полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Icterus icterocephalus, Bonap. Am. Orn. I, 1825, 27, pl. iii.—Nutt. Man. I, 1832, 176.—Ib., (2d ed.,) 187 (not Oriolus icterocephalus, Linn.). Agelaius icterocephalus, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 188. Icterus (Xanthornus) xanthocephalus, Bonap. J. A. N. Sc. V, II, Feb. 1826, 222.—Ib. Syn. 1828, 52. Icterus xanthocephalus, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 6, pl. ccclxxxviii. Agelaius xanthocephalus, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 281.—Bon. List, 1838.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 140.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 24, pl. ccxiii.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. and Or. Route; Rep. P. R. R. Surv. VI, IV, 1857, 86.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 1858, 361.—Heerm. X, S, 52 (nest). Agelaius longipes, Swainson, Phil. Mag. I, 1827, 436. Psarocolius perspicillatus, “Licht.” Wagler, Isis, 1829. VII, 753. Icterus perspicillatus, “Licht. in Mus.” Wagler, as above. Xanthocephalus perspicillatus, Bonap. Consp. 1850, 431. Icterus frenatus, Licht. Isis, 1843, 59.—Reinhardt, in Kroyer’s Tidskrift, IV.—Ib. Vidensk. Meddel. for 1853, 1854, 82 (Greenland). Xanthocephalus icterocephalus, Baird, M. B. II, Birds, 18; Birds N. Am. 1858, 531.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 267.

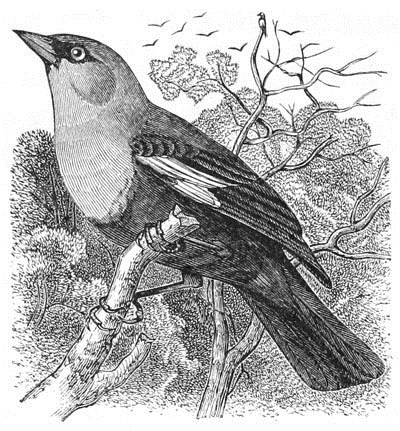

Sp. Char. First quill nearly as long as the second and third (longest), decidedly longer than the fourth. Tail rounded, or slightly graduated. General color black, including the inner surface of wings and axillaries, base of lower mandible all round, feathers adjacent to nostrils, lores, upper eyelids, and remaining space around the eye. The head and neck all round; the forepart of the breast, extending some distance down on the median line, and a somewhat hidden space round the anus, yellow. A conspicuous white patch at the base of the wing formed by the spurious feathers, interrupted by the black alula.

Xanthocephalus icterocephalus.

Female smaller, browner; the yellow confined to the under parts and sides of the head, and a superciliary line. A dusky maxillary line. No white on the wing. Length of male, 10 inches; wing, 5.60; tail, 4.50.

Hab. Western America from Texas, Illinois, Wisconsin, and North Red River, to California, south into Mexico; Greenland (Reinhardt); Cuba (Cabanis, J. VII, 1859, 350); Massachusetts (Maynard, D. C. Mass. 1870, 122); Volusia, Florida (Mus. S. I.); Cape St. Lucas.

The color of the yellow in this species varies considerably; sometimes being almost of a lemon-yellow, sometimes of a rich orange. There is an occasional trace of yellow around the base of the tarsus. Immature males show every gradation between the colors of the adult male and female.

A very young bird (4,332, Dane Co., Wis.) is dusky above, with feathers of the dorsal region broadly tipped with ochraceous, lesser and middle wing-coverts white tinged with fulvous, dusky below the surface, greater coverts very broadly tipped with fulvous-white; primary coverts narrowly tipped with the same. Whole lower parts unvariegated fulvous-white; head all round plain ochraceous, deepest above.

Habits. The Yellow-headed Blackbird is essentially a prairie bird, and is found in all favorable localities from Texas on the south to Illinois and Wisconsin, and thence to the Pacific. A single specimen is recorded as having been taken in Greenland. This was September 2, 1820, at Nenortalik. Recently the Smithsonian Museum has received a specimen from New Smyrna, in Florida. In October, 1869, a specimen of this bird was taken in Watertown, Mass., and Mr. Cassin mentions the capture of several near Philadelphia. These erratic appearances in places so remote from their centres of reproduction, and from their route in emigration, sufficiently attest the nomadic character of this species.

They are found in abundance in all the grassy meadows or rushy marshes of Illinois and Wisconsin, where they breed in large communities. In swamps overgrown with tall rushes, and partially overflowed, they construct their nests just above the water, and build them around the stems of these water-plants, where they are thickest, in such a manner that it is difficult to discover them, except by diligent search, aided by familiarity with their habits.

In Texas Mr. Dresser met with a few in the fall, and again in April he found the prairies covered with these birds. For about a week vast flocks remained about the town, after which they suddenly disappeared, and no more were seen.

In California, Dr. Cooper states that they winter in large numbers in the middle districts, some wandering to the Colorado Valley and to San Diego. They nest around Santa Barbara, and thence northward, and are very abundant about Klamath Lake. They associate with the other Blackbirds, but always keep in separate companies. They are very gregarious, even in summer.

Dr. Cooper states that the only song the male attempts consists of a few hoarse, chuckling notes and comical squeakings, uttered as if it was a great effort to make any sound at all.

Dr. Coues speaks of it as less numerous in Arizona than at most other localities where found at all. He speaks of it as a summer resident, but in this I think he may have been mistaken.

In Western Iowa Mr. Allen saw a few, during the first week in July, about the grassy ponds near Boonesboro’. He was told that they breed in great numbers, north and east of that section, in the meadows of the Skunk River country. He also reports them as breeding in large numbers in the Calumet marshes of Northern Illinois.

Sir John Richardson found these birds very numerous in the interior of the fur countries, ranging in summer as far to the north as the 58th parallel, but not found to the eastward of Lake Winnipeg. They reached the Saskatchewan by the 20th of May, in greater numbers than the Redwings.

Through California, as well as in the interior, Mr. Ridgway found the Yellow-headed Blackbird a very abundant species, even exceeding in numbers the A. phœniceus, occurring in the marshes filled with rushes. This species he found more gregarious than the Redwing, and frequently their nests almost filled the rushes of their breeding-places. Its notes he describes as harsher than those of any other bird he is acquainted with. Yet they are by no means disagreeable, while frequently their attempts at a song were really amusing. Their usual note is a deep cluck, similar to that of most Blackbirds, but of a rather deeper tone. In its movements upon the ground its gait is firm and graceful, and it may frequently be seen walking about over the grassy flats, in small companies, in a manner similar to the Cow Blackbird, which, in its movements, it greatly resembles. It nests in the sloughs, among the tulé, and the maximum number of its eggs is four.

Mr. W. J. McLaughlin of Centralia, Kansas, writes (American Naturalist, III, p. 493) that these birds arrive in that region about the first of May, and all disappear about the 10th of June. He does not think that any breed there. During their stay they make themselves very valuable to the farmers by destroying the swarms of young grasshoppers. On the writer’s land the grasshoppers had deposited their eggs by the million. As they began to hatch, the Yellow-heads found them out, and a flock of about two hundred attended about two acres each day, roving over the entire lot as wild pigeons feed, the rear ones flying to the front as the insects were devoured.

Mr. Clark met with these birds at New Leon, Mexico. They were always in flocks, mingled with two or three of its congeneric species. They were found more abundant near the coast than in the interior. There was a roost of these birds on an island in a lagoon near Fort Brown. Between sunset and dark these birds could be seen coming from all quarters. For about an hour they kept up a constant chattering and changing of place. Another similar roost was on an island near the mouth of the Rio Grande.

Dr. Kennerly found them very common near Janos and also near Santa Cruz, in Sonora. At the former place they were seen in the month of April in large flocks. He describes them as quite domestic in their habits, preferring the immediate vicinity of the houses, often feeding with the domestic fowls in the yards.

Dr. Heermann states that these birds collect in flocks of many thousands with the species of Agelaius, and on the approach of spring separate into smaller bands, resorting in May to large marshy districts in the valleys, where they incubate. Their nests he found attached to the upright stalks of the reeds, and woven around them, of flexible grasses, differing essentially from the nests of the Agelaii in the lightness of their material. The eggs, always four in number, he describes as having a ground of pale ashy-green, thickly covered with minute dots of a light umber-brown.

Mr. Nuttall states that on the 2d of May, during his western tour, he saw these birds in great abundance, associated with the Cowbird. They kept wholly on the ground, in companies, the sexes separated by themselves. They were digging into the earth with their bills in search of insects and larvæ. They were very active, straddling about with a quaint gait, and now and then whistling out, with great effort, a chuckling note, sounding like ko-kuk kie-ait. Their music was inferior even to the harsh notes of M. pecoris.

Several nests of this species, procured in the marshes on the banks of Lake Koskonong, in Southern Wisconsin, were sent me by Mr. Kumlien; they were all light, neat, and elegant structures, six inches in diameter and four in height. The cavity had a diameter of three and a depth of two and a half inches. The base, periphery, and the greater portion of these nests were made of interwoven grasses and sedges. The grasses were entire, with their panicles on. They were impacted together in masses. The inner portions of these nests were made of finer materials of the same. They were placed in the midst of large, overflowed marshes, and were attached to tall flags, usually in the midst of clumps of the latter, and these were so close in their growth that the nests were not easily discovered. They contained, usually, from five to six eggs. These are of an oblong-oval shape, and measure 1.02 inches in length by .70 of an inch in breadth. Their ground-color is of a pale greenish-white, profusely covered with blotches and finer dottings of drab, purplish-brown, and umber.

Genus STURNELLA, VieillotSturnella, Vieillot, Analyse, 1816. (Type, Alauda magna, L.)

Sturnella magna.

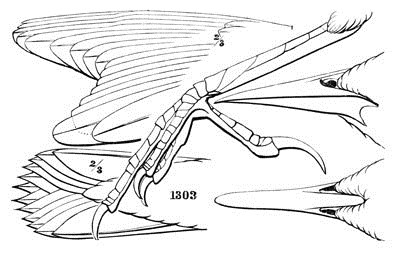

1303

Sturnella magna.

Gen. Char. Body thick, stout; legs large, toes reaching beyond the tail. Tail short, even, with narrow acuminate feathers. Bill slender, elongated; length about three times the height; commissure straight from the basal angle. Culmen flattened basally, extending backwards and parting the frontal feathers; longer than the head, but shorter than tarsus. Nostrils linear, covered by an incumbent membranous scale. Inner lateral toe longer than the outer, but not reaching to basal joint of middle; hind toe a little shorter than the middle, which is equal to the tarsus. Hind claw nearly twice as long as the middle. Feathers of head stiffened and bristly; the shafts of those above extended into a black seta. Tertials nearly equal to the primaries. Feathers above all transversely banded. Beneath yellow, with a black pectoral crescent.

The only species which we can admit is the S. magna, though under this name we group several geographical races. They may be distinguished as follows:—

Species and Varieties1. S. magna. Above brownish, or grayish, spotted and barred with black; crown divided by a median whitish stripe; side of the head whitish, with a blackish streak along upper edge of the auriculars. Beneath more or less yellowish, with a more or less distinct dusky crescent on the jugulum. Sides, flanks, and crissum whitish, streaked with dusky; lateral tail-feathers partly white. Adult. Supraloral spot, chin, throat, breast, and abdomen deep gamboge-yellow; pectoral crescent deep black. Young. The yellow only indicated; pectoral crescent obsolete. Length, about 9.00 to 10.50 inches. Sexes similar in color, but female much smaller.

A. In spring birds, the lateral stripes of the vertex either continuous black, or with black largely predominating; the black spots on the back extending to the tip of the feather, or, if not, the brown tip not barred (except in winter dress). Yellow of the throat confined between the maxillæ, or just barely encroaching upon their lower edge. White of sides, flanks, and crissum strongly tinged with ochraceous.

a. Pectoral crescent much more than half an inch wide.

Wing, 4.50 to 5.00; culmen, 1.20 to 1.50; tarsus, 1.35 to 1.55; middle toe, 1.10 to 1.26 (extremes of a series of four adult males). Lateral stripe of the crown continuously black; black predominating on back and rump (heavy stripes on ochraceous ground). Light brown serrations on tertials and tail-feathers reaching nearly to the shaft (sometimes the terminal ones uninterrupted, isolating the black bars). Hab. Eastern United States … var. magna.

Wing, 3.75 to 4.30; culmen, 1.15 to 1.30; tarsus, 1.50 to 1.75; middle toe, 1.10 to 1.25. (Ten adult males!) Colors similar, but with a greater predominance of black; black heavily prevailing on back and rump, and extending to tip of feathers; also predominates on tertials and tail-feathers. Hab. Mexico and Central America … var. mexicana.31

Wing, 4.45; culmen, 1.62; tarsus, 1.50; middle toe, 1.20. (One specimen). Colors exactly as in last. Hab. Brazil … var. meridionalis.32

b. Pectoral crescent much less than half an inch wide.

Wing, 3.90 to 4.10; culmen, 1.25 to 1.35; tarsus, 1.40 to 1.55; middle toe, 1.00 to 1.20. (Three adult males.) Colors generally similar to magna, but crown decidedly streaked, though black predominates; ground-color above less reddish than in either of the preceding, with markings as in magna. Pectoral crescent about .25 in breadth. Hab. Cuba … var. hippocrepis.33

B. In spring birds, crown about equally streaked with black and grayish; black spots of back occupying only basal half of feathers, the terminal portion being grayish-brown, with narrow bars of black; feathers of the rump with whole exposed portion thus barred. Yellow of the throat extending over the maxillæ nearly to the angle of the mouth.

Wing, 4.40 to 5.05; culmen, 1.18 to 1.40; tarsus, 1.30 to 1.45. (Six adult males.) A grayish-brown tint prevailing above; lesser wing-coverts concolor with the wings (instead of very decidedly more bluish); black bars of tertials and tail-feathers clean, narrow, and isolated. White of sides, flanks, and crissum nearly pure. Hab. Western United States and Western Mexico … var. neglecta.

In magna and neglecta, the feathers of the pectoral crescent are generally black to the base, their roots being grayish-white; one specimen of the former, however, from North Carolina, has the roots of the feathers yellow, forbidding the announcement of this as a distinguishing character; mexicana may have the bases of these feathers either yellow or grayish; while hippocrepis has only the tips of the feathers black, the whole concealed portion being bright yellow.

In mexicana, there is more of an approach to an orange tint in the yellow than is usually seen in magna, but specimens from Georgia have a tint not distinguishable; in both, however, as well as in hippocrepis, there is a deeper yellow than in neglecta, in which the tint is more citreous.

As regards the bars on tertials and tail, there is considerable variation. Sometimes in either of the species opposed to neglecta by this character there is a tendency to their isolation, seen in the last few toward the ends of the feathers; but never is there an approach to that regularity seen in neglecta, in which they are isolated uniformly everywhere they occur. Two specimens only (54,064 California and 10,316 Pembina) in the entire series of neglecta show a tendency to a blending of these bars on the tail.

Magna, mexicana, meridionalis and hippocrepis, are most similar in coloration; neglecta is most dissimilar compared with any of the others. Though each possesses peculiar characters, they are only of degree; for in the most widely different forms (neglecta and mexicana) there is not the slightest departure from the pattern of coloration; it is only a matter of extension or restriction of the several colors, or a certain one of them, that produces the differences.

Each modification of plumage is attended by a still greater one of proportions, as will be seen from the diagnoses; thus, though neglecta is the largest of the group, it has actually the smallest legs and feet; with nearly the same general proportions, magna exceeds it in the latter respects (especially in the bill), while mexicana, a very much smaller bird than either, has disproportionally and absolutely larger legs and feet united with the smallest size otherwise in the whole series. Meridionalis presents no differences from the last, except in proportions of bill and feet; for while the latter is the smallest of the series, next to neglecta, it has a bill much exceeding that of any other.

The markings of the upper plumage of the young or even winter birds are different in pattern from those of the adult; the tendency being toward the peculiar features of the adult neglecta; the various species in these stages being readily distinguishable, however, by the general characters assigned. Mexicana and neglecta are both in proportions and colors the most widely different in the whole series; hippocrepis and neglecta the most similar. The relation of the several races to each other is about as follows:—

A. Yellow of throat confined within maxillæ.

Crown with black streaks predominating.

Smallest species, with reddish tints, and maximum amount of black.

Largest bill … meridionalis.

Smallest bill; largest feet … mexicana.

Next largest species, with less reddish tints, and smaller amount of black. Bill and feet the standard of comparison … magna

Crown with the light streaks predominating.

Narrowest pectoral crescent … hippocrepis

B. Yellow of throat covering maxillæ.

Crown with black and light streaks about equal.

Largest species, with grayish tints, and minimum amount of black.

Smallest feet … neglecta.

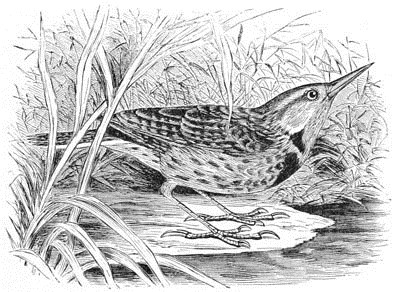

Sturnella magna, SwainsonMEADOW LARK; OLD FIELD LARKAlauda magna, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1758, 167, ed. 10 (based on Alauda magna, Catesby, tab. 33).—Ib., (12th ed.,) 1766, 289.—Gm. I, 1788, 801.—Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 20, pl. xix.—Doughty, Cab. I, 1830, 85, pl. V. Sturnella magna, Swainson, Phil. Mag. I, 1827, 436.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 535.—Samuels, 343. Sturnus ludovicianus, Linnæus, Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 290.—Gm. I, 802.—Lath. Ind. I, 1790, 323.—Bon. Obs. Wils. 1825, 130.—Licht. Verz. 1823, No. 165.—Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 1834, 216; V, 1839, 492, pl. cxxxvi. Sturnella ludoviciana, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 282.—Nuttall, Man. I, 1832, 147.—Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850, 429.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 148.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 70, pl. ccxxiii.—Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 192.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 288. Sturnella collaris, Vieill. Analyse, 1816.—Ib. Galerie des Ois. I, 1824, 134, pl. xc. Sturnus collaris, Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, 1.—Ib. Isis, 1831, 527. “Cacicus alaudarius, Daudin,” Cabanis.

Sp. Char. The feathers above dark brown, margined with brownish-white, and with a terminal blotch of pale reddish-brown. Exposed portions of wings and tail with dark brown bars, which on the middle tail-feathers are confluent along the shaft. Beneath yellow, with a black pectoral crescent, the yellow not extending on the side of the maxilla; sides, crissum, and tibiæ pale reddish-brown, streaked with blackish. A light median and superciliary stripe, the latter yellow anterior to the eye; a black line behind. Female smaller and duller. Young with pectoral crescent replaced by streaks; the yellow of under surface replaced more or less by ochraceous or pale fulvous. Length, 10.60; wing, 5.00; tail, 3.70; bill above, 1.35.

Hab. Eastern United States to the high Central Plains, north to Southern British Provinces. England (Sclater, Ibis, III, 176).

Habits. The eastern form of the Meadow Lark is found in all the eastern portions of the United States, from Florida to Texas at the south, and from Nova Scotia to the Missouri at the north. Richardson met with it on the Saskatchewan, where it arrives about the first of May. In a large portion of the United States it is resident, or only partially migratory.

In Maine this species is not abundant. A few are found in Southern Maine, even as far to the east as Calais, where it is very rare. It was not found in Oxford County by Mr. Verrill. In New Hampshire and Vermont, especially in the southern portions, it is much more abundant. Throughout Massachusetts it is a common summer visitant, a few remaining all winter, the greater number coming in March and leaving again in November, at which time they seem to be somewhat, though only partially, gregarious. South of Massachusetts it becomes more generally resident, and is only very partially migratory, where the depth of snow compels them to seek food elsewhere. Wilson states that he met a few of these birds in the month of February, during a deep snow, among the heights of the Alleghanies, near Somerset, Penn.

The favorite resorts of this species are old fields, pasture-lands, and meadows, localities in which they can best procure the insects, largely coleopterous, and the seeds on which they feed. They are not found in woods or thickets, or only in very exceptional cases.

In New England they are shy, retiring birds, and are rarely seen in the neighborhood of houses; but in Georgia and South Carolina, Wilson found them swarming among the rice plantations, and running about in the yards and the out-buildings, in company with the Killdeer Plovers, with little or no appearance of fear, and as if domesticated.

In Alabama and West Florida, Mr. Nuttall states, the birds abound during the winter months, and may be seen in considerable numbers in the salt marshes, seeking their food and the shelter of the sea-coast. They are then in loose flocks of from ten to thirty. At this season many are shot and brought to market. By some their flesh is said to be sweet and good; but this is denied by Audubon, who states it to be tough and of unpleasant flavor.

Mr. Sclater records the occurrence of one or more individuals of this species in England.

The song of the eastern Meadow Lark is chiefly distinguished for its sweetness more than any other excellence. When, in spring, at the height of their love-season, they alight on the post of a fence, a bush, or tree, or any other high object, they will give utterance to notes that, in sweetness and tenderness of expression, are surpassed by very few of our birds. But they are wanting in variety and power, and are frequently varied, but not improved, by the substitution of chattering call-notes, which are much inferior in quality. It is noticeable that at the West there is a very great improvement in the song of this bird as compared with that of their more eastern kindred, though still very far from equalling, either in volume, variety, or power, the remarkable song of the neglecta.

In the fall of the year these birds collect in small companies, and feed together in the same localities, but keeping, individually, somewhat apart.