полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

The egg resembles that of the other, but is more spherical and of a much darker shade of green. The color is equally fugitive, and even in a closed cabinet fades so that the eggs of the two species are undistinguishable, except in size and shape. This egg averages 1.10 inches in length by .90 of an inch in breadth.

Genus CROTOPHAGA, LinnæusCrotophaga, Linnæus, Systema Naturæ, 1756. (Type, C. ani, Linn.).

Gen. Char. Bill as long as the head, very much compressed; the culmen elevated into a high crest, extending above the level of the forehead. Nostrils exposed, elongated. Point of bill much decurved. Wings lengthened, extending beyond the base of the tail, the fourth or fifth quill longest. Tail lengthened, of eight graduated feathers. Toes long, with well-developed claws.

The feathers in this genus are entirely black; those on the head and neck with a peculiar stiffened metallic or scale-like border. The species are not numerous, and are entirely confined to America.

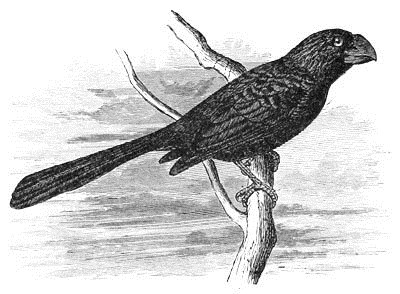

Crotophaga ani.

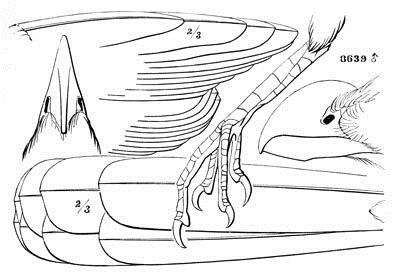

8639 ♂

Of Crotophaga, two species have heretofore been recognized in the United States, C. ani and C. rugirostris. We are, however, satisfied that there is but one here and in the West Indies, C. ani (extending to South America). C. major of South America, and C. sulcirostris, found from Mexico southward, are the other species, and are easily distinguishable by the following characters among others:—

C. major. 122 Length, 17.00; wing, 7.50; outline of culmen abruptly angulated in the middle. Hab. Brazil and Trinidad.

C. ani. Length, 13.00 to 15.00; wing, 6.00; culmen gently curved from base. Bill smooth or with a few transverse wrinkles. Hab. Northeastern South America, West Indies, and South Florida.

C. sulcirostris. 123 Length, 12.00; wing, 5.00; culmen gently curved. Bill with several grooves parallel to culmen. Hab. Middle America, from Yucatan, south to Ecuador.

Crotophaga ani, LinnTHE ANI; THE SAVANNA BLACKBIRDCrotophaga ani, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 154.—Burmeister, Th. Bras. (Vögel.) 1856, 254.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 72, pl. lxxxiv, f. 2.—Cabanis, Mus. Hein. IV, 100. Crotophaga minor, Less. Traité Orn. 1831, 130. Crotophaga lævirostra, Swainson, An. in Menag. 2¼ Cent. 1838, 321. Crotophaga rugirostra, Swainson, 2¼ Cent. 1838, 321, fig. 65, bill.—Burm. Th. Bras. II, 1856, 235.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 71, pl. lxxxiv, f. 1.

Crotophaga ani.

Sp. Char. Bill at the nostrils nearly twice as high as broad; the nostrils elliptical, a little oblique, situated in the middle of the lower half of the upper mandible. Gonys nearly straight. Indications of faint transverse wrinkles along the upper portion of the bill, nearly perpendicular to the culmen. Legs stout; tarsus longer than middle toe, with seven broad scutellæ anteriorly extending round to the middle of each side; the remaining or posterior portion of each side with a series of quadrangular plates, corresponding nearly to the anterior ones, the series meeting behind in a sharp ridge. The wings reach over the basal third of the tail. The primary quills are broad and acute, the fourth longest; the first about equal to the tertials. The tail is graduated, the outer about an inch and a half shorter than the middle ones.

The color generally is black, with steel-blue reflections above, changing sometimes into violet; duller beneath. The pointed feathers of the head, neck, and breast, with a bronzy metallic border, appearing also to some extent on the wing-coverts and upper part of back. Iris brown. Length, 13.20; wing, 6.00; tail, 8.30; tarsus, 1.48.

Hab. West Indies; South Florida. Accidental near Philadelphia. Localities: Sta. Cruz (Newton, Ibis, I, 148).

As already remarked, we do not find reason to admit more than one species of Crotophaga in the United States and the West Indies, as in the great variation in size, and to some extent in shape of bill, there is nothing constant. The species can hardly be considered more than a straggler in the United States, although a considerable number of specimens have been seen or taken within its limits. That in the Smithsonian collection was killed on the Tortugas; but there is one in the collection of the Philadelphia Academy, killed near Philadelphia by Mr. John Krider, and presented by him. Mr. Audubon also possessed a pair said to have been killed near New Orleans.

Habits. This species, the common Savanna Blackbird of the West India Islands, is probably only an accidental visitant of the United States, and may not strictly belong to the avi-fauna of North America.

It is common throughout the West Indies, and in South America as far south as Brazil. Gosse states it to be one of the most abundant birds of Jamaica. In speaking of its breeding habits he mentions that it was universally maintained by the inhabitants that these birds unite and build in company an immense nest of basket-work, made by the united labors of the flock. This is said to be placed on a high tree, where many parents bring forth and educate a common family. This statement is reiterated by Mr. Hill, who says that a small flock of about six individuals build but one large and capacious nest, to which they resort in common, and rear their young together.

In July Mr. Gosse found the nest of one of these birds in a guazuma tree. It was a large mass of interwoven twigs, and was lined with leaves. There were eight eggs in the nest, and the shells of many others were scattered beneath the tree.

Mr. Newton found these birds very common in St. Croix. He mentions meeting with a nest of this species June 17. It was about five feet from the ground, on a large tamarind-tree. He speaks of it as a rude collection of sticks and twigs, large and deep, partly filled with dry leaves, among which were fourteen eggs, and around the margin were stuck upright a few dead twigs of tamarind. Five days afterwards he went to the nest, where he found but nine eggs, two of which he took. Three days later he found but four eggs in the nest, it having been robbed in the interim; but six days afterwards the number had again been increased to eight. He never found the eggs covered up as if intentionally done. The nest was evidently common property. There were generally two or three birds sitting close to or on it, and up in the tree perhaps four or five more, who would continue screeching all the time he was there. Mr. Newton adds that when the egg is fresh the cretaceous deposit on the shell is very soft and easily scored, but it soon hardens. It is mentioned in De Sagra’s list as one of the common birds of Cuba.

Mr. J. F. Hamilton, in his interesting paper (Ibis, July, 1871) on the birds of Brazil, mentions finding this species very common at Santo Paulo. There was scarcely an open piece of ground where there were but few bushes that had not its flock of these birds. They were especially fond of marshy ground. They were also often to be seen running about among a herd of cattle, picking up the insects disturbed by the animals. They seemed utterly regardless of danger, and would scarcely do more than flit from one bush to another, even when the numbers of their flock were being greatly thinned. When concealed in the long grass, they would allow themselves to be almost trodden on before rising. The Brazilians seldom molest them, as their flesh is not good to eat.

This bird is known as the Black Witch in St. Croix,—a name Mr. Newton supposes to be due to its peculiar call-note, which sounds like que-yuch. Its familiar habits and its grotesque appearance make it universally known. It is a favorite object of attack to the Chickaree Flycatcher, in which encounters it is apt to lose its presence of mind, and to be forced to make an ignominious retreat.

These birds are said to be attracted by collections of cattle and horses, upon the bodies of which they are often seen to alight, feeding upon the ticks with which they are infested. They are at once familiar and wary, permitting a limited acquaintance, but a too near approach sets the whole flock in motion. It moves in a very peculiar gliding flight. In feeding it is omnivorous; besides insects of all kinds, such as ticks, grasshoppers, beetles, etc., it eats berries of various kinds, lizards, and other kinds of food. It catches insects on the ground by very active jumps, pursues them on the wing, and with its sharp thin bill digs them out in the earth. They hop about and over the bodies of cattle, especially when they are lying down, and when grazing they have been observed clinging to a cow’s tail, picking insects from it as far down even as its extremity.

Mr. Hill states that these birds are downward, not upward, climbers. They enter a tree by alighting on the extremity of some main branch, and reach its centre by creeping along the stem, and seldom penetrate far among the leaves.

The eggs of this species are of a regularly oval shape, equally obtuse at either end. In color they are of a uniform light-blue, with a very slight tinge of green. This is usually covered, but not entirely concealed, by a white cretaceous coating. When fresh, this may readily be rubbed off, but becomes hard and not easily removed. The eggs vary in size from 1.40 to 1.50 inches in length, and in breadth from 1.10 to 1.15 inches.

Family PICIDÆ.—The Woodpeckers

Char. Outer toe turned backwards permanently, not versatile laterally, the basal portion of the tongue capable of great protrusion.

The preceding characters combined appear to express the essential characters of the Picidæ. In addition, it may be stated that the tongue itself is quite small, flat, and short, acute and horny, usually armed along the edges with recurved hooks. The horns of the hyoid apparatus are generally very long, and curve round the back of the skull, frequently to the base of the bill, playing in a sheath, when the tongue is thrown forward out of the mouth to transfix an insect.

There are twelve tail-feathers, of which the outer is, however, very small and rudimentary (lying concealed between the outer and adjacent feathers), so that only ten are usually counted. The tail is nearly even, or cuneate, never forked, the shafts very rigid in the true Woodpeckers; soft in Picumninæ and Yunginæ. The outer primary is generally very short, or spurious, but not wanting. The bill is chisel or wedge shaped, with sharp angles and ridges and straight culmen; sometimes the culmen is a little curved, in which case it is smoother, and without the ridges. The tarsi in the North American forms are covered with large plates anteriorly, posteriorly with small ones, usually more or less polygonal. The claws are compressed, much curved, very strong and acute.

The Picidæ are found all over the world with the exception of Madagascar, Australia, the Moluccas, and Polynesia. America is well provided with them, more than half of the described species belonging to the New World.

The subfamilies of the Picidæ may be most easily distinguished as follows, although other characters could readily be given:—

Picinæ. Tail-feathers pointed, and lanceolate at end; the shafts very rigid, thickened and elastic.

Picumninæ. Tail soft and short, about half the length of wing; the feathers without stiffened shafts, rather narrow, linear, and rounded at end.

Yunginæ. Tail soft and rather long, about three fourths the length of wing; the feathers broad, and obtusely rounded at end.

Of these subfamilies the Picinæ alone occur north of Mexico. The Yunginæ, to which the well-known Wryneck of England (Jynx torquilla) belongs, are exclusively Old World; the Picumninæ belong principally to the tropical regions of America, although a few species occur in Africa and India. One species, Picumnus micromegas, Sundevall, belongs to St. Domingo, although erroneously assigned to Brazil. This is the giant of the group, being about the size of the White-bellied Nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis) the other species being mostly very diminutive, varying from three to four inches in length.

Subfamily PICINÆ

The diagnosis on the preceding page will serve to distinguish this group from its allies, without the necessity of going into greater detail. It includes by far the largest percentage of the Picidæ, and in the great variations of form has been variously subdivided by authors into sections. Professor Sundevall, in his able monograph,124 establishes the following four series, referring all to the single genus Picus:—

I. Angusticolles. Neck slender, elongated. Nostrils concealed by bristles. Tail-feathers black or brownish, immaculate.

II. Securirostres. Neck not slender, and shorter. Nostrils concealed by bristles. Bill stout, cuneate, with the nasal ridges widely distant from each other.

III. Ligonirostres. Neck not slender. Nostrils covered, nasal ridges of bill placed near the culmen (or at least nearer it than the lower edge of the upper mandible), for the most part obsolete anteriorly.

IV. Nudinares. Nostrils open, uncovered by bristly hairs. Neck and bill various.

Of these series, the first and second correspond with Piceæ, as given below, while Centureæ and Colapteæ both belong to Ligonirostres. The Nudinares are not represented in North America, and by only one group, Celeus, in any portion of the continent.

In the following account of the Picinæ, we shall not pretend to discuss the relationship of the North American species to the Picinæ in general, referring to Sundevall’s work, and the monographs of Malherbe and Cassin, for information on the subject. For our present purposes they may be conveniently, even if artificially, arranged in the following sections:—

Piceæ. Bill variable in length; the outlines above and below nearly straight; the ends truncated; a prominent ridge on the side of the mandible springing from the middle of the base, or a little below, and running out either on the commissure, or extending parallel to and a little above it, to the end, sometimes obliterated or confluent with the lateral bevel of the bill. Nostrils considerably overhung by the lateral ridge, more or less linear, and concealed by thick bushy tufts of feathers at the base of the bill. Outer posterior toe generally longer than the anterior.

Centureæ. Bill rather long; the outlines, that of the culmen especially, decidedly curved. The lateral ridge much nearest the culmen, and, though quite distinct at the base, disappearing before coming to the lower edge of the mandible; not overhanging the nostrils, which are broadly oval, rounded anteriorly, and not concealed by the bristly feathers at the base. Outer pair of toes nearly equal; the anterior rather longer.

Colapteæ. Bill rather long, much depressed, and the upper outline much curved to the acutely pointed (not truncate) tip. The commissure considerably curved. Bill without any ridges. The nostrils broadly oval, and much exposed. Anterior outer toe longest.

PLATE XLVIII.

1. Geococcyx californianus ♂ Cal., 12925.

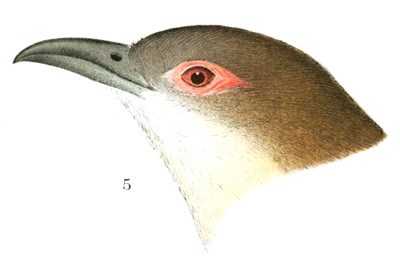

2. Crotophaga ani. ♀ Fla., 8639.

3. Coccygus americanus. ♂ Penn., 1541.

4. Coccygus minor.

5. Coccygus erythrophthalmus. 27028.

The preceding diagnoses will serve to distinguish the three groups sufficiently for our present purposes; the bill being strongest in the Picinæ and best fitted for cutting into trees by its more perfect wedge-shape, with strengthening ridges, as well as by the lateral bevelling of both mandibles, which are nearly equal in thickness at the base, and with their outlines nearly straight. The lateral ridge is prominent, extending to the edge or end of the bill, and overhangs the nostrils, which are narrow and hidden. The Centureæ and the Colapteæ have the upper mandible more curved (the commissure likewise), the lower mandible smaller and weaker, the bill with little or no lateral bevelling. The nostrils are broadly oval and exposed. In the former, however, there is a distinct lateral ridge visible for a short distance from the base of the bill; while in the other there is no ridge at all, and the mandible is greatly curved.

In all the species of North American Woodpeckers, there is more or less red on the head in the male, and frequently in the female. The eggs of all are lustrous polished white, without any markings, and laid in hollow trees, upon a bed of chips, no material being carried in for the construction of the nest.

Section PICEÆWith the common characters, as already given, there are several well-marked generic groups in this section of Woodpeckers which may be arranged for the United States species as follows:—

A. Posterior outer toe longer than the anterior outer one. (Fourth toe longer than third.)

a. Lateral ridge starting above the middle of the base of the bill, and extending to the tip.

1. Campephilus. Lateral ridge above the middle of the lateral profile of the bill when opposite the end of the nostrils, which are ovate, and rounded anteriorly. Bill much depressed, very long; gonys very long. Posterior outer toe considerably longer than the anterior. Primaries long, attenuated towards the tip. Spurious quill nearly half the second. Shafts of four middle tail-feathers remarkably stout, of equal size, and abruptly very much larger than the others; two middle tail-feathers narrower towards bases than towards end.125 A pointed occipital crest.

2. Picus. Lateral ridge in the middle of the lateral profile opposite the end of the nostrils, which are ovate and sharp-pointed anteriorly. Bill moderate, nearly as broad as high.

Outer hind toe moderately longer than the outer fore toe. Primaries broad to the tip, and rounded. Spurious primary not one third the second quill.

3. Picoides. Lateral ridge below the middle of the profile, opposite the end of the ovate acute nostrils, which it greatly overhangs. Bill greatly depressed; lower mandible deeper than the upper. Inner hind toe wanting, leaving only three toes. Tufts of nasal bristles very full and long.

b. Lateral ridge starting below the middle of the base of the bill, and running as a distinct ridge into the edge of the commissure at about its middle; the terminal half of the mandible rounded on the sides, although the truncate tip is distinctly bevelled laterally.

4. Sphyropicus. Nostrils considerably overhung by the lateral ridge, very small, linear. Gonys as long as the culmen, from the nostrils. Tips of tail-feathers elongated and linear, not cuneate. Wings very long; exposed portion of spurious primary about one fourth that of second quill.

B. Posterior outer toe considerably shorter than the anterior outer one. (Fourth toe shorter than third).

5. Hylotomus. Bill depressed. Lateral ridge above the middle of the lateral profile near the base. Nostrils elliptical, wide, and rounded anteriorly. Tail almost as in Sphyropicus. A pointed occipital crest, as in Campephilus, and not found in the other genera.

The arrangement in the preceding diagnosis is perhaps not perfectly natural, although sufficiently so for our present purpose. Thus, Hylotomus, in having the lateral ridge extending to the end of the bill, is like Picus, but the nostrils are broader, more open, and not acute anteriorly. The tail-feathers of Sphyropicus differ greatly from those of the others in being abruptly acuminate, the points elongated, narrow, and nearly linear, instead of being gently cuneate at the ends. Campephilus and Hylotomus belong to Sundevall’s Angusticolles, with their long slender neck, and elongated occipital crest (Dryocopinæ, Cab.); the other genera to Securirostres, with shorter, thicker neck, and no crest (Dendrocopinæ, Cab.). But no two genera in the subfamily are more distinct than Campephilus and Hylotomus.

Genus CAMPEPHILUS, GrayCampephilus, Gray, List of Genera? 1840. (Type, C. principalis.)

Megapicus, Malherbe, Mém. Ac. de Metz, 1849, 317.

Gen. Char. Bill considerably longer than the head, much depressed, or broader than high at the base, becoming somewhat compressed near the middle and gradually bevelled off at the tip. Culmen very slightly curved, gonys as concave, the curve scarcely appreciable; commissure straight. Culmen with a parallel ridge on each side, starting a little above the centre of the basal outline of the bill, the ridge projecting outwards and downwards, and a slight concavity between it and the acute ridge of the culmen. Gonys considerably more than half the commissure. Nostrils oval below the lateral ridge near the base of the bill; concealed by the bristly feathers directed forward. Similar feathers are seen at the sides of the lower jaw and on the chin.

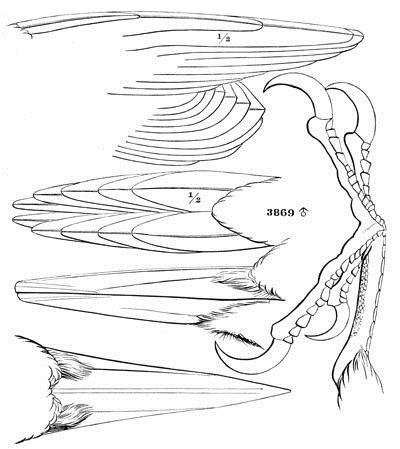

Campephilus principalis.

3869 ♂

Feet large; outer hind toe much longest; claw of inner fore toe reaching to middle of outer fore claw; inner hind toe scarcely more than half the outer one; its claw reaching as far as the base of the inner anterior claw, considerably more than half the outer anterior toe. Tarsus rather shorter than the inner fore toe. Tail long, cuneate; shafts of the four middle feathers abruptly much larger than the others, and with a deep groove running continuously along their under surface; webs of the two middle feathers deflected, almost against each other, so that the feathers appear narrower at the base than terminally. Wings long and pointed, the third, fourth, and fifth quills longest; sixth secondary longest, leaving six “tertials,” instead of three or four as usual; primaries long, attenuated. Color continuous black, relieved by white patches. Head with a pointed occipital crest.

This genus embraces the largest known kind of Woodpecker, and is confined to America. Of the two species usually assigned to it, only one occurs within the limits of the United States, C. imperialis, given by Audubon, and by subsequent authors on his credit, really belonging to Southern Mexico and Central America. The diagnoses of the species are as follows:—

Common Characters. Bill ivory-white. Body entirely glossy blue-black. A scapular stripe, secondaries, ends of inner primaries, and under wing-coverts, white. Crest scarlet in the male, black in the female.

1. C. principalis. A white stripe on each side of the neck. Bristly feathers at the base of the bill white.

White neck-stripe not extending to the base of the bill. Black feathers of crest longer than the scarlet. Wing, 10.00; culmen, 2.60. Hab. Gulf region of United States … var. principalis.

White stripe reaching the base of the bill. Scarlet feathers of crest longer than the black. Wing, 9.50; culmen, 2.40. Hab. Cuba … var. bairdi.126