полная версия

полная версияPorcelain

We see, therefore, that before the year 1770, when Cookworthy removed to Bristol, true porcelain had been made in more than one place in England, but not with enough success to allow the new ware to compete with the soft pastes of Worcester and elsewhere. So in France, although the new paste was introduced at Sèvres in 1769, it was only in 1774, so Brongniart tells us, that the manufacture of hard porcelain was firmly established.

Champion seems to have been on friendly terms with Cookworthy, and in 1773 he bought from the latter the entire patent rights. In the two previous years much of the new porcelain had been made. It is claimed for it in advertisements that, unlike the English china generally, it will wear as well as the East Indian, and that the enamelled porcelain, though nearly as cheap as the English blue and white, ‘comes very near, and in some pieces equals, the Dresden, which this work more particularly imitates.’ This is from a local journal of November 1772, and we may add that not only the ware was imitated, but also the well-known marks of Dresden.250

Now, if we turn from these general considerations to examine the nature of the West of England ware, we find some difficulty in drawing a line between the early, partly experimental, porcelain made at Plymouth and the later, more successful, products of the Bristol kilns. Nor will the mark, the alchemist’s sign for Jupiter251 (Pl. e. 83), first used on the Plymouth porcelain, help us much, for the same mark was certainly used to some extent after Cookworthy’s migration to Bristol.

To Plymouth we must attribute the plain white ware with a glaze of dull hue, disfigured by dark lines where the glaze lies thick in the interstices. Cookworthy, we know, attempted to make his glaze from the Cornish stone without the addition of any other substances.252 In other cases he followed the recipe given by the Père D’Entrecolles, and gave greater fusibility to the growan-stone by adding a small quantity of a frit made from a mixture of lime and fern ashes. Cookworthy even ventured to follow the Chinese plan, and applied the glaze to the raw or very slightly baked paste. The blue and white made by him, if we may judge from the little mug in the British Museum, with the arms of Plymouth and the date, March 14, 1768, was of very poor quality. The Oriental designs on his enamelled porcelain seem to have come to him by way of Chantilly. More successful was the plain white ware modelled in relief, in a way that often calls to mind the early work of Bow. A good example is the ‘Tridacna’ salt-cellar in the former Jermyn Street collection.

PLATE XLVIII. 1—BRISTOL, WHITE BISCUIT

2—BRISTOL, COLOURED ENAMELS

At least one French modeller and enameller was employed at Plymouth, and after the removal to Bristol we find the name of a German also. Henry Bone, a Truro man, who afterwards became famous as a miniature-painter in enamels, entered the works at Bristol as a lad, and passed there the six years of his apprenticeship. Bone, who later on wrote R.A. after his name, was the principal representative in England of the school of painters in enamel upon slabs of porcelain, that played so important a part at Sèvres at the beginning of the last century. At one time a modeller of some skill must have been employed. Perhaps this was the mysterious Soqui or Le Quoi.253 Some little statuettes in the Schreiber collection at South Kensington, ‘the Seasons,’ as represented by boys and girls, are charmingly modelled. But we must not look for any brilliancy of colour in the enamels. The highly infusible nature of the paste, and what is even more important, of the glaze, added immensely to the difficulty of obtaining anything of the kind. If we compare the enamels on these statuettes with those on the Chelsea and Derby figures in the same collection, the difference is at once apparent. The two most important colours in the latter wares, the rose-pink and the turquoise, it was impossible to develop at the high temperature required to soften the refractory glaze of the hard porcelain. The greens, however, and the coral reds of the Bristol figures are more successful. In the specifications of 1775 there is mention of a glaze containing much kaolin mixed with some arsenic and tin oxide.254 Such a glaze might allow of more brilliancy in the enamels, and it is to be noticed in this connection that some statuettes long classed as Chelsea have only comparatively lately been recognised as consisting of the Bristol paste.

Perhaps what we may regard as the most remarkable, certainly the most original, work produced by Champion are the little circular or oval plaques of white biscuit. These medallions vary from four to nine inches in diameter. The central field contains a coat-of-arms modelled in low relief, or more rarely a portrait bust, and among these last we find heads of Benjamin Franklin and of George Washington, pointing to the political sympathies of Champion. A wreath of flowers in full relief surrounds the field—the sharpness and the finish in the modelling of these minute leaves and blossoms has never been approached in this or other material. In the manner of treatment, these wreaths are thoroughly English, and we are reminded of the flowers carved in wood by Grinling Gibbons (Pl. xlix.).

Champion made also a commoner ware, which he called ‘cottage china.’ This was summarily decorated in colours without any gilding. The glaze on this ware was applied over the raw paste, on the Chinese plan that had already been tried by Cookworthy.

Champion was an active politician and a vehement supporter of the American colonists in their dispute with the mother country. The visit of Edmund Burke to Bristol in 1774, and his election as member for the city, may be regarded as the climax of his career. Then it was that the famous tea-set was presented by Champion and his wife to Mrs. Burke, as a pignus amicitiæ. Still more elaborately decorated was the other service that Burke gave to Mrs. Smith, the wife of the friend of Champion, at whose house he stayed on this occasion. The shapes and the decoration of this service were founded on Dresden models, and the wreaths of laurels that formed an essential part of the design afforded a good field for the display of the green colour in which Champion excelled.

PLATE XLIX. 1—BRISTOL, WHITE BISCUIT

2—BRISTOL, WHITE GLAZED WARE

But Champion’s troubles were now to begin. In 1775 his petition to Parliament for a renewal of his patent was vigorously opposed by Wedgwood. Champion must have been put to great expense—he exhibited before a committee of the House some selected specimens of his porcelain. He, however, won his case, though the monopoly in the employment of the Cornish clays was restricted to their use as a material for transparent wares, a point of some importance to the Staffordshire potter. But meantime the American War was ruining his business—for Champion was in the first place a merchant trading with the West Indies and America—and it is probable that little porcelain was made by him after 1777. The next year Wedgwood, his inveterate opponent, in a letter to Bentley, says of him, ‘Poor Champion, you may have heard, is quite demolished.... I suppose we might buy some Growan-stone and Growan-clay now upon easy terms.’ In 1781, after a long negotiation, he disposed of his patent to some Staffordshire potters, and shortly after this he emigrated to America. Champion was only forty-eight years old when, in 1791, he died at his new home in South Carolina.

As Professor Church has pointed out, the paste of the Bristol porcelain is of exceptional hardness. It is, in fact, in some specimens as hard as quartz, that is, say, the hardness is equal to 7 in the scale of the mineralogist: the hardness of Oriental porcelain, it will be remembered, varies between 6 and 6·5; the glaze on the Bristol china is about 6 on the same scale. The fractured surface may be described as subconchoidal and somewhat flaky, with a greasy to vitreous lustre. On the Plymouth and Bristol wares, especially on the larger vases, may often be seen, when viewed in a favourable light, certain spiral ridges, the result of the unequal pressure of the ‘thrower’s’ hand. Similar ridges may indeed be observed at times on other hard paste wares, both Chinese and European, and this ‘wreathing’ or vissage, as Brongniart long ago pointed out, is the result of the too great plasticity of the clay,—a clay may, in fact, be too ‘fat’ to work well on the wheel. This plasticity, however, would be of advantage to the modeller, especially when working on a very small scale; indeed the delicate floral reliefs in biscuit, on the plaques we have already spoken of, could only have been made from a fine and unctuous clay. How refractory to heat this same paste is, was well proved by the fire at the Alexandra Palace in 1873, when so many fine specimens of English porcelain were destroyed. A biscuit plaque or medallion of Bristol porcelain passed uninjured (by heat at least) through this fire, while the soft porcelain alongside of it was completely melted.

The paste, then, of this Bristol ware is remarkable both for its resistance to heat and for its great plasticity. These are both qualities that point to an excess of kaolin in its composition, and this excess is confirmed by analysis. Professor Church found in a specimen of Bristol china 63 per cent. of silica, 33 per cent. of alumina, and only 4 per cent. of lime and alkalis. The percentage of alumina is about the same as that in the hard pastes of Meissen and of Sèvres, but the small amount of the other bases is quite exceptional. A paste of this composition would contain about 65 per cent. of kaolin.

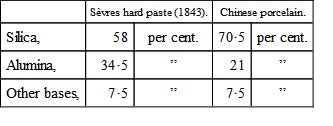

And here, before ending, we may for a moment return to what is, perhaps, the crucial point of all in the composition of true porcelain—for it is one that has a radical influence both on the technical and on the artistic side. The first question we must ask when inquiring into the composition of any specimen of porcelain is this—What proportion of kaolin enters into its composition? Or if it is a matter of the primary constituents of the paste—What is the percentage of alumina that it contains? Now we may consider the composition of kaolin, after removing the water, to be silica 54 per cent. and alumina 46 per cent., and the nearer the composition of our porcelain approaches to these figures, the greater will be its hardness, its resistance to fire, and the greater also the plasticity of the paste—the greater in fact will be what we have called the ‘severity’ of the type.255

Now for the other component of porcelain, the petuntse or china-stone. The composition of this material differs widely, but let us take the mean of some analyses of Cornish stone. On this basis we may take silica 72 per cent., alumina 18 per cent., other bases 10 per cent., as our type. The result of adding such a material to our kaolin will be to increase the percentage of silica and of the ‘other bases,’ and to diminish the percentage of alumina in the resultant mixture. Our paste now becomes less plastic and the resultant porcelain more readily softened by heat, but at the same time less hard.

So far every one would be agreed. But the question now arises, are we to attribute this increased fusibility to the higher percentage of the other bases (these are, in the case of European porcelain, practically lime and potash), or in a measure at least to the increased amount of silica in the paste? We have here three variants, the silica, the alumina, and the ‘other bases,’ and the case is therefore somewhat complicated. I think, however, that the careful examination of any table giving the composition of various types of porcelain would show that up to a certain point an increase in the amount of silica promotes a lower softening-point in the paste, and this in cases where there is no important change in the proportion of the ‘other bases.’ I will illustrate this by comparing the composition of the severe hard paste of Sèvres on the one hand with an analysis of a mild type of Chinese porcelain on the other:—

No doubt, if the percentage of silica is further increased, say beyond 78 or 80 per cent., we get again a practically infusible body. But with a paste of this composition the resultant ware is no longer translucent—we pass from the region of porcelain to a true stoneware.

Thus we see that in composition a mild porcelain forms a middle term between stoneware on the one hand, and a severe porcelain on the other. In other words, stoneware cannot be regarded as an extreme type of a refractory porcelain.

CHAPTER XXIII

CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN PORCELAIN

WE have seen that in England the new aims and the new schemes of decoration that have so profoundly affected most of our industrial arts have so far had little influence upon the porcelain manufactured by the large Staffordshire firms. Here and there, as by Mr. Bernard Moore of Longton, an attempt has been made to take up the problem of the flambé glazes, which has so fascinated the French potters. Mr. Moore has succeeded in making some sang de bœuf vases which in outline and colour closely follow the Chinese models. Otherwise the many skilful artists—more than one of them, I think, are Frenchmen—employed by our porcelain manufacturers have been content to follow in the main the old traditions, nor has any occasional attempt that has been made to imitate, not the latest but rather the work of the last generation at Sèvres, produced any very satisfactory results. It cannot be denied that both in the design and in the decoration our English porcelain has, for some time, remained outside the art movement of the day.

Indeed at the present time, and for the last twenty years, whatever of interest we can find in the contemporary production of porcelain, centres in two factories—Sèvres and Copenhagen. To the latter works we must now return for a moment.

The royal factory, of which we have already spoken, was closed after the disastrous war of 1864. But during the eighties a number of able men, both artists and men of science, occupied themselves with the new porcelain problems, and in 1888 a fresh company was formed, the ‘Alumina.’ These men—I will only mention Philip Schou—were much impressed by the technical and artistic merits of the porcelain lately sent from Japan, highly finished ware decorated under the glaze with great delicacy and generally in subdued colours. They were influenced above all by the work of the Japanese potter Miyagawa Kozan, called Makudzo. The Danish porcelain produced during the nineties is distinguished as a whole by its cool, subdued colours, with a prevalence of various pearly tints approaching more or less to celadon. In the carefully executed but boldly designed decoration, we see the influence both of the Japanese naturalists and of the impressionist painters of the day. The snow scenes, the rocks, the dancing waves and the sea birds have been suggested by the stormy coasts of the Baltic and the North Sea. It is from the primitive rocks of this coast that the pure felspar, which plays so large a part both in the paste and in the glaze, has been obtained.

It was at Copenhagen probably that the crystalline glazes, derived from salts of bismuth, were first made—this was by Engelhart, about 1884.

At a rival Danish factory—that of Bing and Gröndhal—many clever artists, some of them ladies, have modelled in porcelain figures of animals either in the round or in relief on the sides of vases: we find dogs, cats, and even seals (but not the human figure). Indeed in this kind of work something in the nature of a school has grown up.

Fresh life has lately been given to the old works at Rörstrand, near Stockholm. Here in the underglaze decoration the same cool, pearly colours that we find in favour at Copenhagen are predominant. Great care has lately been devoted to the modelling of flowers.

At the Rozenburg works, near the Hague, a new paste has been invented by Juriann Kok. The extraordinary tenacity and plasticity of this material allows of its being worked into the strangest forms—some of the vases, with long, thin, angular handles, suggest work in hammered metal. By means of a fantastic decoration—quaint, elongated figures, and forms of marine life, such as the long-clawed Japanese lobster—a certain original cachet has been given to this ware.

The Charlottenburg works, near Berlin, have lately felt the influence both of Copenhagen and of the new school of Sèvres. Everything has been lately tried—sculpturesque developments in various directions, and again the decoration of large wall surfaces with porcelain plaques enamelled so as to resemble oil pictures; but as in former days, so now, the technical and scientific side of this industry tends to prevail over the artistic.

M. Édouard Garnier, the late director of the Museum at Sèvres, in a report upon the porcelain exhibited at Paris in 1900, has ably summed up his impressions of the wares now being manufactured in various parts of Europe, and I cannot do better than follow so excellent an authority in his ‘appreciations’ of this modern porcelain.

M. Garnier dates the latest renaissance of European porcelain from the new ground struck out in the seventies, not only at Sèvres, by Deck and others, but also in many private kilns, as by Bracquemont in Paris and by Haviland in the Limoges district. What specially distinguishes the latest work is the advantage taken of the new colours that can now be employed with the grand feu so as to participate in the brilliancy and purity of the glaze. A delicacy of tone, a transparency and a harmony are now obtainable which contrasts favourably with the dry and dull colours of the old methods of painting. On the other hand, says M. Garnier, the progress in chemical knowledge has been so rapid that the new processes and colours have tended to become the masters of the artists who employ them, instead of remaining subtle tools in their hands.

This tendency is especially noticeable at Copenhagen, and the crystalline glazes, derived from bismuth, that have spread thence all over Europe, are a case in point. So again, starting from the flambé glaze of the Chinese, the modern potter is inclined to run riot with the numerous new materials at his command.

At Sèvres—I follow M. Garnier’s report—advantage has been taken of the new porcelain paste (that of the ‘milder’ Chinese type) to revive in the biscuit ware the reproductions of works of sculpture for which the factory was so renowned in the days of the pâte tendre. The pureness and softness of the material and the skill of the manipulation are noteworthy apart from the artistic merit of the work. (Let me here call attention to the fifteen figures by Léonard, ‘Le Jeu de l’Écharpe,’ in the new biscuit ware.) This revolution in the style of decoration has now spread to other parts of France, and has affected the great commercial factories of the south-west, especially the ware made by the firm of Haviland.

English porcelain was but poorly represented at Paris in 1900; besides, as we have said, it is in other branches of the potter’s art that we have to look for a reflection of our new native school of decoration. It is indeed a curious fact that many of the designs that we associate with Morris and his followers may be found rather upon the wares of Copenhagen and Sèvres than on our English porcelain. I cannot, however, pass over some criticisms of M. Garnier, in which he falls foul of certain tendencies in the fashioning and decoration of the wares turned out by our big Staffordshire firms. As to how far these criticisms are merited, any one may form an opinion for himself by a glance at the shop-windows of London. ‘The English paste,’ says M. Garnier, ‘is of a special nature which lends itself admirably both to the shaping and to the decoration; the execution is hors ligne, but this is accompanied by an overloading of detail, a heaviness in the decoration, and a want of harmony and proportion between the different parts of the piece that cause one to regret that so much talent and care have been employed only to arrive at so very unsatisfactory a result. Besides this, we notice in the English céramiste a want of sincerity, with the result that at first sight you cannot tell what manner of substance you are looking at, whether it is porcelain or dirty ivory, or again a gilt ceramic ware rather than a bronze with a poor patina.’ A curious point in connection with this criticism is that, if I am not mistaken, a good deal of the work thus severely dealt with has been designed, if not executed, by French artists. It is made, however, to satisfy the demand of our great unleavened middle-class.

Turning to the porcelain from the royal works at Charlottenburg, M. Garnier finds fault with the exuberance and overloading of the sculptures and reliefs. But certain large architectural pieces and some frames in rococo style, in pure white ware, excite his admiration, for the beauty of the paste, the purity and the limpidity of the glaze, and the marvellous way in which the technical difficulties of the execution have been surmounted; so, too, for the brilliancy of the colouring and the way in which the enamel colours combine with and form one material with the glaze, as if one were looking at a soft-paste ware. Above all, in some pieces of the ‘new porcelain’—for the milder paste is now in use at Berlin to some extent—the colours of the grand feu and the purity of the enamel are remarkable.

At Meissen, says M. Garnier, they are still working on the old lines: reproductions of the models made a century and a half ago by Kändler are as much as ever in demand. Certain ambitious attempts in a newer style have resulted in errors that will add nothing to the fame of the works. (Dr. Heintze, the present director, has especially devoted himself to the development of the new colours under the glaze. But the porcelain now produced, apart from the copies of the old wares, follows in the lines either of the Copenhagen porcelain, or again, at times, of the coloured pastes of Sèvres.)

Certain districts of Northern Bohemia have become of late centres of ceramic industry. The predominant bad taste and over-decoration of the porcelain made there (I still follow M. Garnier) is above all exemplified in certain coloured statuettes, ‘articles de bazar which corrupt the taste of the public and whose sale ought to be prohibited.’ An exception must be made for the produce of the Pirkenhausen works, near Carlsbad. The marvellous plasticity of the paste, made from the rich deposits of kaolin near Zottlitz, has been taken full advantage of, not only on the wheel and in the mould; it has allowed also of the free modelling of the superadded reliefs by the artist’s hand.

The factory at Herend, in Hungary, founded in 1839, no longer turns out the ware of Oriental style, so much admired by Brongniart, by Humboldt, and by Thiers. Herr Fischer, the director and principal artist, has lately made good imitations of the coloured pastes of Sèvres, with leaves and branches in relief.

At St. Petersburg the imitation of the over-decorated hard paste of Sèvres has been abandoned in favour of the soft and harmonious colours and the pure and limpid glazes of Copenhagen. The vases with designs of white paste, in relief upon coloured grounds, in a manner now little in favour at Sèvres, are less happy. At the Kousnetzoff factory, at Moscow, a polychrome decoration, in imitation of Byzantine embroideries and enamels, has been applied to tea-services of somewhat geometrical forms, while the French porcelain of the time of Louis Philippe continues to be imitated.

At Copenhagen, says M. Garnier, the new porcelain, which since its introduction in 1889 has been praised and exalted in all the art journals of Europe, is still produced on the same lines. Not to speak of the new and strange results already obtained from coloured and enamelled glazes, greater experience in the use of the extended palette at the command of the decorator has produced results in which we find an admirable delicacy and restraint. It was, however, from Sèvres that the impulse first came. We can trace it in the work turned out of late years by Messrs. Bing and Gröndhal. But in place of the amiable and gracious art of France we find here a severe, sometimes we might almost say a rude, style, but one not without character and elevation.