полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

8. The birth and history of Lingo

The yellow flowers of the tree Pahindi were growing on Dhawalgiri. Bhagwān sent thunder and lightning, and the flower conceived. First fell from it a heap of turmeric or saffron. In the morning the sun came out, the flower burst open, and Lingo was born. Lingo was a perfect child. He had a diamond on his navel and a sandalwood mark on his forehead. He fell from the flower into the heap of turmeric. He played in the turmeric and slept in a swing. He became nine years old. He said there was no one there like him, and he would go where he could find his fellows. He climbed a needle-like hill,49 and from afar off he saw Kachikopa Lohāgarh and the four Gonds. He came to them. They saw he was like them, and asked him to be their brother. They ate only animals. Lingo asked them to find for him an animal without a liver, and they searched all through the forest and could not. Then Lingo told them to cut down trees and make a field. They tried to cut down the anjan50 trees, but their hands were blistered and they could not go on. Lingo had been asleep. He woke up and saw they had only cut down one or two trees. He took the axe and cut down many trees, and fenced a field and made a gate to it. Black soil appeared. It began to rain, and rained without ceasing for three days. All the rivers and streams were filled. The field became green with rice, and it grew up. There were sixteen score of nīlgai or blue-bull. They had two leaders, an old bull and his nephew. The young bull saw the rice of Lingo’s field and wished to eat it. The uncle told him not to eat of the field of Lingo or all the nīlgai would be killed. But the young bull did not heed, and took off all the nīlgai to eat the rice. When they got to the field they could find no entrance, so they jumped the fence, which was five cubits high. They ate all the rice from off the field and ran away. The young bull told them as they ran to put their feet on leaves and stones and boughs and grass, and not on the ground, so that they might not be tracked. Lingo woke up and went to see his field, and found all the rice eaten. He knew the nīlgai had done it, and showed the brothers how to track them by the few marks which they had by accident made on the ground. They did so, and surrounded the nīlgai and killed them all with their bows and arrows except the old uncle, from whom Lingo’s arrow rebounded harmlessly on account of his innocence, and one young doe. From these two the nīlgai race was preserved. Then Lingo told the Gonds to make fire and roast the deer as follows:

He said, I will show you something; see if anywhere in your

Waistbands there is a flint; if so, take it out and make fire.

But the matches did not ignite. As they were doing this, a watch of the night passed.

They threw down the matches, and said to Lingo, Thou art a Saint;

Show us where our fire is, and why it does not come out.

Lingo said: Three koss (six miles) hence is Rikad Gawādi the giant.

There is fire in his field; where smoke shall appear, go there,

Come not back without bringing fire. Thus said Lingo.

They said, We have never seen the place, where shall we go?

Ye have never seen where this fire is? Lingo said;

I will discharge an arrow thither.

Go in the direction of the arrow; there you will get fire.

He applied the arrow, and having pulled the bow, he discharged one:

It crashed on, breaking twigs and making its passage clear.

Having cut through the high grass, it made its way and reached the old man’s place (above mentioned).

The arrow dropped close to the fire of the old man, who had daughters.

The arrow was near the door. As soon as they saw it, the daughters came and took it up,

And kept it. They asked their father: When will you give us in marriage?

Thus said the seven sisters, the daughters of the old man.

I will marry you as I think best for you;

Remain as you are. So said the old man, the Rikad Gawādi.

Lingo said, Hear, O brethren! I shot an arrow, it made its way.

Go there, and you will see fire; bring thence the fire.

Each said to the other, I will not go; but (at last) the youngest went.

He descried the fire, and went to it; then beheld he an old man looking like the trunk of a tree.

He saw from afar the old man’s field, around which a hedge was made.

The old man kept only one way to it, and fastened a screen to the entrance, and had a fire in the centre of the field.

He placed logs of the Mahua and Anjun and Sāj trees on the fire,

Teak faggots he gathered, and enkindled flame.

The fire blazed up, and warmed by the heat of it, in deep sleep lay the Rikad Gawādi.

Thus the old man like a giant did appear. When the young Gond beheld him, he shivered;

His heart leaped; and he was much afraid in his mind, and said:

If the old man were to rise he will see me, and I shall be eaten up;

I will steal away the fire and carry it off, then my life will be safe.

He went near the fire secretly, and took a brand of tendu wood tree.

When he was lifting it up a spark flew and fell on the hip of the old man.

That spark was as large as a pot; the giant was blistered; he awoke alarmed.

And said: I am hungry, and I cannot get food to eat anywhere; I feel a desire for flesh;

Like a tender cucumber hast thou come to me. So said the old man to the Gond,

Who began to fly. The old man followed him. The Gond then threw away the brand which he had stolen.

He ran onward, and was not caught. Then the old man, being tired, turned back.

Thence he returned to his field, and came near the fire and sat, and said, What nonsense is this?

A tender prey had come within my reach;

I said I will cut it up as soon as I can, but it escaped from my hand!

Let it go; it will come again, then I will catch it. It has gone now.

Then what happened? the Gond returned and came to his brethren.

And said to them: Hear, O brethren, I went for fire, as you sent me, to that field; I beheld an old man like a giant.

With hands stretched out and feet lifted up. I ran. I thus survived with difficulty.

The brethren said to Lingo, We will not go. Lingo said, Sit ye here.

O brethren, what sort of a person is this giant? I will go and see him.

So saying, Lingo went away and reached a river.

He thence arose and went onward. As he looked, he saw in front three gourds.

Then he saw a bamboo stick, which he took up.

When the river was flooded

It washed away a gourd tree, and its seed fell, and each stem produced bottle-gourds.

He inserted a bamboo stick in the hollow of the gourd and made a guitar.

He plucked two hairs from his head and strung it.

He held a bow and fixed eleven keys to that one stick, and played on it.

Lingo was much pleased in his mind.

Holding it in his hand, he walked in the direction of the old man’s field.

He approached the fire where Rikad Gawādi was sleeping.

The giant seemed like a log lying close to the fire; his teeth were hideously visible;

His mouth was gaping. Lingo looked at the old man while sleeping.

His eyes were shut. Lingo said, This is not a good time to carry off the old man while he is asleep.

In front he looked, and turned round and saw a tree

Of the pīpal sort standing erect; he beheld its branches with wonder, and looked for a fit place to mount upon.

It appeared a very good tree; so he climbed it, and ascended to the top of it to sit.

As he sat the cock crew. Lingo said, It is daybreak;

Meanwhile the old man must be rising. Therefore Lingo took the guitar in his hand,

And held it; he gave a stroke, and it sounded well; from it he drew one hundred tunes.

It sounded well, as if he was singing with his voice.

Thus (as it were) a song was heard.

Trees and hills were silent at its sound. The music loudly entered into

The old man’s ears; he rose in haste, and sat up quickly; lifted up his eyes,

And desired to hear (more). He looked hither and thither, but could not make out whence the sound came.

The old man said: Whence has a creature come here to-day to sing like the maina bird?

He saw a tree, but nothing appeared to him as he looked underneath it.

He did not look up; he looked at the thickets and ravines, but

Saw nothing. He came to the road, and near to the fire in the midst of his field and stood.

Sometimes sitting, and sometimes standing, jumping, and rolling, he began to dance.

The music sounded as the day dawned. His old woman came out in the morning and began to look out.

She heard in the direction of the field a melodious music playing.

When she arrived near the edge of her field, she heard music in her ears.

That old woman called her husband to her.

With stretched hands, and lifted feet, and with his neck bent down, he danced.

Thus he danced. The old woman looked towards her husband, and said, My old man, my husband,

Surely, that music is very melodious. I will dance, said the old woman.

Having made the fold of her dress loose, she quickly began to dance near the hedge.

9. Death and resurrection of Lingo

Then Lingo disclosed himself to the giant and became friendly with him. The giant apologised for having tried to eat his brother, and called Lingo his nephew. Lingo invited him to come and feast on the flesh of the sixteen scores of nīlgai. The giant called his seven daughters and offered them all to Lingo in marriage. The daughters produced the arrow which they had treasured up as portending a husband. Lingo said he was not marrying himself, but he would take them home as wives for his brothers. So they all went back to the cave and Lingo assigned two of the daughters each to the three elder brothers and one to the youngest. Then the brothers, to show their gratitude, said that they would go and hunt in the forest and bring meat and fruit and Lingo should lie in a swing and be rocked by their seven wives. But while the wives were swinging Lingo and his eyes were shut, they wished to sport with him as their husbands’ younger brother. So saying they pulled his hands and feet till he woke up. Then he reproached them and called them his mothers and sisters, but they cared nothing and began to embrace him. Then Lingo was filled with wrath and leapt up, and seeing a rice-pestle near he seized it and beat them all with it soundly. Then the women went to their houses and wept and resolved to be revenged on Lingo. So when the brothers came home they told their husbands that while they were swinging Lingo he had tried to seduce them all from their virtue, and they were resolved to go home and stay no longer in Kachikopa with such a man about the place. Then the brothers were exceedingly angry with Lingo, who they thought had deceived them with a pretence of virtue in refusing a wife, and they resolved to kill him. So they enticed him into the forest with a story of a great animal which had put them to flight and asked him to kill it, and there they shot him to death with their arrows and gouged out his eyes and played ball with them.

But the god Bhagwān became aware that Lingo was not praying to him as usual, and sent the crow Kageshwar to look for him. The crow came and reported that Lingo was dead, and the god sent him back with nectar to sprinkle it over the body and bring it to life again, which was done.

10. He releases the Gonds shut up in the cave and constitutes the tribe

Lingo then thought he had had enough of the four brothers, so he determined to go and find the other sixteen score Gonds who were imprisoned somewhere as the brothers had told him. The manner of his doing this may be told in Captain Forsyth’s version:51

And our Lingo redivivusWandered on across the mountains,Wandered sadly through the forestTill the darkening of the evening,Wandered on until the night fell.Screamed the panther in the forest,Growled the bear upon the mountain,And our Lingo then bethought himOf their cannibal propensities.Saw at hand the tree Niruda,Clambered up into its branches.Darkness fell upon the forest,Bears their heads wagged, yelled the jackalKolyal, the King of Jackals.Sounded loud their dreadful voicesIn the forest-shade primeval.Then the Jungle-Cock Gugotee,Mull the Peacock, Kurs the Wild Deer,Terror-stricken, screeched and shuddered,In that forest-shade primeval.But the moon arose at midnight,Poured her flood of silver radiance,Lighted all the forest arches,Through their gloomy branches slanting;Fell on Lingo, pondering deeplyOn his sixteen scores of Koitūrs.Then thought Lingo, I will ask herFor my sixteen scores of Koitūrs.‘Tell me, O Moon!’ said Lingo,‘Tell, O Brightener of the darkness!Where my sixteen scores are hidden.’But the Moon sailed onwards, upwards,And her cold and glancing moonbeamsSaid, ‘Your Gonds, I have not seen them.’And the Stars came forth and twinkledTwinkling eyes above the forest.Lingo said, “O Stars that twinkle!Eyes that look into the darkness,Tell me where my sixteen scores are.”But the cold Stars twinkling ever,Said, ‘Your Gonds, we have not seen them.’Broke the morning, the sky reddened,Faded out the star of morning,Rose the Sun above the forest,Brilliant Sun, the Lord of morning,And our Lingo quick descended,Quickly ran he to the eastward,Fell before the Lord of Morning,Gave the Great Sun salutation—‘Tell, O Sun!’ he said, ‘DiscoverWhere my sixteen scores of Gonds are.’But the Lord of Day reply made—“Hear, O Lingo, I a PilgrimWander onwards, through four watchesServing God, I have seen nothingOf your sixteen scores of Koitūrs.”Then our Lingo wandered onwardsThrough the arches of the forest;Wandered on until before himSaw the grotto of a hermit,Old and sage, the Black Kumāit,He the very wise and knowing,He the greatest of Magicians,Born in days that are forgotten,In the unremembered ages,Salutation gave and asked him—‘Tell, O Hermit! Great Kumāit!Where my sixteen scores of Gonds are.Then replied the Black Magician,Spake disdainfully in this wise—“Lingo, hear, your Gonds are assesEating cats, and mice, and bandicoots,Eating pigs, and cows, and buffaloes;Filthy wretches! wherefore ask me?If you wish it I will tell you.Our great Mahādeva caught them,And has shut them up securelyIn a cave within the bowelsOf his mountain Dewalgiri,With a stone of sixteen cubits,And his bulldog fierce Basmāsur;Serve them right, too, I consider,Filthy, casteless, stinking wretches!”And the Hermit to his grottoBack returned, and deeply ponderedOn the days that are forgotten,On the unremembered ages.But our Lingo wandered onwards,Fasting, praying, doing penance;Laid him on a bed of prickles,Thorns long and sharp and piercing.Fasting lay he devotee-like,Hand not lifting, foot not lifting,Eye not opening, nothing seeing.Twelve months long thus lay and fasted,Till his flesh was dry and withered,And the bones began to show through.Then the great god MahādevaFelt his seat begin to tremble,Felt his golden stool, all shakingFrom the penance of our Lingo.Felt, and wondered who on earthThis devotee was that was fastingTill his golden stool was shaking.Stepped he down from Dewalgiri,Came and saw that bed of pricklesWhere our Lingo lay unmoving.Asked him what his little game was,Why his golden stool was shaking.Answered Lingo, “Mighty Ruler!Nothing less will stop that shakingThan my sixteen scores of KoitūrsRendered up all safe and hurtlessFrom your cave in Dewalgiri.”Then the Great God, much disgusted,Offered all he had to Lingo,Offered kingdom, name, and riches,Offered anything he wished for,‘Only leave your stinking KoitūrsWell shut up in Dewalgiri.’But our Lingo all refusingWould have nothing but his Koitūrs;Gave a turn to run the thorns aLittle deeper in his midriff.Winced the Great God: “Very well, then,Take your Gonds—but first a favour.By the shore of the Black WaterLives a bird they call Black Bindo,Much I wish to see his young ones,Little Bindos from the sea-shore;For an offering bring these Bindos,Then your Gonds take from my mountain.”Then our Lingo rose and wandered,Wandered onwards through the forest,Till he reached the sounding sea-shore,Reached the brink of the Black Water,Found the Bingo birds were absentFrom their nest upon the sea-shore,Absent hunting in the forest,Hunting elephants prodigious,Which they killed and took their brains out,Cracked their skulls, and brought their brains toFeed their callow little Bindos,Wailing sadly by the sea-shore.Seven times a fearful serpent,Bhawarnāg the horrid serpent,Serpent born in ocean’s caverns,Coming forth from the Black Water,Had devoured the little Bindos—Broods of callow little BindosWailing sadly by the sea-shore—In the absence of their parents.Eighth this brood was. Stood our Lingo,Stood he pondering beside them—“If I take these little wretchesIn the absence of their parentsThey will call me thief and robber.No! I’ll wait till they come back here.”Then he laid him down and slumberedBy the little wailing Bindos.As he slept the dreadful serpent,Rising, came from the Black Water,Came to eat the callow Bindos,In the absence of their parents.Came he trunk-like from the waters,Came with fearful jaws distended,Huge and horrid, like a basketFor the winnowing of corn.Rose a hood of vast dimensionsO’er his fierce and dreadful visage.Shrieked the Bindos young and callow,Gave a cry of lamentation;Rose our Lingo; saw the monster;Drew an arrow from his quiver,Shot it swift into his stomach,Sharp and cutting in the stomach,Then another and another;Cleft him into seven pieces,Wriggled all the seven pieces,Wriggled backward to the water.But our Lingo, swift advancing,Seized the headpiece in his arms,Knocked the brains out on a boulder;Laid it down beside the Bindos,Callow, wailing, little Bindos.On it laid him, like a pillow,And began again to slumber.Soon returned the parent BindosFrom their hunting in the forest;Bringing brains and eyes of camelsAnd of elephants prodigious,For their little callow BindosWailing sadly by the sea-shore.But the Bindos young and callowBrains of camels would not swallow;Said—“A pretty set of parentsYou are truly! thus to leave usSadly wailing by the sea-shoreTo be eaten by the serpent—Bhawarnāg the dreadful serpent—Came he up from the Black Water,Came to eat us little Bindos,When this very valiant LingoShot an arrow in his stomach,Cut him into seven pieces—Give to Lingo brains of camels,Eyes of elephants prodigious.”Then the fond paternal BindoSaw the head-piece of the serpentUnder Lingo’s head a pillow,And he said, ‘O valiant Lingo,Ask whatever you may wish for.’Then he asked the little BindosFor an offering to the Great God,And the fond paternal Bindo,Much disgusted first refusing,Soon consented; said he’d go tooWith the fond maternal Bindo—Take them all upon his shoulders,And fly straight to Dewalgiri.Then he spread his mighty pinions,Took his Bindos up on one sideAnd our Lingo on the other.Thus they soared away togetherFrom the shores of the Black Water,And the fond maternal Bindo,O’er them hovering, spread an awningWith her broad and mighty pinionsO’er her offspring and our Lingo.By the forests and the mountainsSix months’ journey was it thitherTo the mountain Dewalgiri.Half the day was scarcely overEre this convoy from the sea-shoreLighted safe on Dewalgiri;Touched the knocker to the gatewayOf the Great God, Mahādeva.And the messenger NārāyanAnswering, went and told his master—“Lo, this very valiant Lingo!Here he is with all the Bindos,The Black Bindos from the sea-shore.”Then the Great God, much disgusted,Driven quite into a corner,Took our Lingo to the cavern,Sent Basmāsur to his kennel,Held his nose, and moved away theMighty stone of sixteen cubits;Called those sixteen scores of Gonds outMade them over to their Lingo.And they said, “O Father Lingo!What a bad time we’ve had of it,Not a thing to fill our belliesIn this horrid gloomy dungeon.”But our Lingo gave them dinner,Gave them rice and flour of millet,And they went off to the river,Had a drink, and cooked and ate it.The next episode is taken from a slightly different local version:

And while they were cooking their food at the river a great flood came up, but all the Gonds crossed safely except the four gods, Tekām, Markām, Pusām and Telengām.52 These were delayed because they had cooked their food with ghī which they had looted from the Hindu deities. Then they stood on the bank and cried out,

O God of the crossing,O Boundary God!Should you be here,Come take us across.Hearing this, the tortoise and crocodile came up to them, and offered to take them across the river. So Markām and Tekām sat on the back of the crocodile and Pusām and Telengām on the back of the tortoise, and before starting the gods made the crocodile and tortoise swear that they would not eat or drown them in the sea. But when they got to the middle of the river the tortoise and crocodile began to sink, with the idea that they would drown the Gonds and feed their young with them. Then the Gonds cried out, and the Raigīdhni or vulture heard them. This bird appears to be the same as the Bindo, as it fed its young with elephants. The Raigīdhni flew to the Gonds and took them up on its back and flew ashore with them. And in its anger it picked out the tongue of the crocodile and crushed the neck of the tortoise. And this is why the crocodile is still tongueless and the tortoise has a broken neck, which is sometimes inside and sometimes outside its shell. Both animals also have the marks of string on their backs where the Gond gods tied their necks together when they were ferried across. Thus all the Gonds were happily reunited and Lingo took them into the forest, and they founded a town there, which grew and prospered. And Lingo divided all the Gonds into clans and made the oldest man a Pardhān or priest and founded the rule of exogamy. He also made the Gond gods, subsequently described,53 and worshipped them with offerings of a calf and liquor, and danced before them. He also prescribed the ceremonies of marriage which are still observed, and after all this was done Lingo went to the gods.

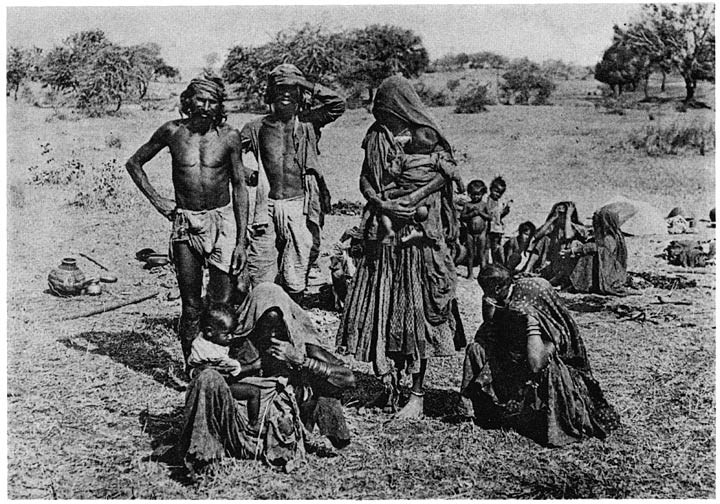

Gonds on a journey

(b) Tribal Subdivisions

11. Subcastes

Out of the Gond tribe, which, as it gave its name to a province, may be considered as almost a people, a number of separate castes have naturally developed. Among them are several occupational castes such as the Agarias or iron-workers, the Ojhas or soothsayers, Pardhāns or priests and minstrels, Solāhas or carpenters, and Koilabhutis or dancers or prostitutes. These are principally sprung from the Gonds, though no doubt with an admixture of other low tribes or castes. The Parjas of Bastar, now classed as a separate tribe, appear to represent the oldest Gond settlers, who were subdued by later immigrants of the race; while the Bhatras and Jhādi Telengas are of mixed descent from Gonds and Hindus. Similarly the Gowāri caste of cattle-graziers originated from the alliances of Gond and Ahīr graziers. The Mannewārs and Kolāms are other tribes allied to the Gonds. Many Hindu castes and also non-Aryan tribes living in contact with the Gonds have a large Gond element; of the former class the Ahīrs, Basors, Barhais and Lohārs, and of the latter the Baigas, Bhunjias and Khairwārs are instances.

Among the Gonds proper there are two aristocratic subdivisions, the Rāj-Gonds and Khatolas. According to Forsyth the Rāj-Gonds are in many cases the descendants of alliances between Rājpūt adventurers and Gonds. But the term practically comprises the landholding subdivision of the Gonds, and any proprietor who was willing to pay for the privilege could probably get his family admitted into the Rāj-Gond group. The Rāj-Gonds rank with the Hindu cultivating castes, and Brāhmans will take water from them. They sometimes wear the sacred thread. In the Telugu country the Rāj-Gond is known as Durla or Durlasattam. In some localities Rāj-Gonds will intermarry with ordinary Gonds, but not in others. The Khatola Gonds take their name from the Khatola state in Bundelkhand, which is said to have once been governed by a Gond ruler, but is no longer in existence. In Saugor they rank about equal with the Rāj-Gonds and intermarry with them, but in Chhindwāra it is said that ordinary Gonds despise them and will not marry with them or eat with them on account of their mixed descent from Gonds and Hindus. The ordinary Gonds in most Districts form one endogamous group, and are known as the Dhur or ‘dust’ Gonds, that is the common people. An alternative name conferred on them by the Hindus is Rāwanvansi or of the race of Rāwan, the demon king of Ceylon, who was the opponent of Rāma. The inference from this name is that the Hindus consider the Gonds to have been among the people of southern India who opposed the Aryan expedition to Ceylon, which is preserved in the legend of Rāma; and the name therefore favours the hypothesis that the Gonds came from the south and that their migration northward was sufficiently recent in date to permit of its being still remembered in tradition. There are several other small local subdivisions. The Koya Gonds live on the border of the Telugu country, and their name is apparently a corruption of Koi or Koitūr, which the Gonds call themselves. The Gaita are another Chānda subcaste, the word Gaite or Gaita really meaning a village priest or headman. Gattu or Gotte is said to be a name given to the hill Gonds of Chānda, and is not a real subcaste. The Darwe or Nāik Gonds of Chānda were formerly employed as soldiers, and hence obtained the name of Naīk or leader. Other local groups are being formed such as the Larhia or those of Chhattīsgarh, the Mandlāha of Mandla, the Lānjiha from Lānji and so on. These are probably in course of becoming endogamous. The Gonds of Bastar are divided into two groups, the Māria and the Muria. The Māria are the wilder, and are apparently named after the Mad, as the hilly country of Bastar is called. Mr. Hīra Lāl suggests the derivation of Muria from mur, the palās tree, which is common in the plains of Bastar, or from mur, a root. Both derivations must be considered as conjectural. The Murias are the Gonds who live in the plains and are more civilised than the Mārias. The descendants of the Rāja of Deogarh Bakht Buland, who turned Muhammadan, still profess that religion, but intermarry freely with the Hindu Gonds. The term Bhoi, which literally means a bearer in Telugu, is used as a synonym for the Gonds and also as an honorific title. In Chhindwāra it is said that only a village proprietor is addressed as Bhoi. It appears that the Gonds were used as palanquin-bearers, and considered it an honour to belong to the Kahār or bearer caste, which has a fairly good status.54