полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 10, No. 60, October, 1862

You find similar old churches and villages in all the neighboring country, at the distance of every two or three miles; and I describe them, not as being rare, but because they are so common and characteristic. The village of Whitnash, within twenty minutes' walk of Leamington, looks as secluded, as rural, and as little disturbed by the fashions of to-day, as if Doctor Jephson had never developed all those Parades and Crescents out of his magic well. I used to wonder whether the inhabitants had ever yet heard of railways, or, at their slow rate of progress, had even reached the epoch of stage-coaches. As you approach the village, while it is yet unseen, you observe a tall, overshadowing canopy of elm-tree tops, beneath which you almost hesitate to follow the public road, on account of the remoteness that seems to exist between the precincts of this old-world community and the thronged modern street out of which you have so recently emerged. Venturing onward, however, you soon find yourself in the heart of Whitnash, and see an irregular ring of ancient rustic dwellings surrounding the village-green, on one side of which stands the church, with its square Norman tower and battlements, while close adjoining is the vicarage, made picturesque by peaks and gables. At first glimpse, none of the houses appear to be less than two or three centuries old, and they are of the ancient, wooden-framed fashion, with thatched roofs, which give them the air of birds' nests, thereby assimilating them closely to the simplicity of Nature.

The church-tower is mossy and much gnawed by time; it has narrow loop-holes up and down its front and sides, and an arched window over the low portal, set with small panes of glass, cracked, dim, and irregular, through which a bygone age is peeping out into the daylight. Some of those old, grotesque faces, called gargoyles, are seen on the projections of the architecture. The church-yard is very small, and is encompassed by a gray stone fence that looks as ancient as the church itself. In front of the tower, on the village-green, is a yew-tree of incalculable age, with a vast circumference of trunk, but a very scanty head of foliage; though its boughs still keep some of the vitality which perhaps was in its early prime when the Saxon invaders founded Whitnash. A thousand years is no extraordinary antiquity in the lifetime of a yew. We were pleasantly startled, however, by discovering an exuberance of more youthful life than we had thought possible in so old a tree; for the faces of two children laughed at us out of an opening in the trunk, which had become hollow with long decay. On one side of the yew stood a framework of worm-eaten timber, the use and meaning of which puzzled me exceedingly, till I made it out to be the village-stocks: a public institution that, in its day, had doubtless hampered many a pair of shank-bones, now crumbling in the adjacent church-yard. It is not to be supposed, however, that this old-fashioned mode of punishment is still in vogue among the good people of Whitnash. The vicar of the parish has antiquarian propensities, and had probably dragged the stocks out of some dusty hiding-place, and set them up on their former site as a curiosity.

I disquiet myself in vain with the effort to hit upon some characteristic feature, or assemblage of features, that shall convey to the reader the influence of hoar antiquity lingering into the present daylight, as I so often felt it in these old English scenes. It is only an American who can feel it; and even he begins to find himself growing insensible to its effect, after a long residence in England. But while you are still new in the old country, it thrills you with strange emotion to think that this little church of Whitnash, humble as it seems, stood for ages under the Catholic faith, and has not materially changed since Wickcliffe's days, and that it looked as gray as now in Bloody Mary's time, and that Cromwell's troopers broke off the stone noses of those same gargoyles that are now grinning in your face. So, too, with the immemorial yew-tree: you see its great roots grasping hold of the earth like gigantic claws, clinging so sturdily that no effort of time can wrench them away; and there being life in the old tree, you feel all the more as if a contemporary witness were telling you of the things that have been. It has lived among men, and been a familiar object to them, and seen them brought to be christened and married and buried in the neighboring church and church-yard, through so many centuries, that it knows all about our race, so far as fifty generations of the Whitnash people can supply such knowledge. And, after all, what a weary life it must have been for the old tree! Tedious beyond imagination! Such, I think, is the final impression on the mind of an American visitor, when his delight at finding something permanent begins to yield to his Western love of change, and he becomes sensible of the heavy air of a spot where the forefathers and foremothers have grown up together, intermarried, and died, through a long succession of lives, without any intermixture of new elements, till family features and character are all run in the same inevitable mould. Life is there fossilized in its greenest leaf. The man who died yesterday or ever so long ago walks the village-street to-day, and chooses the same wife that he married a hundred years since, and must be buried again to-morrow under the same kindred dust that has already covered him half a score of times. The stone threshold of his cottage is worn away with his hob-nailed footsteps, scuffling over it from the reign of the first Plantagenet to that of Victoria. Better than this is the lot of our restless countrymen, whose modern instinct bids them tend always towards "fresh woods and pastures new." Rather than such monotony of sluggish ages, loitering on a village-green, toiling in hereditary fields, listening to the parson's drone lengthened through centuries in the gray Norman church, let us welcome whatever change may come,—change of place, social customs, political institutions, modes of worship,—trusting, that, if all present things shall vanish, they will but make room for better systems, and for a higher type of man to clothe his life in them, and to fling them off in turn.

Nevertheless, while an American willingly accepts growth and change as the law of his own national and private existence, he has a singular tenderness for the stone-incrusted institutions of the mother-country. The reason may be (though I should prefer a more generous explanation) that he recognizes the tendency of these hardened forms to stiffen her joints and fetter her ankles, in the race and rivalry of improvement. I hated to see so much as a twig of ivy wrenched away from an old wall in England. Yet change is at work, even in such a village as Whitnash. At a subsequent visit, looking more critically at the irregular circle of dwellings that surround the yew-tree and confront the church, I perceived that some of the houses must have been built within no long time, although the thatch, the quaint gables, and the old oaken framework of the others diffused an air of antiquity over the whole assemblage. The church itself was undergoing repair and restoration, which is but another name for change. Masons were making patchwork on the front of the tower, and were sawing a slab of stone and piling up bricks to strengthen the side-wall, or enlarge the ancient edifice by an additional aisle. Moreover, they had dug an immense pit in the church-yard, long and broad, and fifteen feet deep, two-thirds of which profundity were discolored by human decay and mixed up with crumbly bones. What this excavation was intended for I could nowise imagine, unless it were the very pit in which Longfellow bids the "Dead Past bury its Dead," and Whitnash, of all places in the world, were going to avail itself of our poet's suggestion. If so, it must needs be confessed that many picturesque and delightful things would be thrown into the hole, and covered out of sight forever.

The article which I am writing has taken its own course, and occupied itself almost wholly with country churches; whereas I had purposed to attempt a description of some of the many old towns—Warwick, Coventry, Kenilworth, Stratford-on-Avon—which lie within an easy scope of Leamington. And still another church presents itself to my remembrance. It is that of Hatton, on which I stumbled in the course of a forenoon's ramble, and paused a little while to look at it for the sake of old Doctor Parr, who was once its vicar. Hatton, so far as I could discover, has no public-house, no shop, no contiguity of roofs, (as in most English villages, however small,) but is merely an ancient neighborhood of farm-houses, spacious, and standing wide apart, each within its own precincts, and offering a most comfortable aspect of orchards, harvest-fields, barns, stacks, and all manner of rural plenty. It seemed to be a community of old settlers, among whom everything had been going on prosperously since an epoch beyond the memory of man; and they kept a certain privacy among themselves, and dwelt on a cross-road at the entrance of which was a barred gate, hospitably open, but still impressing me with a sense of scarcely warrantable intrusion. After all, in some shady nook of those gentle Warwickshire slopes there may have been a denser and more populous settlement, styled Hatton, which I never reached.

Emerging from the by-road, and entering upon one that crossed it at right angles and led to Warwick, I espied the church of Doctor Parr. Like the others which I have described, it had a low stone tower, square, and battlemented at its summit: for all these little churches seem to have been built on the same model, and nearly at the same measurement, and have even a greater family-likeness than the cathedrals. As I approached, the bell of the tower (a remarkably deep-toned bell, considering how small it was) flung its voice abroad, and told me that it was noon. The church stands among its graves, a little removed from the wayside, quite apart from any collection of houses, and with no signs of a vicarage; it is a good deal shadowed by trees, and not wholly destitute of ivy. The body of the edifice, unfortunately, (and it is an outrage which the English churchwardens are fond of perpetrating,) has been newly covered with a yellowish plaster or wash, so as quite to destroy the aspect of antiquity, except upon the tower, which wears the dark gray hue of many centuries. The chancel-window is painted with a representation of Christ upon the Cross, and all the other windows are full of painted or stained glass, but none of it ancient, nor (if it be fair to judge from without of what ought to be seen within) possessing any of the tender glory that should be the inheritance of this branch of Art, revived from mediaeval times. I stepped over the graves, and peeped in at two or three of the windows, and saw the snug interior of the church glimmering through the many-colored panes, like a show of commonplace objects under the fantastic influence of a dream: for the floor was covered with modern pews, very like what we may see in a New-England meeting-house, though, I think, a little more favorable than those would be to the quiet slumbers of the Hatton farmers and their families. Those who slept under Doctor Parr's preaching now prolong their nap, I suppose, in the church-yard round about, and can scarcely have drawn much spiritual benefit from any truths that he contrived to tell them in their lifetime. It struck me as a rare example (even where examples are numerous) of a man utterly misplaced, that this enormous scholar, great in the classic tongues, and inevitably converting his own simplest vernacular into a learned language, should have been set up in this homely pulpit, and ordained to preach salvation to a rustic audience, to whom it is difficult to imagine how he could ever have spoken one available word.

Almost always, in visiting such scenes as I have been attempting to describe, I had a singular sense of having been there before. The ivy-grown English churches (even that of Bebbington, the first that I beheld) were quite as familiar to me, when fresh from home, as the old wooden meeting-house in Salem, which used, on wintry Sabbaths, to be the frozen purgatory of my childhood. This was a bewildering, yet very delightful emotion, fluttering about me like a faint summer-wind, and filling my imagination with a thousand half-remembrances, which looked as vivid as sunshine, at a side-glance, but faded quite away whenever I attempted to grasp and define them. Of course, the explanation of the mystery was, that history, poetry, and fiction, books of travel, and the talk of tourists, had given me pretty accurate preconceptions of the common objects of English scenery, and these, being long ago vivified by a youthful fancy, had insensibly taken their places among the images of things actually seen. Yet the illusion was often so powerful, that I almost doubted whether such airy remembrances might not be a sort of innate idea, the print of a recollection in some ancestral mind, transmitted, with fainter and fainter impress through several descents, to my own. I felt, indeed, like the stalwart progenitor in person, returning to the hereditary haunts after more than two hundred years, and finding the church, the hall, the farm-house, the cottage, hardly changed during his long absence,—the same shady by-paths and hedge-lanes, the same veiled sky, and green lustre of the lawns and fields,—while his own affinities for these things, a little obscured by disuse, were reviving at every step.

An American is not very apt to love the English people, as a whole, on whatever length of acquaintance. I fancy that they would value our regard, and even reciprocate it in their ungracious way, if we could give it to them in spite of all rebuffs; but they are beset by a curious and inevitable infelicity, which compels them, as it were, to keep up what they seem to consider a wholesome bitterness of feeling between themselves and all other nationalities, especially that of America. They will never confess it; nevertheless, it is as essential a tonic to them as their bitter ale. Therefore—and possibly, too, from a similar narrowness in his own character—an American seldom feels quite as if he were at home among the English people. If he do so, he has ceased to be an American. But it requires no long residence to make him love their island, and appreciate it as thoroughly as they themselves do. For my part, I used to wish that we could annex it, transferring their thirty millions of inhabitants to some convenient wilderness in the great West, and putting half or a quarter as many of ourselves into their places. The change would be beneficial to both parties. We, in our dry atmosphere, are getting too nervous, haggard, dyspeptic, extenuated, unsubstantial, theoretic, and need to be made grosser. John Bull, on the other hand, has grown bulbous, long-bodied, short-legged, heavy-witted, material, and, in a word, too intensely English. In a few more centuries he will be the earthliest creature that ever the earth saw. Heretofore Providence has obviated such a result by timely intermixtures of alien races with the old English stock; so that each successive conquest of England has proved a victory, by the revivification and improvement of its native manhood. Cannot America and England hit upon some scheme to secure even greater advantages to both nations?

SANITARY CONDITION OF THE ARMY

The power and efficiency of an army consist in the amount of the power and efficiency of its elements, in the health, strength, and energy of its members. No army can be strong, however numerous its soldiers, if they are weak; nor is it completely strong, unless every member is in full vigor. The weakness of any part, however small, diminishes, to that extent, the force of the whole; and the increase of power in any part adds so much to the total strength.

In order, then, to have a strong and effective army, it is necessary not only to have a sufficient number of men, but that each one of these should have in himself the greatest amount of force, the fullest health and energy the human body can present.

This is usually regarded in the original creation of an army. The soldiers are picked men. None but those of perfect form, complete in all their organization and functions, and free from every defect or disease, are intended to be admitted. The general community, in civil life, includes not only the strong and healthy, but also the defective, the weak, and the sick, the blind, the halt, the consumptive, the rheumatic, the immature in childhood, and the exhausted and decrepit in age.

In the enlistment of recruits, the candidates for the army are rigidly examined, and none are admitted except such as appear to be mentally and physically sound and perfect. Hence, many who offer their services to the Government are rejected, and sometimes the proportion accepted is very small.

In Great Britain and Ireland, during the twenty years from 1832 to 1851 inclusive, 305,897 applied for admission into the British army. Of these, 97,457, or 32 per cent., were rejected, and only 208,440, or 68 per cent., were accepted.2

In France, during thirteen years, 1831 to 1843 inclusive, 2,280,540 were offered for examination as candidates for the army. Of these, 182,664, being too short, though perhaps otherwise in possession of all the requisites of health, were not examined, leaving 2,097,876, who were considered as candidates for examination. Of these, 680,560, or 32.5 per cent, were rejected on account of physical unfitness, and only 1,417,316, or 67.5 per cent., were allowed to join the army.3

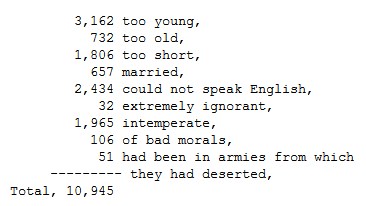

The men who ordinarily offer for the American army, in time of peace, are of still inferior grade, as to health and strength. In the year 1852, at the several recruiting-stations, 16,114 presented themselves for enlistment, and 10,945, or 67.9 per cent., were rejected, for reasons not connected with health:—

All of these may have been in good health.

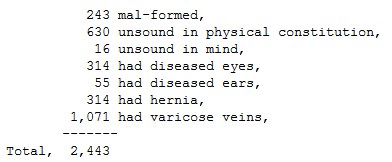

Of the remainder, 5,169, who were subjects of further inquiry, 2,443 were rejected for reasons connected with their physical or mental condition:—

Only 2,726 were accepted, being 52.7 per cent, of those who were examined, and less than 17 per cent., or about one-sixth, of all who offered themselves as candidates for the army, in that year.4

In time of peace, the character of the men who desire to become soldiers differs with the degree of public prosperity. When business is good, most men obtain employment in the more desirable and profitable avocations of civil life. Then a larger proportion of those who are willing to enter the army are unfitted, by their habits or their health, for the occupations of peace, and go to the rendezvous only as a last resort, to obtain their bread. But when business falters, a larger and a better class are thrown out of work, and are glad to enter the service of the country by bearing arms. The year 1852 was one of prosperity, and affords, therefore, no indication of the class and character of men who are willing to enlist in the average years. The Government Reports state that in some other years 6,383 were accepted and 3,617 rejected out of 10,000 that offered to enlist. But in time of war, when the country is endangered, and men have a higher motive for entering its service than mere employment and wages, those of a better class both as to character and health flock to the army; and in the present war, the army is composed, in great degree, of men of the highest personal character and social position, who leave the most desirable and lucrative employments to serve their country as soldiers.

As, then, the army excludes, or intends to exclude, from its ranks all the defective, weak, and sick, it begins with a much higher average of health and vigor, a greater power of action, of endurance, and of resisting the causes of disease, than the mass of men of the same ages in civil life. It is composed of men in the fulness of strength and efficiency. This is the vital machinery with which Governments propose to do their martial work; and the amount of vital force which belongs to these living machines, severally and collectively, is the capital with which they intend to accomplish their purposes. Every wise Government begins the business of war with a good capital of life, a large quantity of vital force in its army. So far they do well; but more is necessary. This complete and fitting preparation alone is not sufficient to carry on the martial process through weeks and months of labor and privation. Not only must the living machinery of bone and flesh be well selected, but its force must be sustained, it must be kept in the most effective condition and in the best and most available working order. For this there are two established conditions, that admit of no variation nor neglect: first, a sufficient supply of suitable nutriment, and faithful regard to all the laws of health; and, second, the due appropriation of the vital force that is thus from day to day created.

A due supply of appropriate food and of pure air, sufficient protection and cleansing of the surface, moderate labor and refreshing rest, are the necessary conditions of health, and cannot be disregarded, in the least degree, without a loss of force. The privation of even a single meal, or the use of food that is hard of digestion or innutritious, and the loss of any of the needful sleep, are followed by a corresponding loss of effective power, as surely as the slackened fire in the furnace is followed by lessened steam and power in the engine.

Whosoever, then, wishes to sustain his own forces or those of his laborers with the least cost, and use them with the greatest effect, must take Nature on her own terms. It is vain to try to evade or alter her conditions. The Kingdom of Heaven is not divided against itself. It makes no compromises, not even for the necessities of nations. It will not consent that any one, even the least, of its laws shall be set aside, to advance any other, however important. Each single law stands by itself, and exacts complete obedience to its own requirements: it gives its own rewards and inflicts its own punishments. The stomach will not digest tough and hard or old salted meats, or heavy bread, without demanding and receiving a great and perhaps an almost exhausting proportion of the nervous energies. The nutritive organs will not create vigorous muscles and effective limbs, unless the blood is constantly and appropriately recruited. The lungs will not decarbonize and purify the blood with foul air, that has been breathed over and over and lost its oxygen. However noble or holy the purpose for which human power is to be used, it will not be created, except according to the established conditions. The strength of the warrior in battle cannot be sustained, except in the appointed way, even though the fate of all humanity depend on his exertions.

Nature keeps an exact account with all her children, and gives power in proportion to their fulfilment of her conditions. She measures out and sustains vital force according to the kind and fitness of the raw material provided for her. When we deal liberally with her, she deals liberally with us. For everything we give to her she makes a just return. The stomach, the nutrient arteries, the lungs, have no love, no patriotism, no pity; but they are perfectly honest. The healthy digestive organs will extract and pay over to the blood-vessels just so much of the nutritive elements as the food we eat contains in an extractible form, and no more; and for this purpose they will demand and take just so much of the nervous energy as may be needed. The nutrient arteries will convert into living flesh just so much of the nutritive elements as the digestive organs give them, and no more. The lungs will send out from the body as many of the atoms of exhausted and dead flesh as the oxygen we give them will convert into carbonic acid and water, and this is all they can do. In these matters, the vital organs are as honest and as faithful as the boiler, that gives forth steam in the exact ratio of the heat which the burning fuel evolves and the fitness of the water that is supplied to it; and neither can be persuaded to do otherwise. The living machine of bone and flesh and the dead machine of iron prepare their forces according to the means they have, not according to the ulterior purpose to which those forces are to be applied. They do this alike for all. They do it as well for the sinner as for the saint,—as well for the traitorous Secessionist striving to destroy his country as for the patriot endeavoring to sustain it.