полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

When their contests are ended, and the mated pair take possession of their selected meadow, and prepare to construct their nest and rear their family, then we may find the male bird hovering in the air over the spot where his homely partner is brooding over her charge. All this while he is warbling forth his incessant and happy love-song; or else he is swinging on some slender stalk or weed that bends under him, ever overflowing with song and eloquent with melody. As domestic cares and parental responsibilities increase, his song becomes less and less frequent. After a while it has degenerated into a few short notes, and at length ceases altogether. The young in due time assume the development of mature birds, and all wear the sober plumage of the mother. And now there also appears a surprising change in the appearance of our gayly attired musician. His showy plumage of contrasting white and black, so conspicuous and striking, changes with almost instant rapidity into brown and drab, until he is no longer distinguishable, either by plumage or note, from his mate or young.

At the north, where the Bobolinks breed, they are not known to molest the crops, confining their food almost entirely to insects, or the seeds of valueless weeds, in the consumption of which they confer benefit, rather than harm. At the south they are accused of injuring the young wheat as they pass northward in their spring migrations, and of plundering the rice plantations on their return. About the middle of August they appear in almost innumerable flocks among the marshes of the Delaware River. There they are known as Reedbirds. Two weeks later they begin to swarm among the rice plantations of South Carolina. There they take the name of Ricebirds. In October they again pass on southward, and make another halt among the West India Islands. There they feed upon the seeds of the Guinea-grass, upon which they become exceedingly fat. In Jamaica they receive a new appellation, and are called Butterbirds. They are everywhere sought after by sportsmen, and are shot in immense numbers for the table of the epicure. More recently it has been ascertained that these birds feed greedily upon the larvæ of the destructive cotton-worm, and in so doing render an immense service to the cultivators of Sea Island cotton.

Dr. Bryant, in his visit to the Bahamas, was eye-witness to the migrations northward of these birds, as they passed through those islands. He first noted them on the 6th of May, towards sunset. A number of flocks—he counted nine—were flying to the westward. On the following day the country was filled with these birds, and men and boys turned out in large numbers to shoot them. He examined a quantity of them, and all were males in full plumage. Numerous flocks continued to arrive that day and the following, which was Sunday. On Monday, among those that were shot were many females. On Tuesday but few were to be seen, and on Wednesday they had entirely disappeared.

Near Washington, Dr. Coues observed the Bobolink to be only a spring and autumnal visitant, from May 1st to the 15th distributed abundantly about orchards and meadows, generally in flocks. In autumn they frequented in immense flocks the tracts of Zizania aquatica, along the Potomac, from August 20 to October.

The Bobolink invariably builds its nest upon the ground, usually in a meadow, and conceals it so well among the standing grass that it is very difficult of discovery until the grass is cut. The female is very wary in leaving or in returning to her nest, always alighting upon the ground, or rising from it, at a distance from her nest. The male bird, too, if the nest is approached, seeks to decoy off the intruder by his anxiety over a spot remote from the object of his solicitude. The nest is of the simplest description, made usually of a few flexible stems of grasses carefully interwoven into a shallow and compact nest. The eggs, five or six in number, have a dull white ground, in some tinged with a light drab, in others with olive. They are generally spotted and blotched over the entire egg with a rufous-brown, intermingled with lavender. They are pointed at one end, and measure .90 by .70 of an inch. They have but one brood in a season.

In some eggs, especially those found in more northern localities, the ground-color is drab, with a strong tinge of purple. Over this is diffused a series of obscure lavender-color, and then overlying these are larger and bolder blotches of wine-colored brown. In a few eggs long and irregular lines of dark purple, so deep as to be undistinguishable from black, are added. These eggs are quite pointed at one end.

Genus MOLOTHRUS, SwainsonMolothrus, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 277; supposed by Cabanis to be meant for Molobrus. (Type, Fringilla pecoris, Gm.)

Molothrus pecoris.

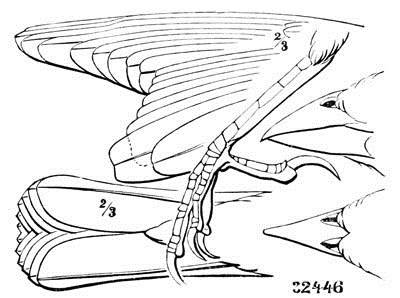

32446

Gen. Char. Bill short, stout, about two thirds the length of head; the commissure straight, culmen and gonys slightly curved, convex, the former broad, rounded, convex, and running back on the head in a point. Lateral toes nearly equal, reaching the base of the middle one, which is shorter than tarsus; claws rather small. Tail nearly even; wings long, pointed, the first quill longest. As far as known, the species make no nest, but deposit the eggs in the nests of other, usually smaller, birds.

The genus Molothrus has the bill intermediate between Dolichonyx and Agelaius. It has the culmen unusually broad between the nostrils, and it extends back some distance into the forehead. The difference in the structure of the feet from Dolichonyx is very great.

Molothrus pecoris.

Species of Molothrus resemble some of the Fringillidæ more than any other of the Icteridæ. The bill is, however, more straight, the tip without notch; the culmen running back farther on the forehead, the nostrils being situated fully one third or more of the total length from its posterior extremity. This is seldom the case in the American families. The entire absence of notch in the bill and of bristles along the rictus are strong features. The nostrils are perfectly free from any overhanging feathers or bristles. The pointed wings, with the first quill longest, or nearly equal to second, and the tail with its broad rounded feathers, shorter than the wings, are additional features to be specially noted.

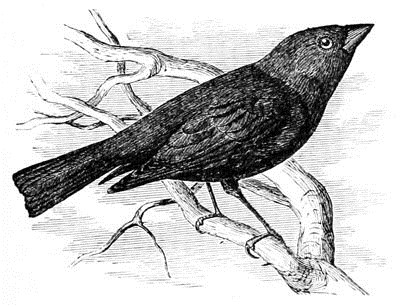

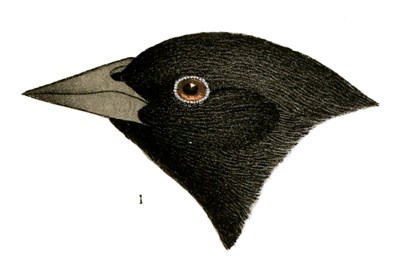

Molothrus pecoris, SwainsonCOW BLACKBIRD; COWBIRDFringilla pecoris, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 910 (female).—Lath. Ind. Orn. I, 1790, 443.—Licht. Verzeich. 1823, Nos. 230, 231. Emberiza pecoris, Wils. Am. Orn. II, 1810, 145, pl. xviii, f. 1, 2, 3. Icterus pecoris, Bonap. Obs. Wilson, 1824, No. 88.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1831, 493; V, 1839, 233, 490, pls. xcix and ccccxxiv. Icterus (Emberizoides) pecoris, Bon. Syn. 1828, 53.—Ib. Specchio comp. No. 41.—Nutt. Man. I, 1832, 178, (2d ed.,) 190. Passerina pecoris, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. XXV, 1819, 22. Psarocolius pecoris, Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 20. Molothrus pecoris, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 277.—Rich. List, 1837.—Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Consp. 1850, 436.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 139.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 16, pl. ccxii.—Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 193.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 524.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 257.—Samuels, 339.—Allen, B. Fla. 284. ? Oriolus fuscus, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 393. ? Sturnus obscurus, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 804 (evidently a Molothrus, and probably, but not certainly, the present species). Molothrus obscurus, Cassin, Pr. Ph. Ac. 1866, 18 (Mira Flores, L. Cal.).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 260. “Icterus emberizoides, Daudin.” ? Sturnus junceti, Lath. Ind. I, 1790, 326 (same as Sturnus obscurus, Gm.). ? Fringilla ambigua, Nuttall, Man. I, 1832, 484 (young). Sturnus nove-hispaniæ, Briss. II, 448.

Sp. Char. Second quill longest; first scarcely shorter. Tail nearly even, or very slightly rounded. Male with the head, neck, and anterior half of the breast light chocolate-brown, rather lighter above; rest of body lustrous black, with a violet-purple gloss next to the brown, of steel blue on the back, and of green elsewhere. Female light olivaceous-brown all over, lighter on the head and beneath. Bill and feet black. Length, 8 inches; wing, 4.42; tail, 3.40.

Hab. United States from the Atlantic to California; not found immediately on the coast of the Pacific? Orizaba (Scl. 1857, 213); Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 492); Fort Whipple, Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S., 1866, 90); Nevada and Utah (Ridgway); Mazatlan, Tehuantepec, Cape St. Lucas.

The young bird of the year is brown above, brownish-white beneath; the throat immaculate. A maxillary stripe and obscure streaks thickly crowded across the whole breast and sides. There is a faint indication of a paler superciliary stripe. The feathers of the upper parts are all margined with paler. There are also indications of light bands on the wings. These markings are all obscure, but perfectly appreciable, and their existence in adult birds of any species may be considered as embryonic, and showing an inferiority in degree to the species with the under parts perfectly plain.

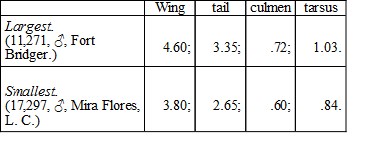

Specimens from the west appear to have a rather longer and narrower bill than those from the east. Summer birds of Cape St. Lucas and the Rio Grande are considerably smaller (var. obscurus, Cassin). Length about 6.50; wing, 4.00; tail, 3.00. Some winter skins from the same region are equal in size to the average.

Birds of this species breeding south of the Rio Grande, as well as those from Cape St. Lucas, Mazatlan, etc., are very much smaller than those nesting within the United States; but the transition between the extremes of size is so gradual that it is almost impossible to strike an average of characters for two races. The extremes of size in this species are as follows:—

Habits. The common Cow Blackbird has a very extended distribution from the Atlantic to California, and from Texas to Canada, and probably to regions still farther north. They have not been traced to the Pacific coast, though abundant on that of the Atlantic. Dr. Cooper thinks that a few winter in the Colorado Valley, and probably also in the San Joaquin Valley.

This species is at all times gregarious and polygamous, never mating, and never exhibiting any signs of either conjugal or parental affections. Like the Cuckoos of Europe, our Cow Blackbird never constructs a nest of her own, and never hatches out or attempts to rear her own offspring, but imposes her eggs upon other birds; and most of these, either unconscious of the imposition or unable to rid themselves of the alien, sit upon and hatch the stranger, and in so doing virtually destroy their own offspring,—for the eggs of the Cowbird are the first hatched, usually two days before the others. The nursling is much larger in size, filling up a large portion of the nest, and is insatiable in its appetite, always clamoring to be fed, and receiving by far the larger share of the food brought to the nest; its foster-companions, either starved or stifled, soon die, and their dead bodies are removed, it is supposed, by their parents. They are never found near the nest, as they would be if the young Cow Blackbird expelled them as does the Cuckoo; indeed, Mr. Nuttall has seen parent birds removing the dead young to a distance from the nest, and there dropping them.

For the most part the Cowbird deposits her egg in the nest of a bird much smaller than herself, but this is not always the case. I have known of their eggs having been found in the nests of Turdus mustelinus and T. fuscescens, Sturnella magna and S. neglecta. In each instance they had been incubated. How the young Cowbird generally fares when hatched in the nests of birds of equal or larger size, and the fate of the foster-nurslings, is an interesting subject for investigation. Mr. J. A. Allen saw, in Western Iowa, a female Harporhynchus rufus feeding a nearly full grown Cowbird,—a very interesting fact, and the only evidence we now have that these birds are reared by birds of superior size.

It lays also in the nests of the common Catbird, but the egg never remains there long after the owner of the nest becomes aware of the intrusion. The list of the birds in whose nests the Cow Blackbird deposits her egg and it is reared is very large. The most common nurses of these foundlings in New England are Spizella socialis, Empidonax minimus, Geothlypis trichas, and all our eastern Vireos, namely, olivaceus, solitarius, noveboracensis, gilvus, and flavifrons. Besides these, I have found their eggs in the nests of Polioptila cærulea, Mniotilta varia, Helminthophaga ruficapilla, Dendroica virens, D. blackburniæ, D. pennsylvanica and D. discolor, Seiurus aurocapillus, Setophaga ruticilla, Cyanospiza cyanea, Contopus virens, etc. I have also known of their eggs having been found in the nests of Vireo belli and V. pusillus, and Cyanospiza amœna. Dr. Cooper has found their egg in the nest of Icteria virens; and Mr. T. H. Jackson of West Chester, Penn., in those of Empidonax acadicus and Pyranga rubra.

Usually not more than a single Cowbird’s egg is found in the same nest, though it is not uncommon to find two; and in a few instances three and even four eggs have been met with. In one instance Mr. Trippe mentions having found in the nest of a Black and White Creeper, besides three eggs of the owner of the nest, no less than five of the parasite. Mr. H. S. Rodney reports having found, in Potsdam, N. Y., May 15, 1868, a nest of Zonotrichia leucophrys of two stories, in one of which was buried a Cowbird’s egg, and in the upper there were two more of the same, with three eggs of the rightful owners. In the spring of 1869 the same gentleman found a nest of the Sayornis fuscus with three Cowbird’s eggs and three of her own.

Mr. Vickary, of Lynn, found, in the spring of 1860, the nest of a Seiurus aurocapillus, in which, with only one egg of the rightful owner, there were no less than four of the Cowbird. All five eggs were perfectly fresh, and had not been set upon. In the summer of the preceding year the same gentleman found a nest of the Red-eyed Vireo containing three eggs of the Vireo and four of the Cow Blackbird.

How the offspring from these eggs may all fare when more than one of these voracious nurslings are hatched in the same nest, is an interesting problem, well worthy the attention of some patiently inquiring naturalist to solve.

The Cow Blackbird appears in New England with a varying degree of promptness, sometimes as early as the latter part of March, and as frequently not until the middle of April. Nuttall states that none are seen in Massachusetts after the middle of June until the following October, and Allen, that they are there all the summer. My own observations do not correspond with the statement of either of these gentlemen. They certainly do become quite rare in the eastern part of that State after the third week in June, but that all the females are not gone is proved by the constant finding of freshly laid eggs up to July 1. I have never been able to find a Cow Blackbird in Eastern Massachusetts between the first of July and the middle of September. This I attribute to the absence of sufficient food. In the Cambridge marshes they remain until all the seeds have been consumed, and only reappear when the new crop is edible.

This Blackbird is a general feeder, eating insects, apparently in preference, and wild seed. They derive their name of Cow Blackbird from their keeping about that animal, and finding, either from her parasitic insects or her droppings, opportunities for food. They feed on the ground, and occasionally scratch for insects. At the South, to a limited extent, they frequent the rice-fields in company with the Redwinged Blackbird.

Mr. Nuttall states that if a Cow Blackbird’s egg is deposited in a nest alone it is uniformly forsaken, and he also enumerates the Summer Yellowbird as one of the nurses of the Cowbird. In both respects I think he is mistaken. So far from forsaking her nest when one of these eggs is deposited, the Red-eyed Vireo has been known to commence incubation without having laid any of her own eggs, and also to forsake her nest when the intrusive egg has been taken and her own left. The D. æstiva, I think, invariably covers up and destroys the Cowbird’s eggs when deposited before her own, and even when deposited afterwards.

The Cow Blackbird has no attractions as a singer, and has nothing that deserves the name of song. His utterances are harsh and unmelodious.

In September they begin to collect in large flocks, in localities favorable for their sustenance. The Fresh Pond marshes in Cambridge were once one of their chosen places of resort, in which they seemed to collect late in September, as if coming from great distances. There they remained until late in October, when they passed southward.

Mr. Ridgway only met with this species in two places, the valley of the Humboldt in September, and in June in the Truckee Valley. Their eggs were also obtained in the Wahsatch Mountains, deposited in the nest of Passerella schistacea, and in Bear River Valley in the nest of Geothlypis trichas.

Mr. Boardman informs me that the Cow Blackbird is a very rare bird in the neighborhood of Calais, Me., so much so that he does not see one of these birds once in five years, even as a bird of passage.

The eggs of this species are of a rounded oval, though some are more oblong than others, and are nearly equally rounded at either end. They vary from .85 of an inch to an inch in length, and from .65 to .70 in breadth. Their ground-color is white. In some it is so thickly covered with fine dottings of ashy and purplish-brown that the ground is not distinguishable. In others the egg is blotched with bold dashes of purple and wine-colored brown.

On the Rio Grande the eggs of the smaller southern race were found in the nests of Vireo belli, and in each of the nests of the Vireo pusillus found near Camp Grant, Arizona, there was an egg of this species. At Cape St. Lucas, Mr. Xantus found their eggs in nests of the Polioptila melanura. We have no information in regard to their habits, and can only infer that they must be substantially the same as those of the northern birds.

The eggs of the var. obscurus exhibit a very marked variation in size from those of the var. pecoris, and have a different appearance, though their colors are nearly identical. Their ground-color is white, and their markings a claret-brown. These markings are fewer, smaller, and less generally distributed, and the ground-color is much more apparent. They measure .60 by .55 of an inch, and their capacity as compared with the eggs of the pecoris is as 33 to 70,—a variation that is constant, and apparently too large to be accounted for on climatic differences.

Genus AGELAIUS, VieillAgelaius, Vieillot, “Analyse, 1816.” (Type, Oriolus phœniceus, L.)

Agelaius phœniceus.

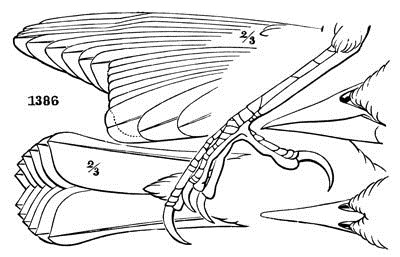

1386

Gen. Char. First quill shorter than second; claws short; the outer lateral scarcely reaching the base of the middle. Culmen depressed at base, parting the frontal feathers; length equal to that of the head, shorter than tarsus. Both mandibles of equal thickness and acute at tip, the edges much curved, the culmen, gonys, and commissure nearly straight or slightly sinuated; the length of bill about twice its height. Tail moderate, rounded, or very slightly graduated. Wings pointed, reaching to end of lower tail-coverts. Colors black with red shoulders in North American species. One West Indian with orange-buff. Females streaked except in two West Indian species.

Agelaius phœniceus.

The nostrils are small, oblong, overhung by a membranous scale. The bill is higher than broad at the base. There is no division between the anterior tarsal scutellæ and the single plate on the outside of the tarsus.

The females of two West Indian species are uniform black. Of these the male of one, A. assimilis of Cuba, is undistinguishable from that of A. phœniceus; and in fact we may without impropriety consider the former as a melanite race of the latter, the change appreciable only in the female. The A. humeralis, also of Cuba, is smaller, and black, with the lesser coverts brownish orange-buff.

Species and VarietiesCommon Characters. Males glossy black without distinct bluish lustre, lesser wing-coverts bright red. Females without any red, and either wholly black or variegated with light streaks, most conspicuous below.

A. phœniceus. Tail rounded. Red of shoulders a bright scarlet tint. Black of plumage without bluish lustre. Females with wing-coverts edged with brownish, or without any light edgings at all.

a. Female continuous deep black, unvariegated.

Middle wing-coverts wholly buff in maleWing, 4.40; tail, 3.80; culmen, .95; tarsus, 1.00. Hab. Cuba.

b. Females striped beneath … var. assimilis.30

Wing, 4.90; tail, 3.85; culmen, .96; tarsus, 1.10. Female. White stripes on lower parts exceeding the dusky ones in width; a conspicuous lighter superciliary stripe, and one strongly indicated on middle of the crown. Hab. Whole of North America, south to Guatemala … var. phœniceus.

Middle wing-coverts black, except at baseWing, 5.00; tail, 3.90; culmen, .90; tarsus, 1.10. Female. White stripes on lower parts narrower than dusky ones; the posterior portion beneath being almost continuously dusky. No trace of median stripe on crown, and the superciliary one indistinct. Hab. Pacific Province of United States, south through Western Mexico … var. gubernator.

Middle wing-coverts wholly white in maleB. tricolor. Tail square. Red of the shoulders a brownish-scarlet, or burnt-carmine tint. Black of the plumage (both sexes at all ages) with a silky bluish lustre. Female with wing-coverts edged with pure white.

Wing, 4.90; tail, 3.70; culmen, .97; tarsus, 1.13. Female. Like that of gubernator, but with scarcely any brownish tinge to the plumage, and the lesser wing-coverts sharply bordered with pure white. Hab. California (only ?).

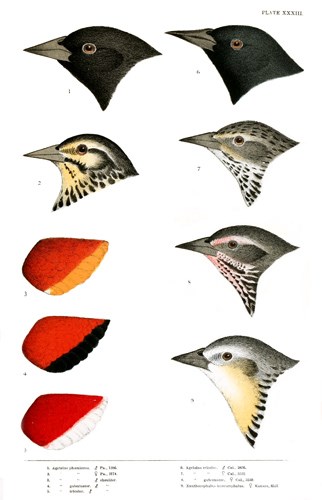

PLATE XXXIII.

1. Agelaius phœniceus. ♂ Pa., 1386.

2. Agelaius phœniceus. ♀ Pa., 2174.

3. Agelaius phœniceus. ♂ shoulder.

4. Agelaius gubernator. ♂ shoulder.

5. Agelaius tricolor. ♂ shoulder.

6. Agelaius tricolor. ♂ Cal., 2836.