полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

Early in May, 1859, a pair of these birds built their nest in the garden of Professor Benjamin Peirce, in Cambridge, Mass., near the colleges. It was found on the 9th by Mr. Frederick Ware, and already contained its full complement of four eggs, partly incubated. This nest was three inches in height and four in diameter. The depth of the cavity, as well as its diameter at the rim, was two inches. The base of this nest was a mass of loose materials, and the lower portions of the sides were hardly different. The upper and the inner portions of this fabric were much more compactly and neatly woven, or rather felted together. The outer layers consisted of small twigs of the Thuja, dried stems and ends of pine twigs, grasses, sedges, stalks of small vegetables, fine roots, bits of wool, and coarse hair. The whole was very closely lined with fine dry roots of herbaceous plants and the hair of small quadrupeds.

The eggs are of an oblong-oval shape, of a light green ground-color, spotted, chiefly at the larger end, with markings of a light rusty-brown. They measure .71 by .50 of an inch. They have a marked resemblance to the eggs of the Linariæ, but the ground-color is of a slightly lighter shade.

A nest of this species, found May 15, 1868, at Brunich, Canada, was composed almost entirely of pine twigs interlaced in a very neat and artistic manner. Its diameter was three and a half inches, and its height two inches. It was lined with hair. The cavity was one and a half inches deep and two inches wide.

Genus LOXIA, LinnæusLoxia, Linnæus, Syst. Nat. ed. 10, 758. (Type, Loxia curvirostra, L.)

Curvirostra, “Scopoli, 1777.” (Type, L. curvirostra.)

Loxia americana.

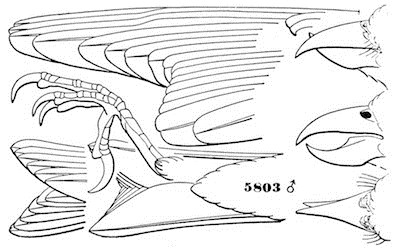

5803 ♂

Gen. Char. Mandibles much elongated, compressed and attenuated; greatly curved or falcate, the points crossing or overlapping to a greater or less degree. Tarsi very short; claws all very long, the lateral extending beyond the middle of the central; hind claw longer than its digit. Wings very long and pointed, reaching beyond the middle of the narrow, forked tail.

Colors reddish in the male.

The elongated, compressed, falcate-curved, and overlapping mandibles readily characterize this genus among birds. This feature, however, only belongs to grown specimens, the young having a straight bill, as in other Finches.

The United States species of Loxia are readily distinguished by the presence of white bands on the wing in leucoptera and their absence in americana. Neither form, however, is to be considered as specifically distinct from their European allies. The differences are as follows:—

Species and VarietiesL. curvirostra. Wings dusky, without white bands.

1. Bill from forehead, .74; wing, 3.90; tail, 2.40. Lower mandible much weaker than the upper. Hab. Europe … var. curvirostra.110

2. Bill from forehead, .80 or more; wing, 4.00; tail, 2.50. Lower mandible as strong as the upper. Hab. Rocky Mountains of United States, and mountainous regions of Mexico … var. mexicana.

3. Bill from forehead, .60 or less; wing, 3.30; tail, 2.20. Hab. North America generally … var. americana.

L. leucoptera. Wings deep black, with two broad white bands.

1. Body and head pomegranate-red; black of scapulars nearly meeting across lower back. Hab. Northern North America; “Himalayas”; “Japan” … var. leucoptera.

2. Body, etc., cinnabar-red; back nearly wholly red. Hab. Europe … var. bifasciata.111

Loxia curvirostra var. americana, BairdRED CROSSBILLCurvirostra americana, Wils. Am. Orn. IV, 1811, 44, pl. xxxi, f. 1, 2.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 426.—Cooper & Suckley, 198.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. Ac. I, 1869, 281 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 148.—Samuels, 291. Loxia americana, Bon. List, 1838.—Bon. & Schlegel, Mon. Loxiens, 5, tab. vi.—Newberry, Zoöl. California and Oregon Route, P. R. R. Rep. VI, IV, 1857, 87.—Bon. & Schlegel, Mon. Lox. 5, pl. vi. Loxia curvirostra, Forster, Phil. Trans. LXII, 1772, No. 23. Aud. Biog. II, 1834, 559; V, 511, pl. cxcvii.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 186, pl. cc. "Loxia pusilla, Illiger” (Bp.). “Loxia fusca, Vieillot” (Bp.).

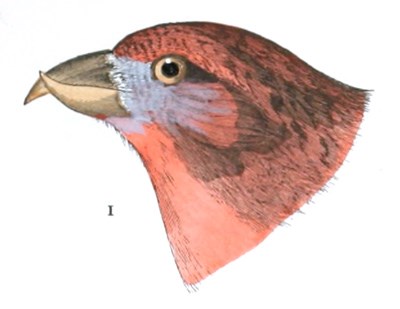

Sp. Char. Old male dull red (the shade differing in the specimen, sometimes brick-red, sometimes vermilion, etc.); darkest across the back; wings and tail dark blackish-brown. Young male yellowish. Female dull greenish-olive above, each feather with a dusky centre; rump and crown bright greenish-yellow. Beneath grayish; tinged, especially on the sides of the body, with greenish-yellow. Young olive above; whitish beneath, conspicuously streaked above and below with blackish. Male about 6 inches; wing, 3.30; tail, 2.25.

Loxia americana.

Hab. Northern America generally, coming southward in winter. Resident in the Alleghany and Rocky Mountains.

There are considerable differences both in color and size, especially of bill, in specimens from various parts of North America, and to a less degree from the same locality. While those of the Atlantic and Pacific coast have bills of much the same size, in skins from the mountains of California this member is much stouter; in this character approaching the L. mexicana of Strickland, in which the bill presents its maximum of the North American form.

18034 ♂ California.

It would not probably be far out of the way to consider the European and all the American common Crossbills as the same species, differing only as races, and perhaps including L. himalayana, which is smaller even than americana.

We have not observed any American Crossbills with two reddish bands across the wing-coverts, corresponding to the variety rubrifasciata of Europe.

L. pytiopsittacus of Europe is much the largest of all the species, measuring seven inches in length, and with the bill seven lines high at base.

PLATE XXIII.

1. Loxia americana. ♂ W. Ter., 6442.

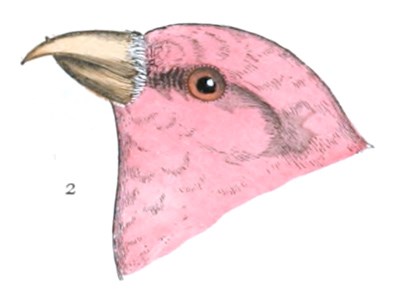

2. Loxia leucoptera. ♂ Philad., 1215.

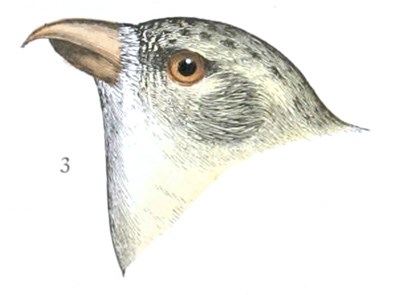

3. Loxia leucoptera. ♀ Alaska (Yukon), 27360.

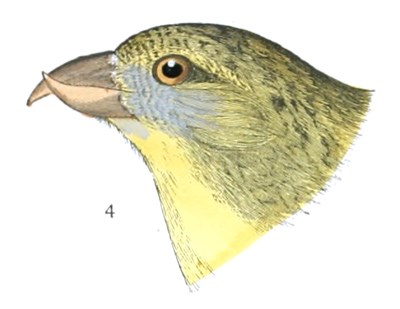

4. Loxia americana. ♀.

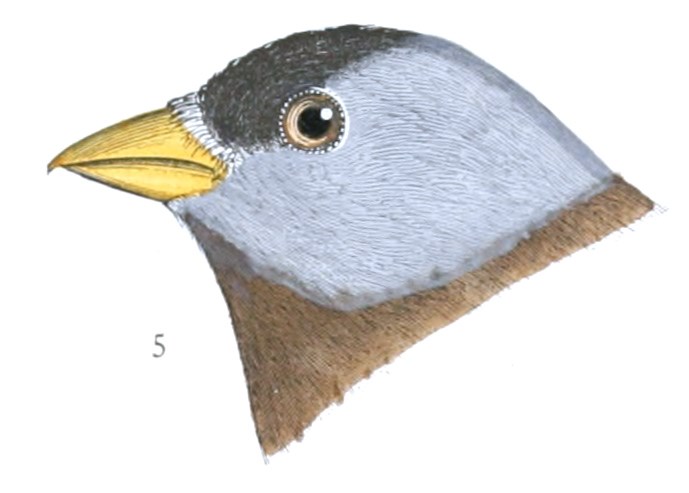

5. Leucosticte griseinucha. ♂ Unalaska, 54244.

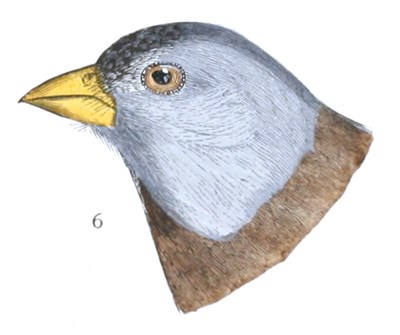

6. Leucosticte littoralis. Ft. Simpson, V. I.

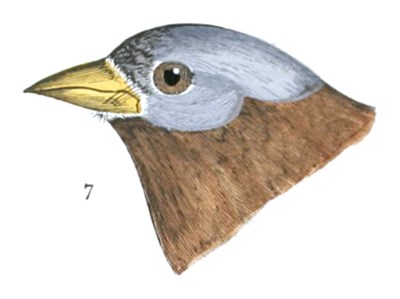

7. Leucosticte campestris. Colorado, 41527.

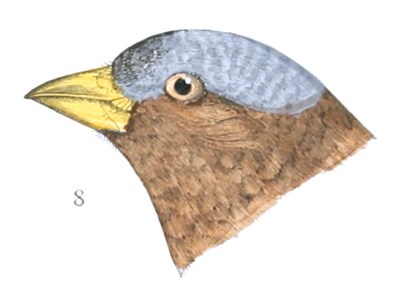

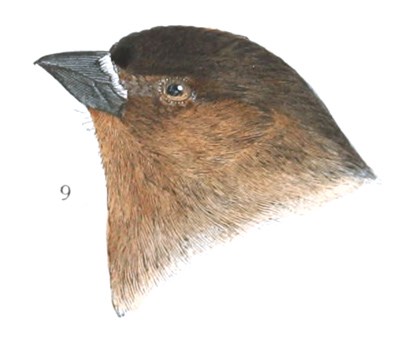

8. Leucosticte tephrocotis. Nebraska, 10225. Winter.

9. Leucosticte tephrocotis. Colorado. Summer.

10. Leucosticte arctous. Siberia, 9244.

11. Pyrrhula cassini. ♂ Alaska (Nulato), 49955.

12. Pyrgita domestica. Europe.

In the intensity, as well as the shade of the red in the males, there is a great range of variation. Generally it is of a tint almost precisely like that of L. curvirostra, though deeper. The most highly colored specimen is 54,795, Philadelphia (J. H. McIlvaine), which is entirely continuous deep tile-red, approaching vermilion on the rump. The abdomen and crissum are light pinkish. In No. 31,459, Fort Rae, April, the red is of a curious and very unusual purplish wine-red shade.

The average of western specimens, particularly those from the northwest coast of the United States, have bills scarcely larger than in the average of eastern examples; thus, 18,037, Fort Crook, N. Cal., has the bill of the same size as No. 5,803, Philadelphia, while No. 53,482, East Humboldt Mountains, has the bill smaller than any other in the collection.

In color, there are scarcely any tangible differences between the European Loxia curvirostra and the two American varieties, the distinctive character being in the form of the bill and the size; the C. mexicana is the largest of the three, and the bill is quite peculiar in form, the lower mandible almost equalling the upper in length, and exceeding it in thickness. L. curvirostra is slightly smaller, and has the lower mandible much smaller and less, powerful than the upper, being inferior to it both in length, breadth, and thickness. The colors also appear to be rather less intense than in C. mexicana.

The C. americana is in every way, the bill especially, smaller than either of the preceding. The lower mandible, although but slightly shorter than the upper, is still much weaker, as in the European bird. The majority of western birds have the bill but slightly larger than eastern, and most of those with large bills are only intermediate between americana and mexicana. In some specimens the bill, although almost equalling in length that of the latter, has yet the form of the former; on the other hand, there are specimens with the proportions of the mandibles as in mexicana, while the size is intermediate.

The following figures will illustrate the differences in the size of the bills of the different races.

1 Var. mexicana. 29703 ♂, Mexico.

2 Var. curvirostra. 17010 ♂, Europe.

3 Var. americana. 18036 ♂, California.

4 Var. americana. 5803 ♂, Philadelphia.

Specimens from the Columbia River region and northwest coast of the United States appear to have the red more rosaceous and the bill more slender than the typical style. One specimen (No. 31,459, Fort Rae) is altogether a very peculiar one; the shade of red is different from that of any other specimen, being a dark maroon-carmine, with a clear ash suffusion on the back. There are two distinct dusky stripes on the cheek, one over the upper edge of the ear-coverts, the other along the lower edge. The lining of the wing is without any red tinge, seen in all specimens of the true americana and mexicana; the wings and tail are pure sepia-brown, quite different from the others; and the feathers show no red margins. The lower mandible is very much curved. (May not this be like some Siberian style?)

No 21,868, from Washington Territory, has the bill nearly as slender as in C. leucoptera, but there is nothing else peculiar.

Habits. The common Red Crossbill of America is a bird of very irregular distribution, abundant in some places at certain seasons, and again rarely seen for several years. It is a Northern species, found in summer chiefly in the more northern portions of the United States, and also found throughout the year in the Alleghanies, in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, to Georgia. A closely allied variety is also found in the alpine regions of Vera Cruz and other departments of Mexico.

Dr. Suckley found this species quite abundant at Puget Sound, in certain seasons. This was especially so in the spring of 1854, though afterwards he met with but few. He noticed a pair on the ground near a pool of rain-water. They were very tame, and allowed a near approach. Dr. Cooper found it very abundant near the coast, where it feeds, in winter, on the seeds of the black spruce, retiring in summer to the mountains to breed, but returning in September. He never observed any in the fir forests of the Coast Range. In the Sierra Nevada, latitude 39°, Dr. Cooper found these birds in considerable numbers, September, 1863, and in winter they have been obtained about San Francisco. They seem to be most attracted to the forests of spruces, cypresses, and red-woods, the cones of which are most readily broken. They occasionally descend to the ground, in the Rocky Mountains, in search of the seeds of small plants, and also for water.

Mr. Bischoff obtained specimens of this species at Sitka, but it was not noticed in the territory of the Yukon River by Mr. Dall, or any of his party, and it was met with by Mr. Ridgway on the East Humboldt Mountains only. There they were occasionally seen among the willows and small aspens bordering the streams. Their common note was a fine and frequently repeated chick-chick-chick, very different from the plaintive notes of the C. leucoptera.

In New England they are of somewhat irregular occurrence, though in Maine and in the northern portions of Vermont and New Hampshire they are more or less resident. In Eastern Massachusetts they are comparatively rare, excepting that, at irregular intervals, they come in large flocks during the winter. This was so to a remarkable degree in the winter of 1832, and more recently in 1862, when, Mr. Maynard states, they remained until April. They were then in their summer plumage, and also in full song. In August 1868, they again became quite numerous, and had just before appeared in large numbers in Western Maine, doing great damage to the oats, and disappearing as soon as these had been harvested. Mr. Maynard thinks that these birds were the same with those afterwards so numerous in Massachusetts.

The same peculiarities of irregular appearance have been observed by Mr. Allen, in Springfield, where it is often a very abundant visitor, but generally not so common. In the winter of 1859-60 the pine woods in the vicinity of that city abounded with them, and in February they were already in full song. They are at all times gregarious, and are sometimes seen in large flocks.

They have, as they fly, a loud, peculiar, and not unmusical cry. This call-note they do not utter when at rest or when feeding. Their song in the spring and summer is varied and pleasing, but is not powerful, or in any respect remarkable. This song is especially noticeable in caged birds, who soon become very tame, and feed readily from the hand, even when taken at an adult age. Their manners in confinement are very like those of the Parrots, clinging to the top of the wires with their claws, hanging with their heads downward, and, when feeding, holding their food in one claw. On the trees, their habits and manner are also said to be similar to those of Parrots.

Mr. Audubon has found these birds, in August, in the pine woods of Pennsylvania, and inferred that they breed there. This does not necessarily follow. They breed so early at the north as to give ample time for their migrations, even in midsummer, to remote places. Professor Baird, however, informs me that during a summer spent in the mountains of Schuylkill County, Penn., in the coal region, he saw them nearly every day, moving about or feeding, in pairs.

The Crossbills are extremely gentle and social, are easily approached, caught in traps, and even knocked down with sticks. Their food is chiefly the seeds of the Coniferæ, and also those of plants. Audubon’s statement that they destroy apples merely to secure the seeds is hardly accurate. They are extravagantly fond of this fruit, and prefer the flesh to its seeds. Their flight is undulating, somewhat in the manner of the Goldfinch, firm, swift, and often protracted. As they fly, they always keep up the utterance of their loud, clear call-notes. They move readily on the ground, up or down the trunks and limbs of trees, and stand as readily with their heads downward as upright.

Wilson states that in the interior of Pennsylvania this species appears in large flocks in the winter, and during the prevalence of deep snows they keep about the doors of dwellings, pick off the clay with which these huts are plastered, and are exceedingly tame and not easily driven off.

So far as is known, these Crossbills breed in midwinter, or very early in the spring, when the weather is the most inclement. The nest and eggs of this species were procured by Mr. Charles S. Paine, in East Randolph, Vt., early in the month of March. The nest was built in an upper branch of an elm,—which, of course, was leafless,—the ground was covered with snow, and the weather severe. The birds were very tame and fearless, refusing to leave their eggs, and had to be several times taken off by the hand. After its nest had been taken, and as Mr. Paine was descending with it in his hand, the female again resumed her place upon it, to protect her eggs from the biting frost. The eggs were four in number, and measured .85 by .53 of an inch. They have a greenish-white ground and are beautifully blotched, marbled, and dotted with various shades of lilac and purplish-brown.

Loxia curvirostra, var. mexicana, StricklandMEXICAN CROSSBILLLoxia mexicana, Strickland, Jardine Contrib. Orn. 1851, 43.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1859, 365.—Ib. 1864, 174, City of Mexico.—Salvin, Ibis, 1866, 193 (Guatemala).

Sp. Char. Colors of americana, but red brighter, more scarlet. Bill very large, the lower mandible nearly or quite equal to the upper in strength and length. Wing, 4.00; tail, 2.50; bill (from forehead) .82.

Hab. Mountainous regions of Southern North America, from Guatemala, north into Rocky Mountains of United States; Mexico, Orizaba.

This bird is quite as well marked as any of the plain-winged “species,” differing from curvirostra and americana quite as much as they do from each other.

All specimens from Mexico, as well as from the Central Rocky Mountains of the United States, are referrible to this form, though in winter the americana may also be found in the latter region, as a migrant from the north.

Habits. The occurrence of this well-marked race among the mountainous districts of Mexico is a very interesting and suggestive fact in regard to the distribution of birds, demonstrating, as it does, the close connection between high latitudes and high elevations as favoring similar forms. It was first described by Strickland from specimens obtained on the plateau near the city of Mexico. Another specimen is referred to by Mr. Sclater as having been received from Jalapa, Mexico; and Mr. Sumichrast obtained also a single specimen of this species at Moyoapam, in the alpine region of Orizaba, where it is known as the Pico cruzado. It was taken at an elevation of about 7,500 feet. Mr. Sumichrast was unable to determine whether this bird was resident, or only a migratory visitant in the winter. I can find no reference to any distinctive peculiarities of habits.

Loxia leucoptera, GmelinWHITE-WINGED CROSSBILLLoxia, leucoptera, Gm. Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 540.—Aud. Orn. Biog. IV, 1838, 467, pl. ccclxiv.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 190, pl. cci.—Bon. & Schl. Mon. Loxiens, 1850, 8, pl. ix.—Gould, B. Gt. Britain, V, 1864 (killed England, Sept. 17). Curvirostra leucoptera, Wils. Am. Orn. IV, 1811, 48, pl. xxxi, f. 3.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 427.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. Ac. I, 1869, 281 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 149.—Samuels, 293. Crucirostra leucoptera, Brehm, Naumannia, I, 1853, 254, fig. 20. Loxia falcirostra, Lath. Index, Orn. I, 1790, 371.

Sp. Char. Bill greatly compressed, and acute towards the point. Male carmine red, tinged with dusky across the back; the sides of body under the wings streaked with brown; from the middle of belly to the tail-coverts whitish, the latter streaked with brown. Scapulars, wings, and tail black; two broad bands on the wings across the ends of greater and median coverts; white spots on the end of the inner tertiaries. Female brownish, tinged with olive-green in places; feathers of the back and crown with dusky centres; rump bright brownish-yellow. Length about 6.25; wing, 3.50; tail, 2.60.

Hab. Northern parts of North America generally; Greenland (Reinh. Ibis, III, 1861, 8); England, (September 17, Gould, Birds Great Britain).

The white bands on the wings distinguish this species from the preceding, although there are some other differences in form of bill, feet, wing, etc. There is less variation in form and color among specimens than in the preceding. It differs from the European analogue, L. bifasciata, according to authors, in the more slender body and bill, and in having the body pomegranate-red, with blackish back, instead of cinnabar-red, as in curvirostra and americana, Bonaparte and Schlegel quote the American species as occurring in the Himalaya Mountains, and perhaps Japan, but throw doubts on the supposed European localities.

Habits. Both the distribution and habits of this species are probably, in all essential respects, the same with those of the preceding. It is, if anything, a more northern bird, and it has not been detected anywhere on the Pacific coast south of British America. It was found in the Arctic regions by Sir John Richardson, where the other species was not observed. He found it inhabiting the dense white-spruce forests of the fur country, feeding principally on the seeds of their cones. Up to the sixty-eighth parallel he found them ranging through the whole breadth of the continent. It is supposed to go as far as these woods extend, though it has not been traced farther than the sixty-second degree. It was found feeding on the upper branches, clinging to them when wounded, and remaining suspended even after death. In September they collected in small flocks, and flew from tree to tree with a chattering noise. In the depth of winter they retire from the coast to the thick woods of the interior.

A few individuals of this species are recorded by Professor Reinhardt as having been taken in South Greenland.

In Pennsylvania this species is much more rare than the americana, and Wilson only met with a few specimens. Since his day it has been found more abundantly, occasionally in the neighborhood of Philadelphia.

Mr. Dall states that these birds were not uncommon near Nulato in the winter. Several specimens were obtained in February and April. None were found there in the summer. He speaks of their great expertness in opening the spruce cones with their curved bills, and extracting the seeds.

Its appearance in Eastern Massachusetts is much more irregular both as to numbers and time than that of the other species. In the fall and winter of 1868 and 1869 they were uncommonly abundant, appearing early in the fall, and remaining until quite late in the spring. They were even more fearless and tame than the americana, and in one instance a pair were taken by the hand, and afterwards kept in confinement. They appeared around Boston in large flocks, and remained through April. One was shot in Newton by Mr. Maynard, June 13. It was found in an apple-tree, and its crop was full of canker-worms. In Eastern Maine it is resident throughout the year, and, like the other species, breeds in winter. In Western Maine Professor Verrill has found it a common winter visitant, but it is not known to be resident.