полная версия

полная версияPorcelain

Both M. de Fulvi and his brother died in 1751, the company was broken up, and but for the energy and influence of a certain M. Hultz, of whom nothing further is known, the manufacture would have come to an end. We must remember that on the death of the finance minister, his former enemy, Madame de Pompadour, practically took his place. Her power was at that time at its height (she ‘reigned’ from 1745 to her death in 1764), so that we may perhaps regard the M. Hultz of Bacheliers memoir as one of the favourite’s ‘ghosts.’

It was certainly the influence of the Marquise de Pompadour that induced Louis xv., in 1753, to sign the arrêt by which the title of Manufacture Royale de Porcelaine was conferred on the establishment. At the same time many important privileges were granted. The establishment was now removed to Sèvres, where a plot of ground containing some glass-works, the property of the favourite, was bought for 66,000 livres, and the new factory set up in an adjacent domain that had formerly belonged to the musician Lully. The king subscribed for a quarter of the new capital. The troubles, however, were not yet ended: the workshops were badly built and badly arranged. Finally, in 1759, Louis took over all the shares of the company, which was at that time in liquidation. A yearly grant of 96,000 livres secured the financial position. In all these arrangements we see the hand of the Pompadour, and still more in the keen way in which the business side of the establishment was pushed. At the New Year a sale took place at Versailles, in the palace. The king presided, and fixed the prices of the porcelain. A large purchase of china on these occasions was a sure way to royal favour and promotion.184

A good deal of uncertainty hangs over the nature of the early work produced at Vincennes, and no definite mark has been assigned to the factory, before the time when the permission to use the double L was granted, in 1751 or 1753. When, however, the royal cipher occurs without a year letter, there is some presumption in favour of a date previous to the latter year (Pl. d. 55).

We should infer from what Bachelier tells us that up to 1748 the designs were chiefly derived from Oriental china. But in addition the following forms and styles were in use in the pre-royal period at Vincennes:—

1. A rage for the production of artificial flowers, especially in plain white ware, existed at one time, and when the Vincennes artists were able to rival the Dresden flowers that had previously been imported, from this department alone was a steady source of income obtained. The flowers first produced were confined merely to small detached blossoms, but in 1748 M. de Fulvi presented to the queen a trophy of white porcelain which surpassed anything yet manufactured. On a base or pedestal of white ware, mounted in gilt bronze, rises a small tree completely covered with blossom of white porcelain, under which stand three female figures of the same material. The whole trophy is about three feet in height.185 So again in 1750 we hear that the king had ordered similar bouquets of flowers, ‘peintes au naturel,’ which were to cost 800,000 livres! This for the famous Château de Bellevue, and for Madame de Pompadour.186

2. Much of the porcelain made at Vincennes at this time (1740-50) was decorated with scattered groups of flowers on a white ground, a style then known as fleurs de Saxe. These flowers were often in high relief, and in this case they formed a passage to the first group.

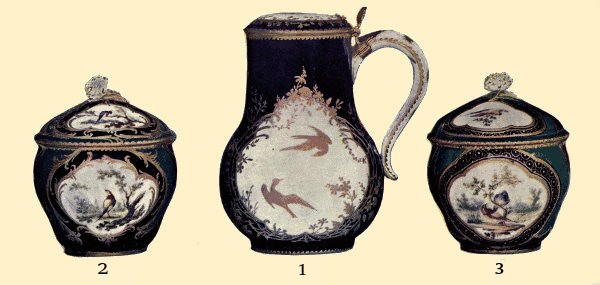

3. There exist certain small pieces, chiefly cups and saucers (of the trembleuse type, as usual at this time), with a ground of a deep blue. A great vigour and depth is given to the colour (known later as bleu du roi) by its somewhat irregular or mottled texture, a result, it is said, of the manner in which it was painted on to the biscuit (it is an underglaze colour) with a brush. We may note that the use of a dark ground for porcelain was exceptional at this time in France. This bleu de Vincennes was imitated with some success by Sprimont at Chelsea.

Gravant (he who had the secret of the paste) had before 1753, so Hellot tells us in his report, succeeded in making a paste much whiter than that of Chantilly, so as to allow of a ‘couverte crystalline et parfaitement diaphane’ in place of the opaque ‘vernix de Fayance’ (sic) used by Ciron at that factory. It is indeed important to remember that before the works were removed from Vincennes, the soft paste that we know as Sèvres had already reached its highest development both as regards the materials and the decoration. The most beautiful and characteristic colours were already used with complete mastery, and (certainly by the year 1753) the paintings of the cartels had attained a delicacy and finish never surpassed in later times,—this is at least true of certain classes of subjects, the amorini and wreaths of flowers, for instance. In proof of this I need only point to certain pieces of turquoise in the Wallace collection (Gallery xv., Case A.), above all to the soupière (No. 7), modelled, no doubt, after a silversmith’s design. If we compare such pieces to the porcelain of Saint-Cloud and Chantilly, or to the somewhat tentative work turned out at Vincennes itself but a few years earlier, it is difficult to account for this rapid advance, especially at a time of change and financial difficulties. This is certainly the most interesting period—(I mean the years just at the middle of the century)—in the whole history of French porcelain, and we must remember that the change came about precisely at the time (1751) when Madame de Pompadour’s influence became predominant.

PLATE XXXVI. SÈVRES

The free access to the royal factory—the workshops seem to have been regarded at one time as a fashionable lounge—made the preservation of any secret processes very difficult. Bachelier says that ‘on vient s’y promener comme dans les maisons royales,’ and he complains bitterly of the loss of time, the dirt, and the accidents caused by the throng of people. A succession of edicts, one as early as the year 1747, was issued, restricting the access of visitors.

When the difficulties connected with the paste and the decoration had been surmounted, a demand arose for protection against the competition of outside works. With this object a whole series of edicts, many of them of a contradictory nature, was issued between the years 1750 and 1780. Of these the special aim was to prevent or hamper the production of porcelain in other works, above all in those within a certain radius of Paris, or failing that, at least to restrict the use of colour, and especially of gilding, by such works as had to be tolerated.

At the time of the removal to Sèvres the staff consisted of more than a hundred workmen. Duplessis, the silversmith of the king, was intrusted with the modelling and with the general artistic direction, and Hellot, as we have seen, was what we should now call ‘scientific adviser.’187

Bachelier complains that the nature of the paste and glaze was unfavourable to the production of small figures, ‘luisantes et colorées,’ like those of Saxony. He claims to have been the first—this was as early as 1748—to recommend the use of white biscuit to reproduce in porcelain, among other things, ‘some of the pastoral ideas of M. Boucher,’ and this style, he tells us, ‘had a great success up to the time when M. Falconet, to whom the department was intrusted in 1757, introduced a more noble style, one more generalised and less subject to the evolution of fashion.’ Falconet was carried off to Russia in 1766, to execute for Catherine ii. the great statue of Peter the Great, and Bachelier then took his place. It was under Falconet that the best work was produced in this department, although at a later date such well-known names as Robert le Lorrain, Pajou, Clodion, Pigalle, and Houdon are found upon the books of the Sèvres works. No biscuit statuettes of pâte tendre were made after the year 1777.

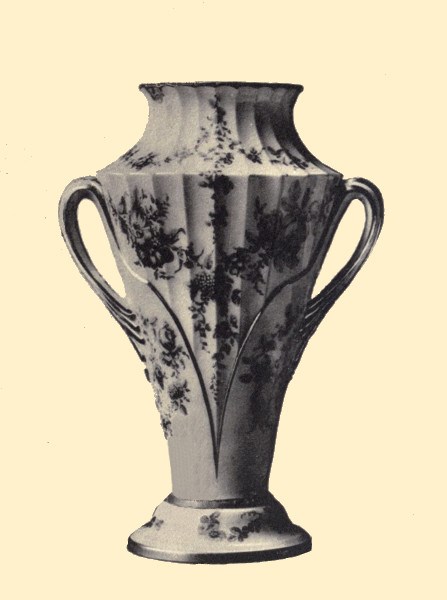

The models after which the vases and other objects were designed—and each year some fresh form was introduced—are still preserved at Sèvres. We can trace in them, as in the mountings of the contemporary furniture, the passage from the haute rocaille of the fifties to the simpler forms in favour at the beginning of the reign of Louis xvi.

PLATE XXXVII. SÈVRES PORCELAIN

The fashion of encasing the porcelain of China in metal mounts—for this the large monochrome pieces were preferred—had come in at an earlier period. The contorted forms of the gilt metal undoubtedly bring out by contrast the simple outlines and smooth surfaces of the crackle and celadon vases. In the Jones collection at South Kensington there are some superbly fine examples of this collocation of French and Chinese work. During the sixties and later it became the fashion to combine the ormolu and other kinds of metal-work with the Sèvres porcelain in many new ways, and the pendules of the time show ingenious combinations of the two materials in endless variety. It must be borne in mind that the simpler forms that we associate with the reign of Louis xvi. were already asserting themselves several years before the death of his predecessor.

If we examine the choicer pieces in any collection of Sèvres china, we find that the date-marks range within a very small interval of time—a few years on either side of 1760. This narrow limit for the best work is well exemplified both in the Jones collection and at Hertford House. We shall return to this point when describing the turquoise and rose grounds of this time.

Once established at Sèvres under direct royal patronage, the principal efforts of the staff were directed to the designing and the execution of elaborate dinner-services, destined to be presented in turn to the various crowned heads of Europe. As early as 1754 a service was made for Maria Theresa, la Reine-Impératrice. In 1758 a service with a green ground and figures, flowers, and birds in cartels was commanded by Louis xv. for presentation to the King of Denmark; in 1760 a service de table of two hundred and eighty-one pieces is presented to the Elector-Palatine Karl Theodor, the porcelain enthusiast of Frankenthal. In 1764, and again in 1772 and 1779, the Ministre d’État Bertin forwarded to the Chinese Emperor Kien-lung, through the medium of the Jesuit missionaries, presents of Sèvres porcelain.188 In 1768 and 1769 a further grand service de table, fond lapis caillouté189 is presented to the Danish king; in 1775 it is the turn of a Spanish princess, and in 1777 of the emperor. In 1778 the king sends to the Sultan of Morocco a tea-service, and at the same time presents other pieces of china to the Moorish ambassador. In the same year the Empress Catherine ordered at Sèvres the famous service of seven hundred and forty-four pieces, bleu céleste (i.e. turquoise) ground, decorated with camées incrustés. The flowers in this set were painted by Taillandier, and the gilding executed by Vincent and Le Guay. There is a plate from this service at South Kensington: on the centre the letter E, formed of minute flowers, and the Roman numeral II, stand for Ekaterina the Second. To this set belong also the three large brûle-parfums vases at Hertford House, and there are other pieces in private hands.190 The empress disputed the price (328,188 livres) demanded for the service, and a long diplomatic correspondence on the point has been preserved. M. Davillier gives some details of eight other royal services made between this time and the end of the century, among them one with green ground, for Prince Henry of Prussia (1784), of which several of the pieces were jewelled (ornées d’émaux), and in 1788 a grand service de table with vases, cups, pictures, and busts sent to Tippoo Saib, Sultan of Mysore.

PLATE XXXVIII. SÈVRES

It is usual to distinguish the different services, cabarets or garnitures, by the colour of the ground which is maintained throughout the set. Thus we find the fond lapis mentioned above and the fond vert, a peculiar shade of green very much admired at the time and often repeated in the lacquered furniture and even in the panels of a whole apartment.

We have already spoken of the Turquoise Blue, but the colour is so important that we will quote more fully the somewhat enigmatical account of it given by Hellot. ‘The bleu du roi ground, called before the Christmas fêtes of 1753 bleu ancien (Oriental turquoise by daylight, emerald or malachite by artificial light), with which his majesty has been so satisfied, is composed as follows....’ We are then told that we should purchase at the Sieur Moniac, in the Rue Quincampoise, opposite to, etc.;—but it is needless to follow these details—in fact I only quote a few words as a sample of Hellot’s innumerable recipes for colours. This blue enamel, for it is an enamel, and not painted sous couverte like the old Vincennes blue, is composed of ‘aigue-marine’ (some preparation of copper) three parts, Gravant’s glaze one part, and of minium one and a third parts. The ingredients are melted together, à très grand feu, and the resultant glass finely powdered. ‘This powder is dusted through a silk sieve, upon the mordant that has been applied to the surface of the already glazed porcelain. The piece is then heated in the “painter’s stove” (the muffle). The first layer of colour comes out sometimes crackled, and always irregular (mal unie). To make the enamel uniform, the piece is again coated and again passed through the painter’s stove.’ Not only the strength and quality of the enamel, but its tint also, vary much, even in pieces dating from the best period; some examples tend more to green than others. In the more brilliant and intense examples of the bleu céleste, to give the colour its old or one of its old names, the ground on close examination appears to be more or less mottled, darker clots, as it were, floating about in a lighter medium. Indeed some such ‘texture’ seems to be necessary to bring out the full effect and brilliancy in the case of other glazes and transparent enamels on porcelain, and to its absence the dull and ‘uninteresting’ aspect of much of our modern porcelain may be attributed.

Rose Pompadour.—We have seen that the various shades of pink derived from gold (see the note on p. 284) had for some time been used in the decoration of porcelain, but that the recipes for them were regarded as precious trade secrets. The rose carnée, or Pompadour191 (often wrongly called rose du Barry), belongs to this class. The credit of its first successful employment as a uniform ground-colour is probably due to the chemist Hellot.192 This colour was in use at Sèvres for only a short period of years, say between 1753 and 1763. The dated specimens in the Wallace collection range between 1754 and 1759. One is almost tempted to associate its sudden disappearance with some whim of Madame de Pompadour; perhaps having in her possession nearly all that had been made, she wished to ‘corner the market.’ The manufacture seems to have ceased before her death (1764), and afterwards the secret was lost. The rose carnée ground is often associated with one of apple-green, but the combination is not a very pleasing one.

PLATE XXXIX. SÈVRES

Great attention has always been paid to the Gilding at Sèvres. When applied heavily to the handles and feet of vases, it replaces, in some measure, the ormolu mounts. So, when surrounding the little pictures painted on the cartels of vases and bowls, or on the centre of plates, this gilding represents in position and design the gold frame of the period. At the time of the reorganisation of the works in 1753 we find, along with Bachelier and Duplessis, a certain Frère Hippolyte, a Benedictine monk, mentioned as the possessor of secret processes of gilding, and he was well paid for his periodical visits to the works. Bachelier, writing in 1781, has a note protesting against the excessive employment of gold. The prohibition of its use at other porcelain factories at this time was based, he says, on ‘economic grounds,’ that the metal might not be lost for commerce. ‘This enormous expenditure of gold,’ he protests, ‘is the more revolting, inasmuch as it is in bad taste.’ Bachelier distinguishes the ‘or bruni en effet’ from the ‘or bruni en totalité.’ By the use of the first, in opposition both to the unburnished and to the plain polished gold, it was intended to imitate chiselled metal (the ormolu mounts), and this method of burnishing, we are told, should be confined to large vases which are not subjected to any wear and tear by cleaning or otherwise. The gold, in all cases, was simply sprinkled on without the admixture of any flux, and the burnishing was carried out chiefly by women in a special department of the works. This burnishing was effected au clou, that is, by means of a stump of iron inserted at the end of a stick. Agate burnishers were not introduced till a later period. Great pressure was required in the earlier method, resulting in deeply incised lines, and there is less uniformity of surface than where the agate is used.

The Jewelled Sèvres has never found much favour in France, and the only name the French have for this decoration—porcelaine ornée d’émaux—is not very distinctive. A transparent, glassy, or sometimes an opaque enamel of very brilliant tint is applied in the form of little beads standing out in relief and set in gold mountings. This application of ‘appliqués gems in chased gold setting,’ unless used with great delicacy and moderation, produces a tawdry and overloaded effect, above all when applied upon coloured grounds. But when these little ‘paste-jewels’ are set upon the soft white of the Sèvres pâte tendre the result is sometimes very pleasing. On a cup and saucer belonging to Mr. Currie, now at South Kensington, the ruby and turquoise jewels are connected by branches of gold overlaid with a transparent green enamel (Pl. xl.). On the other hand, on a large ewer and basin of turquoise, with a decoration of gold, in the ‘Londonderry Cabinet’ at Hertford House, which has the date-letter for 1768, the original design is capriciously overlaid by a series of jewelled chains which (if we are to trust the date-mark on the ewer) must certainly have been added at a later time. Indeed the manufacture of this jewelled ware seems to have been confined to the years 1780-86.

When a school of painting was first established at Sèvres, it was to the fan-painters and to the miniature-painters in enamel that Bachelier turned for assistance, and we can detect the mannerisms peculiar to these two schools in the decoration of some of the earlier pieces made at Sèvres.

Marks.—By the royal decree of 1753, from which we have already quoted, it was ordered that all pieces should be marked with the well-known royal cipher, the double L, and that a letter-mark indicating the year should be added (Pl. d. 56). The single letters of the alphabet carry us from 1753 to 1776; after that double letters were used till 1793, when the king’s initial was replaced by the letters R. F., with the addition of the word Sèvres. A mark of this latter kind was in use till the end of the century, after which time no more soft paste was made.

PLATE XL. JEWELLED SÈVRES

Each artist marked his work with a monogram or a private sign, often suggested by a play upon the syllables of his name, as in the case of the canting arms of heraldry. For example, ‘2000’ (vingtcents) was adopted by Vincent, the famous gilder; a branch of a tree by Dubois; and, more strangely still, a triangle, the sign of the Trinity, by an artist named Dieu. These marks were placed underneath, or by the side of, the royal cipher. The marks of more than a hundred artists have been identified from the records kept at Sèvres—painters of flowers, garlands, landscapes, marines, genre-subjects, and finally gilders. A complete list of these men, with their marks, may be found in Garnier, Chaffers, and other writers on the subject.

The manufacture of true kaolinic porcelain was begun in 1769, but the soft paste continued to be made for another thirty years, side by side with the new ware. It was not till the year 1804 that it was finally abandoned by Brongniart, the new director. He found the soft-paste ware unsuitable for the big pieces now ordered by the Imperial Government. The paste was difficult to work, the preparation was expensive, and the dust formed both from the paste and from the lead glaze was injurious to the health of the workmen. One or two attempts have since been made at Sèvres to revive the old ware, but they have fallen through in every case.

Brongniart, in 1804, to provide funds for the impoverished works and to pay the arrears of wages to the workmen, threw on the market the large stock of plain white soft paste that had accumulated in the magazine. Now at that time there were in Paris many skilled porcelain painters, some of them ex-employés at Sèvres, and others, men who made a living by painting on the plain ware sent from Limoges and other factories. These ‘chambrelans’ (they painted at home, en chambre, and corresponded to our English ‘chamberers’) were now employed by the dealers who had eagerly bought up the ware that Brongniart had parted with.193 They painted and gilt this white ware in imitation of the Sèvres porcelain of the best period so successfully that the services they turned out have found their way into royal collections. This ware, in fact, forms a group by itself, quite apart from the later imitations of the pâte tendre, which, in every degree of merit and demerit, are now found in the china-shops of Europe and America. M. Garnier points out three signs by which this pseudo-Sèvres may be recognised: 1. The green prepared from the newly introduced chromium is of a warm yellowish tint, and displays none of the submetallic tints so often to be seen in enamels coloured by copper, as in the famille verte of China. 2. The gold on this bastard ware, burnished with an agate polisher, differs in quality of surface from the old gilding worked au clou. 3. The date-marks and painters’ monograms were copied at hazard from the old pieces—at that time no list of these marks had been made public—so that, for example, the monogram of a gilder may be found on a piece decorated in colours only.

CHAPTER XVIII

THE HARD-PASTE PORCELAIN OF SÈVRES AND PARIS

THE soft paste of Sèvres, even during the period of the fifties and sixties, when the most exquisite ware was being made, seems always to have been regarded somewhat as a make-shift, to be employed until the materials for making a true porcelain should be discovered in France. For it was the ignorance of the true nature of kaolin, and where to look for it, that so fortunately delayed its introduction at Sèvres. As early as the Vincennes days, one of the Hannongs of Strassburg had offered to sell his secret, and this offer was repeated at a later time by himself and by his son. At Sèvres, before 1760, two German workmen were retained to teach the Saxon process, but the materials had still to be obtained from Germany.

Meantime Macquer, who had succeeded to the post of scientific adviser on the death of Hellot, had been experimenting on his own account, and above all encouraging others to search for the precious white earth within French territory. At length, in 1760, some samples were sent from Alençon, from which a true porcelain was made, but of poor quality and of a grey colour. Outside the Sèvres works the younger Hannong had set up a factory at Vincennes, and the Comte de Brancas Lauraguais, whom we shall meet with again in England, had by 1764 begun his experiments and his search after deposits of kaolin. There still exist a few portrait-medallions moulded in hard porcelain, which, on the ground of the letters B. L. engraved on the back, have been attributed to that energetic nobleman.