полная версия

полная версияPorcelain

Smaller West of England Soft-Paste Factories.

This will be the most convenient place to say something of a small group of factories where china was made towards the end of the eighteenth century. It is a distinctly West of England family, owing its origin in a measure to Worcester, but also forming a link between that factory and the Staffordshire works. We include in it the Shropshire porcelains of Caughley and Coalbrookdale, together with Swansea and Nantgarw.

Caughley.—The ‘Salopian Porcelain Works’ were started in 1772 at Caughley, near Broseley, in Shropshire, a neighbourhood long famous for its earthenware. It was here that Thomas Turner, a man of some social standing who came from Worcester, devoted himself more especially to printing in blue under the glaze. It was at Caughley, it would seem, about 1780, that the famous ‘willow pattern’ was first used. There is in the British Museum a curious little oblong dish that shows this design in an undeveloped form. Turner, it is said, first printed complete dinner-services, in dark blue, with this pattern. Not long after this he went to France, and brought back a batch of French painters, whose influence may perhaps be seen in the ware made at a later time at Coalport. Some of the printed work is delicately executed, and when the decoration is judiciously heightened with a little gilding, the effect is not unpleasing. We hear also of dinner-services painted with ‘Chantille sprigs,’ and Turner also supplied Chamberlain with plain white ware to be subsequently decorated at Worcester. At a later time much gilding was applied to a richly decorated porcelain. Some of this ware is stamped with the word ‘Salopian,’ other pieces have the letters S or C printed or painted under the glaze; but both Dresden and even Worcester marks were also used. Two men, at a later time representatives of the industrial phase of porcelain, John Rose and Thomas Minton, were trained in these short-lived works.

Coalport or Coalbrookdale.—Here, on the left bank of the Severn, nearly opposite the last-named factory, John Rose began making porcelain soon after 1780. In 1799 he purchased from Turner (whose apprentice he had been) the Caughley works, and in 1814 he removed the whole plant to Coalbrookdale. Here, too, came Billingsley after the closing of the Nantgarw works, and here he worked till his death in 1828. During the first half of the nineteenth century the firm of John Rose and Company was a successful rival to the Davenports, Mintons, and Copelands. Rose excelled in the production of gorgeous vases decorated with picture panels, and Billingsley kept up the supply of his English roses. The older wares of Sèvres and Chelsea were copied not unsuccessfully, and the appropriate mark was not omitted. The firm seems to have above all prided itself upon the beauty of its rose Pompadour grounds, and at a later time, after 1850, both this ground and the turquoise blue were largely applied to the pseudo-Sèvres porcelain that found its way to the London china-shops. In 1820 Rose was granted a medal by the Society of Arts for a leadless glaze, compounded of felspar and borax. The factory at Coalport continues to produce much china on the same lines.

Near at hand, at Madeley, some very close imitations of the old Sèvres were made by Randall between 1830 and 1840. For the origin of this English Sèvres we must go back to the year 1813, when we hear of the agents of London dealers buying up white and slightly decorated Sèvres soft paste. Any enamel colour on them was removed by hydrofluoric acid, and the surface was richly decorated in the Pompadour style. Randall soon after this time was engaged with similar work in London: his turquoise blues are especially praised.

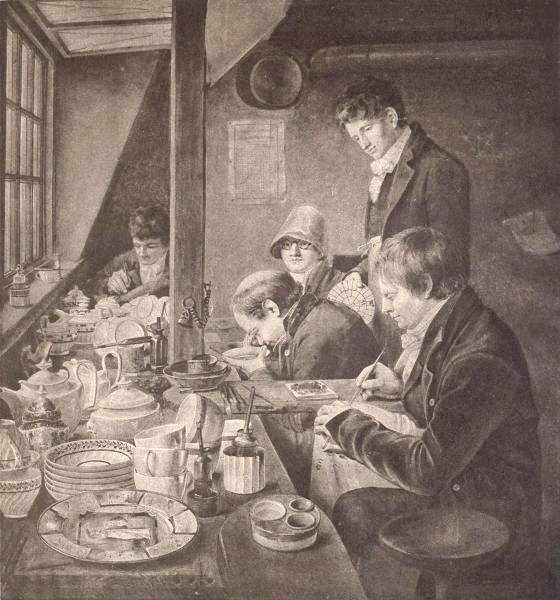

Plate XLVII

Water-colour Drawing. Enamel Painters at work.

Swansea and Nantgarw.—At the beginning of the nineteenth century some works at Swansea, where a so-called ‘opaque porcelain’ had been lately manufactured, were purchased by Mr. Lewis W. Dillwyn. Mr. Dillwyn was a keen naturalist: he induced Mr. Young, a draughtsman who had been employed by him in illustrating works on natural history, to learn the art of enamel-painting on porcelain. Young devoted himself to painting birds, shells, and above all butterflies. In spite of the aim at scientific accuracy, the artistic effect of these delicately painted butterflies, scattered here and there over the dead white paste, is not unpleasant. There were some good specimens of this form of decoration in the old Jermyn Street collection, but most of them, I think, are not painted on a true porcelain.

Meantime, at Nantgarw (Anglicè Nantgarrow), some ten miles north of Cardiff, a small porcelain factory had been established by one William Beely and his son-in-law, Samuel Walker.

Mr. Dillwyn, who visited the Nantgarw works in 1814, at the instigation of his friend Sir Joseph Banks, found these two men making an admirable soft-paste porcelain, remarkable for its translucency. ‘I agreed with them,’ so Mr. Dillwyn reported, ‘for a removal to the Cambrian pottery [i.e. to Swansea], where two new kilns were prepared under their direction. When endeavouring to improve and strengthen this beautiful body, I was surprised at receiving a notice from Messrs. Flight and Barr of Worcester, charging the parties calling themselves Walker and Beely with having clandestinely left an engagement at their works.’

Beely was in fact no other than Billingsley, the wandering artist and ‘arcanist’ who in 1774 was apprenticed to Duesbury at Derby, and had there learned the art of painting flowers on porcelain. We hear that in 1793 he was also landlord of the ‘Nottingham Arms,’ but in spite, or perhaps rather in consequence, of thus having two strings to his bow, he soon after left Derby, and for twenty years led a roving life. In 1796 he was at Pinxton, and it was here, says Mr. W. Turner (The Ceramics of Swansea and Nantgarw), whom I now follow, that he perfected his famous granulated frit body. Then follows an obscure period, during which we hear of Billingsley at Mansfield, and again as a china manufacturer at Torksey, in Lincolnshire. Finally, in 1808, he settled down to work at Worcester under the name of Beely. His later migrations to Nantgarw, to Swansea, and finally to Coalport, we have already referred to.

Three years after Billingsley’s removal to Swansea, the manufacture of porcelain was abandoned by Mr. Dillwyn: this was in 1817, barely six years from the time when Billingsley started the Nantgarw works.

It is not quite certain whether the marks that distinguish the two wares—‘Nantgarw’ above the letters ‘C. W.’ in one case, ‘Swansea’ sometimes with the addition of a trident (Pl. e. 80) in the other—can always be relied on to distinguish the two factories: the former mark may have continued in use after the removal to Swansea.

The paste of some of the ware made at Swansea was very different from that of Billingsley’s glassy porcelain. We know that both china-clay and steatite from the Lizard were employed here, producing a somewhat hard and opaque body.

Apart from their paste, renowned for its absolute whiteness and considerable translucency, Billingsley and his pupils, Pardoe and Walker, have acquired a certain fame by their enamel-painting on this Nantgarw porcelain. Life-size roses, auriculas, tulips, and lilies were their favourite flowers. This was the culmination, as it were, of the school that delighted above all in the double rose, a not very paintable flower, at least in a decorative point of view. We saw its beginnings at Derby more than thirty years before this time. But Baxter the younger, whom we have come across at his father’s workshop in Gough Square, painted figure-subjects on the Swansea porcelain, and some of the translucent ware of the Nantgarw type was sent up to London unenamelled, there to be converted into the old soft paste of Sèvres.

Before we return to the West of England to treat of the true hard porcelain of Plymouth and Bristol, there remain to be mentioned briefly a few unimportant factories of soft paste—unimportant, that is, from the point of view of art.

Lowestoft.—Taking advantage of some suitable clay found in the neighbourhood, and of the fine silvery sand of the shore, a manufactory of soft paste was established at Lowestoft about 1756. Later on we find some references to a ‘Lowestoft Porcelain Company.’ The ware produced was chiefly blue and white, with views of the neighbourhood, but other small pieces are found crudely painted in colour. The execution of much of this ware is very summary, and the glaze is often dull and spotted. A blue and white plate in the British Museum, with poudré ground and panels painted with views of Lowestoft and the neighbourhood, is an unusually favourable specimen. More commonly we find jugs and ink-pots with inscriptions—‘A Trifle from Lowestoft,’ etc.—and with dates in one or two cases ranging from 1762 to 1789. Whether any hard porcelain from other sources was ever painted at Lowestoft is very doubtful.242

The ‘Lowestoft porcelain’ of the dealers is now known to have been painted by Chinese artists at Canton. That this is so was conclusively proved many years ago by Sir A. W. Franks. The thrashing out of the question had the advantage of throwing much light on the origin of this curious pseudo-European decoration. The greater part of this porcelain painted at Canton is covered with elaborate armorial designs, and it was made not only for England but for other European countries that traded with the East. The history of this Sinico-European ware is well illustrated in a large collection brought together chiefly by the late Sir A. W. Franks and now in the British Museum.243

Liverpool.—Pottery had been an article of export from Liverpool from an early date, and much of the ware exported (it went above all to America) was made in the neighbourhood. During the sixties of the eighteenth century more than one of the local potters began to make a soft-paste porcelain. One of these men—Richard Chaffers—we find scouring the county of Cornwall in search of soap-stone and china-clay, as early probably as the year 1755. Professor Church gives the recipe for the ‘china body’ used in 1769 by another potter—Pennington. The materials are bone-ash, Lynn sand, flint, and clay,244 the latter probably from Cornwall.

There is a good deal of uncertainty as to the identification of the Liverpool china: some of it has perhaps been classed as Worcester or Salopian. Examples of the ware attributed to this town may be found at South Kensington; they are somewhat rudely printed in a heavy dark blue. But it is probable that very little true porcelain was made at Liverpool in the eighteenth century.

Early in the next century an important factory for pottery and porcelain was founded on the opposite side of the Mersey, and thither many workmen were brought from Staffordshire. Porcelain was made there until the year 1841. The ware was marked ‘Herculaneum,’ the name of the works. We find at times a bird holding a branch in its beak used as a mark. This is the ‘liver,’ the crest of the town of Liverpool. The liver, indeed, is occasionally found on ware of an earlier date.

Pinxton.—Our chief interest in the factory established in 1795 at Pinxton, on the borders of Derbyshire and Northampton, by John Coke, is derived from the temporary residence there of Billingsley. This was his first stopping-place after leaving the Derby works: here he remained until 1801, and it was here, probably, that he developed the ‘china body’ used by him afterwards at Nantgarw. There were some pleasing specimens of the Pinxton ware in the old Jermyn Street collection simply decorated with ‘French twigs’ in blue and green. The ice-pail at South Kensington, with canary ground and frieze of roses, illustrated in Professor Church’s little book, was probably painted by Billingsley.

At Church Gresley, in the extreme south of Derbyshire, an ambitious attempt to make a porcelain of high quality nearly ruined Sir Nigel Gresley, the representative of the old family long settled there. This was in 1795, and after three successive owners had sunk their fortunes in the factory, the works were finally closed in 1808. I can point to no example of porcelain that can with certainty be attributed to these kilns. Pottery and encaustic tiles are, however, still made in the district.

Rockingham Porcelain.—At Swinton, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, not far from Sheffield, pottery-works were established in the eighteenth century on the estates of the Wentworth family. These potteries were called after the Marquis of Rockingham, who was more than once at the head of the Government, and the name was carried over to the porcelain which was made there by Thomas Brameld in the next century. This factory was in existence from 1820 to 1842, and the ware turned out well represents the taste of the time. ‘Brameld,’ we are told, ‘spared no labour or cost in bringing his porcelain to perfection, and in the painting and gilding he employed the best artists.’ The ornate dinner-services made by him for William iv. and other royal personages probably surpassed in elaborate decoration and expense of production anything of the kind ever made in England. At South Kensington is a gigantic vase—it is more than three feet in height,—on the top is a gilt rhinoceros, an oak branch embraces the sides, the base is modelled in the form of three paws, and the whole body of the vase is covered with a series of highly finished pictures, chiefly flower pieces. This vase is a unique example of everything that should be avoided in the modelling and decoration of porcelain. On some of the Rockingham china we find a griffin as a mark, in honour of Lord Fitzwilliam, who had succeeded to the Wentworth estates on the death of his uncle, Lord Rockingham.

Already, at the commencement of the nineteenth century, the manufacture of porcelain in England was beginning to be concentrated in the hands of a few large firms in the pottery district of North Staffordshire, and here a definite type of ‘china body’ was established suitable for practical use. Bone-ash mixed with china-stone and china-clay from Cornwall were and still remain the essential constituents of this paste: to these materials ground flints are sometimes added.

Although it is apart from our purpose to trace the history of the great Staffordshire firms, we must say a word of one family—the Spodes of Stoke-upon-Trent. The firm founded by them was in a measure the common centre from which the later establishments had their origin. Josiah Spode the elder had been making pottery of various kinds at Stoke since the year 1749; he it was who introduced the blue willow pattern to the Staffordshire potteries. It was to his son, the second Josiah, that the credit of first using bone-ash as an ingredient of porcelain was so long ascribed. The statement thus put is of course absurd. His real merit lay in abandoning the use of a frit and adopting a china-body consisting simply of a mixture of china-stone and china-clay from Cornwall, with a large proportion of bone-ash, and thus settling once for all the composition of the industrial porcelain of England, a ware differing in many respects from the eighteenth century soft pastes, and one capable of being manufactured on a large scale without the risks that always attended the firing of the latter. His ‘felspar porcelain,’ often so marked, is of less consequence, but by using pure felspar instead of china-stone he forestalled the practice since adopted by many continental works, where felspar of Scandinavian origin is now largely used.

Later on, when William Copeland joined the firm, they became the most important makers of porcelain and earthenware in England, and the Continent was inundated with their wares. The founder of the rival firm of Minton was a Shropshire man: at the end of the eighteenth century he had been apprenticed to Turner at Caughley, and he, too, worked at one time in the Spode factory. At a later date both firms claimed the credit for the invention of an improved kind of biscuit, the Parian ware, of which much was heard about the middle of the last century.

There is at South Kensington a representative collection of the finer Spode wares, presented by a niece of the second Josiah. Great technical perfection was attained, and the enamel colours are remarkably brilliant and effective. I have already referred to a large tray, on which the brocade pattern of the old Imari is seen in the last stage of decay. The elements of the design have fallen to pieces, and lie helplessly scattered over the surface. Yet this is a carefully finished piece, and the enamels are of good quality. I take this tray as a typical example of a style of decoration with coloured enamels both on porcelain and earthenware which prevailed not many years ago on wares in domestic use. Along with the transfer-printed camaïeu mentioned on page 360, these wares found their way to most parts of Europe and America.

Belleek.—Probably the last attempt that has been made with us to establish a new factory of porcelain was at Belleek, near Lough Erne, in northern Ireland. Here, under the direction of Mr. Armstrong, a very fine and translucent paste was first made in 1857, and a peculiar nacreous lustre was given to the ware by the use of a glaze prepared with a salt of bismuth. The local felspar was employed together with china-clay brought from Cornwall. Some care was given to the modelling in imitation of shells and corals. Little of this ware, which may be classed as a hard-paste porcelain, has been made of recent years.

CHAPTER XXII

ENGLISH PORCELAIN—(continued)

THE HARD PASTE OF PLYMOUTH AND BRISTOLTHE manufacture of true porcelain had but a short life in England. The ware has no especial artistic merit, nor was it ever commercially of much importance. And yet in the history of this short-lived attempt to imitate the porcelain of China and Saxony, we find so many points (in the composition and technique of the ware above all) that illustrate and confirm what we have said in some early chapters, that we shall have to follow up this history somewhat closely.

Moreover, the two men, thanks to whose energy and scientific knowledge the difficulties attending the first manufacture of the new substance were overcome, interest us in more ways than one. There is, in the first place, Cookworthy the quaker, who, once he had solved the practical problem that had hitherto baffled all the potters and arcanists of England and France, was content to return to a quiet life among the little coterie of ‘friends’ at Plymouth. The other is Champion, the friend of Burke, who, after his business had been ruined by the American War, preferred to end his life as a farmer in the new country, with whose struggle for independence he had throughout sympathised.

The two letters of the Père D’Entrecolles on the manufacture of porcelain in China were known through their publication in Du Halde’s collection soon after the date (1722) at which the second one was written. The search for the essential constituents of a true porcelain at once began. One of the first results of this search was the appearance of the ‘Unaker, the produce of the Cherokee nation of America,’ which is mentioned in Frye’s patent of 1744. Shortly after the middle of the century, as we learn from Borlase’s History of Cornwall (published in 1758), the attention of more than one manufacturer of porcelain was directed to that county. But no one probably was so well equipped for the search as William Cookworthy, the druggist of Plymouth—he was already thoroughly acquainted with the geology of the county. Cookworthy, too, must have carefully studied the letters of the Jesuit missionary. In the memoir written by him at a later date (it is given in full in Owen’s Two Centuries of Ceramic Art at Bristol) he clearly distinguishes ‘the petunse, the Caulin, and the Wha-she,’ or soapy rock.245

In fact it is this that gives to Cookworthy so important a place in the history of porcelain. He was probably the first in Europe to attack practically, and finally to conquer, the problem of making a true porcelain strictly on the lines of the Chinese as interpreted by the Père D’Entrecolles. Böttger’s success, if one is to accept the official German account, was rather the result of some happy accident—an accident, it is true, of which only a man of genius knows how to avail himself.

Cookworthy had his attention directed to the subject by an American quaker, of whom he writes, in May 1745: ‘I had lately with me the person who hath discovered the China-earth. He had several examples of the China ware of their making with him, which were, I think, equal to the Asiatic; … having read Du Halde, he discovered both the China-stone and the Caulin.’246

Both the petuntse and the ‘Caulin’ were first identified by Cookworthy at Tregonnin Hill (between Marazion and Helston)—this was about 1750. The nature and mode of occurrence of both the growan or moor-stone and of the growan clay, to use the local names, are admirably described by him. Soon after this he found the two materials at St. Stephen’s, between Truro and St. Austell, in the centre of what is now the great china-clay district of Cornwall.

There must have been many experiments with the new materials, and many failures, before the year 1768, when Cookworthy took out his patent, and with the pecuniary assistance of Thomas Pitt of Boconnoc (later Lord Camelford) started his factory at Plymouth. It is doubtful whether this factory was in existence for more than two years. In any case there is evidence that already, by the year 1770, the ‘Plymouth New Invented Porcelain Manufactory’ was at work at Bristol.

We have proof, too, that before this time Richard Champion and others had been working in the latter town with the new Cornish materials. Champion had been asked by Lord Hyndford to make a report upon some kaolin sent to him from South Carolina. In his reply he says: ‘I had it tried at a manufactory set up some time ago on the principle of the Chinese porcelain, but not being successful, is given up.... The proprietors of the works in Bristol imagined they had discovered in Cornwall all the materials similar to the Chinese; but though they burnt the body part tolerably well, yet there were impurities in the glaze or stone which were insurmountable even in the greatest fire they could give it, and which was equal to the Glasshouse heat.... I have sent some [i.e. of the Carolina clay] to Worcester, but this and all the English porcelains being composed of frits, there is no probability of success.’ This is written in February 1766, before the date of Cookworthy’s patent.247

Meantime, in France, two men of some scientific pretensions, both of them members of the Académie des Sciences, Lauraguais248 and D’Arcet, had discovered the kaolin deposits near Alençon. Lauraguais had soon after 1760 succeeded in making some kind of porcelain with the materials he had found. He was, however, forestalled by Guettard, a rival chemist in the service of the Duke of Orleans, who in November 1765 read a paper before the Académie on the kaolin and petuntse of Alençon. Lauraguais, in disgust, after a violent rejoinder, came over to England.

In a curious letter dated April 1766, Dr. Darwin, writing to Wedgwood, says: ‘Count Laragaut has been at Birmingham & offer’d ye Secret of making ye finest old China as cheap as your Pots. He says ye materials are in England. That ye secret has cost £16,000—ytHe will sell it for £2000—He is a Man of Science, dislikes his own Country, was six months in ye Bastile for speaking against ye Government—loves every thing English’; but, adds Darwin, ‘I suspect his Scientific Passion is stronger than perfect Sanity’ (Miss Meteyard, Life of Wedgwood, vol. i. p. 436). Lauraguais, in 1766, proposed to take out a patent for making not only the coarser species of china, but ‘the more beautiful ware of the Indies and the finest of Japan.’ The specification was never enrolled, and nothing came of it. There exist, however, a few specimens of china marked with the letters B. L. (Brancas Lauraguais) in a flowing hand, which are attributed to the Count.249 The paste, says Professor Church, is fine, hard, and of good colour. An analysis gives 58 per cent. of silica, 36 per cent. of alumina, and 6 per cent. of other bases. It will be observed that the percentage of alumina in this porcelain is exceptionally high.