полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

Thuiya, Bhuiya,550 Dharti Māta, Thākur Deo, Bhainsa Sur; khūb paida kariye Mahārāj;

that is, they invoke Mother Earth, Thākur Deo, the corn-god, and Bhainsāsur, the buffalo demon, to give them good crops; and as they say this they throw a handful of grain in the air in the name of each god.

13. Witchcraft

“Among the Hos,” Colonel Dalton states, “all disease in men or animals is attributed to one of two causes—the wrath of some evil spirit who has to be appeased, or the spell of some witch or sorcerer who should be destroyed or driven out of the land. In the latter case a sokha or witch-finder is employed to ascertain who has cast the spell, and various methods of divination are resorted to. In former times the person denounced and all his family were put to death in the belief that witches breed witches and sorcerers. The taint is in the blood. When, during the Mutiny, Singhbhūm District was left for a short time without officers, a terrible raid was made against all who had been suspected for years of dealing with the evil one, and the most atrocious murders were committed. Young men were told off for the duty by the elders; neither age nor sex were spared. When order was restored, these crimes were brought to light, and the actual perpetrators punished; and since then we have not only had no recurrence of witch murders, but the superstition itself is dying out in the Kolhān.” Mr. H. C. Streatfeild states that among the Mundas witches used to be hung head downwards from a pīpal tree over a slow fire, the whole village dancing as they were gradually roasted, but whether this ceremony was purely vindictive or had any other significance there is nothing to show.551

14. Funeral rites

The Hos of Chota Nāgpur were accustomed to place large slabs of stone as tombstones over their graves, and a collection of these massive gravestones indelibly marks the site of every Ho or Mundāri village, being still found in parts of the country where there have been no Kols for ages. In addition to this slab, a megalithic monument is set up to the deceased in some conspicuous spot outside the village; the pillars vary in height from five or six to fifteen feet, and apparently fragments of rock of the most fantastic shape are most favoured. All the clothes, ornaments and agricultural implements of the dead man were buried with the body. The funeral rites were of a somewhat touching character:552 “When all is ready, a funeral party collects in front of the deceased’s house, three or four men with very deep-toned drums, and a group of about eight young girls. The chief mourner comes forth, carrying the bones exposed on a decorated tray, and behind him the girls form two rows, carrying empty or broken pitchers or battered brass vessels, while the men with drums bring up the rear. The procession advances with a ghostly dancing movement, slow and solemn as a minuet, in time to the beat of the deep-toned drums, not straight forward, but mysteriously gliding—now right, now left, now marking time, all in the same mournful cadence. In this manner the remains are taken to the house of every friend and relative of the deceased within a circle of a few miles, and to every house in the village. As the procession approaches each house in the manner described, the inmates all come out, and the tray having been placed on the ground at their door, they kneel over it and mourn. The bones are also thus conveyed to all his favourite haunts, the fields he cultivated, the grove he planted, the tank he excavated, the threshing-floor where he worked with his people, the Akhāra or dancing-arena where he made merry with them, and each spot which is hallowed with reminiscences of the deceased draws forth fresh tears.” In Sambalpur553 the dead body of a Munda is washed in wine before interment, and a mark of vermilion is made on the forehead. The mourners drink wine sitting by the grave. They then bathe, and catch a small fish and roast it on a fire, smearing their hands with oil and warming them at the fire. It would appear that this last rite is a purification of the hands after contact with the dead body, but whether the fish is meant to represent the deceased and the roasting of it is a substitute for the rite of cremation is not clear. During the eight days of mourning the relatives abstain from flesh-meat, but they eat fish. The Kols of Jubbulpore now bury or burn the dead, and observe mourning exactly like ordinary Hindus.

15. Inheritance

Succession among the Mundas passes to sons only. Failing these, the property goes to the father or brothers if any. At partition the eldest son as a rule gets a slightly larger share than the other sons, a piece of land, and in well-to-do families a yoke of plough cattle, or only a bullock or a goat, and sometimes a bundle of paddy weighing from 10 to 16 maunds.554 Partition cannot usually be made till the youngest son is of age. Daughters get no share in the inheritance, and are allotted among the sons just like live-stock. Thus if a man dies leaving three sons and three daughters and thirty head of cattle, on a division each son would get ten head of cattle and one sister; but should there be only one sister, they wait till she marries and divide the bride-price. A father may, however, in his lifetime make presents of cash or movables to a daughter, though not of land. It is doubtful whether these rules still obtain among the Hinduised Kols.

16. Physical appearance

“The Mundas,” Colonel Dalton states, “are one of the finest of the aboriginal tribes. The men average something like 5 feet 6 inches, and many of them are remarkably well developed and muscular. Their skin is of the darkest brown, almost black in many cases, and their features coarse, with broad flat noses, low foreheads and thick lips, presenting as a rule a by no means prepossessing appearance. The women are often more pleasing, the coarseness of the features being less accentuated or less noticeable on account of the extreme good-nature and happy carelessness that seldom fail to mark their countenance. They are fond of ornament, and a group of men and girls fully decked out for a festival makes a fine show. Every ornament in the shape of bead necklace, silver collar, bracelet, armlet and anklet would seem to have been brought out for the occasion. The head-dress is the crowning point of the turn-out. The long black hair is gathered up in a big coil, most often artificially enlarged, the whole being fastened at the right-hand side of the back of the head just on a level with and touching the right ear. In this knot are fastened all sorts of ornaments of brass and silver, and surmounting it, stuck in every available space, are gay plumes of feathers that nod and wave bravely with the movements of the dance. The ears are distorted almost beyond recognition by huge earrings that pierce the lobe and smaller ones that ornament them all round.” In Mandla women are tattooed with the figure of a man or a man on horseback, and on the legs behind also with the figure of a man. They are not tattooed on the face. Men are never tattooed.

17. Dances

“Dancing is the inevitable accompaniment of every gathering, and they have a great variety suitable to the special times and seasons. The motion is slow and graceful, a monotonous sing-song being kept up all through. The steps are in perfect time and the action wonderfully even and regular. This is particularly noticeable in some of the variations of the dances representing the different seasons and the necessary acts of cultivation that each brings with it. In one the dancers bending down make a motion with their hands as though they were sowing the grain, keeping step with their feet all the time. Then come the reaping of the crop and the binding of the sheaves, all done in perfect time and rhythm, and making with the continuous droning of the voices a quaint and picturesque performance.” In the Central Provinces the Kols now dance the Karma dance of the Gonds, but they dance it in more lively fashion. The step consists simply in advancing or withdrawing one foot and bringing the other up or back beside it. The men and women stand opposite each other in two lines, holding hands, and the musicians alternately face each line and advance and retreat with them. Then the lines move round in a circle with the musicians in the centre.

18. Social rules and offences

Munda boys are allowed to eat food cooked by other castes, except the very lowest, until they are married, and girls until they let their hair grow long, which is usually at the age of six or seven. After this they do not take food as a tribe from any other caste, even a Brāhman, though some subtribes accept it from certain castes as the Telis (oil-pressers) and Sundis or liquor-vendors. In Jubbulpore the Kols take food from Kurmis, Dhīmars and Ahīrs. The Mundas will eat almost all kinds of flesh, including tigers and pigs, while in Raigarh they consider monkey as a delicacy, hunting these animals with dogs. In the Central Provinces they have generally abjured beef, in deference to Hindu prejudice, and sometimes refuse field-mice, to which the Khonds and Gonds are very partial. Neither Kols nor Mundas are, however, considered impure and the barber and washerman will work for them. In Sambalpur a woman is finally expelled from caste for a liaison with one of the impure Gāndas, Ghasias or Doms, and a man is expelled for taking food from a woman of these castes, but adultery with her may be expiated by a big feast. Other offences are much the same as among the Hindus. A woman who gets her ear torn through where it is pierced is put out of caste for six months or a year and has to give two feasts on readmission.

19. The caste panchāyat

In Mandla the head of the panchāyat is known as Gaontia, a name for a village headman, and he is always of the Bargaiya sept, the office being usually hereditary. When a serious offence is committed the Gaontia fixes a period of six months to a year for the readmission of the culprit, or the latter begs for reinstatement when he has obtained the materials for the penalty feast. A feast for the whole Rautele subcaste will entail 500 seers or nearly 9 cwt. of kodon, costing perhaps Rs. 30, and they say there would not be enough left for a cold breakfast for the offender’s family in the morning. When a man has a petition to make to the Gaontia, he folds his turban round his neck, leaving the head bare, takes a piece of grass in his mouth, and with four prominent elders to support him goes to the Gaontia and falls at his feet. The others stand on one leg behind him and the Gaontia asks them for their recommendation. Their reverence for the caste panchāyat is shown by their solemn form of oath, ‘Sing-Bonga on high and the Panch on earth.’555 The Kols of Jubbulpore and Mandla are now completely conforming to Hindu usage and employ Brāhmans for their ceremonies. They are most anxious to be considered as good Hindus and ape every high-caste custom they get hold of. On one occasion I was being carried on a litter by Kol coolies and accompanied by a Rājpūt chuprāssie and was talking to the Kols, who eagerly proclaimed their rigid Hindu observances. Finally the chuprāssie said that Brāhmans and Rājpūts must have three separate brushes of date-palm fibre for their houses, one to sweep the cook-room which is especially sacred, one for the rest of the house, and one for the yard. Lying gallantly the Kols said that they also kept three palm brushes for cleaning their houses, and when it was pointed out that there were no date-palms within several miles of their village, they said they sent periodical expeditions to the adjoining District to bring back fibre for brushes.

20. Names

Colonel Dalton notes that the Kols, like the Gonds, give names to their children after officers visiting the village when they are born. Thus Captain, Major, Doctor are common names in the Kolhān. Mr. Mazumdār gives an instance of a Kol servant of the Rāja of Bāmra who greatly admired some English lamp-chimneys sent for by the Rāja and called his daughter ‘Chimney.’ They do not address any relative or caste-man by his name if he is older than themselves, but use the term of relationship to a relative and to others the honorific title of Gaontia.

21. Occupation

The Mundāri language has no words for the village trades nor for the implements of cultivation, and so it may be concluded that prior to their contact with the Hindus the Mundas lived on the fruits and roots of the forests and the pursuit of game and fish. Now, however, they have taken kindly to several kinds of labour. They are much in request on the Assam tea-gardens owing to their good physique and muscular power, and they make the best bearers of dhoolies or palanquins. Kol bearers will carry a dhoolie four miles an hour as against the best Gond pace of about three, and they shake the occupant less. They also make excellent masons and navvies, and are generally more honest workers than the other jungle tribes. A Munda seldom comes into a criminal court.

22. Language

The Kols of the Central Provinces have practically abandoned their own language, Mundāri being retained only by about 1000 persons in 1911. The Kols and Mundas now speak the Hindu vernacular current in the tracts where they reside. Mundāri, Santāli, Korwa and Bhumij are practically all forms of one language which Sir G. Grierson designates as Kherwāri.556

Kolām

1. General notice of the tribe

Kolām.557—A Dravidian tribe residing principally in the Wūn tāluk of the Yeotmāl District. They number altogether about 25,000 persons, of whom 23,000 belong to Wūn and the remainder to the adjoining tracts of Wardha and Hyderābād. They are not found elsewhere. The tribe are generally considered to be akin to the Gonds558 on the authority of Mr. Hislop. He wrote of them: “The Kolāms extend all along the Kandi Konda or Pindi Hills on the south of the Wardha river and along the table-land stretching east and north of Mānikgad and thence south to Dāntanpalli, running parallel to the western bank of the Prānhīta. The Kolāms and the common Gonds do not intermarry, but they are present at each other’s nuptials and eat from each other’s hand. Their dress is similar, but the Kolām women wear fewer ornaments, being generally content with a few black beads of glass round their neck. Among their deities, which are the usual objects of Gond adoration, Bhīmsen is chiefly honoured.” Mr. Hislop was, however, not always of this opinion, because he first excluded the Kolāms from the Gond tribes and afterwards included them.559 In Wardha they are usually distinguished from the Gonds. They have a language of their own, called after them Kolāmi. Sir G. Grierson560 describes it as, “A minor dialect of Berār and the Central Provinces which occupies a position like that of Gondi between Canarese, Tamil and Telugu. The so-called Kolāmi, the Bhīli spoken in the Pusad tāluk of Bāsim and the so-called Naiki of Chānda agree in so many particulars that they can almost be considered as one and the same dialect. They are closely related to Gondi. The points in which they differ from that language are, however, of sufficient importance to make it necessary to separate them from that form of speech. The Kolāmi dialect differs widely from the language of the neighbouring Gonds. In some points it agrees with Telugu, in other characteristics with Canarese and connected forms of speech. There are also some interesting points of analogy with the Todā dialect of the Nīlgiris, and the Kolāms must, from a philological point of view, be considered as the remnants of an old Dravidian tribe who have not been involved in the development of the principal Dravidian languages, or of a tribe who have not originally spoken a Dravidian form of speech.”

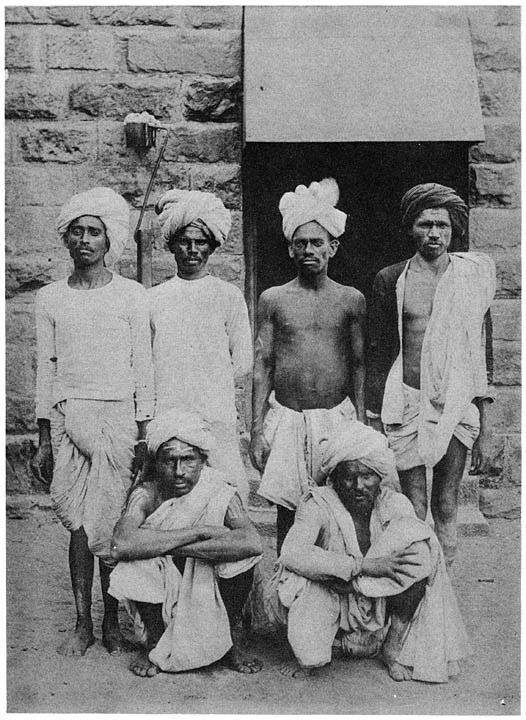

Group of Kōlams

The family names of the tribe also are not Gondi, but resemble those of Marātha castes. Out of fifty sept names recorded, only one, Tekām, is found among the Gonds. “All their songs and ballads,” Colonel Mackenzie says, “are borrowed from the Marāthas: even their women when grinding corn sing Marāthi songs.” In Wūn their dress and appearance resembles that of the Kunbis, but in some respects they retain very primitive customs. Colonel Mackenzie states that until recently in Berār they had the practice of capturing husbands for women who would otherwise have gone unwedded, this being apparently a survival of the matriarchate. It does not appear that the husbands so captured were ever unphilosophical enough to rebel under the old regime, though British enlightenment has taught them otherwise. Widows and widowers were exempt from capture and debarred from capturing. In view of the connection mentioned by Sir G. Grierson between the Kolāmi dialect and that of the Todās of the Nīlgiri hills who are a small remnant of an ancient tribe and still practise polyandry, Mr. Hīra Lāl suggests that the Kolāms may be connected with the Kolas, a tribe akin to the Todās561 and as low in the scale of civilisation, who regard the Kolamallai hills as their original home.562 He further notes that the name of the era by which the calendar is reckoned on the Malabar coast is Kolamba. In view of Sir G. Grierson’s statement that the Kolāmi dialect is the same as that of the Nāik Gonds of Chānda it may be noted that the headman of a Kolām village is known as Nāik, and it is possible that the Kolāms may be connected with the so-called Nāik Gonds.

2. Marriage

The Kolāms have no subtribes, but are divided for purposes of marriage into a number of exogamous groups. The names of these are in the Marāthi form, but the tribe do not know their meaning. Marriage between members of the same group is forbidden, and a man may not marry two sisters. Marriage is usually adult, and neither a betrothal nor a marriage can be concluded in the month of Poush (December), because in this month ancestors are worshipped. Colonel Mackenzie states that marriages should be celebrated on Wednesdays and Saturdays at sundown, and Monday is considered a peculiarly inauspicious day. If a betrothal, once contracted, is broken, a fine of five or ten rupees must be paid to the caste-fellows together with a quantity of liquor. Formerly, as stated above, the tribe sometimes captured husbands, and they still have a curious method of seizing a wife when the father cannot procure a mate for his son. The latter attended by his comrades resorts to the jungle where his wife-elect is working in company with her female relations and friends. It is a custom of the tribe that the sexes should, as a rule, work in separate parties. On catching sight of her the bridegroom pursues her, and unless he touches her hand before she gets back to her village, his friends will afford him no assistance. If he can lay hold of the girl a struggle ensues between the two parties for her possession, the girl being sometimes only protected by women, while on other occasions her male relatives hear of the fray and come to her assistance. In the latter case a fight ensues with sticks, in which, however, no combatant may hit another on the head. If the girl is captured the marriage is subsequently performed, and even if she is rescued the matter is often arranged by the payment of a few rupees to the girl’s father. Nowadays the whole affair tends to degenerate into a pretence and is often arranged beforehand by the parties. The marriage ceremony resembles that of the Kunbis except that the bridegroom takes the bride on his lap and their clothes are tied together in two places. After the ceremony each of the guests takes a few grains of rice, and after touching the feet, knees and shoulders of the bridal couple with the rice, throws it over his own back. The idea may be to remove any contagion of misfortune or evil spirits who may be hovering about them. A widow can remarry only with her parents’ consent, but if she takes a fancy to a man and chooses to enter his house with a pot of water on her head he cannot turn her out. A man cannot marry a widow unless he has been regularly wedded once to a girl, and once having espoused a widow by what is known as the pāt ceremony, he cannot again go through a proper marriage. A couple who wish to be divorced must go before the caste panchāyat or committee with a pot of liquor. Over this is laid a dry stick and the couple each hold an end of it. The husband then addresses his wife as sister in the presence of the caste-fellows, and the wife her husband as brother; they break the stick and the divorce is complete.

3. Disposal of the dead

The tribe bury their dead, and observe mourning for one to five days in different localities. The spirits of deceased ancestors are worshipped on any Monday in the month of Poush. The mourner goes and dips his head into a tank or stream, and afterwards sacrifices a fowl on the bank, and gives a meal to the caste-fellows. He then has the hair of his face and head shaved. Sons inherit equally, and if there are no sons the property devolves on daughters.

4. Religion and superstitions

The Kolāms, Colonel Mackenzie states, recognise no god as a principle of beneficence in the world; their principal deities are Sīta, to whom the first-fruits of the harvest are offered, and Devi who is the guardian of the village, and is propitiated with offerings of goats and fowls to preserve it from harm. She is represented by two stones set up in the centre of the village when it is founded. They worship their implements of agriculture on the last day of Chait (April), applying turmeric and vermilion to them. In May they collect the stumps of juāri from a field, and, burning them to ashes, make an offering of the same articles. They have a curious ceremony for protecting the village from disease. All the men go outside the village and on the boundary at the four points pointing north-east, north-west and opposite place four stones known as bandi, burying a fowl beneath each stone. The Nāik or headman then sacrifices a goat and other fowls to Sīta, and placing four men by the stones, proceeds to sprinkle salt all along the boundary line, except across one path on which he lays his stick. He then calls out to the men that the village is closed and that they must enter it only by that path. This rule remains in force throughout the year, and if any stranger enters the village by any other than the appointed route, they consider that he should pay the expenses of drawing the boundary circuit again. But the rule is often applied only to carts, and relaxed in favour of travellers on foot. The line marked with salt is called bandesh, and it is believed that wild animals cannot cross it, while they are prevented from coming into the village along the only open road by the stick of the Nāik. Diseases also cannot cross the line. Women during their monthly impurity are made to live in a hut in the fields outside the boundary line. The open road does not lead across the village, but terminates at the chauri or meeting-house.

5. Social position

Though the Kolāms retain some very primitive customs, those of Yeotmāl, as already stated, are hardly distinguishable from the Kunbis or Hindu cultivators. Colonel Mackenzie notes that they are held to be lower than the Gonds, because a Kolām will take food from a Gond, but the latter will not return the compliment. They will eat the flesh of rats, tigers, snakes, squirrels and of almost any animals except dogs, donkeys and jackals. In another respect they are on a level with the lowest aborigines, as some of them do not use water to clean their bodies after performing natural functions, but only leaves. Yet they are not considered as impure by the Hindus, are permitted to enter Hindu temples, and hold themselves to be defiled by the touch of a Mahār or a Māng. A Kolām is forbidden to beg by the rules of the tribe, and he looks down on the Mahārs and Māngs, who are often professional beggars. In Wardha, too, the Kolāms will not collect dead-wood for sale as fuel.