полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 10, No. 60, October, 1862

In neither case is it a matter of will, but of necessity. The amount of power to be generated in both living and dead machines is simply a question of quality and quantity of provision for the purpose. So much food, air, protection given produce so much strength. A proposition to reduce the amount of either of these necessarily involves the proposition to reduce the available force. Whoever determines to eat or give his men less or poorer food, or impure air, practically determines to do less work. In all this management of the human body, we are sure to get what we pay for, and we are equally sure not to get what we do not pay for.

All Governments have tried, and are now, in various degrees, trying, the experiment of privation in their armies. The soldier cannot carry with him the usual means and comforts of home. He must give these up the moment he enters the martial ranks, and reduce his apparatus of living to the smallest possible quantity. He must generally limit himself to a portable house, kitchen, cooking-apparatus, and wardrobe, and to an entire privation of furniture, and sometimes submit to a complete destitution of everything except the provision he may carry in his haversack and the blanket he can carry on his back. When stationary, he commonly sleeps in barracks; but he spends most of his time in the field and sleeps in tents. Occasionally he is compelled to sleep in the open air, without any covering but his blanket, and to cook in an extemporized kitchen, which he may make of a few stones piled together or of a hole in the earth, with only a kettle, that he carries on his back, for cooking-apparatus. In all cases and conditions, whether in fort or in field, in barrack, tent, or open air, he is limited to the smallest artificial habitation, the least amount of furniture and conveniences, the cheapest and most compact food, and the rudest cookery. He is, therefore, never so well protected against the elements, nor, when sleeping under cover, so well supplied with air for respiration, as he is at home. Moreover, when lodging abroad, he cannot take his choice of places; he is liable, from the necessities of war, to encamp in wet and malarious spots, and to be exposed to chills and miasms of unhealthy districts. He is necessarily exposed to weather of every kind,—to cold, to rains, to storms; and when wet, he has not the means of warming himself, nor of drying or changing his clothing. His life, though under martial discipline, is irregular. At times, he has to undergo severe and protracted labors, forced marches, and the violent and long-continued struggles of combat; at other times, he has not exercise sufficient for health. His food is irregularly served. He is sometimes short of provisions, and compelled to pass whole days in abstinence or on shore allowance. Occasionally he cannot obtain even water to drink, through hours of thirsty toil. No Government nor managers of war have ever yet been able to make exact and unfailing provision for the wants and necessities of their armies, as men usually do for themselves and their families at home.

SUPPOSED DANGERS TO THE SOLDIER

From the earliest recorded periods of the world, men have gone forth to war, for the purpose of destroying or overcoming their enemies, and with the chance of being themselves destroyed or overthrown. Public authorities have generally taken account of the number of their own men who have been wounded and killed in battle, and of the casualties in the opposing armies. Gunpowder and steel, and the manifold weapons, instruments, and means of destruction in the hands of the enemy are commonly considered as the principal, if not the only sources of danger to the soldier, and ground of anxiety to his friends; and the nation reckons its losses in war by the number of those who were wounded and killed in battle. But the suffering and waste of life, apart from the combat, the sickness, the depreciation of vital force, the withering of constitutional energy, and the mortality in camp and fortress, in barrack, tent, and hospital, have not usually been the subjects of such careful observation, nor the grounds of fear to the soldier and of anxiety to those who are interested in his safety. Consequently, until within the present century, comparatively little attention has been given to the dangers that hang over the army out of the battle-field, and but little provision has been made, by the combatants or their rulers, to obviate or relieve them. No Government in former times, and few in later years, have taken and published complete accounts of the diseases of their armies, and of the deaths that followed in consequence. Some such records have been made and printed, but these are mostly fragmentary and partial, and on the authority of individuals, officers, surgeons, scholars, and philanthropists.

It must not be forgotten that the army is originally composed of picked men, while the general community includes not only the imperfect, diseased, and weak that belong to itself, but also those who are rejected from the army. If, then, the conditions, circumstances, and habits of both were equally favorable, there would be less sickness and a lower rate of mortality among the soldiers than among men of the same ages at home. But if in the army there should be found more sickness and death than in the community at home, or even an equal amount, it is manifestly chargeable to the presence of more deteriorating and destructive influences in the military than in civil life.

SICKNESS AND MORTALITY IN CIVIL LIFE

The amount of sickness among the people at home is not generally recognized, still less is it carefully measured and recorded. But the experience and calculations of the Friendly Societies of Great Britain, and of other associations for Health-Assurance there and elsewhere, afford sufficient data for determining the proportion of time lost in sickness by men of various ages. These Friendly Societies are composed mainly of men of the working-classes, from which most of the soldiers of the British army are drawn.

According to the calculations and tables of Mr. Ansel, in his work on "Friendly Societies," the men of the army-ages, from 20 to 40, in the working-classes, lose, on an average, five days and six-tenths of a day by sickness in each year, which will make one and a half per cent, of the males of this age and class constantly sick. Mr. Neison's calculations and tables, in his "Contributions to Vital Statistics," make this average somewhat over seven days' yearly sickness, and one and ninety-two hundredths of one per cent, constantly sick. These were the bases of the rates adopted by the Health-Assurance companies in New England, and their experience shows that the amount of sickness in these Northern States is about the same as, if not somewhat greater than, that in Great Britain, among any definite number of men.

The rate of mortality is more easily ascertained, and is generally calculated and determined in civilized nations. This rate, among all classes of males, between 20 and 40 years old, in England and Wales, is .92 per cent.: that is, 92 will die out of 10,000 men of these ages, on an average, in each year; but in the healthiest districts the rate is only 77 in 10,000. The mortality among the males of Massachusetts, of the same ages, according to Mr. Elliott's calculations, is 1.11 per cent, or 111 in 10,000. This maybe safely assumed as the rate of mortality in all New England. That of the Southern States is somewhat greater.

These rates of sickness and death—one and a half or one and ninety-two hundredths per cent, constantly sick, and seventy-seven to one hundred and eleven dying, in each year, among ten thousand living—may be considered as the proportion of males, of the army-ages, that should be constantly taken away from active labor and business by illness, and that should be annually lost by death. Whether at home, amidst the usually favorable circumstances and the average comforts, or in the army, under privation and exposure, men of these ages may be presumed to be necessarily subject to this amount, at least, of loss of vital force and life. And these rates may be adopted as the standard of comparison of the sanitary influences of civil and military life.

SICKNESS AND MORTALITY OF THE ARMY IN PEACE

Soldiers are subject to different influences and exposures, and their waste and loss of life differ, in peace and war. In peace they are mostly stationary, at posts, forts, and in cantonments. They generally live in barracks, with fixed habits and sufficient means of subsistence. They have their regular supplies of food and clothing and labor, and are protected from the elements, heat, cold, and storms. They are seldom or never subjected to privation or excessive fatigue. But in war they are in the field, and sleep in tents which are generally too full and often densely crowded. Sometimes they sleep in huts, and occasionally in the open air. They are liable to exposures, hardships, and privations, to uncertain supplies of food and bad cookery.

The report of the commission appointed by the British Government to inquire into the sanitary condition, of the army shows a remarkable and unexpected degree of mortality among the troops stationed at home under the most favorable circumstances, as well as among those abroad. The Foot-Guards are the very élite of the whole army; they are the most perfect of the faultless in form and in health. They are the pets of the Government and the people. They are stationed at London and Windsor, and lodged in magnificent barracks, apparently ample for their accommodation. They are clothed and fed with extraordinary care, and are supposed to have every means of health. And yet their record shows a sad difference between their rate of mortality and that of men of the same ages in civil life. A similar excess of mortality was found to exist among all the home-army, which includes many thousand soldiers, stationed in various towns and places throughout the kingdom.

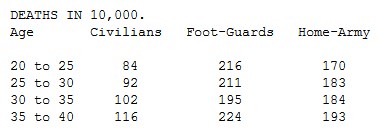

The following table exhibits the annual mortality in these classes.5

Through the fifteen years from 1839 to 1853 inclusive, the annual mortality of all the army, excepting the artillery, engineers, and West India and colonial corps, was 330 among 10,000 living; while that among the same number of males of the army-ages, in all England and Wales, was 92, and in the healthiest districts only 77.6

There is no official account at hand of the general mortality in the Russian army on the peace-establishment; yet, according to Boudin, in one portion, consisting of 192,834 men, 144,352 had been sick, and 7,541, or 38 per 1,000, died in one year.7

The Prussian army, with an average of 150,582 men, lost by death, during the ten years 1829 to 1838, 1,975 in each year, which is at the rate of 13 per 1,000 living.8

The mortality of the Piedmontese army, from 1834 to 1843 inclusive, was 158 in 10,000, while that of the males at home was 92 in the same number living.

From 1775 to 1791, seventeen years, the mortality among the cavalry was 181, and among the infantry 349, out of 10,000 living; but in the ten years from 1834 to 1843 these rates were only 108 and 215.9

Colored troops are employed by the British Government in all their colonies and possessions in tropical climates. The mortality of these soldiers is known, and also that of the colored male civilians in the East Indies and in the West-India Islands and South-American Provinces. In four of these, the rate of mortality is higher among the male slaves than among the colored soldiers; but in all the others, this rate is higher in the army. In all the West-Indian and South-American possessions of Great Britain, the average rate of deaths is 25 per cent, greater among the black troops than among the black males of all ages on the plantations and in the towns. The soldiers are of the healthier ages, 20 to 40, but the civilians include both the young and the old: if these could be excluded, and the comparison made between soldiers and laborers of the same ages, the difference in favor of civil pursuits would appear much greater.

Throughout the world, where the armies of Great Britain are stationed or serve, the death-rate is greater among the troops than among civilians of the same races and ages, except among the colored troops in Tobago, Montserrat, Antigua, and Granada in America, and among the Sepoys in the East Indies.10

In the army of the United States, during the period from 1840 to 1854, not including the two years of the Mexican War, there was an average of 9,278 men, or an aggregate of 120,622 years of service, equal to so many men serving one year. Among these and during this period, there were 342,107 cases of sickness reported by the surgeons, and 3,416 deaths from disease, showing a rate of mortality of 2.83 per cent., or two and a half times as great as that among the males of Massachusetts of the army-ages, and three times as great as that in England and Wales. The attacks of sickness average almost three for each man in each year. This is manifestly more than that which falls upon men of these ages at home.11

SICKNESS AND MORTALITY OF THE ARMY IN WAR

Thus far the sickness and mortality of the army in time of peace only has been considered. The experience of war tells a more painful story of the dangers of the men engaged in it. Sir John Pringle states, that, in the British armies that were sent to the Low Countries and Germany, in the years 1743 to 1747, a great amount of sickness and mortality prevailed. He says, that, besides those who were suffering from wounds, "at some periods more than one-fifth of the army were in the hospitals." "One regiment had over one-half of its men sick." "In July and August, 1743, one-half of the army had the dysentery." "In 1747, four battalions," of 715 men each, "at South Beveland and Walcheren, both in field and in quarters, were so very sickly, that, at the height of the epidemic, some of these corps had but one hundred men fit for duty; six-sevenths of their numbers were sick."12 "At the end of the campaign the Royal Battalion had but four men who had not been ill." And "when these corps went into winter-quarters, their sick, in proportion to their men fit for duty, were nearly as four to one."13 In 1748, dysentery prevailed. "In one regiment of 500 men, 150 were sick at the end of five weeks; 200 were sick after two months; and at the end of the campaign, they had in all but thirty who had never been ill." "In Johnson's regiment sometimes one-half were sick; and in the Scotch Fusileers 300 were ill at one time."14

The British army in Egypt, in 1801, had from 103 to 261 and an average of 182 sick in each thousand; and the French army had an average of 125 in 1,000, or one-eighth of the whole, on the sick-list.15

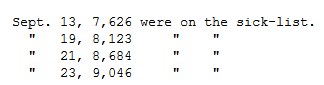

In July, 1809, the British Government sent another army, of 39,219 men, to the Netherlands. They were stationed at Walcheren, which was the principal seat of the sickness and suffering of their predecessors, sixty or seventy years before. Fever and dysentery attacked this second army as they had the first, and with a similar virulence and destructiveness. In two months after landing,

In ninety-seven days 12,867 were sent home sick; and on the 22d of October there were only 4,000 effective men left fit for duty out of this army of about 40,000 healthy men, who had left England within less than four months. On the 1st of February of the next year, there were 11,513 on the sick-list, and 15,570 had been lost or disabled. Between January 1st and June of the same year, (1810,) 36,500 were admitted to the hospitals, and 8,000, or more than 20 per cent., died, which is equal to an annual rate of 48 per cent, mortality.

The British army in Spain and Portugal suffered greatly through the Peninsular War, from 1808 to 1814. During the whole of that period, there was a constant average of 209 per 1,000 on the sick-list, and the proportion was sometimes swelled to 330 per 1,000. Through the forty-one months ending May 25th, 1814, with an average of 61,511 men, there was an average of 13,815 in the hospitals, which is 22.5 per cent.; of these only one-fifteenth, or 1.5 per cent. of the whole army, were laid up on account of injuries in battle, and 21 per cent. were disabled by diseases. From these causes 24,930 died, which is an annual average of 7,296, or a rate of 11.8 per cent, mortality.16

No better authority can be adduced, for the condition of men engaged in the actual service of war, than Lord Wellington. On the 14th of November, 1809, he wrote from his army in Spain to Lord Liverpool, then at the head of the British Government,—"In all times and places the sick-list of the army amounts to ten per cent of all."17 He seemed to consider this the lowest attainable rate of sickness, and he hoped to be able to reduce that of his own army to it: this is more than five times as great as the rate of sickness among male civilians of the army-ages. The sickness in Lord Wellington's army, at the moment of writing this despatch, was fifteen per cent., or seven and a half times as great as that at home.

In the same Peninsular War, there was of the sick in the French army a constant average of 136 per 1,000 in Spain, and 146 per 1,000 in Portugal. Mr. Edmonds says, that, just before the Battle of Talavera, the French army consisted of 275,000 men, of whom 61,000, or 22.2 per cent., were sick.18 Lord Wellington wrote, Sept. 19, 1809, that the French army of 225,000 men had 30,000 to 40,000 sick, which is 13.3 to 17.7 per cent. The French army in Portugal had at one time 64 per 1,000, and at another 235 per 1,000, and an average of 146 per 1,000, in the hospitals through the war.

The British army that fought the Battle of Waterloo, in 1815, had an average of 60,992 men, through the campaign of four months, June to September; of these, there was an average of 7,909, or 12.9 per cent., in the hospitals.19

The British legion that went to Spain in 1836 consisted of 7,000 men. Of these, 5,000, or 71 per cent., were admitted into the hospitals in three and a half months, and 1,223 died in six months. This is equal to an annual rate of almost two and a half, 2.44, attacks for each man, and of 34.9 per cent. mortality.20

"Of 115,000 Russians who invaded Turkey in 1828 and 1829, only 10,000 or 15,000 ever repassed the Pruth. The rest died there of intermittent fevers, dysenteries, and plague." "From May, 1828, to February, 1829, 210,108 patients were admitted into the general and regimental hospitals." "In October, 1828, 20,000 entered the general hospitals." "The sickness was very fatal." "More than a quarter of the fever-patients died." "5,509 entered the hospitals, and of these, 3,959 died in August, 1829, and only 614 ultimately recovered." "At Brailow the plague attacked 1,200 and destroyed 774." "Dysentery was equally fatal." "In the march across the Balkan, 1,000 men died of diarrhoea, fever, and scurvy." "In Bulgaria, during July, 37,000 men were taken sick." "At Adrianople a vast barrack was taken for a hospital, and in three days 1,616 patients were admitted. On the first of September there were 3,666, and on the 15th, 4,646 patients in the house. This was one-quarter of all the disposable force at that station." "In October, 1,300 died of dysentery; and at the end of the month there were 4,700 in the hospitals." "In the whole army the loss to the Russians in the year 1829 was at least 60,000 men."21

CRIMEAN WAR

In 1854, twenty-five years after this fatal experience of the Russian army in Bulgaria, the British Government sent an army to the same province, where the men were exposed to the same diseases and suffered a similar depreciation of vital force in sickness and death. For two years and more they struggled with these destructive influences in their own camps, in Bulgaria and the Crimea, with the usual result of such exposures in waste of life. From April 10, 1854, to June 30, 1856, 82,901 British soldiers were sent to the Black Sea and its coasts; and through these twenty-six and two-thirds months the British army had an average of 34,559 men engaged in that "War in the East" with Russia. From these there were furnished to the general and regimental, the stationary and movable hospitals 218,952 cases: 24,084, or 11 per cent, of these patients were wounded or injured in battle, and 194,868, or 89 per cent, suffered from the diseases of the camp. This is equal to an annual average of two and a half attacks of sickness for each man. The published reports give an analysis of only 162,123 of these cases of disease. Of these, 110,673, or 68 per cent., were of the zymotic class,—fevers, dysenteries, scurvy, etc., which are generally supposed to be due to exposure and privation, and other causes which are subject to human control. During the two years ending with March, 1856, 16,224 died of diseases, of which 14,476 were of the zymotic or preventable class, 2,755 were killed in battle, and 2,019 died of wounds and injuries received in battle. The annual rate of mortality, from all diseases, was 23 per cent; from zymotic diseases, 21 per cent.; from battle, 6.9 per cent. The rate of sickness and mortality varied exceedingly in different months. In April, May, and June, 1854, the deaths were at the annual rate of 8.7 per 1,000; in July, 159 per 1,000; in August and September, 310 per 1,000; in December, this rate again rose and reached 679 per 1,000; and in January, 1855, owing to the great exposures, hardships, and privations in the siege, and the very imperfect means of sustenance and protection, the mortality increased to the enormous rate of 1,142 per 1,000, so that, if it had continued unabated, it would have destroyed the whole army in ten and a half months.22

AMERICAN ARMY, 1812 TO 1814

We need not go abroad to find proofs of the waste of life in military camps. Our own army, in the war with Great Britain in 1812–14, suffered, as the European armies have done, by sickness and death, far beyond men in civil occupations. There are no comprehensive reports, published by the Government, of the sanitary condition and history of the army on the Northern frontier during that war. But the partial and fragmentary statements of Dr. Mann, in his "Medical Sketches," and the occasional and apparently incidental allusions to the diseases and deaths by the commanding officers, in their letters and despatches to the Secretary of War, show that sickness was sometimes fearfully prevalent and fatal among our soldiers. Dr. Mann says: "One regiment on the frontier, at one time, counted 900 strong, but was reduced, by a total want of a good police, to less than 200 fit for duty." "At one period more than 340 were in the hospitals, and, in addition to this, a large number were reported sick in camp."23 "The aggregate of the army at Fort George and its dependencies was about 5,000. From an estimate of the number sick in the general and regimental hospitals, it was my persuasion that but little more than half of the army was capable of duty, at one period, during the summer months"24 of 1813. "During the month of August more than one-third of the soldiers were on the sick-reports."25 Dr. Mann quotes Dr. Lovell, another army-surgeon, who says, in the autumn of 1813: "A morning report, now before me, gives 75 sick, out of a corps of 160. The several regiments of the army, in their reports, exhibit a proportional number unfit for duty."26 Dr. Mann states that "the troops at Burlington, Vt., in the winter of 1812–13, did not number over 1,600, and the deaths did not exceed 200, from the last of November to the last of February."27 But Dr. Gallup says: "The whole number of deaths is said to be not less than 700 to 800 in four months," and "the number of soldiers stationed at this encampment [Burlington] was about 2,500 to 2,800."28 According to Dr. Mann's statement, the mortality was at the annual rate of 50 per cent.; and according to that of Dr. Gallup, it was at the rate of 75 to 96 per cent. This is nearly equal to the severest mortality in the Crimea.

General William H. Harrison, writing to the Secretary of War from the borders of Lake Erie, Aug. 29, 1813, says: "You can form some estimate of the deadly effects of the immense body of stagnant water with which the vicinity of the lake abounds, from the state of the troops at Sandusky. Upwards of 90 are this morning reported sick, out of about 220." This is a rate of over 40 per cent. "Those at Fort Meigs are not much better."29