полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

Gond

[Bibliography.—The most important account of the Gond tribe is that contained in the Rev. Stephen Hislop’s Papers on the Aboriginal Tribes of the Central Provinces, published after his death by Sir R. Temple in 1866. Mr. Hislop recorded the legend of Lingo, of which an abstract has been reproduced. Other notices of the Gonds are contained in the ninth volume of General Cunningham’s Archaeological Survey Reports, Sir C. Grant’s Central Provinces Gazetteer of 1871 (Introduction), Colonel Ward’s Mandla Settlement Report (1868), Colonel Lucie Smith’s Chānda Settlement Report (1870), and Mr. C. W. Montgomerie’s Chhīndwāra Settlement Report (1900). An excellent monograph on the Bastar Gonds was contributed by Rai Bahādur Panda Baijnāth, Superintendent of the State, and other monographs by Mr. A. E. Nelson, C.S., Mandla; Mr. Ganga Prasād Khatri, Forest Divisional Officer, Betūl; Mr. J. Langhorne, Manager, Ahiri zamīndāri, Chānda; Mr. R. S. Thākur, tahsīldār, Bālāghāt; and Mr. Dīn Dayāl, Deputy Inspector of Schools, Nāndgaon State. Papers were also furnished by the Rev. A. Wood of Chānda; the Rev. H. J. Molony, Mandla; and Major W. D. Sutherland, I.M.S., Saugor. Notes were also collected by the writer in Mandla. Owing to the inclusion of many small details from the different papers it has not been possible to acknowledge them separately.]

(a) Origin and History

1. Numbers and distribution

Gond.—The principal tribe of the Dravidian family, and perhaps the most important of the non-Aryan or forest tribes in India. In 1911 the Gonds were three million strong, and they are increasing rapidly. The Kolis of western India count half a million persons more than the Gonds, and if the four related tribes Kol, Munda, Ho, and Santāl were taken together, they would be stronger by about the same amount. But if historical importance be considered as well as numbers, the first place should be awarded to the Gonds. Of the whole caste the Central Provinces contain 2,300,000 persons, Central India, and Bihār and Orissa about 235,000 persons each, and they are returned in small numbers from Assam, Madras and Hyderābād. The 50,000 Gonds in Assam are no doubt immigrant labourers on the tea-gardens.

2. Gondwāna

In the Central Provinces the Gonds occupy two main tracts. The first is the wide belt of broken hill and forest country in the centre of the Province, which forms the Satpūra plateau, and is mainly comprised in the Chhindwārā, Betūl, Seoni and Mandla Districts, with portions of several others adjoining them. And the second is the still wider and more inaccessible mass of hill ranges extending south of the Chhattīsgarh plain, and south-west down to the Godāvari, which includes portions of the three Chhattīsgarh Districts, the Bastar and Kanker States, and a great part of Chānda. In Mandla the Gonds form nearly half the population, and in Bastar about two-thirds. There is, however, no District or State of the Province which does not contain some Gonds, and it is both on account of their numbers and the fact that Gond dynasties possessed a great part of its area that the territory of the Central Provinces was formerly known as Gondwāna, or the country of the Gonds.37 The existing importance of the Central Provinces dates from recent years, for so late as 1853 it was stated before the Royal Asiatic Society that “at present the Gondwāna highlands and jungles comprise such a large tract of unexplored country that they form quite an oasis in our maps.” So much of this lately unexplored country as is British territory is now fairly well served by railways, traversed almost throughout by good roads, and provided with village schools at distances of five to ten miles apart, even in the wilder tracts.

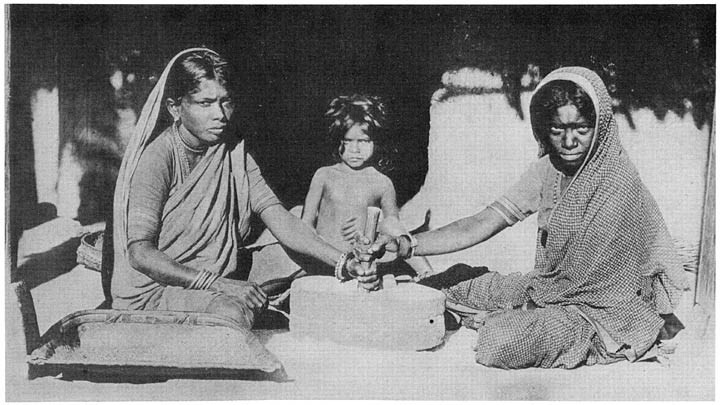

Gond women grinding corn

3. Derivation of name and origin of the Gonds

The derivation of the word Gond is uncertain. It is the name given to the tribe by the Hindus or Muhammadans, as their own name for themselves is Koitūr or Koi. General Cunningham considered that the name Gond probably came from Gauda, the classical term for part of the United Provinces and Bengal. A Benāres inscription relating to one of the Chedi kings of Tripura or Tewar (near Jubbulpore) states that he was of the Haihaya tribe, who lived on the borders of the Nerbudda in the district of the Western Gauda in the Province of Mālwa. Three or four other inscriptions also refer to the kings of Gauda in the same locality. Gauda, however, was properly and commonly used as the name of part of Bengal. There is no evidence beyond a few doubtful inscriptions of its having ever been applied to any part of the Central Provinces. The principal passage in which General Cunningham identifies Gauda with the Central Provinces is that in which the king of Gauda came to the assistance of the ruler of Mālwa against the king of Kanauj, elder brother of the great Harsha Vardhana, and slew the latter king in A.D. 605. But Mr. V. A. Smith holds that Gauda in this passage refers to Bengal and not to the Central Provinces;38 and General Cunningham’s argument on the locality of Gauda is thus rendered extremely dubious, and with it his derivation of the name Gond. In fact it seems highly improbable that the name of a large tribe should have been taken from a term so little used and known in this special application. Though in the Imperial Gazetteer39 the present writer reproduced General Cunningham’s derivation of the term Gond, it was there characterised as speculative, and in the light of the above remarks now seems highly improbable. Mr. Hislop considered that the name Gond was a form of Kond, as he spelt the name of the Khond tribe. He pointed out that k and g are interchangeable. Thus Gotalghar, the empty house where the village young men sleep, comes from Kotal, a led horse, and ghar, a house. Similarly, Koikopāl, the name of a Gond subtribe who tend cattle, is from Koi or Gond, and gopal, a cowherd. The name by which the Gonds call themselves is Koi or Koitūr, while the Khonds call themselves Ku, which word Sir G. Grierson considers to be probably related to the Gond name Koi. Further, he states that the Telugu people call the Khonds, Gond or Kod (Kor). General Cunningham points out that the word Gond in the Central Provinces is frequently or, he says, usually pronounced Gaur, which is practically the same sound as god, and with the change of G to K would become Kod. Thus the two names Gond and Kod, by which the Telugu people know the Khonds, are practically the same as the names Gond and God of the Gonds in the Central Provinces, though Sir G. Grierson does not mention the change of g to k in his account of either language. It seems highly probable that the designation Gond was given to the tribe by the Telugus. The Gonds speak a Dravidian language of the same family as Tamil, Canarese and Telugu, and therefore it is likely that they come from the south into the Central Provinces. Their route may have been up the Godāvari river into Chānda; from thence up the Indravati into Bastar and the hills south and east of the Chhattīsgarh plain; and up the Wardha and Wainganga to the Districts of the Satpūra Plateau. In Chānda, where a Gond dynasty reigned for some centuries, they would be in contact with the Telugus, and here they may have got their name of Gond, and carried it with them into the north and east of the Province. As already seen, the Khonds are called Gond by the Telugus, and Kandh by the Uriyas. The Khonds apparently came up more towards the east into Ganjam and Kālāhandi. Here the name of Gond or Kod, given them by the Telugus, may have been modified into Kandh by the Uriyas, and from the two names came the English corruption of Khond. The Khond and Gondi languages are now dissimilar. Still they present certain points of resemblance, and though Sir G. Grierson does not discuss their connection, it appears from his highly interesting genealogical tree of the Dravidian languages that Khond or Kui and Gondi are closely connected. These two languages, and no others, occupy an intermediate position between the two great branches sprung from the original Dravidian language, one of which is mainly represented by Telugu and the other by Tamil, Canarese and Malayālam.40 Gondi and Khond are shown in the centre as the connecting link between the two great branches. Gondi is more nearly related to Tamil and Khond to Telugu. On the Telugu side, moreover, Khond approaches most closely to Kolāmi, which is a member of the Telugu branch. The Kolāms are a tribe of Wardha and Berār, sometimes considered an offshoot of the Gonds; at any rate, it seems probable that they came from southern India by the same route as the Gonds. Thus the Khond language is intermediate between Gondi and the Kolāmi dialect of Wardha and Berār, though the Kolāms live west of the Gonds and the Khonds east. And a fairly close relationship between the three languages appears to be established. Hence the linguistic evidence appears to afford strong support to the view that the Khonds and Gonds may originally have been one tribe. Further, Mr. Hislop points out that a word for god, pen, is common to the Gonds and Khonds; and the Khonds have a god called Bura Pen, who might be the same as Bura Deo, the great god of the Gonds. Mr. Hislop found Kodo Pen and Pharsi Pen as Gond gods,41 while Pen or Pennu is the regular word for god among the Khonds. This evidence seems to establish a probability that the Gonds and Khonds were originally one tribe in the south of India, and that they obtained separate names and languages since they left their original home for the north. The fact that both of them speak languages of the Dravidian family, whose home is in southern India, makes it probable that the two tribes originally belonged there, and migrated north into the Central Provinces and Orissa. This hypothesis is supported by the traditions of the Gonds.

4. History of the Gonds

As stated in the article on Kol, it is known that Rājpūt dynasties were ruling in various parts of the Central Provinces from about the sixth to the twelfth centuries. They then disappear, and there is a blank till the fourteenth century or later, when Gond kingdoms are found established at Kherla in Betūl, at Deogarh in Chhīndwara, at Garha-Mandla,42 including the Jubbulpore country, and at Chānda, fourteen miles from Bhāndak. It seems clear, then, that the Hindu dynasties were subverted by the Gonds after the Muhammadan invasions of northern India had weakened or destroyed the central powers of the Hindus, and prevented any assistance being afforded to the outlying settlements. There is some reason to suppose that the immigration of the Gonds into the Central Provinces took place after the establishment of these Hindu kingdoms, and not before, as is commonly held.43 But the point must at present be considered doubtful. There is no reason however to doubt that the Gonds came from the south through Chānda and Bastar. During the fourteenth century and afterwards the Gonds established dynasties at the places already mentioned in the Central Provinces. For two or three centuries the greater part of the Province was governed by Gond kings. Of their method of government in Narsinghpur, Sleeman said: “Under these Gond Rājas the country seems for the most part to have been distributed among feudatory chiefs, bound to attend upon the prince at his capital with a stipulated number of troops, to be employed wherever their services might be required, but to furnish little or no revenue in money. These chiefs were Gonds, and the countries they held for the support of their families and the payment of their troops and retinue little more than wild jungles. The Gonds seem not to have been at home in open country, and as from the sixteenth century a peaceable penetration of Hindu cultivators into the best lands of the Province assumed large dimensions, the Gonds gradually retired to the hill ranges on the borders of the plains.” The headquarters of each dynasty at Mandla, Garha, Kherla, Deogarh and Chānda seem to have been located in a position strengthened for defence either by a hill or a great river, and adjacent to an especially fertile plain tract, whose produce served for the maintenance of the ruler’s household and headquarters establishment. Often the site was on other sides bordered by dense forest which would afford a retreat to the occupants in case it fell to an enemy. Strong and spacious forts were built, with masonry tanks and wells inside them to provide water, but whether these buildings were solely the work of the Gonds or constructed with the assistance of Hindu or Muhammadan artificers is uncertain. But the Hindu immigrants found Gond government tolerant and beneficent. Under the easy eventless sway of these princes the rich country over which they ruled prospered, its flocks and herds increased, and the treasury filled. So far back as the fifteenth century we read in Firishta that the king of Kherla, who, if not a Gond himself, was a king of the Gonds, sumptuously entertained the Bāhmani king and made him rich offerings, among which were many diamonds, rubies and pearls. Of the Rāni Dūrgavati of Garha-Mandla, Sleeman said: “Of all the sovereigns of this dynasty she lives most in the page of history and in the grateful recollections of the people. She built the great reservoir which lies close to Jubbulpore, and is called after her Rāni Talao or Queen’s pond; and many other highly useful works were formed by her about Garha.” When the castle of Chaurāgarh was sacked by one of Akbar’s generals in 1564, the booty found, according to Firishta, comprised, independently of jewels, images of gold and silver and other valuables, no fewer than a hundred jars of gold coin and a thousand elephants. Of the Chānda rulers the Settlement officer who has recorded their history wrote that, “They left, if we forget the last few years, a well-governed and contented kingdom, adorned with admirable works of engineering skill and prosperous to a point which no aftertime has reached. They have left their mark behind them in royal tombs, lakes and palaces, but most of all in the seven miles of battlemented stone wall, too wide now for the shrunk city of Chānda within it, which stands on the very border-line between the forest and the plain, having in front the rich valley of the Wardha river, and behind and up to the city walls deep forest extending to the east.” According to local tradition the great wall of Chānda and other buildings, such as the tombs of the Gond kings and the palace at Junona, were built by immigrant Telugu masons of the Kāpu or Munurwār castes. Another excellent rule of the Gond kings was to give to any one who made a tank a grant of land free of revenue of the land lying beneath it. A large number of small irrigation tanks were constructed under this inducement in the Wainganga valley, and still remain. But the Gond states had no strength for defence, as was shown when in the eighteenth century Marātha chiefs, having acquired some knowledge of the art of war and military training by their long fighting against the Mughals, cast covetous eyes on Gondwāna. The loose tribal system, so easy in time of peace, entirely failed to knit together the strength of the people when united action was most required, and the plain country fell before the Marātha armies almost without a struggle. In the strongholds, however, of the hilly ranges which hem in every part of Gondwāna the chiefs for long continued to maintain an unequal resistance, and to revenge their own wrongs by indiscriminate rapine and slaughter. In such cases the Marātha plan was to continue pillaging and harassing the Gonds until they obtained an acknowledgment of their supremacy and the promise, at least, of an annual tribute. Under this treatment the hill Gonds soon lost every vestige of civilisation, and became the cruel, treacherous savages depicted by travellers of this period. They regularly plundered and murdered stragglers and small parties passing through the hills, while from their strongholds, built on the most inaccessible spurs of the Satpūras, they would make a dash into the rich plains of Berār and the Nerbudda valley, and after looting and killing all night, return straight across country to their jungle fortresses, guided by the light of a bonfire on some commanding peak.44 With the pacification of the country and the introduction of a strong and equable system of government by the British, these wild marauders soon settled down and became the timid and inoffensive labourers which they now are.

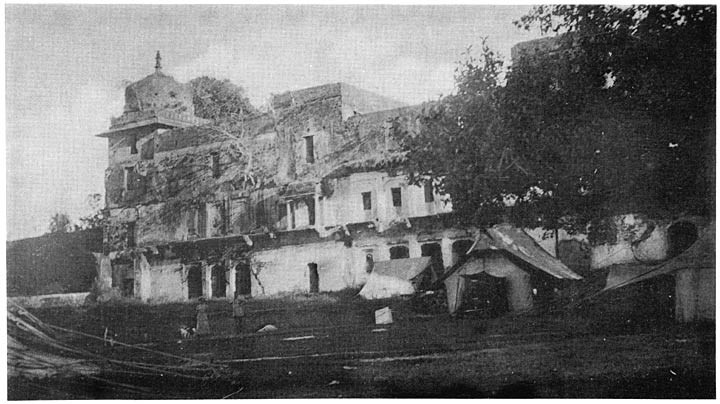

Palace of the Gond kings of Garha-Mandla at Rāmnagar

5. Mythica traditions. Story of Lingo

Mr. Hislop took down from a Pardhān priest a Gond myth of the creation of the world and the origin of the Gonds, and their liberation from a cave, in which they had been shut up by Siva, through the divine hero Lingo. General Cunningham said that the exact position of the cave was not known, but it would seem to have been somewhere in the Himalayas, as the name Dhawalgiri, which means a white mountain, is mentioned. The cave, according to ordinary Gond tradition, was situated in Kachikopa Lohāgarh or the Iron Valley in the Red Hill. It seems clear from the story itself that its author was desirous of connecting the Gonds with Hindu mythology, and as Siva’s heaven is in the Himalayas, the name Dhawalgiri, where he located the cave, may refer to them. It is also said that the cave was at the source of the Jumna. But in Mr. Hislop’s version the cave where all the Gonds except four were shut up is not in Kachikopa Lohāgarh, as the Gonds commonly say; but only the four Gonds who escaped wandered to this latter place and dwelt there. And the story does not show that Kachikopa Lohāgarh was on Mount Dhawalgiri or the Himalayas, where it places the cave in which the Gonds were shut up, or anywhere near them. On the contrary, it would be quite consonant with Mr. Hislop’s version if Kachikopa Lohāgarh were in the Central Provinces. It may be surmised that in the original Gond legend their ancestors really were shut up in Kachikopa Lohāgarh, but not by the god Siva. Very possibly the story began with them in the cave in the Iron Valley in the Red Hill. But the Hindu who clearly composed Mr. Hislop’s version wished to introduce the god Siva as a principal actor, and he therefore removed the site of the cave to the Himalayas. This appears probable from the story itself, in which, in its present form, Kachikopa Lohāgarh plays no real part, and only appears because it was in the original tradition and has to be retained.45 But the Gonds think that their ancestors were actually shut up in Kachikopa Lohāgarh, and one tradition puts the site at Pachmarhi, whose striking hill scenery and red soil cleft by many deep and inaccessible ravines would render it a likely place for the incident. Another version locates Kachikopa Lohāgarh at Dārekasa in Bhandāra, where there is a place known as Kachagarh or the iron fort. But Pachmarhi is perhaps the more probable, as it has some deep caves, which have always been looked upon as sacred places. The point is of some interest, because this legend of the cave being in the Himalayas is adduced as a Gond tradition that their ancestors came from the north, and hence as supporting the theory of the immigration of the Dravidians through the north-west of India. But if the view now suggested is correct, the story of the cave being in the Himalayas is not a genuine Gond tradition at all, but a Hindu interpolation. The only other ground known to the writer for asserting that the Gonds believed their ancestors to have come from the north is that they bury their dead with the feet to the north. There are other obvious Hindu accretions in the legend, as the saintly Brāhmanic character of Lingo and his overcoming the gods through fasting and self-torture, and also the fact that Siva shut up the Gonds in the cave because he was offended by their dirty habits and bad smell. But the legend still contains a considerable quantity of true Gond tradition, and though somewhat tedious, it seems necessary to give an abridgment of Mr. Hislop’s account, with reproduction of selected passages. Captain Forsyth also made a modernised poetical version,46 from which one extract is taken. Certain variations from another form of the legend obtained in Bastar are included.

6. Legend of the creation

In the beginning there was water everywhere, and God was born in a lotus-leaf and lived alone. One day he rubbed his arm and from the rubbing made a crow, which sat on his shoulder; he also made a crab, which swam out over the waters. God then ordered the crow to fly over the world and bring some earth. The crow flew about and could find no earth, but it saw the crab, which was supporting itself with one leg resting on the bottom of the sea. The crow was very tired and perched on the crab’s back, which was soft so that the crow’s feet made marks on it, which are still visible on the bodies of all crabs at present. The crow asked the crab where any earth could be found. The crab said that if God would make its body hard it would find some earth. God said he would make part of the crab’s body hard, and he made its back hard, as it still remains. The crab then dived to the bottom of the sea, where it found Kenchna, the earth-worm. It caught hold of Kenchna by the neck with its claws and the mark thus made is still to be seen on the earth-worm’s neck. Then the earth-worm brought up earth out of its mouth and the crab brought this to God, and God scattered it over the sea and patches of land appeared. God then walked over the earth and a boil came on his hand, and out of it Mahādeo and Pārvati were born.

7. Creation of the Gonds and their imprisonment by Mahādeo

From Mahādeo’s urine numerous vegetables began to spring up. Pārvati ate of these and became pregnant and gave birth to eighteen threshing-floors47 of Brāhman gods and twelve threshing-floors of Gond gods. All the Gonds were scattered over the jungle. They behaved like Gonds and not like good Hindus, with lamentable results, as follows:48

Hither and thither all the Gonds were scattered in the jungle.

Places, hills, and valleys were filled with these Gonds.

Even trees had their Gonds. How did the Gonds conduct themselves?

Whatever came across them they must needs kill and eat it;

They made no distinction. If they saw a jackal they killed

And ate it; no distinction was observed; they respected not antelope, sāmbhar and the like.

They made no distinction in eating a sow, a quail, a pigeon,

A crow, a kite, an adjutant, a vulture,

A lizard, a frog, a beetle, a cow, a calf, a he- and she-buffalo,

Rats, bandicoots, squirrels—all these they killed and ate.

So began the Gonds to do. They devoured raw and ripe things;

They did not bathe for six months together;

They did not wash their faces properly, even on dunghills they would fall down and remain.

Such were the Gonds born in the beginning. A smell was spread over the jungle

When the Gonds were thus disorderly behaved; they became disagreeable to Mahādeva,

Who said: “The caste of the Gonds is very bad;

I will not preserve them; they will ruin my hill Dhawalgiri.”

Mahādeo then determined to get rid of the Gonds. With this view he invited them all to a meeting. When they sat down Mahādeo made a squirrel from the rubbings of his body and let it loose in the middle of the Gonds. All the Gonds at once got up and began to chase it, hoping for a meal. They seized sticks and stones and clods of earth, and their unkempt hair flew in the wind. The squirrel dodged about and ran away, and finally, directed by Mahādeo, ran into a large cave with all the Gonds after it. Mahādeo then rolled a large stone to the mouth of the cave and shut up all the Gonds in it. Only four remained outside, and they fled away to Kachikopa Lohāgarh, or the Iron Cave in the Red Hill, and lived there. Meanwhile Pārvati perceived that the smell of the Gonds, which had pleased her, had vanished from Dhawalgiri. She desired it to be restored and commenced a devotion. For six months she fasted and practised austerities. Bhagwān (God) was swinging in a swing. He was disturbed by Pārvati’s devotion. He sent Nārāyan (the sun) to see who was fasting. Nārāyan came and found Pārvati and asked her what she wanted. She said that she missed her Gonds and wanted them back. Nārāyan told Bhagwān, who promised that they should be given back.