полная версия

полная версияPorcelain

The introduction, however, of the hard-paste porcelain at Sèvres dates from the discovery, in 1768, at Saint-Yrieix, near Limoges, of those famous deposits of kaolin which have ever since that time been the main resource of the French porcelain industry.194 Before the end of the year 1769 Macquer was able to show to the king the first samples of this new ware. The hard paste made for some years after this date was not of the ‘severe’ type adopted later on. Not only did it contain as much as 9 per cent. of lime, but, the kaolin employed being less pure, contained probably a good deal of mica—in fact, this first type of French hard paste approached in composition that of the Chinese. It is even more important to note that the glaze used at the same time was of an entirely different nature from the pure felspathic covering afterwards adopted. It was composed of Fontainebleau sand 40 per cent., potsherds of hard porcelain 48 per cent., and chalk 12 per cent. As a result, it was possible to decorate the surface with brilliant translucent enamels of some thickness.

It was the introduction of the felspathic glaze in 1780 that gave the final blow to the effective decoration of Sèvres porcelain. This glaze is made by simply fusing a natural rock (pegmatite) consisting of a mixture of potash felspar with a small quantity of quartz. The ease with which this glaze can be prepared, its hardness and uniformity of surface, led to its universal adoption not only at Sèvres but in the porcelain works of the Limoges district that have for the last hundred years supplied France with ordinary domestic wares—for such use its hardness renders it eminently suitable. But, as we have said, this combination of refractory paste and hard glaze is incompatible with any brilliancy of decorative effect, the enamel colours are quite unable to incorporate themselves with subjacent glaze, they lie dull and dead on the surface, and the faults of the German porcelain are exaggerated.

So with the paste, a much harder and more refractory type was introduced at the beginning of the next century, and (apart from the recent partial introduction of a milder type for special purposes) this type has remained in use to the present day. The lime in Brongniart’s new paste was reduced to 5 per cent., while the amount of kaolin (65 per cent.) is probably greater than in any other porcelain. There has been a reaction lately at Sèvres against this refractory ware, but the old formulas are still employed for the porcelain made for practical domestic use. When, however, brilliancy of effect and artistic decoration are aimed at, a completely new type both of paste and glaze has been in use since the year 1880, and concomitantly with the imitation of the Chinese monochrome wares, an attempt has been made to follow as closely as possible the pastes and glazes of the Chinese. M. Vogt, the present technical director at Sèvres, who has had so much to do with these changes, gives the following formula for the composition of the new porcelain: kaolin 38 per cent., felspar 38 per cent., quartz 24 per cent. The lime, it will be seen, has been completely eliminated from the paste; on the other hand, the glaze contains as much as 33 per cent. of the Craie de Bougival.

It would be a dreary task to enter with any detail into the history of the Sèvres works during the hundred years following the first introduction of the hard paste. This period is associated in most minds with the colossal vases that are to be found in so many of the palaces and museums of Europe. To judge from these examples, it would seem that the chief object both of the design and the decoration was to conceal as far as possible the nature of the material used in their composition. You have first to persuade yourself that you are looking at something made of porcelain: once convinced of this, you marvel at the technical difficulties that have been overcome in its manufacture, but what it never even occurs to one to look for in these monstrous vases, is any trace of that beauty of surface and brilliancy of decoration that we are accustomed to associate with the substance of which they are composed.

The ‘Medici Vase’ now in the Louvre is probably the earliest of this long series. This vase dates from the year 1783, and it is nearly seven feet in height. But it was in the pseudo-classical style of the empire, when encouraged by Napoleon’s love of the gigantic, and by his desire ‘à faire parler la porcelaine,’195 that this new application of porcelain found its full expression. It is then that we find vases, candelabra, surtouts de table and clocks, in styles distinguished as Egyptian, Etruscan, Imperial, and Olympian. After this we can follow the decline of taste in the succeeding régimes till, with the total extinction of all feeling for harmony of colour and unity of composition, we are landed—in the reign of the ‘bourgeois king’—in the style or absence of style which is the French equivalent of our ‘Early Victorian.’

There is one name above all others that is associated, at Sèvres, with this long period, that of Alexandre Brongniart, who was director of the works from the year 1804 until his death in 1847. The son of a well-known architect, and himself a fellow-worker with Cuvier, he attained some distinction both as a geologist and as a chemist. It was indeed from the point of view of a man of science that he approached the subject of ceramics,—as a geologist to examine the position and stratigraphical relation of any material suitable for fictile purposes, as a chemist to analyse these materials and to discover fresh metallic combinations suitable for glazes and enamels.

It was at this time, and chiefly under the influence of Brongniart,196 that the palette of the enameller was enlarged by the introduction of so many new colours, the employment of which gives a new cachet to the decoration of the nineteenth century. Perhaps the most important advance was in the employment of oxide of zinc in the flux, by means of which the colours of many metallic oxides are developed and sometimes altered. The green derived from chromium is essentially a nineteenth century colour, and as it resists the highest temperature this green can be used, like the cobalt blue, as an under-glaze colour. From the chromate of lead an orange-red is obtained—the rouge cornalia, a crude and dangerous colour, and one that does not withstand high temperatures. An orange-yellow from uranium, and a deep and uniform black from iridium, were also introduced at this time or not long afterwards. The ‘English pink,’ the lilac tint so extensively used in the transfer-printing of earthenware, was successfully imitated by adding a small quantity of oxide of chromium to a flux containing oxides of tin, lime, and alumina. The celadon green of Sèvres is derived, not from the protoxide of iron, but from the sesqui-oxide of chromium, with the addition of a minute quantity of copper.

Brongniart’s great work, the Traité des Arts Céramiques, still remains our main authority on the technical and scientific side of the art of the potter, and it was he who, by establishing the museum and organising the laboratories at Sèvres, made that town a centre for all who are interested not only in the special branch of porcelain, but in the whole field of ceramic art. The position established by him has been well maintained by his successors, by Salvétat, by Ebelmen, by Deck, and at the present time by MM. Lauth and Vogt on the technical side—above all by Édouard Garnier, the present director of the Sèvres Museum.197 These men have succeeded, in spite of much opposition, in again bringing the national manufactory of porcelain at least on to a level with the artistic movement of the day.

In tracing the history of the Sèvres porcelain during the last hundred years and more we can find at least one interesting aspect—we can follow the steps by which the ware has responded to the social and political changes that have followed one another in France during that time. The affectation of simple and homely tastes, and the sentimental tone fashionable in society during the years preceding the Revolution, are reflected in both the forms and the painting of the ware then made. The classical spirit that already in the time of Louis xvi. had found a place alongside of these idyllic aspirations somewhat later, under the lead of David, ruled every form of art. The various phases of the Revolution are reflected in the decoration of the porcelain, which even became a means of political propaganda. At the Hôtel Carnavalet, the museum at Paris consecrated to the history of the city, the political changes of this period may be traced in a series of plates and cups, some of them of Sèvres porcelain, decorated with emblems and allegorical figures relating first to the liberal monarchy of the early years of the Revolution, and then in the sterner days of the Convention (when indeed the existence of the works was only saved by the presence of mind of the minister Paré) to the patriotic efforts of the leaders, and to the successes of the republican armies. Portraits of the heroes of the national assemblies and of the clubs, surmounted by caps of liberty and framed in arrangements of pikes and drums, replaced the nymphs and flowers of an earlier period, and even the guillotine, it is said, has found a place in the decoration. A few years later the military element was even more predominant. Eagles and thunderbolts, surrounded by trophies of war, battle-scenes and the entry into Paris of the victorious legions, commemorate the conquests of Napoleon.

After the Restoration the decoration of the gigantic vases, each new one overtopping its predecessor, became more and more pictorial. To obtain a better field for this pictorial display the greatest pains were taken to produce large plaques of porcelain, some as much as four feet in length, on which a school of accomplished artists painted laborious reproductions of famous pictures, ancient and modern. Not a few of these enamel-painters, at this time, came from Geneva, and some of the ablest were ladies. Many remarkable specimens of this misdirected skill may be seen in the Sèvres Museum, and also in a room of the picture-gallery at Turin.

Under the republican régime that succeeded the revolution of 1848, it was again proposed for a moment to sever the connection with the State, but with the establishment of the second empire a fresh life was given to the manufactory, on the appointment of Dieterle, an artist of repute, to the directorship. Some new developments were now attempted, especially in the introduction of coloured pastes. It was only after many fruitless attempts that any results were obtained by this new system. It is indeed a process quite foreign to the nature of porcelain, and even when technically successful the result is far from satisfactory. At a later time, however, the experience gained by the experiments of Salvétat enabled a potter of great skill and some feeling for art to employ the coloured pastes with greater simplicity and better effect. M. Solon, since so well known in England, was the most successful worker in this material. The decoration in his hands took the form of a white slip, or barbotine, laid on a coloured ground. After firing, the light and shade of the design is brought out by the varying thickness of the now translucent coating, which allows more or less of the coloured ground to be seen through it. In spite of its delicacy and refinement the effect of this work is somewhat effete, both in style and colour. In inferior hands, working with poorer material, the result is deplorable.

At the present time, after experiments with many materials—the crystalline glazes made with bismuth were at one time in favour—it is to the production of artistic effects by means of single glazes that the greatest attention is given at Sèvres, following more or less in the lines of the flambé wares of China. Not long since, a proposal was again made in the Chamber of Deputies that the support of the Government should be withdrawn from the factory. It is said that a timely report in an English paper to the effect that, in such a case, the works would be run by an Anglo-American syndicate, had not a little to do with the defeat of this motion.

Lesser Parisian Factories of Hard Paste.—In spite of the numerous edicts and proclamations by which it was attempted to maintain the monopoly of the royal works at Sèvres, there were in Paris, in the time of Louis xvi., a number of private factories, some of them under the patronage of members of the royal family.

It was in Paris that Brancas Lauraguais, as early as 1758, made his experiments with kaolin, and here, in the Saint-Lazare district, one of the Hannong family (Pierre Antoine, of the third generation, the same who had lately failed at Vincennes) made porcelain after the German style, perhaps before 1770. These works were patronised at a later day by the king’s brother, the Comte d’Artois.

Again, in 1773, one Locré started in the Rue Fontaine au Roi the ‘manufacture de porcelaine Allemande de la Courtille.’ His marks of arrows (Pl. d. 59), torches, or later, ears of wheat, crossed in imitation of the Saxon swords, are found on ware of some artistic merit.

But perhaps the most remarkable of the Parisian factories was that started at Clignancourt, in 1775, by Pierre Deruelle, under the powerful protection of Monsieur (the king’s brother, afterwards Louis xviii.). The royal edicts (as indeed was often the case elsewhere) against the use of gold were ignored in this case, and the Sèvres ware—the simpler forms then in fashion—was cleverly imitated. The earlier mark, a windmill (Pl. d. 61), pointed to the famous moulin on the neighbouring Montmartre. At a later time the letter M, under a crown, referred to the royal patron.

The queen herself took under her patronage the factory started in 1778 by Lebœuf in the Rue Thiroux. This is the ‘Porcelaine de la Reine,’ marked with the letter A under a crown (Pl. d. 62), often decorated with leaves and little sprigs of the barbeau, the cornflower, then so much in fashion. These flowers, indeed, may be found on many other wares, English and French, about this time.

The Duc d’Angoulême was the patron of the works started in 1780, in the Rue de Bondy. It is noteworthy that this factory survived, still under the original founders, Guerhard and Dihl, to the days of Louis xviii. Dihl was, as it were, a forerunner of Brongniart, being the first potter in France to employ the newly discovered colours derived from rarer metallic bases. The Rue de Bondy factory had also the credit of producing elaborate copies of pictures on plaques of porcelain before such things were attempted at Sèvres.

The factory established in 1784 at the Pont aux Choux is chiefly remarkable for the patronage of the Duc d’Orléans, Philippe Égalité. Starting with the brother of Louis xiv., whose arms are found on gigantic vases of ‘old Japan,’ this was the fifth member of the Orleans family who had interested himself with porcelain, in one way or another.

I have only mentioned a few of the more important Parisian factories. Franks, in his Catalogue of Continental Porcelain, gives a list of seventeen works. Examples of most of these may be found either in the Franks collection or in that of Mr. Fitzhenry.

After the Restoration the work done in Paris became more and more confined to the decoration of porcelain made elsewhere. A special industry—for such it may well be called—was the imitation of older wares, both Oriental and European. For this somewhat ambiguous work the Samson family has acquired a European reputation.

At the present day many more or less amateur potter-artists are working in Paris. Specimens of their work may be studied in the yearly salons. It is no uncommon thing to see—in the neighbourhood of the Panthéon, for instance—a notice in a window pointing out to those interested, that a kiln for porcelain or fayence will be fired at such and such a date.

During the last hundred years Limoges has become more and more the centre of the porcelain industry of France. A very hard, refractory porcelain is here made from the excellent kaolin of Saint-Yrieix, and this ware not only occupies in France the position of our Staffordshire earthenware and semi-porcelain, but competes with these wares in the markets of the world. One of the largest works was started some years ago with American capital, and the United States, until lately, drew their principal supplies of porcelain from this district.198 It is to a chemist attached to one of these factories, to M. Dubreuil, that we are indebted for our best account of the technical and chemical processes employed at the present day in the manufacture and decoration of porcelain (see the work quoted on p. 15). At Limoges there is a ceramic museum, the most important in France after that at Sèvres, the contents of which have been described by M. E. Garnier in a catalogue which, as far as continental porcelain is concerned, has, so far, no rival.199

CHAPTER XIX

THE SOFT AND HYBRID PORCELAINS OF ITALY AND SPAIN

THE porcelain made in Italy in the eighteenth century is not of much importance either from a technical or an artistic point of view. With the exception of the Capo di Monte ware and its imitations, examples are rarely found in English collections. On the whole the decoration is poor in effect, and closely follows in the wake of the German wares. This is the case at least with most of the porcelain made in the north of Italy. Following, probably unconsciously, the example of the early Medici ware, the refractory element in the eighteenth-century porcelain of Italy has generally been found in a natural kaolinic clay which here replaces the quartz-sand and the lime of the French soft paste, and it is this peculiarity in their composition which led Brongniart to form a special class for what he called the hybrid pastes of Italy.

Venice.—There is, as we have seen, strong evidence that porcelain was made in Venice in the sixteenth century, but such evidence is, unfortunately, only documentary. We are in almost as bad a position when we come to the ware manufactured in the city, perhaps as early as 1720, by the Vezzi, a family of lately ennobled goldsmiths (see Sir W. R. Drake, Notes on Venetian Ceramics, London, 1868, privately printed). This ware was made by Saxon workmen with clay obtained from Saxony. To this factory, however, we can safely attribute the tall cup and saucer, with the arms of Benedict xiii. (1724-30), and the mark ‘Ven^a’ (Pl. d. 63), in the Franks collection (No. 446).

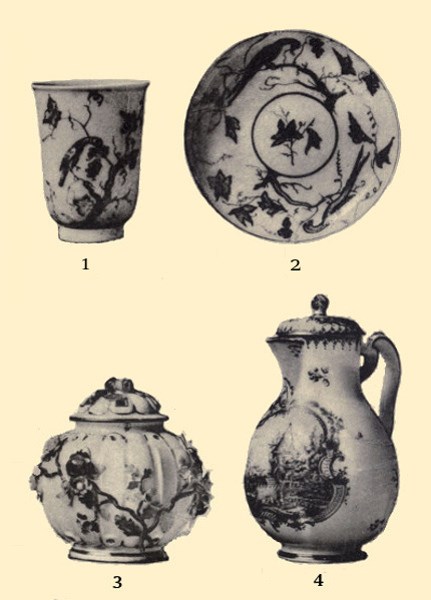

PLATE XLI. 1 AND 2—VENETIAN, BLUE AND WHITE

3—MEISSEN

4—FRANKENTHAL, LILAC AND GOLD

At this time Hunger, the Saxon painter and gilder, was in Venice. He was already back at Meissen in 1725, and Dr. Brinckmann thinks that he may have brought back from Venice the process of passing the gilding through the muffle, which about that time replaced, at Meissen, the older plan of ‘lac-gilding.’ The Vezzi works were closed in 1740, and not till 1758 do we hear of fresh attempts to imitate the Meissen ware. This time it was a Saxon family driven out from Meissen by the war, one Hewelcke and his wife, who set up a short-lived factory in which they attempted to make porcelain ‘ad uso di Sassonia.’

It was probably with the assistance of Hewelcke that Geminiano Cozzi in 1764 established the porcelain works where (as we learn from the report drawn up by the Inquisitor alle Arti a few years later) he gave employment to forty-five workmen. Cozzi made porcelain ‘ad uso di Giappone,’ much of which was exported to Trieste and the Levant.200 This ware, decorated in Oriental style, must have been made exclusively for the trade with the East, for, to judge from the specimens in our museums, it was rather the ware of Meissen than that of Imari that Cozzi took as his model. We find on his porcelain small views, especially coast-scenes and ports, outlined in black and gold; again, on tea-and coffee-services, flower-pieces and chinoiseries. He turned out also some biscuit and glazed statuettes of considerable merit. Cozzi’s factory survived until 1812. An anchor in red, larger than that used at Chelsea, and of a different shape, is the mark usually found on this china201 (Pl. d. 64).

Le Nove.—A Venetian family, the Antonibon, had early in the eighteenth century established an important manufactory of majolica at Le Nove, near Bassano. Later on they turned their attention to porcelain and, after the year 1760, Pasquale Antonibon produced some successful ware marked with a star (Pl. d. 65). One or two well modelled and carefully finished specimens of this porcelain at South Kensington show the influence of both Meissen and Sèvres. These works were in operation as late as 1825.

Vinovo.—In the royal castle of Vinovo or Vineuf, near Turin, some unsuccessful endeavours to manufacture porcelain were made with the help of one of the younger Hannongs of Strassburg. A Turin doctor, Vittore Amadeo Gioanetti, who had already made numerous experiments with the clays and rocks of the district, met with better success about 1780. The paste of this ware contains a considerable amount of silicate of magnesia, obtained from a deposit of magnesite discovered in the neighbourhood by the doctor.202 This hybrid ware is more easily fusible than a true porcelain, but it resists well rapid variations of temperature. The usual mark is the letter V surmounted by the cross of the house of Savoy (Pl. d. 66).

Capo di Monte.—Here in the northern suburbs of Naples, just beneath the Royal Palace, an important factory of soft-paste porcelain was established in 1742. Don Carlos, of Bourbon-Farnese extraction, had recently exchanged his dukedom of Parma for the throne of the Two Sicilies. In 1738 he had married a Saxon princess, but there is little sign of any German influence either in the design or composition of the ware made at his new porcelain factory at Capo di Monte. Like his cousin at Versailles at a later date, he took the keenest interest in the sale of his porcelain. An annual fair was held in front of the palace, and a large purchase there was a sure passport to the favour of the king, who is even said to have worked as a potter himself. When in 1759 Don Carlos succeeded to the throne of Spain as Charles iii., he, as it were, carried his porcelain works with him, taking away the best workmen, so that little of interest was made at Naples after that date.

To this earlier period belong the plain white pieces often in imitation of sea-shells, or again resting on a heap of smaller shells moulded probably from nature (a very similar ware was made at Bow and other English factories). We find also highly coloured statuettes and groups of figures. But the name of Capo di Monte is associated above all with another style of decoration. The surface of the ware in this case is covered by groups of figures, mythological subjects by preference, and by vegetation, moulded in low relief and delicately coloured. This was the ware imitated at Doccia in later days, and also, it would seem, at Herend, in Hungary. But perhaps the most characteristic pieces then made at Naples are the little detached figures, generally grotesques, delicately modelled and painted (Pl. xlii.).

In this Capo di Monte porcelain we may note generally the prevalence of extreme rococo forms. The glaze of the white ware has a pleasant warm tone resembling that of some of the Fukien porcelain, which may in part have served as a model.

When the factory was re-established first at Portici and then again at Naples, a very different influence is perceptible. There is a service at Windsor presented by the King of Naples to George iii. in 1787, decorated with ‘peintures Hetrusques,’ that is to say, with reproductions of antiques in the Museo Borbonico. This later ware generally bears as a mark an N surmounted by a crown.

Doccia.—The interest of the factory at Doccia, some five miles to the west of Florence, where majolica and many varieties of porcelain have been made for the last one hundred and seventy years, centres round the Ginori family. The founder of those works, the Marchese Carlo Ginori,203 who belonged to an old Florentine family, was sent, in 1737, by the Grand Duke on a diplomatic mission to the Emperor Francis i. He had already, at his villa near Sesto, succeeded in making some imitations of Oriental porcelain, and on his return from Vienna he brought back with him the arcanist Carl Wandhelein. With his assistance Ginori was able in a short time to turn out some well modelled statuettes. The paste, however, was not very white or uniform, and the larger pieces are generally disfigured by fissures. To this time belongs probably a large statuette of a crouching Venus at South Kensington. This kind of ware had its inspiration, no doubt, in the ambitious attempts to replace the works of the sculptor with which the Meissen factory was occupied about this time. Ginori was soon after appointed Governor of Leghorn,204 and he is said to have despatched a vessel to China expressly to bring back the kaolin of that country.