rosaceous-pink of the breast does not extend up on to the cheeks, and backward it extends farther medially than laterally, scarcely tingeing the sides at all; while in Æ. linarius the intensely rosaceous, almost carmine, tint covers the cheeks, and extends backward much farther laterally than medially, covering nearly the whole sides.

Though the weakness, or shortness, of the toes compared with the tarsus, is a feature distinguishing, upon almost microscopical comparison, the Æ. canescens in its two races from the races of Æ. linarius, it will not by any means serve to distinguish canescens and exilipes, since, as will be seen by the measurements given, the proportion of the toes to the tarsus is a specific, and not a race, character. (Ridgway.)

Habits. The history of the Mealy Red-Poll can only be presented with some doubts and uncertainties. We cannot always determine how far the accounts given by others may have belonged to this species, and we can only accept, with some reserve, their statements.

This form, whether species or race, is known to inhabit Greenland, where, according to Dr. Reinhardt, it is constantly resident, and I have received its eggs from that country, where its identification was apparently complete. Whether this bird is resident in, regularly migratory to, or only accidental in, Europe, is as yet a question by no means fully settled. Degland gives it as resident in Greenland only, and as accidental in Germany, Belgium, and the north of France. He states that it is known to nest in shrubs and in low trees, and that, in all essential respects, its manners are identical with the common Red-Poll. One of these birds was taken alive in a snare in the vicinity of Abbeville, and kept in a cage, making part of the collection of M. Baillon.

Yarrell thought that sufficient evidence existed of its specific distinctness, but Mr. Gould regarded it as a matter of doubt whether the birds found in Europe were natives, or only arrivals from northern America. He states that among the London dealers this bird, called by them the Stone Red-Poll, is well known, and is considered distinct, but that its occurrence is very rare. Occasionally, at great intervals, they are said to have been abundant.

Mr. Doubleday, of Epping, procured several specimens of this bird in Colchester, in January, 1836, and afterwards obtained a living pair, which he kept for some time. Their notes were much sharper than those of the linarius. Its occurrence was most frequent in winter, many specimens having been obtained in England, and some also in Scotland. Its habits throughout the year are supposed to be very similar to those of the common Red-Poll. Its food is said to be chiefly the seeds of various forest trees.

Mr. Temminck describes what is undoubtedly this species, under the title of borealis. If this supposition be admitted to be correct, its geographical distribution becomes much more clearly defined. He states that it is found during the summer in Norway and Sweden, and is resident of the Arctic Circle throughout the year, and is also found in Northern Asia, as well as in America and in other parts of Europe. He has received specimens from Greenland, and also from Japan, differing in no respect from those found in Europe.

Audubon states that he procured four specimens of this bird in Newfoundland. In their habits he could see no difference between them and the common Red-Poll, but did observe a noticeable difference in their song. He also states that one was shot by Mr. Edward Harris near Moorestown, N. J.

Mr. John Wolley, in his expeditions to Lapland, found there only one species of this genus which was clearly referrible to the Mealy Red-Poll, and was a common resident bird. One of these eggs from Lapland is larger, and a much lighter-colored egg, than any of the common linarius. The ground is a greenish-white, sparingly spotted with dark reddish-brown about the larger end. Its measurement is .80 by .58 of an inch. An egg from Greenland is not perceptibly different in size, color, or markings.

Holböll, in his papers on the fauna of Greenland, demonstrates very distinctly the specific differences between this bird and the linarius. These are its stronger and broader bill, the difference in colors at every age, its much greater size, its very different notes, and its quite different modes of life, the canescens being a strictly resident species, and the linarius being migratory.

In the summer this species is found to the extreme north of Greenland, and has never been known to nest farther south than the 69th parallel. It is more numerous in North Greenland than the linarius, which is rare at the extreme north, while this is very common even at latitude 73°. This bird builds its nests in bushes in the same manner with linarius, and its eggs closely resemble those of that bird. Its notes, he adds, do not at all resemble those of the Red-Poll, but are like those of the Ampelis garrulus.

It is a resident of Greenland throughout the year, and in the winter keeps on the mountains in the interior, but is much more numerous at latitude 66° than farther south. In February, 1826, Holböll saw many flocks on the mountains between Ritenbank and Omanak, and in the journey taken in 1830 by a merchant from Holsteinborg into the interior of the country a great many flocks were observed. They are also frequently met with by reindeer-hunters, who go far into the interior. It is rarely found in South Greenland at any time, and never in the summer. In mild winters they sometimes come about the settlements, as happened in the winter of 1828-29, and again in 1837-38. In the intervening winters it was not seen at Godhaab, and in severe winters it is never to be found near the coast, only single specimens occurring there in spring and autumn.

Mr. MacFarlane thinks this species spends the winter at Fort Anderson, as he has met with it as late as December and as early as February, and believes it to have been present in the vicinity in the interval. It nests in May. Mr. Harriott found one of its nests on the branch of a tree, about five feet from the ground. It contained five eggs.

The egg of this species resembles that of the linarius except in size and its lighter ground-color. The ground is a bluish or greenish white, dotted with a tawny-brown. The egg is of a more oval shape, and measures .75 by .60 of an inch.

Ægiothus flavirostris,112 var. brewsteri, RidgwayBREWSTER’S LINNETSp. Char. General appearance somewhat that of Æ. linarius, but no red on the crown, and the sides and rump tinged with sulphur-yellow; no black gular spot. ♀ ad. Ground-color above light umber, becoming sulphur-yellow on the rump, each feather, even on the crown, with a distinct medial streak of dusky. Beneath white, tinged with fulvous-yellow anteriorly and along the sides; sides and crissum streaked with dusky. Wings and tail dusky; the former with two pale fulvous bands; the secondaries, primaries, and tail-feathers narrowly skirted with whitish sulphur-yellow. A dusky loral spot, and a rather distinct lighter superciliary stripe. Wing, 3.00; tail, 2.50; tarsus, .50; middle toe, .30. Wing-formula, 1, 2, 3, etc.

Hab. Massachusetts.

As the present article on Ægiothus is going to press, we have received, through the kindness of Dr. Brewer, a specimen of what appears to be a third species of Ægiothus, allied to the Æ. flavirostris of Europe, obtained in Waltham, Mass., by Mr. William Brewster, of Cambridge. This bird was killed in a flock of Æ. linarius, of which five were also shot at the same discharge. None of the others, nor indeed of any of ninety specimens prepared by Mr. Brewster during the winter, were at all like the present one, which is entirely different from anything we have ever seen from North America.

The relationship of this bird appears to be nearest to the Æ. flavirostris of Europe, with the ♀ of which it agrees in many respects, as distinguished from linarius and canescens. The European bird, however, lacks the sulphur-yellow tinge (which gives it somewhat the appearance of Chrysomitris pinus), has the throat and jugulum strongly reddish-buff, instead of dingy yellowish-white, and is much browner above; besides which the tail is longer and less deeply forked, with narrower feathers.

Habits. Nothing distinctive was observed by Mr. Brewster in regard to the habits of the specimen killed by him.

Genus LEUCOSTICTE, SwainsonLeucosticte, Swainson, Fauna Bor. Am. II, 1831, 265. (Type, Linaria tephrocotis, Sw.)

Leucosticte tephrocotis.

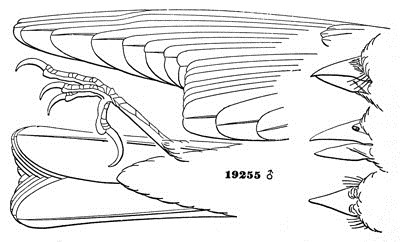

19255 ♂

Gen. Char. Bill conical, rounded, rather blunt at the tip; the culmen slightly convex; the commissure slightly concave; the nostrils and base of commissure concealed by depressed bristly feathers; a depressed ridge extending about parallel with the culmen above the middle of the bill. Another more conspicuously angulated one extending forward from the lower posterior angle of the side of the lower mandible, nearly parallel with the gonys. Tarsus about equal to the middle toe and claw. Inner toe almost the longer, its claw not reaching beyond the base of the middle one. Hind toe rather longer, its claw longer than the digital portion. Wings very long; first quill longest; all the primaries longer than the secondaries. Tail forked.

This genus differs from Ægiothus in the more obtuse and curved bill, the less development of bristly feathers at the base, the ridge on the lower mandible, the lateral toe not reaching beyond the base of the middle one, and possibly a longer hind toe. Its relationship to the other allies will be found expressed in the synoptical table of Coccothraustinæ.

Leucosticte tephrocotis.

The number of American species, or at least races, of this genus has been increased considerably since the publication of Birds of North America, five now belonging to the American fauna, instead of the three there mentioned. Of the species usually assigned to the genus, one, L. arctoa, is quite different in form, lacking the ridge of the mandible, etc., and in having the ends of the secondaries graduated in the closed wing, instead of being all on the same line. The colors, too, are normally different; in arctoa being dusky, with silvery-gray wings and tail, without rose tips to the feathers of the posterior part of body; and in Leucosticte proper, the wings and tail being dark-brown narrowly edged with whitish, or more broadly, like the ends of the feathers of the body behind, with rose-color. For the present, however, we shall combine the species, not having before us any American specimens of L. arctoa.

From the regular gradation of each form into the other—the extremes being thus connected by an unbroken chain of intermediate forms—it seems reasonable to consider all the North American forms as referable to one species (L. tephrocotis, Sw., 1831) as geographical races. They may be distinguished as follows:—

Common Characters. Body anteriorly chocolate-brown; posteriorly tinged with rose-red. Wing-coverts (broadly) and quills edged with the same. Head above light ashy or silvery-gray, as are also the feathers around the base of upper mandible; the forehead and a patch on crown blackish. Throat dusky.

Additional Characters. The chocolate-colored feathers and the secondary quills, sometimes the tail-feathers and greater wing-coverts, edged with pale brownish-white or fulvous; the interscapulars with darker centres. Rose of rump and upper tail-coverts in form of transverse bands at end of feathers, that of abdomen more a continuous wash. Lining of wings and axillars white, tinged with rose at ends of feathers. Feathers of crissum dark brown, edged with whitish, sometimes tinged with rose. Bill generally reddish or yellowish, with blackish tip.

A. Auriculars chocolate-brown.

1. Whole side of head below the eye, including the auriculars, chocolate-brown. Chin not bordered anteriorly with ash. In the breeding-season, head darker and ash wanting. Wing, 4.35; tail, 3.00; bill, .44; tarsus, .72. Hab. Interior regions of North America. … var. tephrocotis.

2. Cheeks, lores, and anterior border of the chin ash-color. Wing, 4.00; tail, 2.80; bill, .44; tarsus, .70. Hab. Colorado and Wyoming Territories … var. campestris.

B. Auriculars ash-color.

3. Wing, 4.30; tail, 3.00; bill, .40; tarsus (?). Chocolate of the breast, etc., light, exactly as in tephrocotis; rose beneath restricted to the abdomen; lores and chin light ash. Hab. Northwest coast from Kodiak to Fort Simpson, east to Wyoming Territory … var. littoralis.

4. Wing, 4.60; tail, 3.40; bill, .40; tarsus, .78. Chocolate very dark, inclining to sepia; rose extending forward on to the breast; lores blackish; chin dusky gray. Hab. Aleutian Islands (St. George’s, Unalaschka, and Kodiak) … var. griseinucha.

A closely allied species113 from Kamtschatka and the Kurile Island differs mainly in having the nasal feathers as well as the head blackish, but without distinct patch on the top, and the nape rusty, in contrast with the back. It is about the size of L. tephrocotis. This species may yet be detected in the westernmost Aleutians.

Leucosticte tephrocotis,114 SwainsonGRAY-CROWNED FINCHLinaria (Leucosticte) tephrocotis, Sw. F. Bor. Am. II, 1831, 255, pl. 1. Leucosticte tephrocotis, Sw. Birds II, 1837.—Bon. Consp. 1850, 536.—Baird, Stansbury’s Salt Lake, 1852, 317.—Ib. Birds N. Am. 1858, 430.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 164. Erythrospiza tephrocotis, Bon. List, 1838.—Aud. Syn. 1839.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 176, pl. cxcviii. Fringilla tephrocotis, Aud. Orn. Biog. V. 1839, 232, pl. ccccxxiv.

Sp. Char. (No. 19,255.) Male in winter. General color dark chocolate-brown or umber, lighter and more chestnut below; the feathers to a considerable degree with paler edges (most evident in immature specimens), those of back with darker centres. Nasal bristly feathers, and those along base of maxilla, and the hind head to nape ash-gray, this color forming a square patch on top of head, and not extending below level of eyes. A frontal blackish patch extending from base of bill (excepting the bristly feathers immediately adjacent to it), and reaching somewhat beyond the line of the eyes, with convex outline behind, and extending less distinctly on the loral region. Chin and throat darker chestnut, not grayish anteriorly. Body behind dusky; the feathers of abdomen and flanks washed, and of crissum, rump, and upper tail-coverts tipped, with rose-red; wing-coverts, and to some extent quills, edged with the same; otherwise with white. Bill yellowish, with dusky tip; feet black. Length before skinning, 6.50; extent, 11.50. Skin: Length, 6.50; wing, 4.30; tail, 3.00.

Young. Pattern of coloration as in the adult of L. tephrocotis; ash similarly restricted, but with the black frontal patch badly defined. The brown of the plumage, however, is of an entirely different shade from that of adult specimens of tephrocotis, being of a blackish-sepia cast, much darker, even, than in griseinucha; each feather also broadly bordered terminally with paler, these borders being whitish on the throat and breast, brownish on the nape and back, and light rose (broadly) on the scapulars. The whole abdomen, flanks, and crissum are nearly continuously peach-blossom pink, which, with that of the lesser and middle wing-coverts and rump, is of a finer and brighter tint than in adults. The other edgings to wings are pale ochraceous; under side of wing pure white. Bill dull yellow, dusky toward tip. Wing, 4.20; tail, 3.80. (60,638, Uintah Mountains, Utah, September 20, 1870; Dr. F. V. Hayden.)

The young specimen described was obtained during the summer of 1871 in the Uintah Mountains; and were it not unmistakably a bird of the year, it would be considered almost a distinct species, so different is it from adult specimens of tephrocotis.

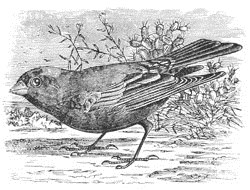

Habits. Of the history and habits of this well-marked and strikingly peculiar bird, but little is known. It was first described by Swainson from a single specimen, obtained on the Saskatchewan Plains, in May, by Dr. Richardson’s party. Specimens were afterwards procured in Captain Stansbury’s expedition, near Salt Lake City, Utah, in March, 1850. Dr. Hayden found them very abundant on the Laramie Plains during the winter season, and Mr. Pearsall obtained numbers about Fort Benton. Dr. Cooper has also seen one specimen brought from somewhere east of Lake Tahoe, in Washoe, by Mr. F. Gruber. They were said to be plentiful there in the cold winter of 1861-62. Dr. Cooper thinks it probable that they visit the similar country east of the northern Sierra Nevada, in California.

A single flock of what is presumed to have been this species was seen by Mr. Ridgway, on the 5th of January, in the outskirts of Virginia City, Nevada. The flock was flitting restlessly over the snow in the manner of the Plectrophanes.

Nothing has been ascertained, so far as we are now informed, as to its nest, eggs, or general distribution during the breeding-season.

Mr. J. K. Lord states that he met with a flock of these rare and beautiful birds on the summit of the Cascade Mountains. It was late in October, and he observed a flock of nine or ten birds pecking along the ground, and feeding somewhat in the manner of Larks. Puzzled to know what birds they could be at such an altitude so late in the year, he fired among them and secured three, a female and two males in fine plumage. (Perhaps var. littoralis.)

In July of the following summer, on the summit of the Rocky Mountains, near the Kootanie Pass, he again saw these birds feeding on the ground. He shot several, but they were all young birds of the year. It is therefore rendered probable that these Finches breed on the Cascade and Rocky Mountains, in both at about the same altitude, or seven thousand feet, coming into the lowlands during the winter, as it is not likely that they could endure the cold of the summits, or find there a sufficiency of food, the winter being very severe, and the snow three feet, or more in depth.

Mr. Charles N. Holden, a promising young ornithologist of Chicago, who observed these birds among the Black Hills, near Sherman, at an altitude of eight thousand feet above the sea, has furnished me with interesting observations in regard to them. He informs me that he did not meet with these birds there in summer. They came in small flocks in the coldest part of winter. Their food consisted of small seeds and insects. In some instances he found the crops so distended with seeds as to distort their shape. They become very fat, and are excellent eating. In one specimen, a young male, the plumage was almost black, as described at the beginning of this article. These birds were quite numerous, and nearly forty specimens were secured. He was not able to learn anything in reference to their breeding-places. Except by dissection, he found it difficult to distinguish between a young male of the first year and a female.