полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 10, No. 60, October, 1862

General Wilkinson wrote from Fort George, Sept. 16, 1813: "We count, on paper, 4,600, and could show 3,400 combatants"; that is, 25 per cent, and more are sick. "The enemy, from the best information we have, have about 3,000 on paper, of whom 1,400," or 46.6 per cent., "are sick."30

MEXICAN WAR

There was a similar waste of life among our troops in the Mexican War. There is no published record of the number of the sick, nor of their diseases. But the letters of General Scott and General Taylor to the Secretary of War show that the loss of effective force in our army was at times very great by sickness in that war.

General Scott wrote:—

"Puebla, July 25, 1847.

"May 30, the number of sick here was 1,017, of effectives 5,820."

"Since the arrival of General Pillow, we have effectives (rank and file) 8,061, sick 2,215, beside 87 officers under the latter head."31

Again:—

"Mexico, Dec. 5,1847.

"The force at Chapultepec fit for duty is only about 6,000, rank and file; the number of sick, exclusive of officers, being 2,041."32

According to these statements, the proportions of the sick were 17.4 to 27.4 and 24.7 per cent of all in these corps at the times specified.

General Taylor wrote:—

"Camp near Monterey, July 27,1847.

"Great sickness and mortality have prevailed among the volunteer troops in front of Saltillo."33

August 10th, he said, that "nearly 23 per cent, of the force present was disabled by disease."

The official reports show only the number that died, but make no distinction as to causes of death, except to separate the deaths from wounds received in battle from those from other causes.

During that war, 100,454 men were sent to Mexico from the United States. They were enlisted for various periods, but served, on an average, thirteen months and one day each, making a total of 109,104 years of military service rendered by our soldiers in that war. The total loss of these men was 1,549 killed in battle or died of wounds, 10,986 died from diseases, making 12,535 deaths. Besides these, 12,252 were discharged for disability. The mortality from disease was almost equal to the annual rate of 11 per cent., which is about ten times as great as that of men in ordinary civil life at home.

SICKNESS IN THE PRESENT UNION ARMY

There are not as yet, and for a long time there cannot be, any full Government reports of the amount and kind of sickness in the present army of the United States. But the excellent reports of the inquiries of the Sanitary Commission give much important and trustworthy information in respect to these matters. Most of the encampments of all the corps have been examined by their inspectors; and their returns show, that the average number sick, during the seven months ending with February last, was, among the troops who were recruited in New England 74.6, among those from the Middle States 56.6, and, during six months ending with January, among those from the Western States 104.3, in 1,000 men. From an examination of 217 regiments, during two months ending the middle of February, the rate of sickness among the troops in the Eastern Sanitary Department was 74, in the Central Department, Western Virginia and Ohio, 90, and in the Western, 107, in 1,000 men. The average of all these regiments was 90 in 1,000. The highest rate in Eastern Virginia was 281 per 1,000, in the Fifth Vermont; and the lowest, 9, in the Seventh Massachusetts. In the Central Department the highest was 260, in the Forty-First Ohio; and the lowest, 17, in the Sixth Ohio. In the Western Department the highest was 340, in the Forty-Second Illinois; and the lowest, 15, in the Thirty-Sixth Illinois.

On the 22d of February, the number of men sick in each 1,000, in the several divisions of the Army of the Potomac, was ascertained to be,—

Keyes's, 30.3

Sedgwick's, 32.0

Hooker's, 43.7

McCall's 44.4

Banks's, 45.0

Porter's, 46.4

Blenker's, 47.7

McDowell's, 48.2

Heintzelman's 49.0

Franklin's 54.1

Dix's, 71.8

United States Regulars, 76.0

Sumner's, 77.5

Smiths's, 81.6

Casey's 87.634

Probably there has been more sickness in all the armies, as they have gone farther southward and the warm season has advanced. This would naturally be expected, and the fear is strengthened by the occasional reports in the newspapers. Still, taking the trustworthy reports herein given, it is manifest that our Union army is one of the healthiest on record; and yet their rate of sickness is from three to five times as great as that of civilians of their own ages at home. Unquestionably, this better condition of our men is due to the better intelligence of the age and of our people,—especially in respect to the dangers of the field and the necessity of proper provision on the part of the Government and of self-care on the part of the men,—to the wisdom, labors, and comprehensive watchfulness of the Sanitary Commission, and to the universal sympathy of the men and women of the land, who have given their souls, their hands, and their money to the work of lessening the discomforts and alleviating the sufferings of the Army of Freedom.

OTHER LIGHTER AND UNRECORDED SICKNESS

The records and reports of the sickness in the army do not include all the depreciations and curtailments of life and strength among the soldiers, nor all the losses of effective force which the Government suffers through them, on account of disease and debility. These records contain, at best, only such ailments as are of sufficient importance to come under the observation of the surgeon. But there are manifold lighter physical disturbances, which, though they neither prostrate the patient, nor even cause him to go to the hospital, yet none the less certainly unfit him for labor and duty. Of the regiment referred to by Dr. Mann, and already adduced in this article, in which 700 were unable to attend to duty, 340 were in the hospital under the surgeon's care, and 360 were ill in camp. It is probable that a similar, though smaller, discrepancy often exists between the surgeon's records and the absentees from parades, guard-duty, etc.

It is improbable, and even impossible, that complete records and reports should always be made of all who are sick and unfit for duty, or even of all who come under the surgeon's care. Sir John Hall, principal Medical Officer of the British army in the Crimea, says that there were "218,952 admissions into hospital."35 "The general return, showing the primary admissions into the hospitals of the army in the East, from the 10th April, 1854, to the 30th June, 1856, gives only 162,123 cases of all kinds."36 But another Government Report states the admissions to be 162,073.37 Miss Nightingale says, "There was, at first, no system of registration for general hospitals, for all were burdened with work beyond their strength."38 Dr. Mann says, that, in the War of 1812, "no sick-records were found in the hospital at Burlington," one of the largest depositories of the sick then in the country. "The hospital-records on the Niagara were under no order."39 It could hardly have been otherwise. The regimental hospitals then, as frequently must be the case in war, were merely extemporized shelters, not conveniences. They were churches, houses, barns, shops, sheds, or any building that happened to be within reach, or huts, cabins, or tents suddenly created for the purpose. In these all the surgeons' time, energy, and resources were expended in making their patients comfortable, in defending them from cold and storm, or from suffering in their crowded rooms or shanties. They were obliged to devote all their strength to taking care of the present. They could take little account of the past, and were often unable to make any record for the future. They could not do this for those under their own immediate eye in the hospital; much less could they do it for those who remained in their tents, and needed little or no medical attention, but only rest. Moreover, the exposures and labors of the campaign sometimes diminish the number and force of the surgeons as well as of the men, and reduce their strength at the very moment when the greatest demand is made for their exertions. Dr. Mann says, "The sick in the hospital were between six and seven hundred, and there were only three surgeons present for duty." "Of seven surgeons attached to the hospital department, one died, three were absent by reason of indisposition, and the other three were sick."40 Fifty-four surgeons died in the Russian army in Turkey in the summer of 1828. "At Brailow, the pestilence spared neither surgeons nor nurses."41 Sir John Hall says, "The medical officers got sick, a great number went away, and we were embarrassed." "Thirty per cent. were sometimes sick and absent" from their posts in the Crimea.42 Seventy surgeons died in the French army in the same war. It is not reasonable, then, to suppose that all or nearly all the cases of sickness, whether in hospital or in camp, can be recorded, especially at times when they are the most abundant.

Nor do the cases of sickness of every sort, grave and light, recorded and unrecorded, include all the depressions of vital energy and all the suspensions and loss of effective force in the army. Whenever any general cause of depression weighs upon a body of men, as fatigue, cold, storm, privation of food, or malaria, it vitiates the power of all, in various degrees and with various results; the weak and susceptible are sickened, and all lose some force and are less able to labor and attend to duty. No account is taken, none can be taken, of this discount of the general force of the army; yet it is none the less a loss of strength, and an impediment to the execution of the purposes of the Government.

INVALIDING

The loss of force by death, by sickness in hospital and camp, and by temporary depression, is not all that the army is subject to. Those who are laboring under consumption, asthma, epilepsy, insanity, and other incurable disorders, and those whose constitutions are broken, or withered and reduced below the standard of military requirement, are generally, and by some Governments always, discharged. These pass back to the general community, where they finally die. By this process the army is continually sifting out its worst lives, and at the same time it fills their places with healthy recruits. It thus keeps up its average of health and diminishes its rate of mortality; but the sum and the rates of sickness and mortality in the community are both thereby increased.

During the Crimean War, 17.34 per cent, were invalided and sent home from the British army, and 21 per cent, from the French army, as unable to do military service. By this means, 11,99443 British and 65,06944 French soldiers were lost to their Governments. The army of the United States, in the Mexican War, discharged and sent home 12,252 men, or 12 per cent, of the entire number engaged in that war, on account of disability.

The causes of this exhaustion of personal force are manifold and various, and so generally present that the number and proportion of those who are thus hopelessly reduced below the degree of efficient military usefulness, in the British army, has been determined by observation, and the Government calculates the rate of the loss which will happen in this way, at any period of service. Out of 10,000 men enlisted in their twenty-first year, 718 will be invalided during the first quinquennial period, or before they pass their twenty-fifth year, 539 in the second, 673 in the third, and 854 in the fourth,—making 2,784, or more than one-quarter of the whole, discharged for disability or chronic ailment, before they complete their twenty years of military service and their forty years of life.

It is further to be considered, that, during these twenty years, the numbers are diminishing by death, and thus the ratio of enfeebled and invalided is increased. Out of 10,000 soldiers who survive and remain in the army in each successive quinquennial period, 768 will be invalided in the first, 680 in the second, 1,023 in the third, and 1,674 in the fourth. In the first year the ratio is 181, in the fifth 129, in the tenth 165, in the fifteenth 276, and in the twentieth 411, among 10,000 surviving and remaining.

The depressing and exhaustive force of military life on the soldiers is gradually accumulative, or the power of resistance gradually wastes, from the beginning to the end of service. There is an apparent exception to this law in the fact, that, in the British army, the ratio of those who were invalided was 181 in 10,000, but diminished, in the second, third, and fourth years, to 129 in the fifth and sixth, then again rose, through all the succeeding years, to 411 in the twentieth. The experience of the British army, in this respect, is corroborated by that of ours in the Mexican War. From the old standing army 502, from the additional force recently enlisted 548, and from the volunteers 1,178, in 10,000 of each, were discharged on account of disability. Some part of this great difference between the regulars and volunteers is doubtless due to the well-known fact, that the latter were originally enlisted, in part at least, for domestic trainings, and not for the actual service of war, and therefore were examined with less scrutiny, and included more of the weaker constitutions.

The Sanitary Commission, after inspecting two hundred and seventeen regiments of the present army of the United States, and comparing the several corps with each other in respect of health, came to a similar conclusion. They found that the twenty-four regiments which had the least sickness had been in service one hundred and forty days on an average, and the twenty-four regiments which had the most sickness had been in the field only one hundred and eleven days. The Actuary adds, in explanation,—"The difference between the sickness of the older and newer regiments is probably attributable, in part, to the constant weeding out of the sickly by discharges from the service. The fact is notorious, that medical inspection of recruits, on enlistment, has been, as a rule, most imperfectly executed; and the city of Washington is constantly thronged with invalids awaiting their discharge-papers, who at the time of their enlistment were physically unfit for service."45 In addition to this, it must be remembered, that, although all recruits are apparently perfect in form and free from disease when they enter the army, yet there may be differences in constitutional force, which cannot be detected by the most careful examiners. Some have more and some have less power of endurance. But the military burden and the work of war are arranged and determined for the strongest, and, of course, break down the weak, who retire in disability or sink in death.

GENERAL VITAL DEPRESSION

Two causes of depression operate, to a considerable degree in peace and to a very great degree in war, on the soldier, and reduce and sicken him more than the civilian. His vital force is not so well sustained by never-failing supplies of nutritious and digestible food and regular nightly sleep, and his powers are more exhausted in hardships and exposures, in excessive labors and want of due rest and protection against cold and heat, storms and rains. Consequently the army suffers mostly from diseases of depression,—those of the typhoid, adynamic, and scorbutic types. McGrigor says, that, in the British army in the Peninsula, of 176,007 cases treated and recorded by the surgeons, 68,894 were fevers, 23,203 diseases of the bowels, 12,167 ulcers, and 4,027 diseases of the lungs.46 In the British hospitals in the Crimean War, 39 per cent. were cholera, dysentery, and diarrhoea, 19 per cent. fevers, 1.2 per cent. scurvy, 8 per cent. diseases of the lungs, 8 per cent. diseases of the skin, 3.3 per cent. rheumatism, 2.5 per cent. diseases of the brain and nervous system, 1.4 per cent. frost-bite or mortification produced by low vitality and chills, 13, or one in 12,000, had sunstroke, 257 had the itch, and 68 per cent. of all were of the zymotic class,47 which are considered as principally due to privation, exposure, and personal neglect. The deaths from these classes of causes were in a somewhat similar proportion to the mortality from all stated causes,—being 58 per cent. from cholera, dysentery, and diarrhoea, and 1 per cent. from all other disorders of the digestive organs, 19 per cent. from fevers, 3.6 per cent. from diseases of the lungs, 1.3 per cent. from rheumatism, 1.3 per cent. from diseases of the brain and nervous system, and 79 per cent. from those of the zymotic class. The same classes of disease, with a much larger proportion of typhoid, pneumonia, prostrated and destroyed many in the American army in the War of 1812.

In paper No. 40, p. 54, of the Sanitary Commission, is a report of the diseases that occurred in forty-nine regiments, while under inspection about forty days each, between July and October, 1861. 27,526 cases were reported; of these 67 per cent. were zymotic, 41 per cent. diseases of the digestive organs, 22 per cent. fevers 7 per cent. diseases of the lungs, 5 per cent. diseases of the brain. Among males of the army-ages the proportions of deaths from these classes of causes to those from all causes were, in Massachusetts, in 1859, zymotic 15 per cent., diseases of digestive organs 3.6 per cent., of lungs 50 per cent., fevers 9 per cent., diseases of brain 4.6 per cent48. According to the mortality-statistics of the seventh census of the United States, of the males between the ages of twenty and fifty, in Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, whose deaths in the year ending June 1st, 1850, and their causes, were ascertained and reported by the marshals, 34.3 per cent. died of zymotic diseases, 8 per cent. of all the diseases of the digestive organs, 30.8 per cent. of diseases of the respiratory organs, 24.4 per cent. of fevers, and 5.7 per cent. of disorders of the brain and nervous system. In England and Wales, in 1858, these proportions were, zymotic 14 per cent., fevers 8 per cent., diseases of digestive organs 7.9 per cent., of lungs 8 per cent., and of the brain 7 per cent49.

If, however, we analyze the returns of mortality in civil life, and distinguish those of the poor and neglected dwellers in the crowded and filthy lanes and alleys of cities, whose animal forces are not well developed, or are reduced by insufficient and uncertain nutrition, by poor food or bad cookery, by foul air within and stenchy atmosphere without, by imperfect protection of house and clothing, we shall find the same diseases there as in the army. Wherever the vital forces are depressed, there these diseases of low vitality happen most frequently and are most fatal.

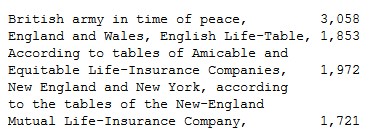

Volumes of other facts and statements might be quoted to show that military service is exhaustive of vital force more than the pursuits of civil life. It is so even in time of peace, and it is remarkably so in time of war. Comparing the English statements of the mortality in the army with the calculations of the expectation of life in the general community, the difference is at once manifest.

Of 10,000 men at the age of twenty, there will die before they complete their fortieth year,—

DANGERS IN LAND-BATTLES

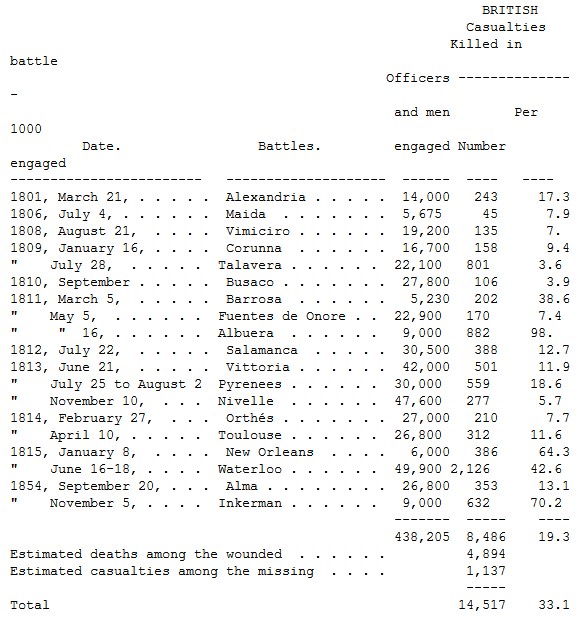

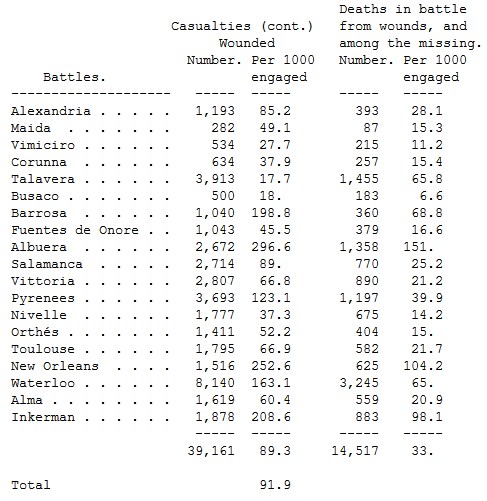

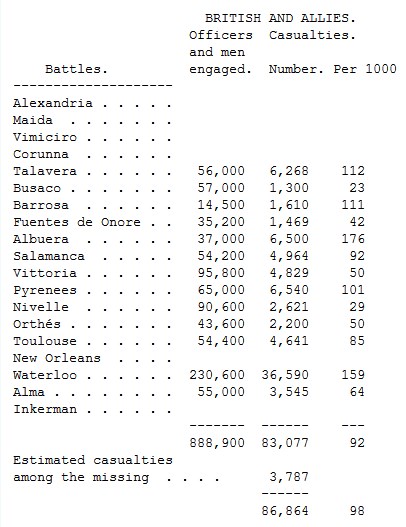

This large amount of disease and mortality in the army arises not from the battle-field, but belongs to the camp, the tent, the barrack, the cantonment; and it is as certain, though not so great, in time of peace, when no harm is inflicted by the instruments of destruction, as in time of war. The battle, which is the world's terror, is comparatively harmless. The official histories of the deadly struggles of armies show that they are not so wasteful of life as is generally supposed. Mr. William Barwick Hodge examined the records and despatches in the War-Office in London, and from these and other sources prepared an exceedingly valuable and instructive paper on "The Mortality arising from Military Operations," which was read before the London Statistical Society, and printed in the nineteenth volume of the Society's journal. Some of the tables will be as interesting to Americans as to Englishmen. On the following page is a tabular view, taken from this work, of the casualties in nineteen battles fought by the British armies with those of other nations.

TABLE 1.–NINETEEN LAND-BATTLES.

TABLE 1.–NINETEEN LAND-BATTLES. (cont.)

BRITISH. (cont.)

TABLE 1.–NINETEEN LAND-BATTLES. (cont.)

Of those who were engaged in these nineteen battles one in 51.6, or 1.93 per cent., were killed. The deaths in consequence of the battles, including both those who died of wounds and those that died among the missing, were one in 30, or 3.3 per cent. of all who were in the fight. It is worth noticing here, that the British loss in the Battle of New Orleans was larger than in any other battle here adduced, except in that of Albuera, in Spain, with the French, in 1811.

In the British army, from 1793 to 1815, including twenty-one years of war, and excluding 1802, the year of peace, the number of officers varied from 3,576 in the first year to 13,248 in 1813, and the men varied from 74,500 in 1793 to 276,000 in 1813, making an annual average of 9,078 officers and 189,200 men, and equal to 199,727 officers and 4,168,500 men serving one year. During these twenty-one years of war, among the officers 920 were killed and 4,685 were wounded, and among the men 15,392 were killed and 65,393 were wounded. This is an annual average of deaths from battle of 460 officers and 369 men, and of wounded 2,340 officers and 1,580 men, among 100,000 of each class. Of the officers less than half of one per cent., or 1 in 217, were killed, and a little more than two per cent., or 1 in 42, were wounded; and among the men a little more than a third of one per cent., 1 in 271, were killed, and one and a half per cent., 1 in 63, wounded, in each year. The comparative danger to the two is, of death, 46 officers to 37 men, and of wounds, 234 officers to 158 men. A larger proportion of the officers than of the soldiers were killed and wounded; yet a larger proportion of the wounded officers recovered. This is attributed to the fact that the officers were injured by rifle-balls, being picked out by the marksmen, while the soldiers were injured by cannon- and musket-balls and shells, which inflict more deadly injuries.

DANGERS IN NAVAL BATTLES

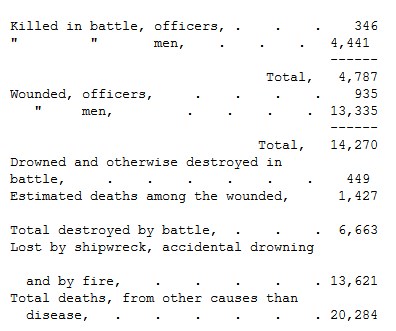

It may not be out of place here to show the dangers of naval warfare, which are discussed at length by Mr. Hodge, in a very elaborate paper in the eighteenth volume of the Statistical Society's journal. From one of his tables, containing a condensed statistical history of the English navy, through the wars with France, 1792–1815, the following facts are gathered.

During those wars, the British Parliament, in its several annual grants, voted 2,527,390 men for the navy. But the number actually in the service is estimated not to have exceeded 2,424,000 in all, or a constant average force of 110,180 men. Within this time these men fought five hundred and seventy-six naval battles, and they were exposed to storms, to shipwreck, and to fire, in every sea. In all these exposures, the records show that the loss of life was less than was suffered by the soldiers on the land. There were—

Comparing the whole number of men in the naval service, during this period, with the mortality from causes incidental to the service, the average annual loss was—