полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

Sitta pygmæa (I, 120). This bird is probably a geographical form of S. pusilla, as suggested by Mr. Allen (Bull. Mus. Comp. Zoöl., Vol. III, No. 6, p. 115).

Sitta pusilla (I, 122). Young specimens collected at Aiken, S. C., by Mr. C. H. Merriam, are quite different in color from the adult plumage. The head is pale dull ashy, instead of light hair-brown, and the colors are duller generally. There is a near approach to S. pygmæa in their appearance.

Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus (I, 132). This species has been collected at Toquerville, Southern Utah, by Mr. Henshaw, and in Southern Nevada by Mr. Bischoff, naturalists to Lieutenant Wheeler’s expedition.

Salpinctes obsoletus (I, 135). The range of this species has been remarkably extended by the capture of a specimen in Decatur County, Southern Iowa, where others were seen, by Mr. T. M. Trippe. See Proc. Boston Soc. N. H., December, 1872, p. 236.

Catherpes mexicanus, var. conspersus (I, 139). Numerous specimens obtained in Colorado by Mr. Allen and Mr. Aiken, and in Southern Utah by Mr. Henshaw, establish the fact of great uniformity in the characters of this race, and its distinctness from var. mexicanus. On page 139 “it is noticed that it is a remarkable fact that this northern race should be so much smaller than the Mexican one, especially in view of the fact that it is a resident bird in even the most northern parts of its ascertained habitat.” As we find this peculiarity exactly paralleled in the Thryothorus ludovicianus of the Atlantic States (see below), may not these facts point out a law to the effect that in species which belong to essentially tropical families, with only outlying genera or species in the temperate zone, the increase in size with latitude is toward the region of the highest development of the group?

Dr. Cooper met with two specimens of this species in California in 1872; one about twelve miles back of San Diego, the other the same distance back of San Buenaventura, and both at the foot of lofty, rugged mountains. Their song he compares to loud ringing laughter; it is so shrill as to be heard at quite a distance, and seems as if it must be produced by a much larger bird.

Thryothorus ludovicianus (I, 142). Specimens of this species from Miami, Fla., are much darker colored than those from the Middle States (Maryland, Illinois, and southward), as might be expected; but very strangely, they are also much larger. In colors they very nearly resemble var. berlandieri, from the Lower Rio Grande.

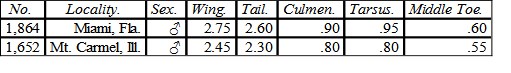

A specimen in Mr. Ridgway’s collection (No. 1,864, January 9), from Miami, Fla., compares with one from Southern Illinois (No. 1,652, Mt. Carmel, January, 1871) as follows:—

In coloration they are more nearly alike, the Florida specimen being hardly appreciably darker on the upper surface, though the lower parts are much deeper ochraceous, almost rufous. The Illinois specimen is deep ochraceous beneath, just about intermediate between Maryland and Florida specimens. Another Florida specimen (No. 62,733, Mus. S. I.; C. J. Maynard) measures: wing, 2.50; tail, 2.40; culmen, .85.

Thryothorus bewicki, var. leucogaster (I, 147). Specimens of this form were obtained at Toquerville, Southern Utah, in October, 1872, by Mr. Henshaw, attached to Lieutenant Wheeler’s expedition.

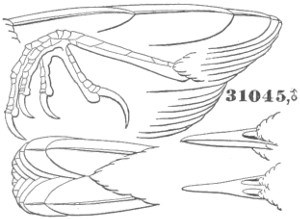

31045, ♂

Troglodytes parvulus, var. hyemalis.

Troglodytes parvulus, var. hyemalis (I, 155). Dr. Cooper has noticed a few of these Wrens near San Buenaventura in winter, after November 10. They probably reside in the summer in the high coast mountains lying east as well as in the Sierra Nevada. Outlines, omitted before, are here given.

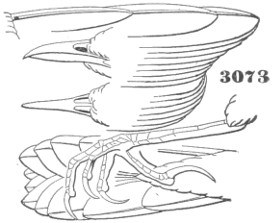

Cistothorus stellaris (I, 159). Mr. Henshaw obtained good evidence of this bird’s breeding at Utah Lake. Nests and eggs were found in a farm-house, unquestionably those of this species, and said to have been obtained among the tulés or sedges along the shore of the lake. Outlines of this species are here given.

3073

Cistothorus stellaris.

Anthus ludovicianus (I, 171). Mr. Allen found this species breeding in the summer of 1871 on the summit of Mt. Lincoln, Colorado Territory, above the timber-line, at an altitude of over 13,000 feet.

Helmitherus vermivorus (I, 187). Professor Frank H. Snow procured a specimen of this species near Lawrence, Kansas, May 6, 1873.

Helmitherus swainsoni (I, 190). Was obtained in Florida by Mr. W. Thaxter.

Helminthophaga virginiæ (I, 199). Very common in El Paso County, Colorado, where it was obtained by Mr. Aiken.

Helminthophaga luciæ (I, 200). We are indebted to Captain Bendire for the discovery of the nest and eggs of this comparatively new Warbler. He first met with its nest near Tucson, Arizona, May 19, 1872. Unlike all the rest of this genus, which, so far as is known, build their nests on the ground, this species was found nesting something after the manner of the common Gray Creeper, between the loose bark and the trunk of a dead tree, a few feet from the ground. Except in their smaller size the eggs also bear a great resemblance to those of the Creeper. In shape they are nearly spherical, their ground is of a crystal whiteness, spotted, chiefly around the larger end, with fine dottings of a purplish-red. They measure .54 of an inch in length by .45 in breadth.

Helminthophaga celata, var. lutescens (I, 204). See Am. Nat. Vol. VII, October, 1873, p. 606.

Helminthophaga peregrina (I, 205). Obtained in El Paso County, Colorado, in September, 1873, by Mr. Aiken.

Parula americana (I, 208). Obtained in May in El Paso County, Colorado, by Mr. Aiken.

Dendroica vieilloti, var. bryanti (I, 218). See Am. Nat. VII, October, 1873, p. 606.

Dendroica auduboni (I, 229). In July, 1870, Dr. Cooper found families of this species fully fledged, wandering through the woods, at the summit pass of the Central Pacific Railroad, 7,000 feet altitude, confirming his supposition that they breed in the high Sierra Nevada. There they are very numerous in summer, following the retreating snow to this elevation about May 1, when the males are in full plumage, retaining it till August. Their song is always faint, and similar to that of D. æstiva.

Dendroica cærulea (I, 235). A nest, containing one egg, of the Cærulean Warbler, was obtained in June, 1873, by Frank S. Booth, the son of James Booth, Esq., the well-known taxidermist of Drummondville, Ontario, near Niagara Falls. The nest was built in a large oak-tree at the height of fifty feet or more from the ground. It was placed horizontally on the upper surface of a slender limb, between two small twigs, and the branch on which it was thus saddled was only an inch and a half in thickness. Being nine feet from the trunk of the tree, it was secured with great difficulty. The nest is a rather slender fabric, somewhat similar to the nest of the Redstart, and quite small for the bird. It has a diameter of 2½ inches, and is 1¼ inches in depth. Its cavity is 2 inches wide at the rim, and 1 inch in depth. The nest chiefly consists of a strong rim firmly woven of strips of fine bark, stems of grasses, and fine pine-needles, bound round with flaxen fibres of plants and wool. Around the base a few bits of hornets’ nests, mosses, and lichens are loosely fastened. The nest within is furnished with fine stems and needles, and the flooring is very thin and slight. The egg is somewhat similar in its general appearance to that of D. æstiva, but is smaller and with a ground-color of a different shade of greenish-white. It is oblong-oval in shape, and measures .70 of an inch in length by .50 in breadth. It is thinly marked over the greater portion of its surface with minute dottings of reddish-brown. A ring of confluent blotches of purple and reddish-brown surrounds the larger end.

Dendroica blackburniæ (I, 237). Obtained at Ogden, Utah, in September, 1871, by Mr. Allen (Bull. Mus. Comp. Zoöl. III, No. 5, p. 166).

Dendroica dominica (I, 240). A superb nest of the Yellow-throated Warbler was taken by Mr. Giles, near Wilmington, N. C., in the spring of 1872. The nest was enclosed in a pendent tuft of Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides), and completely hidden within it. Its form is cup-shaped, and it is made of fine roots, mixed with much downy material and a few soft feathers, and, except in its situation, does not differ much from other nests of this genus. Other nests have since been received from Mr. Giles; also a nest of Parula americana similarly situated. Mr. Ridgway, from an examination of the nests, infers that this situation is not constant, but that in other localities where the moss is not found this Warbler may build in thick tufts of leaves near the extremity of drooping branches, or in other similar situations.

Dendroica dominica, var. albilora (I, 241). See Am. Nat, VII, October, 1873, p. 606.

Dendroica graciæ, var. decora (I, 244). See Am. Nat. VII, October, 1873, p. 608.

Dendroica castanea (I, 251). This Warbler is cited by us as exceedingly rare in Eastern Massachusetts, though not unknown. A remarkable exception to this otherwise general rule occurred in the spring of 1872. For several days, in the latter part of May, they were found in great abundance in the vicinity of Boston. As the same unusual occurrence of this species in large numbers was noticed by Mr. Kumlien in Southern Wisconsin, it is probable that along the 42d parallel something occurred to cause a deviation from their usual migrations. The long pause of this species in its spring migrations, and its appearance in large numbers, are not known to have occurred before.

Mr. Salvin (Ibis, April, 1872) expresses the opinion that this Warbler, in its southern migration, does not pause in its flight from the Southern United States to stop in any of the West India Islands, nor in any point of Central America north of Costa Rica. It is by no means rare at Panama during the winter. We may therefore infer that in both its southern and its northern migrations long flights are made, at certain periods, over sections of country in which they do not appear at all, or where only a straggling few are ever seen, and that their abundance in 1872 was exceptional and due to causes not understood.

Dendroica nigrescens (I, 258). Obtained in El Paso County, Colorado; Aiken.

Dendroica occidentalis, D. townsendi, and D. nigrescens (I, 258, 265, 266). While travelling over the Cuyamaca Mountains east of San Diego, in April, 1872, Dr. Cooper found D. occidentalis, for the first time, quite common. They seemed to be still migrating during the last week of April, but perhaps were only moving upwards, being numerous between the elevation of 1,500 and 4,000 feet, while heavy frosts still occurred at the latter height. They probably go in May as high as 6,200 feet, the summits of the highest peaks, which are densely covered by coniferous trees. D. townsendi and D. nigrescens were in company with occidentalis in small flocks, among the oaks, and all seemed to be following an elevated route northward. In 1862, Dr. Cooper found them among the chaparral along the coast, but he regards this as exceptional and probably occasioned by a severe storm in the mountains, as he saw none in 1872 in a spring of average mildness. They occur about Petaluma as early as April 1.

Seiurus ludovicianus (I, 287). Mr. E. Ingersoll met with the nest and eggs of the Large-billed Thrush near Norwich, Conn. The nest was sunk in the ground, in some moss and in the rotten wood underneath the roots of a large tree on the banks of the Yantic River. It was covered over, except just in front, by the roots. The nest was 2½ inches in internal diameter and rather shallow, and was somewhat loosely constructed of fine dry grasses and little dead fibrous mosses. About the nest, but forming no part of it, were several loose leaves. These were chiefly in front of the nest, and served as a screen to conceal it and its occupant. The nest itself was placed under the edge of the bank, about ten feet above the water. The eggs were four in number and were quite fresh. Unblown, they have a beautiful rosy tint, the ground-color is a lustrous white, the egg having a polished surface. They are more or less profusely spotted all over with dots and specks, and a few obscure zigzag markings of reddish-brown of two shades, and umber, with faint touches of lilac and very pale washing of red. These markings are much more thickly distributed about the larger end, but nowhere form a ring. They resemble the eggs of S. aurocapillus, but differ in their somewhat rounder shape, the brilliant polish of their ground, and the greater distinctness of the markings. They varied from .75 to .80 of an inch in length, and from .60 to .62 in breadth.

Geothlypis (I, 295). For a new synopsis of all the species of this genus, see Am. Journ. Science and Arts, Vol. X, December, 1872.

Geothlypis trichas (I, 297). Dr. Cooper found this species wintering in large numbers near San Buenaventura. They frequented the driest as well as the wettest spots.

Geothlypis macgillivrayi (I, 303). We now consider this form a geographical race of S. philadelphia. (See Am. Journ. Science and Arts, Vol. X, December, 1872.)

Myiodioctes pusillus, var. pileolatus (I, 319). See Am. Nat. VII, October, 1873, p. 608.

Setophaga picta (I, 322). This species, not included in the preceding pages among North American Birds, was noticed on only two occasions by Captain Charles Bendire in the vicinity of Tucson, Arizona. This was on the 4th of April, and again on the 12th of September, 1872. He thinks that they unquestionably breed in the mountains to the northward of Tucson. When seen in September they appeared to be moving southward, on their way to their winter quarters. He saw none throughout the summer. (See Am. Nat. VII.) By letter from Mr. Henshaw, we learn that he has obtained this species at Apache, Arizona.

Vireosylvia olivacea (I, 369). Obtained at Ogden, Utah, in September, 1871, by Mr. Allen.

Lanivireo solitarius (I, 373). Dr. Cooper found, April 30, 1870, a male of this species in full plumage and singing delightfully on a ridge above Emigrant Gap on the west slope of the Sierra, about 5,500 feet altitude, and where the snow was still lying in deep drifts. He is confident that he saw the same species at Copperopolis in February, 1864. He thinks there is no doubt that to some extent they winter in the State.

Lanivireo solitarius, var. plumbeus (I, 378). El Paso County, Colorado; Aiken.

Vireo pusillus (I, 391). Dr. Cooper found this species near San Buenaventura as early as March 26, 1872, where it was quite common. On the 22d of April he found a nest pendent between the forks of a dead willow branch. This was five feet from the ground, built on the edge of a dense marshy thicket, of flat strips and fibres of bark, and lined with fine grass, hair, and feathers. There were a few feathers of the Barn Owl, also, on the outside. The nest measured three inches each way. The eggs were laid about the 28th, were four in number, white, with a few small black specks mostly near the larger ends, and measured .69 of an inch in length by .51 in breadth.

Phænopepla nitens (I, 405). Captain Bendire writes me that he found this species common in the vicinity of Tucson, Arizona, during the summer, a few only remaining during the winter; most of these had white edgings on all their feathers, and were probably young of the year. Their flight is described as wavering, something like that of Colaptes mexicanus. While flying they utter a high note, resembling whuif-whuif, repeated several times. He never heard them sing, as they are said to do, although he has watched them frequently. They are very restless, and are always found about the mistletoe, on the berries of which they feed almost exclusively. The nest is saddled on a horizontal branch, generally of a mesquite-tree. It is a shallow structure, about 4 inches across; its inner diameter is 2½ inches, depth ½ an inch. It is composed of fine sticks, fibres of plants, and lined with a little cottonwood down and a stray feather. The first nest was found May 16. This was principally lined with the shells of empty cocoons. The number of eggs was two. Though he found more than a dozen nests with eggs and young, he never found more than two in a nest. Their ground-color varies from a greenish-white to a lavender and a grayish-white, spotted all over with different shades of brown. The spots are all small, and most abundant about the larger end, and vary greatly in their distributions. In size they range from .97 of an inch to .84 in length, and in breadth from .66 to .60.

Collurio ludovicianus, var. robustus (I, 420). See Am. Nat. VII, October, 1873, p. 609.

Certhiola newtoni (I, 427). See Am. Nat. VII, October, 1873, p. 611.

Certhiola caboti (I, 427). See Am. Nat. VII, October, 1873, p. 612.

Certhiola barbadensis, Certhiola frontalis (I, 427). See Am. Nat. VII, October, 1873, p. 612.

Pyranga hepatica (I, 440). Captain Bendire found what he identified as this species breeding near Tucson, Arizona. Its nests and eggs resembled those of P. æstiva. The latter vary in length from 1.02 inches to .95, and in breadth from .70 to .67 of an inch. Their ground-color is a pale light green. Some are sparingly marked over the entire egg with very distinctive and conspicuous blotches of purplish-brown; others are covered more generally with finer dottings of the same hue, and these are so numerous as partly to obscure the ground. In shape the eggs are oblong oval, and are of nearly equal size at either end. This species was also obtained by Mr. Henshaw, at Apache, Arizona.

As no skins of the parent appear to have been preserved, it is not improbable that the bird in question may be really P. æstiva, var. cooperi.

Hesperiphona vespertina, var. montana (I, 450). Two adult males obtained at Waukegan, Illinois, in January, 1873, by Mr. Charles Douglass, are typical examples of the Rocky Mountain form.

Pinicola enucleator (I, 453). Dr. Cooper mentions having shot a fine male of this species near the summit of the Central Railroad Pass at an elevation of about 7,000 feet. It was in a fine orange-red plumage. It was moulting, and appeared to be a straggler.

Pyrrhula cassini (I, 457). Since the publication of the article on this species we learn from Cabanis (Journal für Ornithologie, 1871, 318, 1872, 315) that the species is not uncommon in the vicinity of Lake Baikal, in Siberia, and that it has even been observed in Belgium (Crommelin, Archives Neérlandaises). The bird, therefore, like the Phyllopneuste borealis (P. kennicotti, Baird) and Motacilla flava, is to be considered as Siberian, straggling to continental Alaska in the summer season.

Chrysomitris psaltria (I, 474). See Am. Journ. of Science and Arts, Vol. IV, December, 1872, for a special paper upon the races of this species and their relation to climatic regions.

Chrysomitris psaltria, var. arizonæ (I, 476). On the 7th of May, 1872, Dr. Cooper saw a single specimen (male), which he had no doubt was of this bird, at Encinetos Ranch, thirty miles north of San Diego. It was feeding with other species among dry sunflowers. He also saw another near San Buenaventura in January, 1873.

Loxia “leucoptera, var.” bifasciata (I, 483). At the time when the synopsis of the species of this genus was prepared, we had not seen any specimens of the European White-winged Crossbill. A recent examination of specimens from Sweden has convinced us, however, that the species is entirely distinct from leucoptera, and more nearly related to curvirostra, with the several forms of which it agrees quite closely in the details of form and proportions, as well as in tints, with the exception of the markings of the wing.

Leucosticte tephrocotis (I, 504). The specimens collected by Mr. Allen in Colorado, mentioned in the foot-note on page 505, and there said to be the summer dress of L. tephrocotis, we now believe to be a distinct form, which may be named var. australis, Allen, characterized as follows:—

Leucosticte tephrocotis, var. australis, Allen, MSS. Leucosticte tephrocotis, Allen, Am. Nat. VI, No. 5, May, 1872.—Ib. Bull. Mus. Comp. Zoöl. Vol. III, No. 6, pp. 121, 162.

Char. Similar to var. tephrocotis, but without any gray on the head, the red of the abdomen and wing-coverts bright carmine, instead of dilute rose-color, and the bill deep black, instead of yellow tipped with dusky. Prevailing color raw-umber (more earthy than in var. tephrocotis), becoming darker on the head and approaching to black on the forehead. Nasal tufts white. Wings and tail dusky, the secondaries and primaries skirted with paler; lesser and middle wing-coverts and tail-coverts, above and below, broadly tipped with rosy carmine, producing nearly uniform patches; abdominal region with the feathers broadly tipped with deep carmine or intense crimson, this covering nearly uniformly the whole surface. Bill and feet deep black.

Male (No. 15,724, Mus. C. Z., Mt. Lincoln, Colorado, July 25, 1871; J. A. Allen). Wing, 4.20; tail, 3.10; culmen, .45; tarsus, .70; middle toe, .60.

Female (Mt. Lincoln, July 25; J. A. Allen). Wing, 4.00; tail, 3.00. Colors paler and duller, the red almost obsolete.

Hab. Breeding on Mt. Lincoln, Colorado, above the timber-line, at an altitude of about 12,000 feet. (July, 1872, J. A. Allen.)

Since the descriptions of the several stages of L. tephrocotis were cast, we have received from Mr. H. W. Elliott—Assistant Agent of the United States Treasury Department, stationed at St. Paul’s Island, Alaska, an accomplished and energetic collector—numerous specimens of L. griseinucha in the breeding plumage. The fact that these specimens have the gray of the head as well defined as do examples in the winter plumage, while the red is at the same time much intensified, induces us to modify our views expressed on pages 504, 505, in regard to Mr. Allen’s Colorado specimens, and to regard them as representing a race which must have the head dusky at all seasons, and not a seasonal phase of var. tephrocotis. The winter plumage probably differs from that described above only in the red being of a soft, rather dilute, rosy tint, instead of a harsh bright carmine; the bill is also probably yellow in winter, since in the breeding specimens of griseinucha from Alaska the bill is black, while in winter examples it is yellow, with only the point dusky.

A series of seven fine specimens sent in by Mr. J. H. Batty, the naturalist of Dr. Hayden’s expedition, confirm the validity of this form, and even so much as suggest to us the possibility of its eventually proving a distinct species, more nearly related to L. brunneinucha than to L. tephrocotis. They were collected on some one of the high peaks of Colorado, but as Mr. Batty’s notes have not come to hand we cannot tell which. The specimens are all males, and resemble Mr. Allen’s specimens, except that they are perhaps more highly colored. They all have the throat tinged with carmine, and in some the tinge is very deep,—on one extending over the whole breast and throat, up to the cheeks and bill. We hope to learn soon from Mr. Batty some interesting details regarding this series.