полная версия

полная версияHow the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York

The Improved Dwellings Association put up its block of thirteen houses in East Seventy-second Street nine years ago. Their cost, estimated at about $240,000 with the land, was increased to $285,000 by troubles with the contractor engaged to build them. Thus the Association’s task did not begin under the happiest auspices. Unexpected expenses came to deplete its treasury. The neighborhood was new and not crowded at the start. No expense was spared, and the benefit of all the best and most recent experience in tenement building was given to the tenants. The families were provided with from two to four rooms, all “outer” rooms, of course, at rents ranging from $14 per month for the four on the ground floor, to $6.25 for two rooms on the top floor. Coal lifts, ash-chutes, common laundries in the basement, and free baths, are features of these buildings that were then new enough to be looked upon with suspicion by the doubting Thomases who predicted disaster. There are rooms in the block for 218 families, and when I looked in recently all but nine of the apartments were let. One of the nine was rented while I was in the building. The superintendent told me that he had little trouble with disorderly tenants, though the buildings shelter all sorts of people. Mr. W. Bayard Cutting, the President of the Association, writes to me:

“By the terms of subscription to the stock before incorporation, dividends were limited to five per cent. on the stock of the Improved Dwellings Association. These dividends have been paid (two per cent. each six months) ever since the expiration of the first six months of the buildings operation. All surplus has been expended upon the buildings. New and expensive roofs have been put on for the comfort of such tenants as might choose to use them. The buildings have been completely painted inside and out in a manner not contemplated at the outset. An expensive set of fire-escapes has been put on at the command of the Fire Department, and a considerable number of other improvements made. I regard the experiment as eminently successful and satisfactory, particularly when it is considered that the buildings were the first erected in this city upon anything like a large scale, where it was proposed to meet the architectural difficulties that present themselves in the tenement-house problem. I have no doubt that the experiment could be tried to-day with the improved knowledge which has come with time, and a much larger return be shown upon the investment. The results referred to have been attained in spite of the provision which prevents the selling of liquor upon the Association’s premises. You are aware, of course, how much larger rent can be obtained for a liquor saloon than for an ordinary store. An investment at five per cent. net upon real estate security worth more than the principal sum, ought to be considered desirable.”

The Tenement House Building Company made its “experiment” in a much more difficult neighborhood, Cherry Street, some six years later. Its houses shelter many Russian Jews, and the difficulty of keeping them in order is correspondingly increased, particularly as there are no ash-chutes in the houses. It has been necessary even to shut the children out of the yards upon which the kitchen windows give, lest they be struck by something thrown out by the tenants, and killed. It is the Cherry Street style, not easily got rid of. Nevertheless, the houses are well kept. Of the one hundred and six “apartments,” only four were vacant in August. Professor Edwin R. A. Seligman, the secretary of the company, writes to me: “The tenements are now a decided success.” In the three years since they were built, they have returned an interest of from five to five and a half per cent. on the capital invested. The original intention of making the tenants profit-sharers on a plan of rent insurance, under which all earnings above four per cent. would be put to the credit of the tenants, has not yet been carried out.

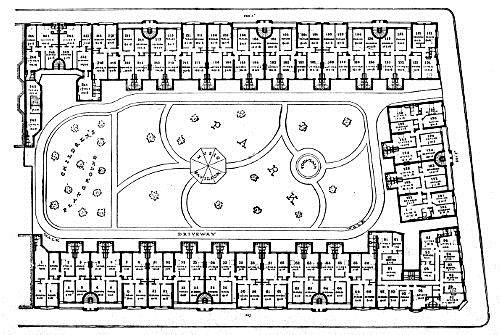

GENERAL PLAN OF THE RIVERSIDE BUILDINGS (A. T. WHITE’S) IN BROOKLYN.

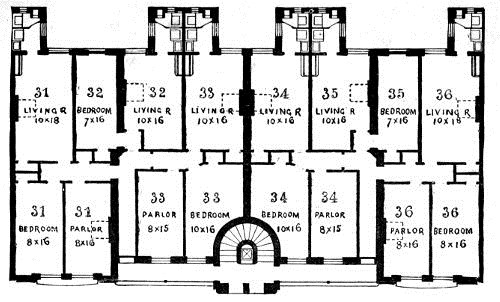

FLOOR PLAN OF ONE DIVISION IN THE RIVERSIDE BUILDINGS, SHOWING SIX “APARTMENTS.”

A scheme of dividends to tenants on a somewhat similar plan has been carried out by a Brooklyn builder, Mr. A. T. White, who has devoted a life of beneficent activity to tenement building, and whose experience, though it has been altogether across the East River, I regard asjustly applying to New York as well. He so regards it himself. Discussing the cost of building, he says: “There is not the slightest reason to doubt that the financial result of a similar undertaking in any tenement-house district of New York City would be equally good.... High cost of land is no detriment, provided the value is made by the pressure of people seeking residence there. Rents in New York City bear a higher ratio to Brooklyn rents than would the cost of land and building in the one city to that in the other.” The assertion that Brooklyn furnishes a better class of tenants than the tenement districts in New York would not be worth discussing seriously, even if Mr. White did not meet it himself with the statement that the proportion of day-laborers and sewing-women in his houses is greater than in any of the London model tenements, showing that they reach the humblest classes.

Mr. White has built homes for five hundred poor families since he began his work, and has made it pay well enough to allow good tenants a share in the profits, averaging nearly one month’s rent out of the twelve, as a premium upon promptness and order. The plan of his last tenements, reproduced on p. 292, may be justly regarded as the beau ideal of the model tenement for a great city like New York. It embodies all the good features of Sir Sydney Waterlow’s London plan, with improvements suggested by the builder’s own experience. Its chief merit is that it gathers three hundred real homes, not simply three hundred families, under one roof. Three tenants, it will be seen, everywhere live together. Of the rest of the three hundred they may never know, rarely see, one. Each has his private front-door. The common hall, with all that it stands for, has disappeared. The fire-proof stairs are outside the house, a perfect fire-escape. Each tenant has his own scullery and ash-flue. There are no air-shafts, for they are not needed. Every room, under the admirable arrangement of the plan, looks out either upon the street or the yard, that is nothing less than a great park with a play-ground set apart for the children, where they may dig in the sand to their heart’s content. Weekly concerts are given in the park by a brass band. The drying of clothes is done on the roof, where racks are fitted up for the purpose. The outside stairways end in turrets that give the buildings a very smart appearance. Mr. White never has any trouble with his tenants, though he gathers in the poorest; nor do his tenements have anything of the “institution character” that occasionally attaches to ventures of this sort, to their damage. They are like a big village of contented people, who live in peace with one another because they have elbow-room even under one big roof.

Enough has been said to show that model tenements can be built successfully and made to pay in New York, if the owner will be content with the five or six per cent. he does not even dream of when investing his funds in “governments” at three or four. It is true that in the latter case he has only to cut off his coupons and cash them. But the extra trouble of looking after his tenement property, that is the condition of his highest and lasting success, is the penalty exacted for the sins of our fathers that “shall be visited upon the children, unto the third and fourth generation.” We shall indeed be well off, if it stop there. I fear there is too much reason to believe that our own iniquities must be added to transmit the curse still further. And yet, such is the leavening influence of a good deed in that dreary desert of sin and suffering, that the erection of a single good tenement has the power to change, gradually but surely, the character of a whole bad block. It sets up a standard to which the neighborhood must rise, if it cannot succeed in dragging it down to its own low level.

And so this task, too, has come to an end. Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap. I have aimed to tell the truth as I saw it. If this book shall have borne ever so feeble a hand in garnering a harvest of justice, it has served its purpose. While I was writing these lines I went down to the sea, where thousands from the city were enjoying their summer rest. The ocean slumbered under a cloudless sky. Gentle waves washed lazily over the white sand, where children fled before them with screams of laughter. Standing there and watching their play, I was told that during the fierce storms of winter it happened that this sea, now so calm, rose in rage and beat down, broke over the bluff, sweeping all before it. No barrier built by human hands had power to stay it then. The sea of a mighty population, held in galling fetters, heaves uneasily in the tenements. Once already our city, to which have come the duties and responsibilities of metropolitan greatness before it was able to fairly measure its task, has felt the swell of its resistless flood. If it rise once more, no human power may avail to check it. The gap between the classes in which it surges, unseen, unsuspected by the thoughtless, is widening day by day. No tardy enactment of law, no political expedient, can close it. Against all other dangers our system of government may offer defence and shelter; against this not. I know of but one bridge that will carry us over safe, a bridge founded upon justice and built of human hearts. I believe that the danger of such conditions as are fast growing up around us is greater for the very freedom which they mock. The words of the poet, with whose lines I prefaced this book, are truer to-day, have far deeper meaning to us, than when they were penned forty years ago:

“—Think ye that building shall endureWhich shelters the noble and crushes the poor?”APPENDIX.

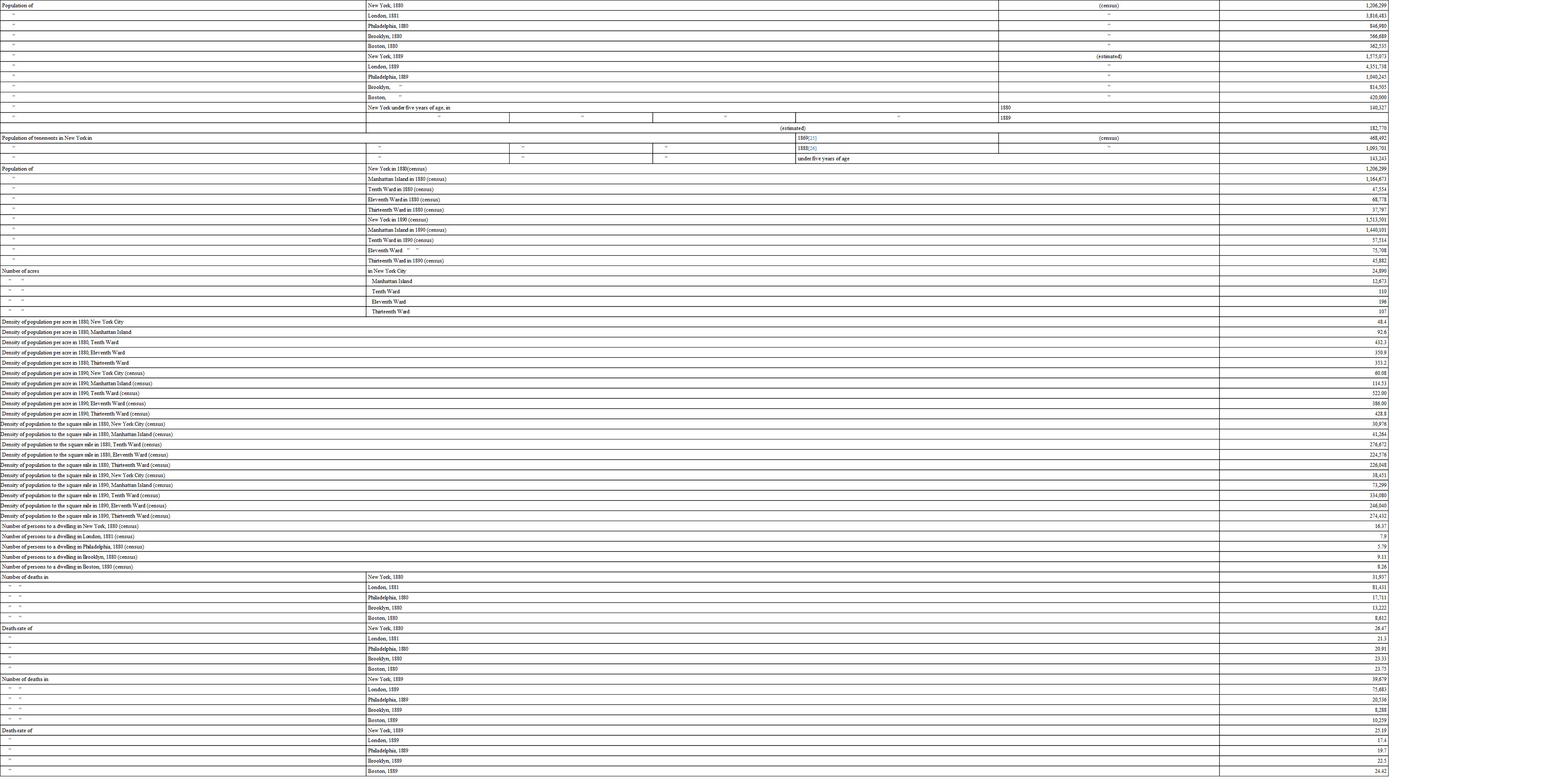

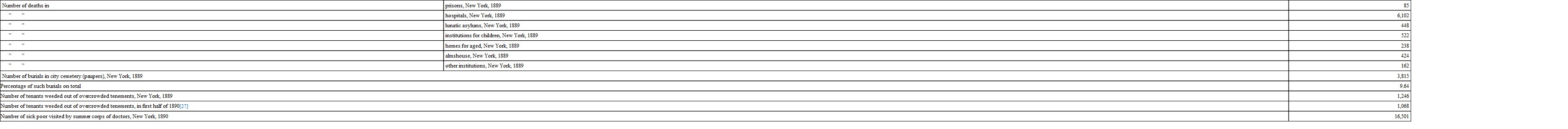

STATISTICS BEARING ON THE TENEMENT PROBLEM

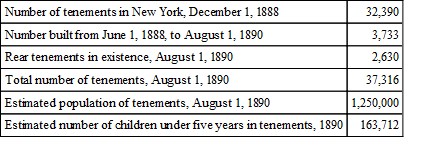

Statistics of population were left out of the text in the hope that the results of this year’s census would be available as a basis for calculation before the book went to press. They are now at hand, but their correctness is disputed. The statisticians of the Health Department claim that New York’s population has been underestimated a hundred thousand at least, and they appear to have the best of the argument. A re-count is called for, and the printer will not wait. Such statistics as follow have been based on the Health Department estimates, except where the census source is given. The extent of the quarrel of official figures may be judged from this one fact, that the ordinarily conservative and careful calculations of the Sanitary Bureau make the death-rate of New York, in 1889, 25.19 for the thousand of a population of 1,575,073, while the census would make it 26.76 in a population of 1,482,273.

25 In 1869, a tenement was a house occupied by four families or more

26 In 1888, a tenement was a house occupied by three families or more

For every person who dies there are always two disabled by illness, so that there was a regular average of 79,358 New Yorkers on the sick-list at any moment last year. It is usual to count 28 cases of sickness the year round for every death, and this would give a total for the year 1889 of 1,111,082 of illness of all sorts.

This is exclusive of deaths in institutions, properly referable to the tenements in most cases. The adult death-rate is found to decrease in the larger tenements of newer construction. The child mortality increases, reaching 114.04 per cent. of 1,000 living in houses containing between 60 and 80 tenants. From this point it decreases with the adult death-rate.

27 These figures represent less than two hundred of the worst tenements below Houston Street.

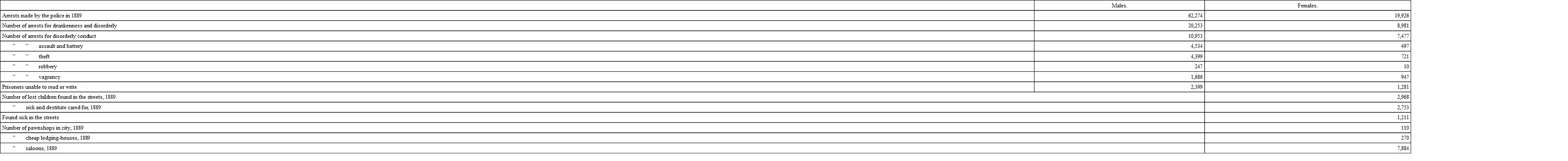

Police Statistics.

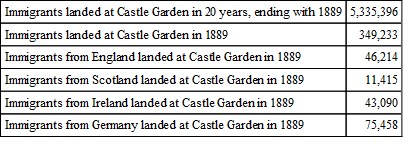

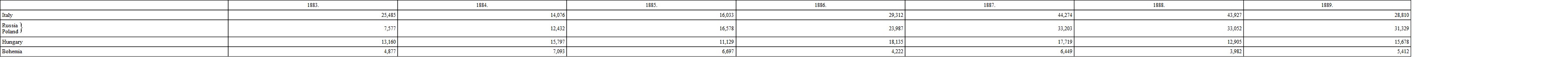

Immigration.

Tenements.

Corner tenements may cover all of the lot, except 4 feet at the rear. Tenements in the block may only cover seventy-eight per cent. of the lot. They must have a rear yard 10 feet wide, and air-shafts or open courts equal to twelve per cent. of the lot.

Tenements or apartment houses must not be built over 70 feet high in streets 60 feet wide.

Tenements or apartment houses must not be built over 80 feet high in streets wider than 60 feet.

1

Tweed was born and bred in a Fourth Ward tenement.

2

Forty per cent. was declared by witnesses before a Senate Committee to be a fair average interest on tenement property. Instances were given of its being one hundred per cent. and over.

3

It was not until the winter of 1867 that owners of swine were prohibited by ordinance from letting them run at large in the built-up portions of the city.

4

This “unventilated and fever-breeding structure” the year after it was built was picked out by the Council of Hygiene, then just organized, and presented to the Citizens’ Association of New York as a specimen “multiple domicile” in a desirable street, with the following comment: "Here are twelve living-rooms and twenty-one bedrooms, and only six of the latter have any provision or possibility for the admission of light and air, excepting through the family sitting- and living-room; being utterly dark, close, and unventilated. The living-rooms are but 10 Ã 12 feet; the bedrooms 6½ Ã 7 feet.“

5

“A lot 50 Ã 60, contained twenty stables, rented for dwellings at $15 a year each; cost of the whole $600.”

6

The Sheriff Street Colony of rag-pickers, long since gone, is an instance in point. The thrifty Germans saved up money during years of hard work in squalor and apparently wretched poverty to buy a township in a Western State, and the whole colony moved out there in a body. There need be no doubt about their thriving there.

7

The process can be observed in the Italian tenements in Harlem (Little Italy), which, since their occupation by these people, have been gradually sinking to the slum level.

8

The term child means in the mortality tables a person under five years of age. Children five years old and over figure in the tables as adults.

9

See City Mission Report, February, 1890, page 77.

10

Inspector Byrnes on Lodging-houses, in the North American Review, September, 1889.

11

Deduct 69,111 women lodgers in the police stations.

12

Report of Eastern Dispensary for 1889.

13

I refer to the Tenth Ward always as typical. The district embraced in the discussion really includes the Thirteenth Ward, and in a growing sense large portions of the Seventh and contiguous wards as well.

14

An invention that cuts many garments at once, where the scissors could cut only a few.

15

I was always accompanied on these tours of inquiry by one of their own people who knew of and sympathized with my mission. Without that precaution my errand would have been fruitless; even with him it was often nearly so.

16

The strike of the cloakmakers last summer, that ended in victory, raised their wages considerably, at least for the time being.

17

Suspicions of murder, in the case of a woman who was found dead, covered with bruises, after a day’s running fight with her husband, in which the beer jug had been the bone of contention, brought me to this house, a ramshackle tenement on the tail-end of a lot over near the North River docks. The family in the picture lived above the rooms where the dead woman lay on a bed of straw, overrun by rats, and had been uninterested witnesses of the affray that was an everyday occurrence in the house. A patched and shaky stairway led up to their one bare and miserable room, in comparison with which a white-washed prison-cell seemed a real palace. A heap of old rags, in which the baby slept serenely, served as the common sleeping-bunk of father, mother, and children—two bright and pretty girls, singularly out of keeping in their clean, if coarse, dresses, with their surroundings. The father, a slow-going, honest English coal-heaver, earned on the average five dollars a week, “when work was fairly brisk,” at the docks. But there were long seasons when it was very “slack,” he said, doubtfully. Yet the prospect did not seem to discourage them. The mother, a pleasant-faced woman, was cheerful, even light-hearted. Her smile seemed the most sadly hopeless of all in the utter wretchedness of the place, cheery though it was meant to be and really was. It seemed doomed to certain disappointment—the one thing there that was yet to know a greater depth of misery.

18

Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, Case 42,028, May 16, 1889.

19

Colonel Auchmuty’s own statement.

20

This very mother will implore the court with tears, the next morning, to let her renegade son off. A poor woman, who claimed to be the widow of a soldier, applied to the Tenement-house Relief Committee of the King’s Daughters last summer, to be sent to some home, as she had neither kith nor kin to care for her. Upon investigation it was found that she had four big sons, all toughs, who beat her regularly and took from her all the money she could earn or beg; she was “a respectable woman, of good habits,” the inquiry developed, and lied only to shield her rascally sons.

21

“The percentage of foreign-born prisoners in 1850, as compared with that of natives, was more than five times that of native prisoners, now (1880) it is less than double.”—American Prisons in the Tenth Census.

22

In printing-offices the broken, worn-out, and useless type is thrown into the “hell-box,” to be recast at the foundry.

23

Dr. Louis L. Seaman, late chief of staff of the Blackwell’s Island hospitals: “Social Waste of a Great City,” read before the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1886.

24

Forty-fourth Annual Report of the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor. 1887.