полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

Pipilo chlorurus (II, 131). Dr. Cooper met with none of this species in the Sierra Nevada between 3,000 and 7,000 feet elevation in April, 1870, when they were leisurely working their way up from the lower country; but in July he found them from Truckee, 6,000 feet on the east slope, up to the summit, 7,000 feet, but not higher. They were then feeding half-grown young. Dr. Albert Kellogg found a nest on the ground, with four eggs, spotted near the larger end on a bluish ground. The males were still singing occasionally and very melodiously, and had the same cry of alarm or anger as the Pipilo erythropthalmus. Dr. Cooper also met with this species at Clear Lake, near the end of September, showing that they probably breed in the northern Coast Range.

Dolichonyx oryzivorus (II, 149). Specimens from every portion of the Plains, and west to the Great Basin, have the black intenser and more continuous, the nuchal patch clear ochraceous-white, the scapulars and rump unshaded white, and the white of the back confined to a median line. The bill and feet are also jet-black, instead of horn-color. They constitute var. albinucha, Ridgway.

Icterus cucullatus (II, 193). Except in the materials, which difference may be more local than specific, the nests of this species are hardly distinguishable from those of I. spurius. A nest from Cape St. Lucas (S. I. No. 4,954), collected May, 1860, by Mr. Xantus, is basket-shaped and pendulous, suspended on two sides to the numerous twigs of each fork of a drooping branch. In structure it is exactly like that of I. spurius, and is composed of dry wiry grasses, lined scantily with vegetable down. The length is six inches, lower side of aperture only two and a half inches from the bottom. Another (S. I. No. 1,940) taken May 20, 1859, at San José, Lower California, by Mr. Xantus, is a very elaborately wrought basket-shaped nest. The circumference of the circular rim is much less than the greatest girth of the nest. The lower walls and base of the nest are very thick. The whole is composed of fine wiry grasses and scantily lined with vegetable down and soft flaxy fibres. The external diameter is 5.00 inches, the internal 2.10, height about 3.00, and the depth of the cavity 2.80.

Captain Charles Bendire met with this species in Southern Arizona. It was first noticed by him on the 15th of April, but he thinks they had arrived nearly ten days previously, and that the date of their coming may be given as during the first week of April. He describes it as a shy, active, and restless bird, generally frequenting the extreme tops of the tallest cottonwood-trees near the borders of the watercourses, which, however, are usually dry. There the bird flutters through the dense foliage in search of insects, and is scarcely ever seen for more than an instant at a time. It commences building about the first of June. The nest is suspended from the extremities of the lower branches of an ash, walnut, mesquite, or cottonwood tree, and is exclusively composed of fine wire-like grasses, which are made use of while green and pliable, and sparsely lined with the silky fibres of a species of Asclepias. These grasses are interlaced in such a complicated manner as to form, even when dry, a very strong structure. The dimensions of a nest are: Inner diameter, three inches; inside depth the same; outside from five and a half to four inches wide and about four deep. The eggs are from two to four in number, usually three, are of a pale bluish-white ground, spotted with dark lilac and umber-brown about the larger end. The largest eggs measure one inch by .64. Captain Bendire adds that he cannot regard this Oriole as a fine singer. Besides a usual chattering note resembling the syllables char-char-char, frequently repeated, it has a call-note something like hui-wit, which is also several times repeated.

Icterus baltimore (II, 195). Extends its range westward to the Rocky Mountains. Collected in El Paso County, Colorado, by Mr. Aiken.

Icterus bullockii (II, 199). Extends eastward to Eastern Kansas, where it is not uncommon. (See Snow’s Catalogue of the Birds of Kansas, 1873.)

Corvus cryptoleucus (II, 242). According to Mr. Aiken this species is abundant, and nearly replaces C. carnivorus along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains, as far north as Cheyenne.

Captain Bendire found this a resident species in Southern Arizona, and met with two nests at the base of the St. Catharine Mountains, near Tucson. One of these contained three, the other four eggs. These he described as very light colored, so pale that if mixed with hundreds of others of this family they could be picked out without difficulty. Their ground-color is said to be a very pale green, with darker markings running more into lines than spots; in fact, very few spots were found on either set. The size of the largest was 1.85 inches by 1.33, that of the largest 1.70 by 1.19. They were not common in the vicinity of Tucson.

Cyanura (II, 271). For a special treatment of the races of C. stelleri, see Am. Journ. Science and Arts, January, 1873.

Cyanocitta californica (II, 298). Dr. Cooper has ascertained that this species does occur on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, but lower down than the region he visited in 1863. He found a few at Verdi, close to the eastern boundary-line of California, at about 4,500 feet elevation, in July, 1870. He saw none elsewhere.

Tyrannus vociferans (II, 327). Captain Bendire writes that this species arrives in the neighborhood of Tucson about the middle of April, but does not commence nesting until the middle of June. All the nests he found were difficult to get at, being generally placed on a branch of a large cottonwood-tree, and at a distance from the trunk. The nest is described as very large for the size of the bird, composed of sticks, weeds, dry grasses, and lined with hair, wool, and the inner soft fibres of bark of the cottonwood. The usual complement of eggs is three, seldom four. They measure from 1.00 by .75 to 1.10 by .80 of an inch, are of a creamy-white color, with large isolated spots of a reddish-brown, scattered principally about the larger end.

Myiarchus (II, 329). For a discussion of the races of M. lawrencii considered in their relation to climatic color-variation, see Am. Journ. Science and Arts, December, 1872.

Sayornis (II, 339). The outlines of species of Sayornis given below are additional to those already published.

Empidonax brunneus (II, 363). Specimens in the collection of the Boston Society bear the MSS. name of E. olivus. But we cannot find a reference to this name.

Empidonax minimus (II, 372). Has been collected in El Paso County, Colorado, by Mr. Aiken.

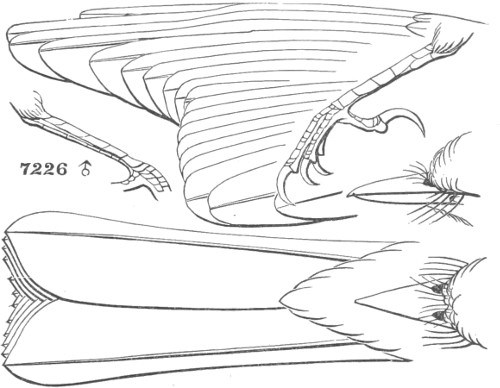

7226 ♂

Sayornis sayus.

2707

Sayornis fuscus.

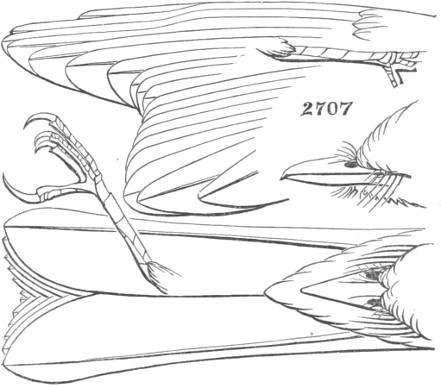

10028 ♀

Sayornis nigricans.

Empidonax obscurus (II, 381). Dr. Cooper found a few of this species wintering in a large grove of balsam, poplars, and willows, which retained most of their old leaves till spring, near San Buenaventura. Those shot were remarkably gray, and were supposed to have been blown down from the borders of the desert by the violent northeast-wind.

Pyrocephalus mexicanus (II, 387). Captain Bendire found the Red Flycatcher quite abundant in Southern Arizona, where they breed as early as April. They were most common in the neighborhood of Reledo Creek, near Tucson, and were generally found in the neighborhood of water. Their nests were in various situations, in one instance in a cottonwood-tree thirty feet from the ground, in another in the forks of a mesquite not more than ten feet from the ground. The nests were small, slight, and loosely made, and not readily preserved. They were made externally of twigs, fine bark, stems of plants, etc., and lined with hair and feathers. The usual number of eggs was three, and never more. Except in size these bear a close resemblance to the eggs of Milvulus forficatus. Their ground is a rich cream-color, to which the deep purplish-brown markings with which they are blotched imparts a slight tinge of red. These markings are few, bold, and conspicuous, and encircle the larger end with an almost continuous ring. In shape they are of a roundish oval, and measure .66 of an inch in length by .55 in breadth. The nest and eggs of this species were also obtained at Cape St. Lucas by Mr. John Xantus, and the eggs correspond. Dr. Cooper found two male birds of this species in a grove near the mouth of the Santa Clara River, six miles from San Buenaventura, in October, 1872. They had obtained their perfect plumage, but seemed to be young birds. They hunted insects much like a Sayornis, and uttered only a faint chirp.

Chordeiles popetue, var. minor (II, 400). Specimens from Miami, Florida, collected by Mr. Maynard, agree very nearly with typical examples of var. minor from Cuba, both in size and color, and should possibly be referred to that race. A male (7,414, Mus. C. J. M.) measures: wing, 7.00; tail, 4.15. The colors are those of var. popetue, with less rufous than in the single specimen of minor with which it has been compared.

Chordeiles texensis (II, 406). Dr. Cooper shot a single specimen of this species near San Buenaventura, April 18, 1873.

Antrostomus carolinensis (II, 410). This species has been detected by Mr. Ridgway in Southern Illinois (Wabash County), where it is a rare summer sojourner.

Panyptila melanoleuca (II, 424). Dr. Cooper saw many of this species in the cañon of Santa Anna, flying about inaccessible cliffs of sandstone, where they doubtless had nests, May 20. He saw also them near San Buenaventura, August 25, when they came down to the valley from the sandstone cliffs ten miles distant. They afterwards hunted insects almost daily near the coast, flying high during the calm morning, but when there were sea-breezes flying low and against it. After a month they disappeared, and none were seen until December 14, when they were again seen until the 20th. None were seen during the rains, or until February 26, when they reappeared, and after April 5 they retired to the mountains.

Nephœcetes niger (II, 429). Dr. Cooper informs us that a fine specimen of this rare bird was taken at San Francisco in the spring of 1870, and brought to Mr. F. Gruber. It had, from some cause, been driven to alight on the ground, from which it was not able to rise, and was taken alive. The exact date was not noted.

Chætura vauxi (II, 435). Dr. Cooper states that in the spring of 1873 this Swift appeared as early as April 22 near San Buenaventura. The year before he first saw them near San Diego on the 26th.

Geococcyx californianus (II, 472). Has been found in El Paso County, Colorado, by Mr. Aiken.

Picus gairdneri (II, 512). Four eggs of this Woodpecker were taken by Mr. William A. Cooper near Santa Cruz, Cal., from a hole in a tree, one side of which was much decayed. Four is said to be the usual number of their eggs, although five were found in one instance. The eggs resemble those of P. pubescens, and measure .75 of an inch in length by .57 in breadth.

Sphyropicus varius (II, 539). Collected in El Paso County, Colorado, by Mr. Aiken.

Centurus uropygialis (II, 558). Captain Bendire found this Woodpecker the most common of the family in the vicinity of Tucson, Arizona, where it was resident throughout the year. Like nearly all of its kindred, it is an exceedingly noisy bird. It appears to be a resident species throughout the year in all the southern portions of the Territory. Its favorite localities for nesting appear to be in the gigantic trunks of the large Cereus giganteus, which plants are called by the natives Suwarrows. These are easily excavated, and form a remarkably safe place in which to rear their young ones, on account of the many thorns with which these cacti are protected. Their eggs are usually four in number, but sometimes are only two, and resemble those of all the other kinds of Woodpeckers in their color and in their rounded oval shape. They average .98 of an inch in length and .76 in breadth. Usually two, and occasionally even three, broods are raised in a season.

Strix pratincola (III, 13). Dr. Cooper informs us that, though most of these Owls are resident in California south of latitude 35°, there is a migration southward in fall from the north. Great numbers of them appeared near San Buenaventura about October 20, 1872, for a few days, and most of them went still farther southward. They return north about the first of April. On the 12th of April he found a nest built four feet up in a pepper-tree (Schinus molle), forming part of a hedge, composed of coarse sticks, straws, and dry horse-dung inside, shallow but strongly built, and containing two eggs.

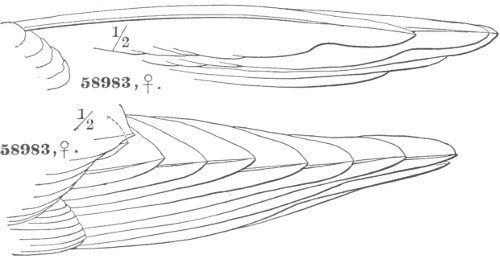

Falconidæ (III, 103). The following outlines of the Falconidæ were omitted in their proper places.

58983, ♀. ½

58983, ♀. ½

58983. Falco richardsoni.

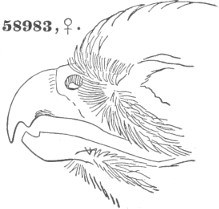

58983, ♀.

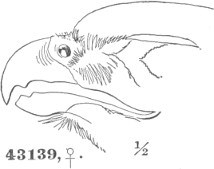

43139, ♀. ½

43139. Falco gyrfalco, var. sacer.

5482, ♀. ¼

5482. Falco lanarius, var. polyagrus.

58983, ♀.

Chamæpelia passerina (III, 389). Dr. Cooper states that an individual of this species was killed by Mr. Lorquin at San Francisco, in May, 1870. Mr. Lorquin also obtained several at San Gabriel, Los Angeles County, several years previous.

Tetrao obscurus (III, 421). Dr. Cooper found this species in April, 1870, at the edge of the melting snow, near Cisco, about 6,000 feet altitude. They were still more numerous at Emigrant Gap, 5,300 feet altitude, where snow lay only in patches, and at Truckee, on the east slope, where there was no snow, and where he found two of their eggs in a deserted nest within sight of the town. In July he found them near Verdi, near the State line. This is the limit of their range. They also frequent the edge of perpetual snow, at an elevation of 9,000 feet, more numerously than below.

Ortyx virginianus, var. floridanus (III, 469, footnote). Specimens from Miami, Fla., exhibit the peninsular extreme of this species. They are altogether more like var. cubanensis than like virginianus proper, yet they differ uniformly in such essential respects from the Cuban form that they merit a distinctive name. The characteristic features of this form are the following:—

Char. Above, with dark bluish-gray prevailing, only the anterior part of the back being washed, or mixed, with reddish; scapulars and tertials quite conspicuously bordered with whitish. The whole gray surface more or less mottled or barred with black. The head-stripes are nearly uniformly black, with only a little rusty mixed in the occiput; the black gular collar is much extended, encroaching on the throat anteriorly, so as to leave only an inch, or less, of white, and posteriorly invades the jugulum, so that there is more than an inch of continuous black, and over this distance where black predominates. The entire abdomen, anal region, and breast are heavily barred with black, the black bars on the breast almost equalling the white ones in width. The sides, flanks, and crissum are nearly uniform rufous, the feathers of the former with white edges, broken by the extensions of the black streak which runs inside the white, while the latter have heavy black medial streaks and white terminal spaces.

The female is similar, except in the color of the head, which is exactly that of var. texanus.

Wing, ♂, 4.30–4.40; ♀, 4.35. Culmen, .60–.65; tarsus, 1.15–1.20; middle toe, 1.05–1.10.

Oreortyx pictus (III, 475). Dr. Cooper found these birds already paired near the summit of the Sierra Nevada, where the snow was but half melted off, and they scarcely descended below the limits of the snow in the coldest weather. In July he saw young birds just hatched near Truckee, at an elevation of 6,000 feet. This was on the 24th. On the 28th another brood, a little older, was seen at the foot of Mt. Stanford, about 8,000 feet above the sea. Most of the broods, however, were nearly fledged at that time. Dr. Cooper also mentions that he found this Quail not rare in the mountains east of San Diego above an elevation of 3,800 feet. He thought, also, that he heard this bird in the Santa Anna range east of Annaheim. It also exists in the Santa Inez Mountains, sixteen miles east of San Buenaventura, at an altitude of from 3,000 to 4,000 feet. It seems to be confined to the zone of coniferous trees, rarely if ever coming below them. Mr. Henshaw has obtained this species at Apache, in Arizona.

Lophortyx gambeli (III, 482). Captain Bendire found this Quail breeding in the vicinity of Tucson, in Arizona, near Rillito Creek, occasionally nesting in situations above the ground. One nest, seen June 7, 1872, contained three fresh eggs. It was two feet above the ground, on a willow stump, and in an exposed place, near the creek. The nest was composed of the leaves of the cottonwood-tree. In some instances he found as many as eighteen eggs in one nest. These closely resemble the eggs of the California Quail, so much so as to be hardly distinguishable from them. They are all of a rounded oval shape, sharply tapering at one end, and quite obtuse at the other. They measure 1.24 inches in length by one inch in their largest breadth. Their ground-color varies from a deep cream to a light drab. Some are sparingly marked with large and well-defined spots, most of them circular in shape, and of a rich purplish-brown color. In others the whole surface is closely sprinkled with minute spots of yellowish-brown, intermingled with which are larger spots of a dark purple. This species was obtained in Southern Utah by Mr. Henshaw.

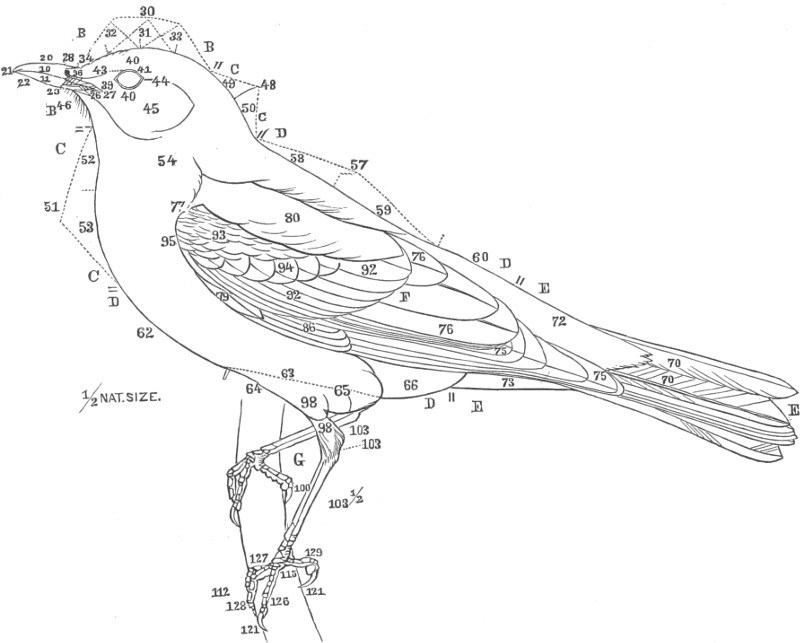

II.

EXPLANATION OF TERMS USED IN DESCRIBING THE EXTERNAL FORM OF BIRDS

½ nat. size.

Turdus migratorius, L.

REFERENCES TO THE FIGURE

N. B. In the figure the adjacent regions are separated by a double bar, with the letters belonging to each affixed.

A. The body in general.

B. The region of the head.

C. The region of the neck.

D. The region of the trunk.

E. The region of the tail.

F. The region of the wings.

G. The region of the legs.

H. The feathers.

Note.—I am under obligations to Professor Sundevall of Stockholm and Dr. Sclater of London for assistance in correcting and improving the present article.—S. F. Baird.

B. Head9. Bill in general.

10. Maxilla.

11. Mandible.

20. Ridge.

21. Tip of maxilla.

22. Keel.

23. Angle of chin.

27. Angle of mouth.

28. Commissure.

28½. Nostrils.

30. Cap (pileus), includes 32, 33.

31. Crown (vertex).

32. Front head (sinciput).

33. Hind head (occiput).

34. Forehead.

36. Frontal points.

39. Lores.

40. Ophthalmic region.

41. Orbits.

42. Cheeks.

43. Eyebrows.

44. Temples.

45. Parotics.

46. Chin.

C. Neck48. Hind neck (includes 49, 50).

49. Nape.

50. Scruff.

51. Fore neck (includes 52, 53).

52. Throat.

53. Jugulum.

54. Side neck.

D. Trunk or Body57. Back (includes 58, 59).

58. Upper back.

59. Lower back.

60. Rump.

61. Mantle (back and wings together).

62. Breast.

63. Abdomen (includes 64, 65).

64. Epigastrium.

65. Belly.

66. Crissum.

E. Tail70. Tail feathers (or rectrices).

72. Upper tail coverts.

73. Lower tail coverts.

F. Wings75. Primary quills.

76. Secondary quills.

77. Bend of wing.

79. False wing (alula).

80. Scapulars.

86. Primary coverts.

89. Secondary coverts (include 92, 93, 94).

92. Greater wing coverts.

93. Lesser wing coverts.

94. Middle wing coverts.

95. Edge of wing.

G. Legs97. Thigh (concealed under skin).

98. Shin (tibia).

103. Heel joint.

103½. Tarsus.

112. Foot.

116. Toes.

126. Outer toe.

127. Inner toe.

128. Middle toe.

129. Hind toe.

For the purpose of defining the form, markings, coloration, and other peculiarities of birds, the different regions of the body have received names by which intelligible reference can be made to any portion. It is, perhaps, hardly necessary to say that all living birds have a head supported on a neck, with jaws extended into a bill covered with a horny sheath, or with skin, the two jaws situated one above the other, and always destitute of teeth. The anterior pair of limbs is developed into wings which, however, are not always capable of use in flight; the posterior serve as legs for the support of the body in an oblique or nearly erect position. The body is covered with feathers of variable structure and character, both in the young bird and the old. (The wings are apparently wanting in some fossil species.)

The following terms, English and Latin, are those most generally employed in describing the external form of birds, and are principally as defined by Illiger. In cases where there is no suitable English word in use, the Latin equivalent only is given. The figure selected for illustration, drawn by Mr. R. Ridgway, is that of the common American robin (Turdus migratorius, L.), and will be familiar to most students of ornithology.

A. Body in General (Corpus)1. Feathers (Plumæ). A dry elastic object, with a central stem at one end forming a hollow horny tube implanted in the skin at its tip, the other feathered on opposite sides.

2. Quills (Pennæ). The large stiff feathers implanted in the posterior edge of the wing and in the tail.

3. Plumage (Ptilosis). The general feathery covering of the body.

4. Unfeathered (Implumis). A portion of skin in which no feathers are inserted.

5. Upper parts (Notæum). The entire upper surface of the animal. (Sometimes restricted to the trunk.)

6. Lower parts (Gastræum). The entire lower surface of the animal. (Sometimes restricted to the trunk.)

7. Anterior portion (Stethiæum). The forward part of the body (about half), both upper and under surfaces, including the chest.

8. Posterior portion (Uræum). The hinder portion of the body (about half), including the abdominal cavity.

B. The Head (Caput)9. Bill (Rostrum). The projecting jaws, one above the other, united by a hinge joint behind, and covered by a horny sheath, or a skin, and enclosing the mouth.