полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Along the coast of Oregon and Washington Territory is a very peculiar race, represented in the collection by several specimens. These differ essentially in having the dark streaks above very sharply defined, broad and clear blackish-brown,28 while the lower parts are strongly tinged with yellow, even as deeply so as the throat. Additional specimens from the northwest coast may establish the existence of a race as distinct as any of those named above.

Var. alpestrisAlauda alpestris, Linn. S. N. I, 289.—Forst. Phil. Trans. LXII, 1772, 383.—Wilson,—Aud.—Jard.—Maynard, B. E. Mass. 1870, 121. Otocorys a. Finsch, Abh. Nat. 1870, 341 (synonomy and remarks). Alauda cornuta, Wils. Am. Orn. I, 1808, 85.—Rich. F. B. A. II. Eremophila c. Boie, Isis, 1828, 322.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 403.—Lord, P. R. A. Inst. IV, 118 (British Col.).—Cooper & Suckley, XII, 195.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. Ac. I, 1869, 218 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 251.—Samuels, 280. Phileremos c. Bonap. List, 1838. Otocoris c. Auct. Otocoris occidentalis, McCall, Pr. A. N. Sc. V, June, 1851, 218 (Santa Fé).—Baird, Stansbury’s Rep., 1852, 318.

Char. Adult. Frontal whitish crescent more than half as broad as the black patch behind it. Throat and forehead either tinged, more or less strongly, with yellow, or perfectly white. Pinkish tint above, a soft ashy-vinaceous.

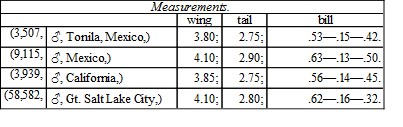

Measurements. (56,583 ♂, North Europe,) wing, 4.40; tail, 2.90; culmen, .60; width of white frontal crescent, .25; of black, .30. (3,780 ♂, Wisconsin,) wing, 4.20; tail, 3.00; culmen, .60; width of white frontal crescent, .30; of black, .26. (16,768 ♂, Hudson’s Bay Ter.,) wing, 4.55; tail, 3.10; culmen, .65; width of white frontal crescent, .35; of black, .36. (8,491 ♂, Fort Massachusetts,) wing, 4.35; tail, 3.15; culmen, .61; width of white frontal crescent, .27; of black, 27. (The three perfectly identical in colors.)

Young. On the upper parts the blackish greatly in excess of the whitish markings. Spots across jugulum distinct.

Hab. Northern Hemisphere; in North America, breeding in the Arctic regions and the open plains of the interior regions, from Illinois, Wisconsin, etc., to the Pacific, north of about 38°.

Var. chrysolæmaAlauda chrysolæma, Wagl. Isis, 1831, 350.—Bonap. P. Z. S. 1837, 111. Otocorys ch. Finsch, Abh. Nat. 1870, 341. Alauda minor, Giraud, 16 Sp. Tex. B. 1841. Alauda rufa, Aud. Birds Am. VII, 1843, 353, pl. ccccxcvii. Otocoris r., Heerm. X. s, 45. ? Otocorys peregrina, Scl. P. Z. S. 1855, 110, pl. cii. Eremophila p., Scl. Cat. Am. B. 1860, 127.

Char. Adult. Frontal crescent less than half as wide as the black. Throat and forehead deep straw-yellow; pinkish tints above deep cinnamon.

a. Specimens from California and Mexico, streaks on back, etc., very obsolete; darker central stripe to middle tail-feathers scarcely observable; white beneath.

b. Specimens from coast of Oregon and Washington Territory. Streaks on back, etc., very conspicuous; dark central stripe of tail-feathers distinct; yellow beneath.

Measurements. (8,734 ♂, Fort Steilacoom,) wing, 3.75; tail, 2.60; bill, .61—.15—.40.

Hab. Middle America, from the desert regions of the southern Middle Province of North America, south to Bogota.

Habits. Assuming the Shore Lark of the Labrador coast and the rufous Lark of the Western prairies to be one and the same species, but slightly modified by differences of locality, climate, or food, we have for this species, at all times, a wide range, and, during the breeding-season, a very unusual peculiarity,—their abundant distribution through two widely distant and essentially different regions.

During a large portion of the year, or from October to April, these birds may be found in all parts of the United States. Dr. Woodhouse found them very common throughout Texas, the Indian Territory, New Mexico, and California. Mr. Dresser states that he found the western variety—which he thinks essentially different in several respects from the eastern—in great numbers, from October to the end of March, in the prairies around San Antonio. Afterwards, at Galveston, in May and June, 1864, he noticed and shot several specimens. Although he did not succeed in finding any nests, he was very sure that they were breeding there. It is common, during winter, on the Atlantic coast, from Massachusetts to South Carolina. In Maine it is comparatively rare. In Arizona, Dr. Coues speaks of the western form as a permanent resident in all situations adapted to its wants. The same writer, who also had an opportunity of observing the eastern variety in Labrador, where he found it very abundant on all the moss-covered islands around the coast, could notice nothing in their voice, flight, or general manners, different from their usual habits in their southern migrations, except that during the breeding-season they do not associate in flocks.

Richardson states that this Lark arrives in the fur countries in company with the Lapland Bunting, with which it associates, and, being a shyer bird, would act as sentinel and give the alarm on the approach of danger. As Mr. Dall only obtained a single skin on the Yukon, it probably is not common there. Dr. Suckley states it to be a very abundant summer resident on the gravelly prairies near Fort Steilacoom, in Washington Territory. He describes it as a tame, unsuspicious bird, allowing a man to approach within a few feet of it. It is essentially a ground bird, rarely alighting on bushes or shrubs.

Dr. Cooper adds to this that the Shore Lark is common in the interior, but he only noticed one on the coast border. In ordinary seasons they seem to be permanent residents, and in winter to be both more gregarious and more common. He met with one as late as July 1, on a gravelly plain near Olympia, scratching out a hollow for its nest under a tussock of grass.

Dr. Cooper also found these birds around Fort Mohave in considerable flocks about the end of February, but all had left the valley by the end of March. About May 29 he found numbers of them towards the summits of the Providence range of mountains, west of the valley, and not far from four thousand feet above it, where they probably had nests. They were also common in July on the cooler plains towards the ocean, so that they doubtless breed in many of the southern portions of California, as well as at Puget Sound and on the Great Plains. Dr. Cooper states that in May or June the males rise almost perpendicularly into the air, until almost out of sight, and fly around in an irregular circle, singing a sweet and varied song for several minutes, when they descend nearly to the spot from which they started. Their nests were usually found in a small depression of the ground, often under a tuft of grass or a bush. Mr. Nuttall started a Shore Lark from her nest, on the plains, near the banks of the Platte. It was in a small depression on the ground, and was made of bent grass, and lined with coarse bison-hair. The eggs were olive-white, minutely spotted all over with a darker tinge.

According to Audubon, these Larks breed abundantly on the high and desolate granite tracts that abound along the coast of Labrador. These rocks are covered with large patches of mosses and lichens. In the midst of these this bird places her nest, disposed with so much care, and the moss so much resembling the bird in hue, that the nests are not readily noticed. When flushed from her nest, she flutters away, feigning lameness so cunningly as to deceive almost any one not on his guard. The male at once joins her, and both utter the most soft and plaintive notes of woe. The nest is embedded in the moss to its edges, and is composed of fine grasses, circularly disposed and forming a bed about two inches thick. It is lined with the feathers of the grouse and of other birds. The eggs, deposited early in July, are four or five in number, and are described by Mr. Audubon as marked with bluish as well as brown spots.

About a week before they can fly, the young leave the nest, and follow their parents over these beds of mosses to be fed. They run nimbly, and squat closely at the first approach of danger. If observed and pursued, they open their wings and flutter off with great celerity.

These birds reach Labrador early in June, when the male birds are very pugnacious, and engage frequently in very singular fights, in which often several others besides the first parties join, fluttering, biting, and tumbling over in the manner of the European House Sparrow. The male is described as singing sweetly while on the wing, but its song is comparatively short. It will also sing while on the ground, but less frequently, and with less fulness. Its call-note is quite mellow, and is at times so altered, in a ventriloquial manner, as to seem like that of another bird. As soon as the young are hatched their song ceases. It is said to feed on grass-seeds, the blossoms of small plants, and insects, often catching the latter on the wing, and following them to a considerable distance. It also gathers minute crustaceans on the sea-shore.

Mr. Ridgway found this species abundant over the arid wastes of the interior, and, in many localities, it was almost the only bird to be found. In its habits he could observe no differences between this bird and the alpestris. He met with their nests and eggs in the Truckee Reservation, June 3. The nest was embedded in the hard, grassy ground, beneath a small scraggy sage-bush, on the mesa, between the river and the mountains.

Mr. J. K. Lord mentions that, having encamped at Cedar Springs on the Great Plains of the Columbia, where the small stream was the only water within a long distance, he became interested in watching the movements of these Larks. As evening approached they came boldly in among the mules and men, intense thirst overcoming all sense of fear. He found these handsome little birds very plentiful throughout British Columbia. They were nesting very early on those sandy plains, even before the snow had left the ground. He saw young fledglings early in May.

A single specimen of this species was taken at Godhaab, Greenland, in October, 1835.

Eggs from Labrador are much larger in size than those from Wisconsin. Two eggs from the first, one obtained by Mr. Thienemann, the other by Mr. George Peck, of Burlington, Vt., measure .93 and .94 of an inch in length by .71 in breadth; while some from the West are only .83 in length and .63 in breadth, their greatest length being .90, and their largest breadth .69 of an inch. In their ground-color and markings, eggs from both localities vary about alike. The ground-color varies from a purplish-white to a dark gray, while the spots are in some a brownish-lavender, in others a brown, and, quite frequently, an olive-brown. In some they are in larger, scattered blotches; while in others they are in very fine minute dots so thickly and so uniformly diffused as almost to conceal the ground.

Family ICTERIDÆ.—The Orioles

Char. Primaries nine. Tarsi scutellate anteriorly; plated behind. Bill long, generally equal to the head or longer, straight or gently curved, conical, without any notch, the commissure bending downwards at an obtuse angle at the base. Gonys generally more than half the culmen, no bristles about the base of bill. Basal joint of the middle toe free on the inner side; united half-way on the outer. Tail rather long, rounded. Legs stout.

This family is strictly confined to the New World, and is closely related in many of its members to the Fringillidæ. Both have the angulated commissure and the nine primaries; the bill is, however, usually much longer; the rictus is completely without bristles, and the tip of the bill without notch.

The affinities of some of the genera are still closer to the family of Sturnidæ or Starlings, of which the Sturnus vulgaris may be taken as the type. The latter family, is, however, exclusively Old World, except for the occurrence of a species in Greenland, and readily distinguished by the constant presence of a rudimentary outer primary, making ten in all.

There are three subfamilies of the Icteridæ,—the Agelainæ, the Icterinæ, and the Quiscalinæ,29 which may be diagnosed as follows, although it is difficult to define them with precision:—

Agelainæ. Bill shorter than, or about equal to, the head; thick, conical, both mandibles about equal in depth; the outlines all more or less straight, the bill not decurved at tip. Tail rather short, nearly even or slightly rounded. Legs longer than the head, adapted for walking; claws moderately curved.

Icterinæ. Bill rather slender, about as long as the head; either straight or decurved. Lower mandible less thick than the upper; the commissure not sinuated. Tarsi not longer than the head, nor than middle toe; legs adapted for perching. Claws much curved.

Quiscalinæ. Tail lengthened, considerably or excessively graduated. Bill as long as,or longer than, the head; the culmen curved towards the end, the tip bent down, the cutting edges inflexed, the commissure sinuated. Legs longer than the head, fitted for walking.

Subfamily AGELAINÆ

Char. Bill stout, conical, and acutely pointed, not longer than the head; the outlines nearly straight, the tip not decurved. Legs adapted for walking, longer than the head. Claws not much curved. Tail moderate, shorter than the wings; nearly even.

The Agelainæ, through Molothrus and Dolichonyx, present a close relation to the Fringillidæ in the comparative shortness and conical shape of the bill, and, in fact, it is very difficult to express in brief words the distinctions which evidently exist. Dolichonyx may be set aside as readily determinate by the character of the feet and tail. The peculiar subfamily characteristics of Molothrus will be found under the generic remarks respecting it.

The following diagnosis will serve to define the genera:—

A. Bill shorter than the head. Feathers of head and nostrils as in B.

Dolichonyx. Tail-feathers with rigid stiffened acuminate points. Middle toe very long, exceeding the head.

Molothrus. Tail with the feathers simple; middle toe shorter than the tarsus or head.

B. Bill as long as the head. Feathers of crown soft. Nostrils covered by a scale which is directed more or less downwards.

Agelaius. First quill shorter than the second and third. Outer lateral claws scarcely reaching to the base of middle; claws moderate.

Xanthocephalus. First quill longest. Outer lateral claw reaching nearly to the tip of the middle. Toes and claws all much elongated.

C. Bill as long as, or longer than, the head. Feathers of crown with the shafts prolonged into stiffened bristles. Nostrils covered by a scale which stands out more or less horizontally.

Sturnella. Tail-feathers acute. Middle toe equal to the tarsus.

Trupialis. Tail-feathers rounded. Middle toe shorter than the tarsus.

Genus DOLICHONYX, SwainsonDolichonyx, Swainson, Zoöl. Journ. III, 1827, 351. (Type, Emberiza oryzivora, L.)

Dolichonyx oryzivorus.

977

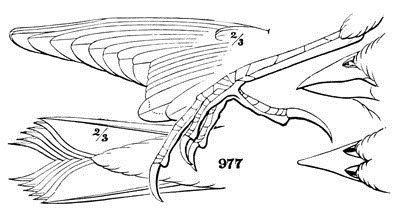

Gen. Char. Bill short, stout, conical, little more than half the head; the commissure slightly sinuated; the culmen nearly straight. Middle toe considerably longer than the tarsus (which is about as long as the head); the inner lateral toe longest, but not reaching the base of the middle claw. Wings long, first quill longest. Tail-feathers acuminately pointed at the tip, with the shaft stiffened and rigid, as in the Woodpeckers.

The peculiar characteristic of this genus is found in the rigid scansorial tail and the very long middle toe, by means of which it is enabled to grasp the vertical stems of reeds or other slender plants. The color of the single species is black, varied with whitish patches on the upper parts.

Dolichonyx oryzivorus, SwainsonBOBOLINK; REEDBIRD; RICEBIRDEmberiza oryzivora, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 311.—Gm. I, 1788, 850.—Wilson, Am. Orn. II, 1810, 48, pl. xii, f. 1, 2. Passerina oryzivora, Vieillot, Nouv. Dict. XXV, 1817, 3. Dolichonyx oryzivora, Swainson, Zoöl. Jour. III, 1827, 351.—Ib. F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 278.—Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850, 437.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 139.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 10, pl. ccxi.—Gosse, Birds Jam. 1847, 229.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 522.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 1858, 266.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 255.—Samuels, 335. Icterus agripennis, Bonap. Obs. Wils. 1824, No. 87. Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1831, 283; V, 1839, 486, pl. liv.—Nutt. Man. I, 1832, 185. Icterus (Emberizoides) agripennis, Bon. Syn. 1828, 53. Dolichonyx agripennis, Rich. List, 1837. Psarocolius caudacutus, Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, 32.

Dolichonyx oryzivorus.

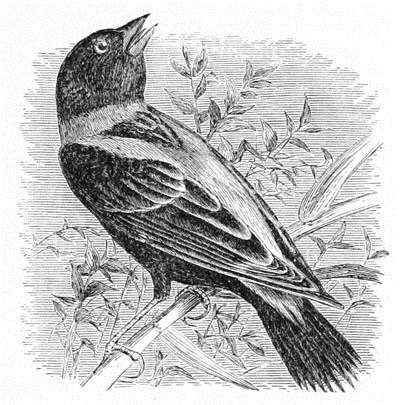

Sp. Char. General color of male in spring, black; the nape brownish cream-color; a patch on the side of the breast, the scapulars, and rump, white, shading into light ash on the upper tail-coverts and the back below the interscapular region. The outer primaries sharply margined with yellowish-white; the tertials less abruptly; the tail-feathers margined at the tips with pale brownish-ash. In autumn totally different, resembling the female.

Female, yellowish beneath; two stripes on the top of the head, and the upper parts throughout, except the back of the neck and rump, and including all the wing-feathers generally, dark brown, all edged with brownish-yellow, which becomes whiter near the tips of the quills. The sides sparsely streaked with dark brown, and a similar stripe behind the eye. There is a superciliary and a median band of yellow on the head. Length of male, 7.70; wing, 3.83; tail, 3.15.

Hab. Eastern United States to the high Central Plains. North to Selkirk Settlement, and Ottawa, Canada; and west to Salt Lake Valley, Utah, and Ruby Valley, Nevada (Ridgway); Cuba, winter (Caban.); Bahamas (Bryant); Jamaica (Gosse, Scl., Oct.; March, Oct., and in spring); James Island, Galapagos, Oct. (Gould); Sombrero, W. I. (Lawrence); Brazil (Pelzeln); Yucatan.

A female bird from Paraguay (Dec., 1859) is undistinguishable from the average of northern ones, except by the smaller size. Specimens from the western plains differ from those taken near the Atlantic Coast in having the light areas above paler, and less obscured by the grayish wash so prevalent in the latter; the ochraceous of the nape being very pale, and at the same time pure.

Habits. The well-known and familiar Bobolink of North America has, at different seasons of the year, a remarkably extended distribution. In its migrations it traverses all of the United States east of the high central plains to the Atlantic as far to the north as the 54th parallel, which is believed to be its most northern limit, and which it reaches in June. In the winter it reaches, in its wandering, the West Indies, Central America, the northern and even the central portions of South America. Von Pelzeln obtained Brazilian specimens from Matogrosso and Rio Madeira in November, and from Marabitanas, April 4th and 13th. Those procured in April were in their summer or breeding plumage, suggesting the possibility of their breeding in the high grounds of South America. Sclater received specimens from Santa Marta and from Bolivia. Other specimens have been reported as coming from Rio Negro, Rio Napo, in Brazil, Cuba, Jamaica, Porto Rico, Paraguay, Buenos Ayres, etc.

In North America it breeds from the 42d to the 54th parallel, and in some parts of the country it is very abundant at this season. The most southern breeding locality hitherto recorded is the forks of the Susquehanna River, along the west branch of which, especially in the Wyoming Valley, it was formerly very abundant.

Mr. Ridgway also observed this bird in Ruby Valley where, among the wheat-fields, small companies were occasionally seen in August. He was informed that, near Salt Lake City, these birds are seen in May, and again late in the summer, when the grain is ripe.

Of all our unimitative and natural songsters the Bobolink is by far the most popular and attractive. Always original and peculiarly natural, its song is exquisitely musical. In the variety of its notes, in the rapidity with which they are uttered, and in the touching pathos, beauty, and melody of their tone and expression, its notes are not equalled by those of any other North American bird. We know of none, among our native feathered songsters, whose song resembles, or can be compared with it.

In the earliest approaches of spring, in Louisiana, when small flocks of male Bobolinks make their first appearance, they are said, by Mr. Audubon, to sing in concert; and their song thus given is at once exceedingly novel, interesting, and striking. Uttered with a volubility that even borders upon the burlesque and the ludicrous, the whole effect is greatly heightened by the singular and striking manner in which first one singer and then another, one following the other until all have joined their voices, take up the note and strike in, after the leader has set the example and given the signal. In this manner sometimes a party of thirty or forty Bobolinks will begin, one after the other, until the whole unite in producing an extraordinary medley, to which no pen can do justice, but which is described as very pleasant to listen to. All at once the music ceases with a suddenness not less striking and extraordinary. These concerts are repeated from time to time, usually as often as the flock alight. This performance may also be witnessed early in April, in the vicinity of Washington, the Smithsonian grounds being a favorite place of resort.

By the time these birds have reached, in their spring migrations, the 40th parallel of latitude, they no longer move in large flocks, but have begun to separate into small parties, and finally into pairs. In New England the Bobolink treats us to no such concerts as those described by Audubon, where many voices join in creating their peculiar jingling melody. When they first appear, usually after the middle of May, they are in small parties, composed of either sex, absorbed in their courtships and overflowing with song. When two or three male Bobolinks, decked out in their gayest spring apparel, are paying their attentions to the same drab-colored female, contrasting so strikingly in her sober brown dress, their performances are quite entertaining, each male endeavoring to outsing the other. The female appears coy and retiring, keeping closely to the ground, but always attended by the several aspirants for her affection. After a contest, often quite exciting, the rivalries are adjusted, the rejected suitors are driven off by their more fortunate competitor, and the happy pair begin to put in order a new home. It is in these love-quarrels that their song appears to the greatest advantage. They pour out incessantly their strains of quaint but charming music, now on the ground, now on the wing, now on the top of a fence, a low bush, or the swaying stalk of a plant that bends with their weight. The great length of their song, the immense number of short and variable notes of which it is composed, the volubility and confused rapidity with which they are poured forth, the eccentric breaks, in the midst of which we detect the words “bob-o-link” so distinctly enunciated, unite to form a general result to which we can find no parallel in any of the musical performances of our other song-birds. It is at once a unique and a charming production. Nuttall speaks of their song as monotonous, which is neither true nor consistent with his own description of it. To other ears they seem ever wonderfully full of variety, pathos, and beauty.