полная версия

полная версияHow the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York

Rows of old women, some smoking stumpy, black clay-pipes, others knitting or idling, all grumbling, sit or stand under the trees that hedge in the almshouse, or limp about in the sunshine, leaning on crutches or bean-pole staffs. They are a “growler-gang” of another sort than may be seen in session on the rocks of the opposite shore at that very moment. They grumble and growl from sunrise to sunset, at the weather, the breakfast, the dinner, the supper; at pork and beans as at corned beef and cabbage; at their Thanksgiving dinner as at the half rations of the sick ward; at the past that had no joy, at the present whose comfort they deny, and at the future without promise. The crusty old men in the next building are not a circumstance to them. The warden, who was in charge of the almshouse for many years, had become so snappish and profane by constant association with a thousand cross old women that I approached him with some misgivings, to request his permission to “take” a group of a hundred or so who were within shot of my camera. He misunderstood me.

“Take them?” he yelled. “Take the thousand of them and be welcome. They will never be still, by –, till they are sent up on Hart’s Island in a box, and I’ll be blamed if I don’t think they will growl then at the style of the funeral.”

And he threw his arms around me in an outburst of enthusiasm over the wondrous good luck that had sent a friend indeed to his door. I felt it to be a painful duty to undeceive him. When I told him that I simply wanted the old women’s picture, he turned away in speechless disgust, and to his dying day, I have no doubt, remembered my call as the day of the champion fool’s visit to the island.

When it is known that many of these old people have been sent to the almshouse to die by their heartless children, for whom they had worked faithfully as long as they were able, their growling and discontent is not hard to understand. Bitter poverty threw them all “on the county,” often on the wrong county at that. Very many of them are old-country poor, sent, there is reason to believe, to America by the authorities to get rid of the obligation to support them. “The almshouse,” wrote a good missionary, “affords a sad illustration of St. Paul’s description of the ‘last days.’ The class from which comes our poorhouse population is to a large extent ‘without natural affection.’” I was reminded by his words of what my friend, the doctor, had said to me a little while before: “Many a mother has told me at her child’s death-bed, ‘I cannot afford to lose it. It costs too much to bury it.’ And when the little one did die there was no time for the mother’s grief. The question crowded on at once, ‘where shall the money come from?’ Natural feelings and affections are smothered in the tenements.” The doctor’s experience furnished a sadly appropriate text for the priest’s sermon.

Pitiful as these are, sights and sounds infinitely more saddening await us beyond the gate that shuts this world of woe off from one whence the light of hope and reason have gone out together. The shuffling of many feet on the macadamized roads heralds the approach of a host of women, hundreds upon hundreds—beyond the turn in the road they still keep coming, marching with the faltering step, the unseeing look and the incessant, senseless chatter that betrays the darkened mind. The lunatic women of the Blackwell’s Island Asylum are taking their afternoon walk. Beyond, on the wide lawn, moves another still stranger procession, a file of women in the asylum dress of dull gray, hitched to a queer little wagon that, with its gaudy adornments, suggests a cross between a baby-carriage and a circus-chariot. One crazy woman is strapped in the seat; forty tug at the rope to which they are securely bound. This is the “chain-gang,” so called once in scoffing ignorance of the humane purpose the contrivance serves. These are the patients afflicted with suicidal mania, who cannot be trusted at large for a moment with the river in sight, yet must have their daily walk as a necessary part of their treatment. So this wagon was invented by a clever doctor to afford them at once exercise and amusement. A merry-go-round in the grounds suggests a variation of this scheme. Ghastly suggestion of mirth, with that stricken host advancing on its aimless journey! As we stop to see it pass, the plaintive strains of a familiar song float through a barred window in the gray stone building. The voice is sweet, but inexpressibly sad: “Oh, how my heart grows weary, far from–” The song breaks off suddenly in a low, troubled laugh. She has forgotten, forgotten–. A woman in the ranks, whose head has been turned toward the window, throws up her hands with a scream. The rest stir uneasily. The nurse is by her side in an instant with words half soothing, half stern. A messenger comes in haste from the asylum to ask us not to stop. Strangers may not linger where the patients pass. It is apt to excite them. As we go in with him the human file is passing yet, quiet restored. The troubled voice of the unseen singer still gropes vainly among the lost memories of the past for the missing key: “Oh! how my heart grows weary, far from–”

“Who is she, doctor?”

“Hopeless case. She will never see home again.”

An average of seventeen hundred women this asylum harbors; the asylum for men up on Ward’s Island even more. Altogether 1,419 patients were admitted to the city asylums for the insane in 1889, and at the end of the year 4,913 remained in them. There is a constant ominous increase in this class of helpless unfortunates that are thrown on the city’s charity. Quite two hundred are added year by year, and the asylums were long since so overcrowded that a great “farm” had to be established on Long Island to receive the surplus. The strain of our hurried, over-worked life has something to do with this. Poverty has more. For these are all of the poor. It is the harvest of sixty and a hundred-fold, the “fearful rolling up and rolling down from generation to generation, through all the ages, of the weakness, vice, and moral darkness of the past.”23 The curse of the island haunts all that come once within its reach. “No man or woman,” says Dr. Louis L. Seaman, who speaks from many years’ experience in a position that gave him full opportunity to observe the facts, “who is ‘sent up’ to these colonies ever returns to the city scot-free. There is a lien, visible or hidden, upon his or her present or future, which too often proves stronger than the best purposes and fairest opportunities of social rehabilitation. The under world holds in rigorous bondage every unfortunate or miscreant who has once ‘served time.’ There is often tragic interest in the struggles of the ensnared wretches to break away from the meshes spun about them. But the maelstrom has no bowels of mercy; and the would-be fugitives are flung back again and again into the devouring whirlpool of crime and poverty, until the end is reached on the dissecting-table, or in the Potter’s Field. What can the moralist or scientist do by way of resuscitation? Very little at best. The flotsam and jetsam are mere shreds and fragments of wasted lives. Such a ministry must begin at the sources—is necessarily prophylactic, nutritive, educational. On these islands there are no flexible twigs, only gnarled, blasted, blighted trunks, insensible to moral or social influences.”

Sad words, but true. The commonest keeper soon learns to pick out almost at sight the “cases” that will leave the penitentiary, the workhouse, the almshouse, only to return again and again, each time more hopeless, to spend their wasted lives in the bondage of the island.

The alcoholic cells in Bellevue Hospital are a way-station for a goodly share of them on their journeys back and forth across the East River. Last year they held altogether 3,694 prisoners, considerably more than one-fourth of the whole number of 13,813 patients that went in through the hospital gates. The daily average of “cases” in this, the hospital of the poor, is over six hundred. The average daily census of all the prisons, hospitals, workhouses, and asylums in the charge of the Department of Charities and Correction last year was about 14,000, and about one employee was required for every ten of this army to keep its machinery running smoothly. The total number admitted in 1889 to all the jails and institutions in the city and on the islands was 138,332. To the almshouse alone 38,600 were admitted; 9,765 were there to start the new year with, and 553 were born with the dark shadow of the poorhouse overhanging their lives, making a total of 48,918. In the care of all their wards the commissioners expended $2,343,372. The appropriation for the police force in 1889 was $4,409,550.94, and for the criminal courts and their machinery $403,190. Thus the first cost of maintaining our standing army of paupers, criminals, and sick poor, by direct taxation, was last year $7,156,112.94.

CHAPTER XXIII.

THE MAN WITH THE KNIFE

A man stood at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Fourteenth Street the other day, looking gloomily at the carriages that rolled by, carrying the wealth and fashion of the avenues to and from the big stores down town. He was poor, and hungry, and ragged. This thought was in his mind: “They behind their well-fed teams have no thought for the morrow; they know hunger only by name, and ride down to spend in an hour’s shopping what would keep me and my little ones from want a whole year.” There rose up before him the picture of those little ones crying for bread around the cold and cheerless hearth—then he sprang into the throng and slashed about him with a knife, blindly seeking to kill, to revenge.

The man was arrested, of course, and locked up. To-day he is probably in a mad-house, forgotten. And the carriages roll by to and from the big stores with their gay throng of shoppers. The world forgets easily, too easily, what it does not like to remember.

Nevertheless the man and his knife had a mission. They spoke in their ignorant, impatient way the warning one of the most conservative, dispassionate of public bodies had sounded only a little while before: “Our only fear is that reform may come in a burst of public indignation destructive to property and to good morals.”24 They represented, one solution of the problem of ignorant poverty versus ignorant wealth that has come down to us unsolved, the danger-cry of which we have lately heard in the shout that never should have been raised on American soil—the shout of “the masses against the classes”—the solution of violence.

There is another solution, that of justice. The choice is between the two. Which shall it be?

“Well!” say some well-meaning people; “we don’t see the need of putting it in that way. We have been down among the tenements, looked them over. There are a good many people there; they are not comfortable, perhaps. What would you have? They are poor. And their houses are not such hovels as we have seen and read of in the slums of the Old World. They are decent in comparison. Why, some of them have brown-stone fronts. You will own at least that they make a decent show.”

Yes! that is true. The worst tenements in New York do not, as a rule, look bad. Neither Hell’s Kitchen, nor Murderers’ Row bears its true character stamped on the front. They are not quite old enough, perhaps. The same is true of their tenants. The New York tough may be ready to kill where his London brother would do little more than scowl; yet, as a general thing he is less repulsively brutal in looks. Here again the reason may be the same: the breed is not so old. A few generations more in the slums, and all that will be changed. To get at the pregnant facts of tenement-house life one must look beneath the surface. Many an apple has a fair skin and a rotten core. There is a much better argument for the tenements in the assurance of the Registrar of Vital Statistics that the death-rate of these houses has of late been brought below the general death-rate of the city, and that it is lowest in the biggest houses. This means two things: one, that the almost exclusive attention given to the tenements by the sanitary authorities in twenty years has borne some fruit, and that the newer tenements are better than the old—there is some hope in that; the other, that the whole strain of tenement-house dwellers has been bred down to the conditions under which it exists, that the struggle with corruption has begotten the power to resist it. This is a familiar law of nature, necessary to its first and strongest impulse of self-preservation. To a certain extent, we are all creatures of the conditions that surround us, physically and morally. But is the knowledge reassuring? In the light of what we have seen, does not the question arise: what sort of creature, then, this of the tenement? I tried to draw his likeness from observation in telling the story of the “tough.” Has it nothing to suggest the man with the knife?

I will go further. I am not willing even to admit it to be an unqualified advantage that our New York tenements have less of the slum look than those of older cities. It helps to delay the recognition of their true character on the part of the well-meaning, but uninstructed, who are always in the majority.

The “dangerous classes” of New York long ago compelled recognition. They are dangerous less because of their own crimes than because of the criminal ignorance of those who are not of their kind. The danger to society comes not from the poverty of the tenements, but from the ill-spent wealth that reared them, that it might earn a usurious interest from a class from which “nothing else was expected.” That was the broad foundation laid down, and the edifice built upon it corresponds to the groundwork. That this is well understood on the “unsafe” side of the line that separates the rich from the poor, much better than by those who have all the advantages of discriminating education, is good cause for disquietude. In it a keen foresight may again dimly discern the shadow of the man with the knife.

Two years ago a great meeting was held at Chickering Hall—I have spoken of it before—a meeting that discussed for days and nights the question how to banish this spectre; how to lay hold with good influences of this enormous mass of more than a million people, who were drifting away faster and faster from the safe moorings of the old faith. Clergymen and laymen from all the Protestant denominations took part in the discussion; nor was a good word forgotten for the brethren of the other great Christian fold who labor among the poor. Much was said that was good and true, and ways were found of reaching the spiritual needs of the tenement population that promise success. But at no time throughout the conference was the real key-note of the situation so boldly struck as has been done by a few far-seeing business men, who had listened to the cry of that Christian builder: “How shall the love of God be understood by those who have been nurtured in sight only of the greed of man?” Their practical programme of “Philanthropy and five per cent.” has set examples in tenement building that show, though they are yet few and scattered, what may in time be accomplished even with such poor, opportunities as New York offers to-day of undoing the old wrong. This is the gospel of justice, the solution that must be sought as the one alternative to the man with the knife.

“Are you not looking too much to the material condition of these people,” said a good minister to me after a lecture in a Harlem church last winter, “and forgetting the inner man?” I told him, “No! for you cannot expect to find an inner man to appeal to in the worst tenement-house surroundings. You must first put the man where he can respect himself. To reverse the argument of the apple: you cannot expect to find a sound core in a rotten fruit.”

CHAPTER XXIV.

WHAT HAS BEEN DONE

In twenty years what has been done in New York to solve the tenement-house problem?

The law has done what it could. That was not always a great deal, seldom more than barely sufficient for the moment. An aroused municipal conscience endowed the Health Department with almost autocratic powers in dealing with this subject, but the desire to educate rather than force the community into a better way dictated their exercise with a slow conservatism that did not always seem wise to the impatient reformer. New York has its St. Antoine, and it has often sadly missed a Napoleon III. to clean up and make light in the dark corners. The obstacles, too, have been many and great. Nevertheless the authorities have not been idle, though it is a grave question whether all the improvements made under the sanitary regulations of recent years deserve the name. Tenements quite as bad as the worst are too numerous yet; but one tremendous factor for evil in the lives of the poor has been taken by the throat, and something has unquestionably been done, where that was possible, to lift those lives out of the rut where they were equally beyond the reach of hope and of ambition. It is no longer lawful to construct barracks to cover the whole of a lot. Air and sunlight have a legal claim, and the day of rear tenements is past. Two years ago a hundred thousand people burrowed in these inhuman dens; but some have been torn down since. Their number will decrease steadily until they shall have become a bad tradition of a heedless past. The dark, unventilated bedroom is going with them, and the open sewer. The day is at hand when the greatest of all evils that now curse life in the tenements—the dearth of water in the hot summer days—will also have been remedied, and a long step taken toward the moral and physical redemption of their tenants.

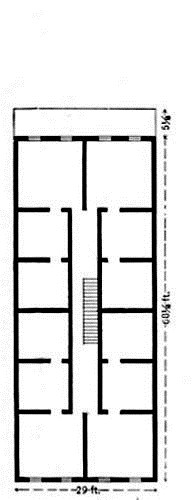

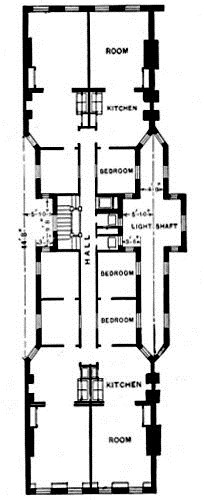

Old Style Tenement.

Single Lot Tenement of To-day.

EVOLUTION OF THE TENEMENT IN TWENTY YEARS.

Public sentiment has done something also, but very far from enough. As a rule, it has slumbered peacefully until some flagrant outrage on decency and the health of the community aroused it to noisy but ephemeral indignation, or until a dreaded epidemic knocked at our door. It is this unsteadiness of purpose that has been to a large extent responsible for the apparent lagging of the authorities in cases not involving immediate danger to the general health. The law needs a much stronger and readier backing of a thoroughly enlightened public sentiment to make it as effective as it might be made. It is to be remembered that the health officers, in dealing with this subject of dangerous houses, are constantly trenching upon what each landlord considers his private rights, for which he is ready and bound to fight to the last. Nothing short of the strongest pressure will avail to convince him that these individual rights are to be surrendered for the clear benefit of the whole. It is easy enough to convince a man that he ought not to harbor the thief who steals people’s property; but to make him see that he has no right to slowly kill his neighbors, or his tenants, by making a death-trap of his house, seems to be the hardest of all tasks. It is apparently the slowness of the process that obscures his mental sight. The man who will fight an order to repair the plumbing in his house through every court he can reach, would suffer tortures rather than shed the blood of a fellow-man by actual violence. Clearly, it is a matter of education on the part of the landlord no less than the tenant.

In spite of this, the landlord has done his share; chiefly perhaps by yielding—not always gracefully—when it was no longer of any use to fight. There have been exceptions, however: men and women who have mended and built with an eye to the real welfare of their tenants as well as to their own pockets. Let it be well understood that the two are inseparable, if any good is to come of it. The business of housing the poor, if it is to amount to anything, must be business, as it was business with our fathers to put them where they are. As charity, pastime, or fad, it will miserably fail, always and everywhere. This is an inexorable rule, now thoroughly well understood in England and continental Europe, and by all who have given the matter serious thought here. Call it poetic justice, or divine justice, or anything else, it is a hard fact, not to be gotten over. Upon any other plan than the assumption that the workman has a just claim to a decent home, and the right to demand it, any scheme for his relief fails. It must be a fair exchange of the man’s money for what he can afford to buy at a reasonable price. Any charity scheme merely turns him into a pauper, however it may be disguised, and drowns him hopelessly in the mire out of which it proposed to pull him. And this principle must pervade the whole plan. Expert management of model tenements succeeds where amateur management, with the best intentions, gives up the task, discouraged, as a flat failure. Some of the best-conceived enterprises, backed by abundant capital and good-will, have been wrecked on this rock. Sentiment, having prompted the effort, forgot to stand aside and let business make it.

Business, in a wider sense, has done more than all other agencies together to wipe out the worst tenements. It has been New York’s real Napoleon III., from whose decree there was no appeal. In ten years I have seen plague-spots disappear before its onward march, with which health officers, police, and sanitary science had struggled vainly since such struggling began as a serious business. And the process goes on still. Unfortunately, the crowding in some of the most densely packed quarters down town has made the property there so valuable, that relief from this source is less confidently to be expected, at all events in the near future. Still, their time may come also. It comes so quickly sometimes as to fairly take one’s breath away. More than once I have returned, after a few brief weeks, to some specimen rookery in which I was interested, to find it gone and an army of workmen delving twenty feet underground to lay the foundation of a mighty warehouse. That was the case with the “Big Flat” in Mott Street. I had not had occasion to visit it for several months last winter, and when I went there, entirely unprepared for a change, I could not find it. It had always been conspicuous enough in the landscape before, and I marvelled much at my own stupidity until, by examining the number of the house, I found out that I had gone right. It was the “flat” that had disappeared. In its place towered a six-story carriage factory with business going on on every floor, as if it had been there for years and years.

This same “Big Flat” furnished a good illustration of why some well-meant efforts in tenement building have failed. Like Gotham Court, it was originally built as a model tenement, but speedily came to rival the Court in foulness. It became a regular hot-bed of thieves and peace-breakers, and made no end of trouble for the police. The immediate reason, outside of the lack of proper supervision, was that it had open access to two streets in a neighborhood where thieves and “toughs” abounded. These took advantage of an arrangement that had been supposed by the builders to be a real advantage as a means of ventilation, and their occupancy drove honest folk away. Murderers’ Alley, of which I have spoken elsewhere, and the sanitary inspector’s experiment with building a brick wall athwart it to shut off travel through the block, is a parallel case.

The causes that operate to obstruct efforts to better the lot of the tenement population are, in our day, largely found among the tenants themselves. This is true particularly of the poorest. They are shiftless, destructive, and stupid; in a word, they are what the tenements have made them. It is a dreary old truth that those who would fight for the poor must fight the poor to do it. It must be confessed that there is little enough in their past experience to inspire confidence in the sincerity of the effort to help them. I recall the discomfiture of a certain well-known philanthropist, since deceased, whose heart beat responsive to other suffering than that of human kind. He was a large owner of tenement property, and once undertook to fit out his houses with stationary tubs, sanitary plumbing, wood-closets, and all the latest improvements. He introduced his rough tenants to all this magnificence without taking the precaution of providing a competent housekeeper, to see that the new acquaintances got on together. He felt that his tenants ought to be grateful for the interest he took in them. They were. They found the boards in the wood-closets fine kindling wood, while the pipes and faucets were as good as cash at the junk shop. In three months the owner had to remove what was left of his improvements. The pipes were cut and the houses running full of water, the stationary tubs were put to all sorts of uses except washing, and of the wood-closets not a trace was left. The philanthropist was ever after a firm believer in the total depravity of tenement-house people. Others have been led to like reasoning by as plausible arguments, without discovering that the shiftlessness and ignorance that offended them were the consistent crop of the tenement they were trying to reform, and had to be included in the effort. The owners of a block of model tenements uptown had got their tenants comfortably settled, and were indulging in high hopes of their redemption under proper management, when a contractor ran up a row of “skin” tenements, shaky but fair to look at, with brown-stone trimmings and gewgaws. The result was to tempt a lot of the well-housed tenants away. It was a very astonishing instance of perversity to the planners of the benevolent scheme; but, after all, there was nothing strange in it. It is all a matter of education, as I said about the landlord.