полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

Female. Head plain grayish, without white, black, or rufous; no black on abdomen, which also lacks a decided buff tinge; the cinereous of breast without bluish cast. Crest dusky, less than one inch long. Wing, 4.55; tail, 4.20.

Young. Upper parts ashy brown, minutely and indistinctly mottled transversely with dusky; scapulars and wing-coverts with white shaft-streaks, the former with pairs of dusky spots. Breast and sides with obsolete whitish bars on an ashy ground.

Chick. Dull sulphur-yellowish; a vertical patch, and two parallel stripes along each side of the back (four altogether), black. (Described from Grayson’s plate.)

Hab. Colorado Valley of the United States; north to Southern Utah, and east to Western Texas.

An adult male collected in Southern Utah by Mr. Henshaw of Lieutenant Wheeler’s Expedition differs from all others which we have seen, including a large series from the same locality, in having the abdomen chiefly plumbeous, with a few cloudings of black, in the place of a uniformly black patch. Except in this respect, however, it does not differ at all from other adult male specimens.

Habits. Gambel’s Partridge was obtained by Dr. Kennerly, near San Elizario, Texas, and on Colorado River, California, by Mr. A. Schott, and also by Dr. Kennerly. It was not observed by Dr. Kennerly until he reached the valley of the Rio Grande, nor did he meet with any farther west, in any part of Mexico, than San Bernardino, in Sonora. Though closely resembling in its habits the Scaly Partridge (Callipepla squamata), and in some instances occupying the same districts, he never found the two species together.

According to Mr. J. H. Clark, this species was not met with east of the Rio Grande, nor farther south than Presidio del Norte. Unlike the squamata, it is very common for this species to sit on the branches of trees and bushes, particularly the male, where the latter is said to utter the most sad and wailing notes. They are so very tame as to come about the Mexican towns, the inhabitants of which, however, never make any effort to capture them. They only inhabit wooded and well-watered regions, and are said to feed indifferently on insects or on berries; in summer they make the patches of Solanum their home, feeding on its quite palatable fruit. When flushed, this Quail always seeks the trees, and hides successfully among the branches.

Dr. Kennerly found this beautiful species in great numbers during the march of his party up the Rio Grande. Large flocks were continually crossing the road before them, or were seen huddled together under a bush. After passing the river he met with them again so abundantly along Partridge Creek as to give rise to the name of that stream. Thence to the Great Colorado he occasionally saw them, but after leaving that river they were not again seen. They are said to become quite tame and half domesticated where they are not molested. When pursued, they can seldom be made to fly, depending more upon their feet as a mode of escape than upon their wings. They run very rapidly, but seldom, if ever, hide, and remain close in the grass or bushes in the manner of the eastern Quail.

From Fort Yuma, on the Colorado River, to Eagle Springs, between El Paso and San Antonio, where he last saw a flock of these birds, Dr. Heermann states he found them more or less abundant whenever the party followed the course of the Gila, or met with water-holes or streams of any kind. Although they frequent the most arid portions of the country, where they find a scanty subsistence of grass-seed, mesquite leaves, and insects, they yet manifest a marked preference for the habitations of man, and were much more numerous in the cultivated fields of Tucson, Mesilla Valley, and El Paso. Towards evening, in the vicinity of the Mexican villages, the loud call-notes of the male birds may be heard, gathering the scattered members of the flocks, previous to issuing from the cover where they have been concealed during the day. Resorting to the trails and the roads in search of subsistence, while thus engaged they utter a low soft note which keeps the flock together. They are not of a wild nature, often permit a near approach, seldom fly unless suddenly flushed, and seem to prefer to escape from danger by retreating to dense thickets. In another report Dr. Heermann mentions finding this species in California on the Mohave desert, at the point where the river empties into a large salt lake forming its terminus. The flock was wild, and could not be approached. Afterwards he observed them on the Big Lagoon of New River. At Fort Yuma they were quite abundant, congregating in large coveys, frequenting the thick underwood in the vicinity of the mesquite-trees. Their stomachs were found to be filled with the seeds of the mesquite, a few grass-seeds, and the berries of a parasitic plant. On being suddenly flushed these birds separate very widely, but immediately upon alighting commence their call-note, resembling the soft chirp of a young chicken, which is kept up for some time. The alarm over, and the flock once more reunited, they relapse into silence, only broken by an occasional cluck of the male bird. Once scattered they cannot be readily started again, as they lie close in their thick, bushy, and impenetrable coverts. Near Fort Yuma the Indians catch them in snares, and bring them in great numbers for sale.

Dr. Samuel W. Woodhouse first met with this species on the Rio Grande, about fifty miles below El Paso, up to which place it was extremely abundant. It was by no means a shy bird, frequently coming about the houses; and he very often observed the males perched on the top of a high bush, uttering their peculiarly mournful calls. He found it in quite large flocks, feeding principally on seeds and berries. It became scarce as he approached Doña Ana, above which place he did not meet with it again. He again encountered it, however, near the head of Bill Williams River, and afterwards on the Tampia Creek, and it was exceedingly abundant all along the Great Colorado. He was informed that they are never found west of the Coast Range, in California. About Camp Yuma, below the mouth of the Gila River, they were very abundant and very tame, coming quite near the men, and picking up the grain wasted by the mules. They are trapped in great numbers by the Indians.

This Quail is given by Mr. Dresser as occurring in Texas, but not as a common bird, and only found in certain localities. At Muddy Creek, near Fort Clark, they were not uncommon, and were also found near the Nueces River.

Dr. Coues (Ibis, 1866), in a monograph upon this species, describes its carriage upon the ground as being firm and erect, and at the same time light and easy, and with colors no less pleasing than its form. He found them to be exceedingly abundant in Arizona, and soon after his arrival in the Territory he came upon a brood that was just out of the egg. They were, however, so active, and hid themselves so dexterously, that he could not catch one. This was late in July, and throughout the following month he met broods only a few days old. The following spring he found the old birds mated by April 25, and met with the first chick on the first of June. He infers that this species is in incubation during the whole of May, June, July, and a part of August, and that they raise two, and even three, broods in a season.

A single brood sometimes embraces from fifteen to twenty young, which by October are nearly as large as their parents. While under the care of the latter they keep very close together, and when alarmed either run away rapidly or squat so closely as to be difficult to flush, and, when forced up, they soon alight again. They often take to low limbs of trees, huddle closely together, and permit a close approach. The first intimation that a bevy is near is a single note repeated two or three times, followed by the rustling of leaves as the flock start to run.

These birds are said to be found in almost every locality except thick pine-woods without undergrowth, and are particularly fond of thick willow copses, heavy chaparral, and briery undergrowth. They prefer seeds and fruit, but insects also form a large part of their food. In the early spring they feed extensively on the tender fresh buds of young willows, which give to their flesh a bitter taste.

This Quail is said to have three distinct notes,—the common cry uttered on all occasions of alarm or to call the bevy together, which is a single mellow clear “chink,” with a metallic resonance, repeated an indefinite number of times; then a clear, loud, energetic whistle, resembling the syllables killink-killink, chiefly heard during the pairing-season, and is analogous to the bob-white of the common Quail; the third is its love-song, than which, Dr. Coues adds, nothing more unmusical can well be imagined. It is uttered by the male, and only when the female is incubating. This song is poured forth both at sunrise and at sunset, from some topmost twig near the spot where his mate is sitting on her treasures; and with outstretched neck, drooping wings, and plume negligently dangling, he gives utterance to his odd, guttural, energetic notes.

The flight of these birds is exceedingly rapid and vigorous, and is always even and direct, and in shooting only requires a quick hand and eye.

In his journey from Arizona to the Pacific, Dr. Coues found these birds singularly abundant along the valley of the Colorado; and he was again struck with its indifference as to its place of residence, being equally at home in scorched mesquite thickets, dusting itself in sand that would blister the naked feet, the thermometer at 117° Fah. in the shade, and in the mountains of Northern Arizona, when the pine boughs were bending under the weight of the snow. He also states that Dr. Cooper, while at Fort Mohave, brought up some young Gambel’s Quails by placing the eggs under a common Hen, and found no difficulty in domesticating them, so that they associated freely with the barnyard fowls. The eggs, he adds, are white, or yellowish-white, with brown spots, and were hatched out in twenty-four days. The nest is said to be a rather rude structure, about eight inches wide, and is usually hidden in the grass. The eggs number from twelve to seventeen.

Captain S. G. French, quoted by Mr. Cassin, writes that he met with this species on the Rio Grande, seventy miles below El Paso, and from that point to the place named their numbers constantly increased. They appeared to be partial to the abodes of man, and were very numerous about the old and decayed buildings, gardens, fields, and vineyards around Presidio, Isoleta, and El Paso. During his stay there in the summer of 1851, every morning and evening their welcome call was heard all around; and at early and late hours they were constantly to be found in the sandy roads and paths near the villages and farms. In the middle of the hot summer days, however, they rested in the sand, under the shade and protection of the thick chaparral. When disturbed, they glided through the bushes very swiftly, seldom resorting to flight, uttering a peculiar chirping note. The parents would utter the same chirping cry whenever an attempt was made to capture their young. The male and female bird were always found with the young, showing much affection for them, and even endeavoring to attract attention away from them by their actions and cries.

Colonel McCall (Proc. Phil. Ac., June, 1851) also gives an account of this bird, as met with by him in Western Texas, between San Antonio and the Rio Grande River, as well as in New Mexico. He did not fall in with it until he had reached the Limpia River, a hundred miles west of the Pecos, in Texas, where the Acacia glandulosa was more or less common, and the mesquite grasses and other plants bearing nutritious seeds were abundant. There they were very numerous and very fat, and much disposed to seek the farms and cultivate the acquaintance of man. About the rancho of Mr. White, near El Paso, he found them very numerous, and, in flocks of fifty or a hundred, resorting morning and evening to the barnyard, feeding around the grain-stacks in company with the poultry, and receiving their portion from the hand of the owner. He found them distributed through the country from the Limpia to the Rio Grande, and along the latter river from Eagle Spring Pass to Doña Ana.

The same careful observer, in a communication to Mr. Cassin, gives the western limit of this species. He thinks it is confined to a narrow belt of country between the 31st and 34th parallels of latitude, from the Pecos River, in Texas, to the Sierra Nevada and the contiguous desert in California. It has not been found on the western side of these mountains. Colonel McCall met with it at Alamo Mucho, forty-four miles west of the Colorado River. West of this stretches a desolate waste of sand,—a barrier which effectually separates this species from its ally, the California Quail.

This species is known to be abundant in the country around the sources of the Gila River, and has also been found along that river from the Pimo villages to its mouth, and there is no doubt that it inhabits the entire valley of the Gila. It was also common along the Colorado River, as far as the mouth of the Gila, and has been met with in that valley as high up as Tampia Creek, latitude 34°.

Colonel McCall regards this species as less wild and vigilant than the California species. It is later in breeding, as coveys of young California Quails were seen, one fourth grown, June 4, while all the birds of Gambel’s were without their young as late as June 16. The voice of the male at this season is described as strikingly rich and full. The cry may be imitated by slowly pronouncing in a low tone the syllables kaa-wale, kaa-wale. When the day is calm and still, these notes may be heard to a surprising distance. This song is continued, at short intervals, in the evening, for about an hour. Later in the season when a covey is dispersed, the cry for reassembling is said to resemble qua-el qua-el. The voice of this bird at all seasons bears a great resemblance to that of the California Quail, but has no resemblance to that of the eastern Ortyx virginiana. In their crops were found the leaves of the mesquite, coleopterous insects, wild gooseberries, etc.

An egg of this species, taken by Dr. Palmer at Camp Grant, measures 1.25 inches in length by 1.00 in breadth. The ground-color is a cream white, beautifully marked with ragged spots of a deep chestnut. In shape it closely corresponds with the egg of the California Partridge.

Genus CALLIPEPLA, Wagler

Callipepla, Wagler, Isis, 1832. (Type, Ortyx squamata, Vig.)

Gen. Char. Head with a broad, short, depressed tufted crest of soft, thick feathers springing from the vertex. Other character, as in Lophortyx. Sexes similar.

The single United States species is of a bluish tint, without any marked contrast of color. The feathers of the neck, breast, and belly have a narrow edging of black.

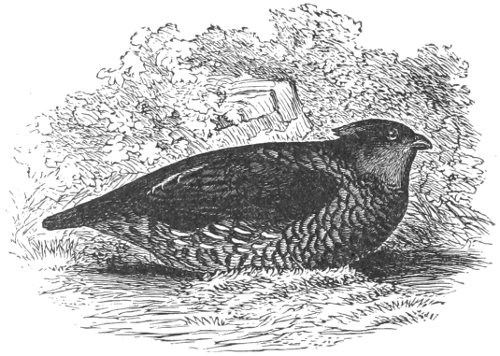

Callipepla squamata, GraySCALED OR BLUE PARTRIDGEOrtyx squamatus, Vigors, Zoöl. Journ. V, 1830, 275.—Abert, Pr. A. N. Sc. III, 1847, 221. Callipepla squamata, Gray, Gen. III, 1846, 514.—M’Call, Pr. A. N. Sc. V, 1851, 222.—Cassin, Ill. I, v, 1854, 129; pl. xix.—Gould, Mon. Odont. pl. xix.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 646.—Ib. Mex. B. II, Birds, 23.—Gray, Cat. Brit. Mus. V, 1867, 78.—Heerm. X, C, 19.—Coop. Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 556. Callipepla strenua, Wagler, Isis, XXV, 1832, 278. Tetrao cristata, De la Llave, Registro trimestre, I, 1832, 144.

Sp. Char. Head with a full, broad, flattened crest of soft elongated feathers. Prevailing color plumbeous-gray, with a fine bluish cast on jugulum and nape, whitish on the belly, the central portion of which is more or less tinged with brownish; sometimes a conspicuous abdominal patch of dark rusty, the exposed surface of the wings tinged with light yellowish-brown, and very finely and almost imperceptibly mottled. Head and throat without markings, light grayish-plumbeous; throat tinged with yellowish-brown. Feathers of neck, upper part of back, and under parts generally, except on the sides and behind, with a narrow but well-defined margin of blackish, producing the effect of imbricated scales. Feathers on the sides streaked centrally with white. Inner edge of inner tertials, and tips of long feathers of the crest, whitish. Crissum rusty-white, streaked with rusty. Female similar. Length, 9.50; wing, 4.80; tail, 4.10.

Hab. Table-lands of Mexico and valley of Rio Grande of Texas. Most abundant on the high broken table-lands and mesquite plains.

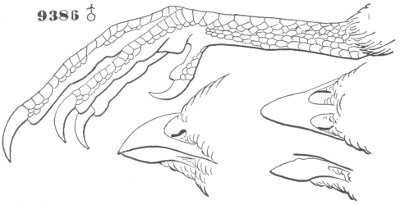

9386 ♂

Callipepla squamata.

Habits. This bird was first described as a Mexican species in 1830 by Mr. Vigors. For a long while it has been an extremely rare species in collections, and its history, habits, and distribution remained unknown until the explorations of the naturalists made in the surveys under the direction of the national government. It was first noticed within the territory of the United States by Lieutenant Abert, Topographical Engineer, who, in his Report of the examination of New Mexico, furnishes several notes in relation to this species. In November, 1846, he mentions that, after having passed through Las Casas, while descending through a crooked ravine strewed with fragments of rocks, he saw several flocks of this species. They were running along with great velocity among the clumps of the kreosote plant. At the report of the gun only three or four rose up, the rest seeming to depend chiefly on their fleetness of foot. Their stomachs were found to be filled with grass-seeds and hemipterous insects.

Callipepla squamata.

Captain S. G. French, in notes quoted by Mr. Cassin, mentions meeting with these birds, in the same year, near Camargo, on the Rio Grande. At Monterey none were seen; but on the plains of Agua Nueva, a few miles south of Saltillo, they were observed in considerable numbers. He afterwards met with them on the Upper Rio Grande, in the vicinity of El Paso. Though found in the same section of country with Gambel’s Quail, they were not observed to associate together in the same flock. Their favorite resorts were sandy chaparral and mesquite bushes. Through these they ran with great swiftness, resorting only, when greatly alarmed by a sudden approach, to their wings. They were very shy, and were seldom found near habitations, though once a large covey ran through his camp in the suburbs of El Paso.

Colonel McCall (Proc. Phil. Ac. V, p. 222) mentions meeting with this species throughout an extended region, from Camargo, on the Lower Rio Grande, to Santa Fé. They were most numerous between the latter place and Doña Ana, preferring the vicinity of watercourses to interior tracts. They were wild, exceedingly watchful, and swift of foot, eluding pursuit with surprising skill, scarcely ever resorting to flight even on the open sandy ground. For the table they are said to possess, in a high degree, the requisites of plump muscle and delicate flavor.

In a subsequent sketch of this species, quoted by Mr. Cassin, the same writer gives as the habitat the entire valley of the Rio Grande,—a territory of great extent from north to south, and embracing in its stretch between the Rocky Mountains and the Gulf of Mexico every variety of climate. This entire region, not excepting even the mountain valleys covered in winter with deep snow, is inhabited by it. It was found by him from the 25th to the 38th degree of north latitude, or from below Monterey, in Mexico, along the borders of the San Juan River, as high up as the Taos and other northern branches of the Rio Grande. He also found it near the head of the Riado Creek, which rises in the Rocky Mountains and runs eastwardly to the Canadian.

Wherever found, they are always resident, proving their ability to endure great extremes of heat and cold. In swiftness of foot, no species of this family can compete with them. When running, they hold their heads high and keep the body erect, and seem to skim over the surface of the ground, their white plume erected and spread out like a fan.

On the Mexican side of the Rio Grande this species is found farther south than on the western bank, owing to the rugged character of the country. In Texas its extreme southern point is a little above Reinosa, on the first highlands on the bank.

Don Pablo de la Llave, a Mexican naturalist, states, in an account of this species (Registro Trimestre, I, p. 144, Mexico, 1832), that he attempted its domestication in vain. In confinement it was very timid, all its movements were rapid, and, although he fed his specimens for a long time each day, they seemed to become more wild and intractable. It was found by him in all the mesquite regions of Northern Mexico.

Specimens of this Partridge were taken near San Pedro, Texas, by Mr. J. H. Clark, and in New Leon, Mexico, by Lieutenant Couch. According to Mr. Clark, they are not found on the grassy prairies near the coast. He met with them on Devil’s River, in Texas, where his attention was at first directed to them by their very peculiar note, which, when first heard, suggested to him the cry of some species of squirrel. In the valley of the Lower Rio Grande he also met with these birds in companies of a dozen or more. Their food, on the prairies, appeared to be entirely insectivorous; while on the Lower Rio Grande all the specimens that were procured had their bills stained with the berries of the opuntia. They were not shy, and would rather get out of the way by running than by flying. At no time, and under no circumstances, were they known to alight in bushes or in trees. They were only known to make mere scratches in the ground for nests, and their situations were very carelessly selected. Young birds were found in June and in July.

Lieutenant Couch first met with this species about sixty leagues west of Matamoras, and not until free from the prairies and bottom-land. It was occasionally noticed, apparently associating with the Ortyx texana, to which it is very similar in habit.

Dr. Kennerly found them everywhere where there was a permanent supply of fresh water, from Limpia Creek, in Texas, to San Bernardino, in Sonora. They were met with on the mountain-sides, or on the hills among the low mesquite-bushes and barrea. They apparently rely more upon their legs than upon their wings, ascending the most precipitous cliffs or disappearing among the bushes with great rapidity.

The most western point at which Dr. Heermann observed this species was the San Pedro River, a branch of the Gila, east of Tucson. There a flock of these birds ran before him at a quick pace, with outstretched necks, heads elevated, crests erect and expanded, and soon disappeared among the thick bushes that surrounded them on all sides. After that they were seen occasionally until they arrived at Lympia Springs. Lieutenant Barton informed Dr. Heermann that he had procured this species near Fort Clark, one hundred and twenty miles west of San Antonio, where, however, it was quite rare. It was found abundantly on the open plains, often starting up before the party when passing over the most arid portions of the route. They also seemed partial to the prairie-dog villages. These, covering large tracts of ground destitute of vegetation, probably offered the attraction of some favorite insect.

Dr. Woodhouse met with this species on only one occasion, as the party was passing up the Rio Grande, at the upper end of Valleverde, on the west side of the river, on the edge of the sand-hills, feeding among the low bushes. They were exceedingly shy and quick-footed. He tried in vain to make them fly, and they evidently preferred their feet to their wings as a means of escape. He was told that they were found above Santa Fé.

Mr. Dresser found this species on the Rio Grande above Roma, and between the Rio Grande and the Nueces they were quite abundant; wherever found, they seemed to have the country to themselves to the exclusion of other species. He reports them as very difficult to shoot, for the reason that, whenever a bevy is disturbed, the birds scatter, and, running with outstretched necks and erected crests, dodge through the bushes like rabbits, so as soon to be out of reach. He has thus seen a flock of ten or fifteen disappear so entirely as to render it impossible to obtain a single one. If left undisturbed, they commence their call-note, which is not unlike the chirp of a chicken, and soon reunite. It was utterly out of the question to get them to rise, and the only way to procure specimens was to shoot them on the ground. Near the small villages in Mexico he found them very tame; and at Presidio, on the Rio Grande, he noticed them in a corral, feeding with some poultry. He did not meet with their eggs, but they were described to him, by the Mexicans, as dull white, with minute reddish spots.