полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

PLATE XXIV.

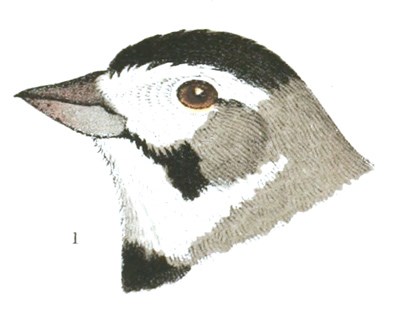

1. Plectrophanes maccowni. ♂ Dakota, 35951.

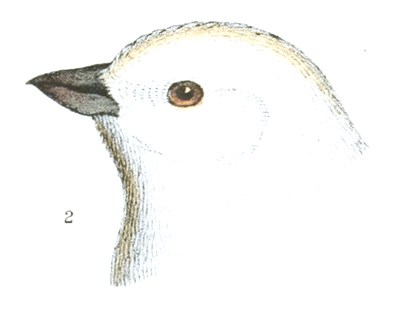

2. Plectrophanes nivalis. ♂ Ft. Resolution, B. A., 19632.

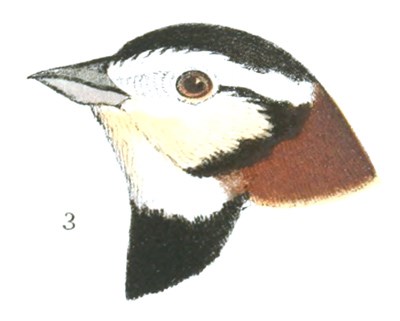

3. Plectrophanes ornatus. ♂ Ft. Union, Dakota, 1907.

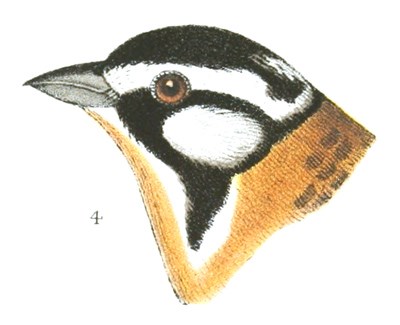

4. Plectrophanes pictus. ♂ Ft. Simpson, B. A., 19659.

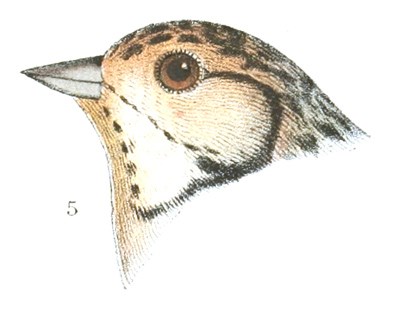

5. Plectrophanes pictus. ♀ 19664.

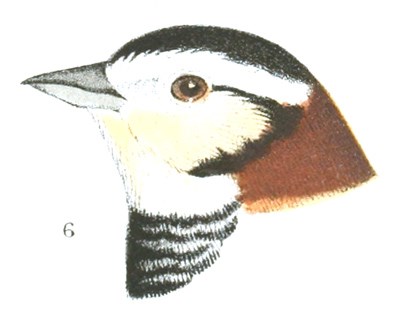

6. Plectrophanes melanomus. ♂ Dakota, 35359.

7. Plectrophanes lapponicus. ♂ Ft. Resolution, B. A., 19647.

8. Passerculus savanna D. C., 10145.

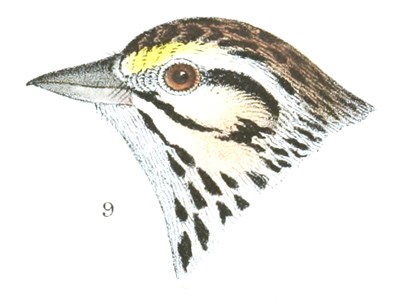

9. Passerculus sandwichensis. Washington Ter., 6343.

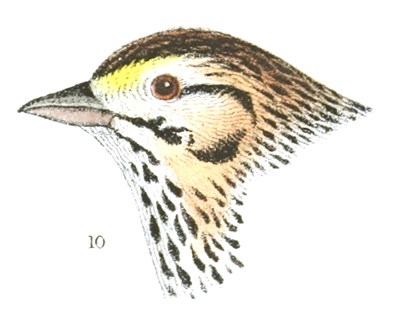

10. Passerculus anthinus. Cal. (Petaluma), 5555.

Passerculus alaudinus. Utah, 53483.

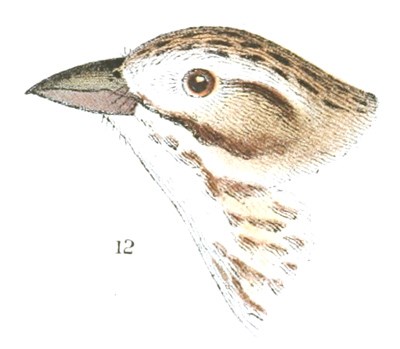

12. Passerculus rostratus. Cal. (San Diego), 6340.

Dr. Coues mentions the taking of a single specimen of this species, October 17, on the open grassy plains of Arizona.

This species is also given by Mr. Sumichrast as a resident throughout the year of the great plains of the plateau of Mexico. From them it occasionally descends to the distant intervals, as far as Orizaba, or at the elevation, above the gulf-level, of 1,220 metres.

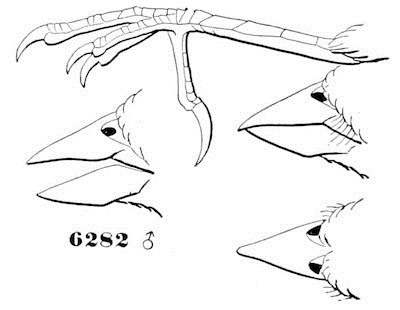

Plectrophanes maccowni, LawrenceCHESTNUT-SHOULDERED LONGSPUR; MACCOWN’S BUNTINGPlectrophanes maccowni, Lawrence, Ann. N. Y. Lyc. V, Sept. 1851, 122. Western Texas.—Cassin, Illust. I, viii, 1855, 228, pl. xxxix.—Heerm. X, c, p. 13.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 437.

Plectrophanes maccownii, Lawr.

6282 ♂

Sp. Char. Male in spring. Top of head, a broad stripe each side the throat from lower mandible, and a broad crescent on jugulum, black; side of head including lores and band above the eye, throat, and under parts, ashy-white; ear-coverts bordered above and behind by blackish, running out at the maxillary stripe. Breast just behind the black crescent and sides, showing dark bases of feathers. Upper parts ashy, tinged with yellowish on the mandible, and streaked with dusky; least so on nape and rump. Lesser wing-coverts ashy; median chestnut-brown, with blackish bases sometimes evident; the quills all bordered broadly externally with whitish, becoming more ashy on secondaries. Tail-feathers white except at the concealed bases and the ends, which have a transverse (not oblique) tip of blackish; the outermost white to the end; the two central like the back. Bill dark plumbeous; legs blackish. In winter the markings more or less obscured; the bill and legs more yellowish.

Female lacks the black markings, which, however, are indicated obsoletely as in other Plectrophanes; there is no trace of chestnut on the wings, no streaks on the breast. Length, 5.50; wing, 3.60; tail, 2.50; bill, .46.

Hab. Eastern slopes of Rocky Mountains, from Texas to Upper Missouri.

This species varies considerably in markings, but is readily recognized among other Plectrophanes in all stages by short hind toe, very stout bill, and the transverse dark bar at the end of all tail-feathers except the inner and outer.

Habits. Maccown’s Lark Bunting is yet another of the various species of our birds whose history is very little known, and in regard to which the most we are able to state, at present, is that they appear in different parts of the interior plains of the United States, between the Rocky Mountains and the Missouri River and the lower tributaries of the Mississippi, extending from New Mexico and Texas northward, during the breeding-season, to the northern boundary of the United States. It was first discovered by Captain Maccown, who obtained it in Texas, where he found it in company with a flock of Shore Larks, and where it winters in considerable numbers. Mr. Dresser afterward met with it in small flocks, early in April, on the prairies near San Antonio. It was not very common, and he was only able to obtain two specimens during his stay in that section.

Dr. Heermann found this species congregated in large flocks, in company with the Black-shouldered Bunting. They were engaged in gleaning the seeds from the scanty grass, on the vast arid plains of New Mexico. Insects and berries formed also a part of their food; in search of these they showed great activity, running about with celerity and ease. In the spring, large flocks were seen at Fort Thorn, having migrated thither from the North the previous fall. With the return of mild weather they again departed for the North for the purposes of incubation. Among these large flocks Dr. Heermann noticed also the Shore Lark, but they formed only a small proportion of the whole number.

In a letter to Mr. Cassin, Dr. Heermann states that he found this species congregated with large numbers of other birds about the isolated water-holes in the barren plains of New Mexico.

Mr. J. A. Allen states (Am. Nat., May, 1872) that, during a few weeks’ stay near Fort Hays in midwinter, he found Maccown’s Longspur tolerably frequent in that vicinity.

An egg of this species, in the collection of the late Dr. Henry Bryant, measures .80 by .60 of an inch. Its ground-color is a light bluish clay-color, marbled, dotted, blotched, and lined with light neutral tints of lavender and darker markings of purplish and reddish brown. The nest was placed on the ground, and is composed entirely of coarse grass-stems (No. 3,521, J. Pearsall, Fort Benton).

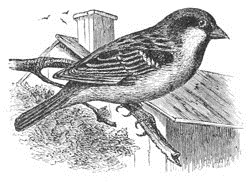

Subfamily PYRGITINÆ

The introduction into the United States, at so many distant points, of the European House Sparrow (Pyrgita domestica) renders it necessary to introduce it with any work treating of the birds of North America, although totally different in so many features from our own native forms. I follow Degland and Gerbe in placing the genus Pyrgita in a separate subfamily (Pyrgitinæ, see page 446), without any distinct idea of its true affinities, as it does not come legitimately within any of the subfamilies established for the American genera. In some respects similar to certain Coccothraustinæ, in the short tarsi and covered nostrils, the wings are shorter and more rounded, the sides of the bill with stiff bristles, etc. The much larger, more vaulted bill, weaker feet, and covered nostrils, distinguish it from Spizellinæ.

Genus PYRGITA, CuvierPyrgita, Cuvier, R. A. 1817. (Type, Fringilla domestica, Linn.)

Passer, Brisson, Orn. 1760. Same type. Degland & Gerbe, Orn. Europ. I, 1867, 239.

Gen. Char. Bill robust, swollen, without any distinct ridge; upper and under outlines curved; margins inflexed; palate vaulted, without any knob; nostrils covered by sparse, short, incumbent feathers; side of bill with stiff, appressed bristles. Tarsi short and stout, about equal to or shorter than the middle toes; claws short, stout, and considerably curved. Wings longer than tail; somewhat pointed. Tail nearly even, emarginated, and slightly rounded.

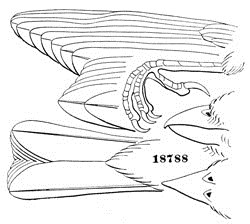

Pyrgita domestica, CuvTHE HOUSE SPARROWFringilla domestica, Linn. Syst. Nat. 12th ed. 323, 1766. Pyrgita domestica, Cuv. Reg. An. 2d ed. (1829), I, 439. Passer domesticus, Degland & Gerbe, Ornith. Europ. I, 1867, 241.

Pyrgita domestica.

18788

Sp. Char. Male. Above chestnut-brown; the interscapular feathers streaked by black on inner webs; the top of head and nape, lower back, rump, and tail-coverts plain ashy; narrow frontal line, lores, chin, throat, and jugulum black; rest of under parts grayish, nearly white along median region. A broad chestnut-brown stripe from behind eye, running into the chestnut of back; cheeks and sides of neck white; outside of closed wing, pale chestnut-brown, with a broad white band on the middle coverts, and behind showing the brown quills; the lesser coverts dark chestnut like the head stripe. Tail dark brown, edged with pale chestnut. Bill black; feet reddish. Iris brown.

Female. Duller of color, and lacking the black of face and throat; breast and abdomen reddish-ash; cheeks ashy; a yellow-ochre band above and behind the eyes, and across the wings. Head and neck above brownish-ash; body above reddish-ash, streaked longitudinally with black.

Male in winter. The colors generally less distinct. Length, 6.00; wing, 2.85; tail, 2.50; tarsus, .70; middle toe and claw, .60.

The House Sparrow of Europe has been introduced into so many parts of the United States as to render it probable that at no distant day it will have become one of our most familiar species. Brought over to the New World within a comparatively few years, it has commenced to multiply about the larger cities, especially in the environs of New York, as also about Portland, Boston, Newark, and Philadelphia. The first effort made to naturalize it about Washington failed in consequence of the death of three hundred individuals imported by the Smithsonian Institution. A second, however, in 1871, was more successful. One thousand birds were let loose in the public squares of Philadelphia in the spring of 1869. In and about Havana it is said to be common, as also about Great Salt Lake, where it was recently introduced by the Mormons, according to Mr. J. A. Allen.

Pyrgita domestica.

Habits. The common House Sparrow of Europe has, within the past few years, achieved a right to a place in the avi-fauna of North America by its complete introduction, and its reproduction in large numbers, in various parts of the country, from Portland, Me., to Washington City, as also about Salt Lake.

The first attempt to introduce these birds, within my knowledge, was made by a gentleman named Deblois, in Portland, Me., in the fall of 1858. Six birds were set at liberty in a large garden in the central part of the city. They remained in the neighborhood through the winter, and in the sheltering porch of a neighboring church they found places of shelter and security. In the following spring three nests were built in dwarf pear-trees in the garden in which they were first set at liberty. One, at least, of these nests, was successfully occupied, and six young birds were reared from it. A second nest, with four young, was also hatched by the same pair. Neither of these nests was globular in shape, but open and coarse, built of hay and straws. These nests were taken, after their use, and came into my possession. Since then I have been informed that these birds increased and multiplied, and for a while were quite abundant in that portion of the city, and a large colony of this Sparrow appeared in the winter of 1871 in Rockland, Me.

Two years later, Mr. Eugene Schieffelin, of New York, imported and set at liberty, near Madison Square, in that city, twelve of these birds, and this he repeated for several successive summers. In 1864, fourteen birds were set at liberty in Central Park, by the Commissioners. Other birds were also brought from England, by different parties, in the Cunard steamers, and released at Jersey City. These have increased very largely, and have spread to the adjoining cities, until these birds have become familiar and social residents in all the large cities and towns within an extended area around New York, as well as in all parts of that city.

They were introduced into Boston by the City Government in 1868. Two hundred birds were purchased in Germany, but unfortunately all died on their passage except about a score. These were set at liberty in June, but, weakened by their sea-voyage, several of them were found dead in the deer-park, and the rest disappeared. The following summer more were imported, but all died except ten. These were well cared for, and only released when in excellent condition. For some months nothing was seen of these birds, and the experiment was supposed to be a failure, when it was ascertained that they had betaken themselves to the vicinity of stables in the southern part of the city, had increased and multiplied in large numbers, reappearing in the winter to the number of one hundred and fifty. They were regularly fed by the city forester each day in the deer-park, and roosted at night in the thatch of the roofs of the buildings. Since then they have very largely increased. About twenty, that same summer, were set at liberty in Monument Square, Charlestown.

In 1869 about one thousand birds were imported, by the City Government, into Philadelphia. Fortunately they came in good condition, and being released early in May immediately separated into scattered parties and prepared for themselves new homes. Some appeared in Morristown and other distant towns in New Jersey. Others wandered to Germantown, and the remoter suburbs of Philadelphia, where they found the cherry-trees in full blossom, and where their exploits in stripping the blooms from the trees gave a not very favorable first impression of these new-comers.

It has been exceedingly interesting to watch the manners and habits of these strangers in their new homes. They have become quite tame, are fearless and gentle, and as they have been very kindly treated live in a condition of semi-domestication. At first they built their nests, and passed their winters, in New York, among the thick ivies that cover the walls of so many churches, in such cases building globular nests. As soon, however, as suitable boxes were prepared for them in sufficient quantities, these were taken possession of in preference to anything else.

At the time of their introduction the shade-trees in the parks and squares of New York, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Newark, and other places, were greatly infested with the larvæ of the measure-worms that destroyed their foliage. Since then these worms have almost entirely disappeared. A doubt has been expressed whether the Sparrows destroy these insects. That they eat them in the larvæ form I do not know, but to their destruction of the chrysalis, the moth, and the eggs, I can testify, having been eye-witness to the act.

Apprehensions have been expressed lest these new-comers may molest and drive away our own native birds. How this may be when the Sparrows become more numerous cannot now be determined, but so far they manifest no such disposition. Since their introduction into Boston the Chipping Sparrows appear to have increased, and to associate by preference with their European visitors, feeding with them unmolested. I have been unable to detect a single instance in which they have been molested, in any manner, by their larger companions. Their predatory aggressions, however, upon the rights of the common Robin have been noticed, and deserve mention. The Sparrows appear to be extravagantly fond of earthworms, but not able to hunt for them themselves. They have learned to watch the Robin as it forages for these worms, keeping around, at a respectful distance, and as soon as one, with much toil, has dragged a worm from its place of concealment, down swoops the bird and impudently carries it off. The poor bewildered and plundered Robin essays a late and vain attempt to protect its food. The Sparrow is too nimble, and the worm is gone before its rightful owner can turn to face the robber.

The Sparrows endure the severest of the winter weather without any apparent inconvenience, appearing as cheerful, contented, and noisy with the thermometer at zero as at any other time. They are quite fearless, especially in New York, running about under the feet of the passers-by with perfect indifference and confidence. In Boston I have noticed their nests in convenient places, a few feet above crowded sidewalks. In winter they come regularly about the houses to be fed.

The House Sparrow has also been introduced into Australia, where it has become acclimated, and was, at the last accounts, rapidly increasing in that quarter. It is likewise very common about Havana, Cuba.

In the Old World this bird has a widely extended area of distribution, and is resident wherever found. It is very abundant in the British Islands and throughout the northern and central portions of Europe. In Spain and in Italy it is replaced by two closely allied species or races. This bird, however, is also found in North Africa, in the Levant, at Trebizonde, and among the mountains of Nubia. Specimens have also been received from the Himalayas, from Nepaul, and the vicinity of Calcutta.

Both in Europe and in this country the Sparrows pair early in the season. I have known them sitting on their eggs, in Boston, in March. They are very prolific, have broods of five, six, and even seven at a time, three or four times in a season. They are full of life and animation, somewhat disposed to brief and noisy quarrels, which are always harmless.

Their great attachment and devotion to their young is dwelt upon by all English writers as quite remarkable. They evince a great partiality for warmth, and even in midsummer line their nests with all the feathers they can pick up. In New York it is a favorite amusement with the children to carry with them to the public parks quantities of feathers, which they throw, one by one, to the Sparrows, to witness their amusing contests for possession.

The eggs of this bird are oval in shape, pointed at one end, with a ground of a light ashen color, blotched, dotted, and streaked with various shades of ashy and dusky brown. They measure from .85 to .95 of an inch in length, and from .60 to .65 in breadth.

Subfamily SPIZELLINÆ.—The Sparrows

Char. Bill variable, usually almost straight; sometimes curved. Commissure generally nearly straight, or slightly concave. Upper mandible wider than lower. Nostrils exposed. Wings moderate; the outer primaries not much rounded. Tail variable. Feet large; tarsi mostly longer than the middle toe.

The species are usually small, and of dull color, though frequently handsomely marked. Nearly all are streaked on the back and crown, often on the belly. None of the United States species have any red, blue, or orange, and the yellow, when present, is as a superciliary streak, or on the elbow edge of the wing.

In the arrangement of this subfamily, as of the others belonging to the Fringillidæ, we do not profess to give anything like a natural system, but merely an attempt at a convenient artificial scheme by which the determination of the genera may be facilitated.

A. Tail small and short; considerably or decidedly shorter than the wings, owing either to the elongation of the wing or the shortening of the tail. Lateral toes shorter than the middle without its claw. Species streaked above and below. (Passerculeæ.)

a. Thickly streaked everywhere above, on the sides, and across the breast. Wing pointed; longest primaries considerably longer than the secondaries. Tail forked.

Centronyx. Hind claw very large; rather longer than its digit. The hind toe and claw, together, as long as or longer than the middle toe and claw. Other toes as in Passerculus. Claws gently curved. Tertials shorter than the secondaries. Tail forked, but the lateral feathers shorter.

Passerculus. Hind claw as long as its digit; the toe equal to the middle one without its claw; lateral toes falling considerably short of the middle claw. Wings very long; first primary longest. Tertials as long as the primaries. Tail forked; feathers acute.

Poocætes. Hind claw shorter than its digit; the whole toe less than the middle toe without its claw. Lateral toes nearly equal to the middle one, without its claw. Tertials but little longer than secondaries. Tail stiffened, forked; feathers acute, outer ones white.

b. Moderately streaked above, on the sides, and on the breast, the latter sometimes unstreaked; the dorsal streaks broader, the others fainter than in the last. Wings short, reaching a little beyond the base of the tail. Not much difference between the primaries and secondaries. Tail short, graduated, and the feathers lanceolate, acute.

Coturniculus. Bill short; thick. Tertials almost equal to the primaries; truncate at the end. Claws small, weak; hinder one shorter than its digit. Outstretched feet not reaching the tip of the tail. Tail-feathers not stiffened. (In one species tail nearly equal to the wing.)

Ammodromus. Bill slender, small at base, and elongated. Tertials not longer than the secondaries; rounded at the tip. Claws large, hinder one equal to its digit. Outstretched toes reaching considerably beyond the end of the stiffened, almost scansorial tail.

B. Tail longer and broader; nearly or quite as long as, sometimes a very little longer than, the wings, which are rather lengthened. The primaries considerably longer than the secondaries. None of the species streaked beneath, and the back alone streaked above. (Spizelleæ.)

a. Tail rounded or slightly graduated.

Chondestes. Tail considerably graduated, not emarginated. Lateral toes considerably shorter than the middle toe, without its claw. Wings very long, decidedly longer than the tail, reaching the middle of the tail. First quill longest. Head striped. Back streaked. White beneath. A white blotch on the end of the tail-feathers.

Zonotrichia. Tail moderately graduated. Wings moderate, about as long as the tail, reaching about over the basal fourth of the tail; first quill less than the second to fourth. Feet large. Head striped with black and white, or with brown and ochraceous. Back streaked.

Junco. Tail very nearly equal to the wings, slightly emarginate, and decidedly rounded. Outer toe rather longer than inner, reaching the middle claw. No streaks anywhere except in young; black or ash-color above; belly white; with or without a rufous back and sides. Outer tail-feathers white.

Poospiza. Tail lengthened, slightly graduated; the feathers unusually broad to the end. Bill slender. Wings about as long as the tail, reaching but little beyond its external base. Tertials broad, and, with the secondaries, rather lengthened. Second to fifth quills nearly equal, and longest. Bill dark lead-color. Tail black. Uniform ashy-brown above; white beneath. Sides of head with stripes of black and white.

b. Tail decidedly forked; a little shorter than the wing, sometimes a little longer.

Spizella. Size rather small. Wings long. Lower mandible largest. Uniform beneath, or with a pectoral spot or the chin black.