полная версия

полная версияHow the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York

It is not always that their little diversions end as harmlessly as did this, even from the standpoint of the Jew, who was pretty badly hurt. Not far from the preserves of the Montgomery Guards, in Poverty Gap, directly opposite the scene of the murder to which I have referred in a note explaining the picture of the Cunningham family (p. 169), a young lad, who was the only support of his aged parents, was beaten to death within a few months by the “Alley Gang,” for the same offence that drew down the displeasure of its neighbors upon the pedlar: that of being at work trying to earn an honest living. I found a part of the gang asleep the next morning, before young Healey’s death was known, in a heap of straw on the floor of an unoccupied room in the same row of rear tenements in which the murdered boy’s home was. One of the tenants, who secretly directed me to their lair, assuring me that no worse scoundrels went unhung, ten minutes later gave the gang, to its face, an official character for sobriety and inoffensiveness that very nearly startled me into an unguarded rebuke of his duplicity. I caught his eye in time and held my peace. The man was simply trying to protect his own home, while giving such aid as he safely could toward bringing the murderous ruffians to justice. The incident shows to what extent a neighborhood may be terrorized by a determined gang of these reckless toughs.

In Poverty Gap there were still a few decent people left. When it comes to Hell’s Kitchen, or to its compeers at the other end of Thirty-ninth Street over by the East River, and further down First Avenue in “the Village,” the Rag Gang and its allies have no need of fearing treachery in their periodical battles with the police. The entire neighborhood takes a hand on these occasions, the women in the front rank, partly from sheer love of the “fun,” but chiefly because husbands, brothers, and sweet-hearts are in the fight to a man and need their help. Chimney-tops form the staple of ammunition then, and stacks of loose brick and paving-stones, carefully hoarded in upper rooms as a prudent provision against emergencies. Regular patrol posts are established by the police on the housetops in times of trouble in these localities, but even then they do not escape whole-skinned, if, indeed, with their lives; neither does the gang. The policeman knows of but one cure for the tough, the club, and he lays it on without stint whenever and wherever he has the chance, knowing right well that, if caught at a disadvantage, he will get his outlay back with interest. Words are worse than wasted in the gang-districts. It is a blow at sight, and the tough thus accosted never stops to ask questions. Unless he is “wanted” for some signal outrage, the policeman rarely bothers with arresting him. He can point out half a dozen at sight against whom indictments are pending by the basketful, but whom no jail ever held many hours. They only serve to make him more reckless, for he knows that the political backing that has saved him in the past can do it again. It is a commodity that is only exchangeable “for value received,” and it is not hard to imagine what sort of value is in demand. The saloon, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, stands behind the bargain.

For these reasons, as well as because he knows from frequent experience his own way to be the best, the policeman lets the gangs alone except when they come within reach of his long night-stick. They have their “club-rooms” where they meet, generally in a tenement, sometimes under a pier or a dump, to carouse, play cards, and plan their raids; their “fences,” who dispose of the stolen property. When the necessity presents itself for a descent upon the gang after some particularly flagrant outrage, the police have a task on hand that is not of the easiest. The gangs, like foxes, have more than one hole to their dens. In some localities, where the interior of a block is filled with rear tenements, often set at all sorts of odd angles, surprise alone is practicable. Pursuit through the winding ways and passages is impossible. The young thieves know them all by heart. They have their runways over roofs and fences which no one else could find. Their lair is generally selected with special reference to its possibilities of escape. Once pitched upon, its occupation by the gang, with its ear-mark of nightly symposiums, “can-rackets” in the slang of the street, is the signal for a rapid deterioration of the tenement, if that is possible. Relief is only to be had by ousting the intruders. An instance came under my notice in which valuable property had been well-nigh ruined by being made the thoroughfare of thieves by night and by day. They had chosen it because of a passage that led through the block by way of several connecting halls and yards. The place came soon to be known as “Murderers Alley.” Complaint was made to the Board of Health, as a last resort, of the condition of the property. The practical inspector who was sent to report upon it suggested to the owner that he build a brick-wall in a place where it would shut off communication between the streets, and he took the advice. Within the brief space of a few months the house changed character entirely, and became as decent as it had been before the convenient runway was discovered.

TYPICAL TOUGHS (FROM THE ROGUES’ GALLERY).

This was in the Sixth Ward, where the infamous Whyo Gang until a few years ago absorbed the worst depravity of the Bend and what is left of the Five Points. The gang was finally broken up when its leader was hanged for murder after a life of uninterrupted and unavenged crimes, the recital of which made his father confessor turn pale, listening in the shadow of the scaffold, though many years of labor as chaplain of the Tombs had hardened him to such rehearsals. The great Whyo had been a “power in the ward,” handy at carrying elections for the party or faction that happened to stand in need of his services and was willing to pay for them in money or in kind. Other gangs have sprung up since with as high ambition and a fair prospect of outdoing their predecessor. The conditions that bred it still exist, practically unchanged. Inspector Byrnes is authority for the statement that throughout the city the young tough has more “ability” and “nerve” than the thief whose example he successfully emulates. He begins earlier, too. Speaking of the increase of the native element among criminal prisoners exhibited in the census returns of the last thirty years,21 the Rev. Fred. H. Wines says, “their youth is a very striking fact.” Had he confined his observations to the police courts of New York, he might have emphasized that remark and found an explanation of the discovery that “the ratio of prisoners in cities is two and one-quarter times as great as in the country at large,” a computation that takes no account of the reformatories for juvenile delinquents, or the exhibit would have been still more striking. Of the 82,200 persons arrested by the police in 1889, 10,505 were under twenty years old. The last report of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children enumerates, as “a few typical cases,” eighteen “professional cracksmen,” between nine and fifteen years old, who had been caught with burglars’ tools, or in the act of robbery. Four of them, hardly yet in long trousers, had “held up” a wayfarer in the public street and robbed him of $73. One, aged sixteen, “was the leader of a noted gang of young robbers in Forty-ninth Street. He committed murder, for which he is now serving a term of nineteen years in State’s Prison.” Four of the eighteen were girls and quite as bad as the worst. In a few years they would have been living with the toughs of their choice without the ceremony of a marriage, egging them on by their pride in their lawless achievements, and fighting side by side with them in their encounters with the “cops.”

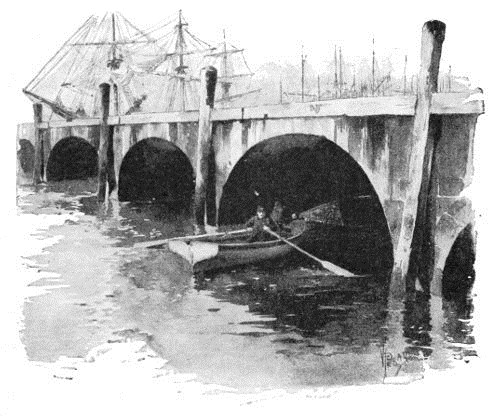

The exploits of the Paradise Park Gang in the way of highway robbery showed last summer that the embers of the scattered Whyo Gang, upon the wreck of which it grew, were smouldering still. The hanging of Driscoll broke up the Whyos because they were a comparatively small band, and, with the incomparable master-spirit gone, were unable to resist the angry rush of public indignation that followed the crowning outrage. This is the history of the passing away of famous gangs from time to time. The passing is more apparent than real, however. Some other daring leader gathers the scattered elements about him soon, and the war on society is resumed. A bare enumeration of the names of the best-known gangs would occupy pages of this book. The Rock Gang, the Rag Gang, the Stable Gang, and the Short Tail Gang down about the “Hook” have all achieved bad eminence, along with scores of others that have not paraded so frequently in the newspapers. By day they loaf in the corner-groggeries on their beat, at night they plunder the stores along the avenues, or lie in wait at the river for unsteady feet straying their way. The man who is sober and minds his own business they seldom molest, unless he be a stranger inquiring his way, or a policeman and the gang twenty against the one. The tipsy wayfarer is their chosen victim, and they seldom have to look for him long. One has not far to go to the river from any point in New York. The man who does not know where he is going is sure to reach it sooner or later. Should he foolishly resist or make an outcry—dead men tell no tales. “Floaters” come ashore every now and then with pockets turned inside out, not always evidence of a post-mortem inspection by dock-rats. Police patrol the rivers as well as the shore on constant look-out for these, but seldom catch up with them. If overtaken after a race during which shots are often exchanged from the boats, the thieves have an easy way of escaping and at the same time destroying the evidence against them; they simply upset the boat. They swim, one and all, like real rats; the lost plunder can be recovered at leisure the next day by diving or grappling. The loss of the boat counts for little. Another is stolen, and the gang is ready for business again.

HUNTING RIVER THIEVES.

The fiction of a social “club,” which most of the gangs keep up, helps them to a pretext for blackmailing the politicians and the storekeepers in their bailiwick at the annual seasons of their picnic, or ball. The “thieves’ ball” is as well known and recognized an institution on the East Side as the Charity Ball in a different social stratum, although it does not go by that name, in print at least. Indeed, the last thing a New York tough will admit is that he is a thief. He dignifies his calling with the pretence of gambling. He does not steal: he “wins” your money or your watch, and on the police returns he is a “speculator.” If, when he passes around the hat for “voluntary” contributions, any storekeeper should have the temerity to refuse to chip in, he may look for a visit from the gang on the first dark night, and account himself lucky if his place escapes being altogether wrecked. The Hell’s Kitchen Gang and the Rag Gang have both distinguished themselves within recent times by blowing up objectionable stores with stolen gunpowder. But if no such episode mar the celebration, the excursion comes off and is the occasion for a series of drunken fights that as likely as not end in murder. No season has passed within my memory that has not seen the police reserves called out to receive some howling pandemonium returning from a picnic grove on the Hudson or on the Sound. At least one peaceful community up the river, that had borne with this nuisance until patience had ceased to be a virtue, received a boat-load of such picnickers in a style befitting the occasion and the cargo. The outraged citizens planted a howitzer on the dock, and bade the party land at their peril. With the loaded gun pointed dead at them, the furious toughs gave up and the peace was not broken on the Hudson that day, at least not ashore. It is good cause for congratulation that the worst of all forms of recreation popular among the city’s toughs, the moonlight picnic, has been effectually discouraged. Its opportunities for disgraceful revelry and immorality were unrivalled anywhere.

In spite of influence and protection, the tough reaches eventually the end of his rope. Occasionally—not too often—there is a noose on it. If not, the world that owes him a living, according to his creed, will insist on his earning it on the safe side of a prison wall. A few, a very few, have been clubbed into an approach to righteousness from the police standpoint. The condemned tough goes up to serve his “bit” or couple of “stretches,” followed by the applause of his gang. In the prison he meets older thieves than himself, and sits at their feet listening with respectful admiration to their accounts of the great doings that sent them before. He returns with the brand of the jail upon him, to encounter the hero-worship of his old associates as an offset to the cold shoulder given him by all the rest of the world. Even if he is willing to work, disgusted with the restraint and hard labor of prison life, and in a majority of cases that thought is probably uppermost in his mind, no one will have him around. If, with the assistance of Inspector Byrnes, who is a philanthropist in his own practical way, he secures a job, he is discharged on the slightest provocation, and for the most trifling fault. Very soon he sinks back into his old surroundings, to rise no more until he is lost to view in the queer, mysterious way in which thieves and fallen women disappear. No one can tell how. In the ranks of criminals he never rises above that of the “laborer,” the small thief or burglar, or general crook, who blindly does the work planned for him by others, and runs the biggest risk for the poorest pay. It cannot be said that the “growler” brought him luck, or its friendship fortune. And yet, if his misdeeds have helped to make manifest that all effort to reclaim his kind must begin with the conditions of life against which his very existence is a protest, even the tough has not lived in vain. This measure of credit at least should be accorded him, that, with or without his good-will, he has been a factor in urging on the battle against the slums that bred him. It is a fight in which eternal vigilance is truly the price of liberty and the preservation of society.

CHAPTER XX.

THE WORKING GIRLS OF NEW YORK

Of the harvest of tares, sown in iniquity and reaped in wrath, the police returns tell the story. The pen that wrote the “Song of the Shirt” is needed to tell of the sad and toil-worn lives of New York’s working-women. The cry echoes by night and by day through its tenements:

Oh, God! that bread should be so dear,And flesh and blood so cheap!Six months have not passed since at a great public meeting in this city, the Working Women’s Society reported: “It is a known fact that men’s wages cannot fall below a limit upon which they can exist, but woman’s wages have no limit, since the paths of shame are always open to her. It is simply impossible for any woman to live without assistance on the low salary a saleswoman earns, without depriving herself of real necessities.... It is inevitable that they must in many instances resort to evil.” It was only a few brief weeks before that verdict was uttered, that the community was shocked by the story of a gentle and refined woman who, left in direst poverty to earn her own living alone among strangers, threw herself from her attic window, preferring death to dishonor. “I would have done any honest work, even to scrubbing,” she wrote, drenched and starving, after a vain search for work in a driving storm. She had tramped the streets for weeks on her weary errand, and the only living wages that were offered her were the wages of sin. The ink was not dry upon her letter before a woman in an East Side tenement wrote down her reason for self-murder: “Weakness, sleeplessness, and yet obliged to work. My strength fails me. Sing at my coffin: ‘Where does the soul find a home and rest?’” Her story may be found as one of two typical “cases of despair” in one little church community, in the City Mission Society’s Monthly for last February. It is a story that has many parallels in the experience of every missionary, every police reporter and every family doctor whose practice is among the poor.

It is estimated that at least one hundred and fifty thousand women and girls earn their own living in New York; but there is reason to believe that this estimate falls far short of the truth when sufficient account is taken of the large number who are not wholly dependent upon their own labor, while contributing by it to the family’s earnings. These alone constitute a large class of the women wage-earners, and it is characteristic of the situation that the very fact that some need not starve on their wages condemns the rest to that fate. The pay they are willing to accept all have to take. What the “everlasting law of supply and demand,” that serves as such a convenient gag for public indignation, has to do with it, one learns from observation all along the road of inquiry into these real woman’s wrongs. To take the case of the saleswomen for illustration: The investigation of the Working Women’s Society disclosed the fact that wages averaging from $2 to $4.50 a week were reduced by excessive fines, the employers placing a value upon time lost that is not given to services rendered." A little girl, who received two dollars a week, made cash-sales amounting to $167 in a single day, while the receipts of a fifteen-dollar male clerk in the same department footed up only $125; yet for some trivial mistake the girl was fined sixty cents out of her two dollars. The practice prevailed in some stores of dividing the fines between the superintendent and the time-keeper at the end of the year. In one instance they amounted to $3,000, and “the superintendent was heard to charge the time-keeper with not being strict enough in his duties.” One of the causes for fine in a certain large store was sitting down. The law requiring seats for saleswomen, generally ignored, was obeyed faithfully in this establishment. The seats were there, but the girls were fined when found using them.

Cash-girls receiving $1.75 a week for work that at certain seasons lengthened their day to sixteen hours were sometimes required to pay for their aprons. A common cause for discharge from stores in which, on account of the oppressive heat and lack of ventilation, “girls fainted day after day and came out looking like corpses,” was too long service. No other fault was found with the discharged saleswomen than that they had been long enough in the employ of the firm to justly expect an increase of salary. The reason was even given with brutal frankness, in some instances.

These facts give a slight idea of the hardships and the poor pay of a business that notoriously absorbs child-labor. The girls are sent to the store before they have fairly entered their teens, because the money they can earn there is needed for the support of the family. If the boys will not work, if the street tempts them from home, among the girls at least there must be no drones. To keep their places they are told to lie about their age and to say that they are over fourteen. The precaution is usually superfluous. The Women’s Investigating Committee found the majority of the children employed in the stores to be under age, but heard only in a single instance of the truant officers calling. In that case they came once a year and sent the youngest children home; but in a month’s time they were all back in their places, and were not again disturbed. When it comes to the factories, where hard bodily labor is added to long hours, stifling rooms, and starvation wages, matters are even worse. The Legislature has passed laws to prevent the employment of children, as it has forbidden saloon-keepers to sell them beer, and it has provided means of enforcing its mandate, so efficient, that the very number of factories in New York is guessed at as in the neighborhood of twelve thousand. Up till this summer, a single inspector was charged with the duty of keeping the run of them all, and of seeing to it that the law was respected by the owners.

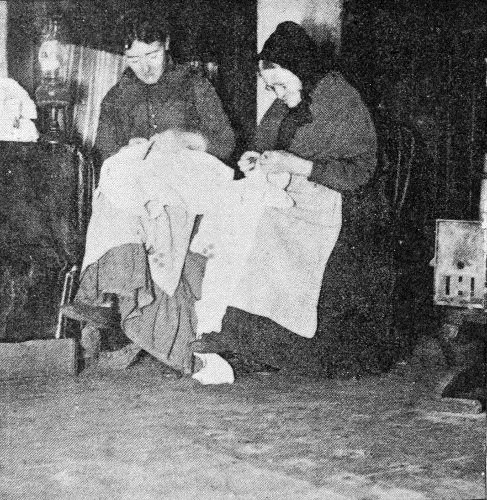

SEWING AND STARVING IN AN ELIZABETH STREET ATTIC.

Sixty cents is put as the average day’s earnings of the 150,000, but into this computation enters the stylish “cashier’s” two dollars a day, as well as the thirty cents of the poor little girl who pulls threads in an East Side factory, and, if anything, the average is probably too high. Such as it is, however, it represents board, rent, clothing, and “pleasure” to this army of workers. Here is the case of a woman employed in the manufacturing department of a Broadway house. It stands for a hundred like her own. She averages three dollars a week. Pays $1.50 for her room; for breakfast she has a cup of coffee; lunch she cannot afford. One meal a day is her allowance. This woman is young, she is pretty. She has “the world before her.” Is it anything less than a miracle if she is guilty of nothing worse than the “early and improvident marriage,” against which moralists exclaim as one of the prolific causes of the distress of the poor? Almost any door might seem to offer welcome escape from such slavery as this. “I feel so much healthier since I got three square meals a day,” said a lodger in one of the Girls’ Homes. Two young sewing-girls came in seeking domestic service, so that they might get enough to eat. They had been only half-fed for some time, and starvation had driven them to the one door at which the pride of the American-born girl will not permit her to knock, though poverty be the price of her independence.

The tenement and the competition of public institutions and farmers’ wives and daughters, have done the tyrant shirt to death, but they have not bettered the lot of the needle-women. The sweater of the East Side has appropriated the flannel shirt. He turns them out to-day at forty-five cents a dozen, paying his Jewish workers from twenty to thirty-five cents. One of these testified before the State Board of Arbitration, during the shirtmakers’ strike, that she worked eleven hours in the shop and four at home, and had never in the best of times made over six dollars a week. Another stated that she worked from 4 o’clock in the morning to 11 at night. These girls had to find their own thread and pay for their own machines out of their wages. The white shirt has gone to the public and private institutions that shelter large numbers of young girls, and to the country. There are not half as many shirtmakers in New York to-day as only a few years ago, and some of the largest firms have closed their city shops. The same is true of the manufacturers of underwear. One large Broadway firm has nearly all its work done by farmers’ girls in Maine, who think themselves well off if they can earn two or three dollars a week to pay for a Sunday silk, or the wedding outfit, little dreaming of the part they are playing in starving their city sisters. Literally, they sew “with double thread, a shroud as well as a shirt.” Their pin-money sets the rate of wages for thousands of poor sewing-girls in New York. The average earnings of the worker on underwear to-day do not exceed the three dollars which her competitor among the Eastern hills is willing to accept as the price of her play. The shirtmaker’s pay is better only because the very finest custom work is all there is left for her to do.

Calico wrappers at a dollar and a half a dozen—the very expert sewers able to make from eight to ten, the common run five or six—neckties at from 25 to 75 cents a dozen, with a dozen as a good day’s work, are specimens of women’s wages. And yet people persist in wondering at the poor quality of work done in the tenements! Italian cheap labor has come of late also to possess this poor field, with the sweater in its train. There is scarce a branch of woman’s work outside of the home in which wages, long since at low-water mark, have not fallen to the point of actual starvation. A case was brought to my notice recently by a woman doctor, whose heart as well as her life-work is with the poor, of a widow with two little children she found at work in an East Side attic, making paper-bags. Her father, she told the doctor, had made good wages at it; but she received only five cents for six hundred of the little three-cornered bags, and her fingers had to be very swift and handle the paste-brush very deftly to bring her earnings up to twenty-five and thirty cents a day. She paid four dollars a month for her room. The rest went to buy food for herself and the children. The physician’s purse, rather than her skill, had healing for their complaint.