полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

3. Religion

They worship the ordinary Hindu gods and especially Devi, to whom they offer female kids. During the months of Baisākh and Jeth (April–June) those living in Betūl and Chhindwāra make a pilgrimage to the Nāg Deo or cobra god, who is supposed to have his seat somewhere on the border of the two Districts. Every third year they also take their cattle outside the village, and turning their faces in the direction of the Nāg Deo sprinkle a little water and kill goats and fowls. They worship the Patel Deo or spirit of the deceased mālguzār of the village only on the occasion of marriages. They consider the service of the village headman to be their traditional occupation besides agriculture, and they therefore probably pay this special compliment to the spirit of their employer. They worship their implements of husbandry on some convenient day, which must be a Wednesday or a Sunday, after they have sown the spring crops. Those who grow sugarcane offer a goat or a cocoanut to the crop before it is cut, and a similar offering is made to the stock of grain after harvest, so that its bulk may not decrease. They observe the ordinary festivals, and like other Hindus cease to observe one on which a death has occurred in the family, until some happy event such as the birth of a child, or even of a calf, supervenes on the same day. Unmarried children under seven and persons dying of smallpox, snake-bite or cholera are buried, and others are either buried or burnt according to the convenience of the family. Males are placed on the pyre or in the grave on their faces and females on their backs, with their feet pointing to the south in each case. In some places the corpse is buried stark naked, and in others with a piece of cloth wrapped round it, and two pice are usually placed in the grave to buy the site. When a corpse is burnt the head is touched with a bamboo before it is laid on the funeral pyre, by way of breaking it in and allowing the soul to escape if it has not already done so. For three days the mourners place food, water and tobacco in cups for the disembodied soul. Mourning is observed for children for three days and for adults from seven to ten days. During this period the mourners refrain from luxurious food such as flesh, turmeric, vegetables, milk and sweets; they do not wear shoes, nor change their clothes, and males are not shaved until the last day of mourning. Balls of rice are then offered to the dead, and the caste people are feasted. Oblations of water are offered to ancestors in the month of Kunwār (September-October).

4. Social customs

The caste do not admit outsiders. In the matter of food they eat flesh and fish, but abstain from liquor and from eating fowls, except in the Marātha country. They will take pakka food or that cooked without water from Gūjars, Rāghuvansis and Lodhis. In the Nāgpur country, where the difference between katcha and pakka food is not usually observed, they will not take it from any but Marātha Brāhmans. Abīrs and Dhīmars are said to eat with them, and the northern Brāhmans will take water from them. They have a caste panchāyat or committee with a hereditary president called Sethia, whose business it is to eat first when admitting a person who has been put out of caste. Killing a cat or a squirrel, selling a cow to a butcher, growing hemp or selling shoes are offences which entail temporary excommunication from caste. A woman who commits adultery with a man of another caste is permanently excluded. The Kirārs are tall in stature and well and stoutly built. They have regular features and are generally of a fair colour. They are regarded as quarrelsome and untruthful, and as tyrannical landlords. As agriculturists they are supposed to be of encroaching tendencies, and the proverbial prayer attributed to them is, “O God, give me two bullocks, and I shall plough up the common way.” Another proverb quoted in Mr. Standen’s Betūl Settlement Report, in illustration of their avarice, is “If you put a rupee between two Kirārs, they become like mast buffaloes in Kunwār.” The men always wear turbans, while the women may be distinguished in the Marātha country by their adherence to the dress of the northern Districts. Girls are tattooed on the back of their hands before they begin to live with their husbands. A woman may not name her husband’s elder brother or even touch his clothes or the vessels in which he has eaten food. They are not distinguished for cleanliness.

5. Occupation

Agriculture and the service of the village headman are the traditional occupations of Kirārs. In Nāgpur they are considered to be very good cultivators, but they have no special reputation in the northern Districts. About a thousand of them are landowners, and the large majority are tenants. They grow garden crops and sugarcane, but abstain from the cultivation of hemp.

Kohli

1. General notice

Kohli.—A small caste of cultivators found in the Marāthi-speaking tracts of the Wainganga Valley, comprised in the Bhandāra and Chānda Districts. They numbered about 26,000 persons in 1911. The Kohlis are a notable caste as being the builders of the great irrigation reservoirs or tanks, for which the Wainganga Valley is celebrated. The water is used for irrigating rice and sugarcane, the latter being the favourite crop of the Kohlis. The origin of the caste is somewhat doubtful. The name closely resembles that of the Koiri caste of market-gardeners in northern India; and the terms Kohiri and Kohli are used there as variations of the caste name Koiri. The caste themselves have a tradition that they were brought to Bhandāra from Benāres by one of the Gond kings of Chānda on his return from a visit to that place;528 and the Kohlis of Bhandāra say that their first settlement in the Central Provinces was at Lānji, which lies north of Bhandāra in Bālāghāt. But on the other hand all that is known of their language, customs, and sept or family names points to a purely Marātha origin, the caste being in all these respects closely analogous to the Kunbis. The Settlement Officer of Chānda, Colonel Lucie Smith, stated that they thought their forefathers came from the south. They tie their head-cloths in a similar fashion to the Gāndlis, who are oilmen from the Telugu country. If they belonged to the south of India they might be an offshoot from the well-known Koli tribe of Bombay, and this hypothesis appears the more probable. As a general rule castes from northern India settling in the Marātha country have not completely abandoned their ancestral language and customs even after a residence of several centuries. In the case of such castes as the Panwārs and Bhoyars their foreign extraction can be detected at once; and if the Kohlis had come from Hindustān the rule would probably hold good with them. On the other hand the Kolis have in some parts of Bombay now taken to cultivation and closely resemble the Kunbis. In Satāra it is said529 that they associate and occasionally eat with Kunbis, and their social and religious customs resemble those of the Kunbi caste. They are quiet, orderly, settled and hard-working. Besides fishing they work ferries along the Krishna, are employed in villages as water-carriers, and grow melons in river-beds with much skill. The Kolis of Bombay are presumably the same tribe as the Kols of Chota Nāgpur, and they probably migrated to Gujarāt along the Vindhyan plateau, where they are found in considerable numbers, and over the hills of Rājputāna and Central India. The Kols are one of the most adaptive of all the non-Aryan tribes, and when they reached the sea they may have become fishermen and boatmen, and practised these callings also in rivers. From plying on rivers they might take to cultivating melons and garden-crops on the stretches of silt left uncovered in their beds in the dry season, which is the common custom of the boating and fishing castes. And from this, as seen in Satāra, some of them attained to regular cultivation and, modelling themselves on the Kunbis, came to have nearly the same status. They may thus have migrated to Chānda and Bhandāra with the Kunbis, as their language and customs would indicate, and retaining their preference for irrigated and garden-crops have become expert growers of sugarcane. The description which has been received of the Kohlis of Bhandāra would be rather favourable than otherwise to the hypothesis of their ultimate origin from the Kol tribe, allowing for their having acquired the Marātha language and customs from a lengthened residence in Bombay. It has been mentioned above that the Kohlis have a legend of their ancestors having come from Benāres, but this story appears to be not infrequently devised as a means of obtaining increased social estimation, Benāres being the principal centre of orthodox Hinduism. Thus the Dāngris, a small caste of vegetable- and melon-growers who are certainly an offshoot of the Kunbis, and therefore of Marātha extraction, have the same story. As regards the tradition of the Bhandāra Kohlis that their first settlement was at Lānji, this may well have been the case even though they came from the south, as Lānji was an important place and a centre of administration under the Marāthas. It is probable, however, that they first came to Chānda and from here spread north to Lānji, as, if they had entered Bhandāra through Wardha and Nāgpur, some of them would probably have remained in these Districts.

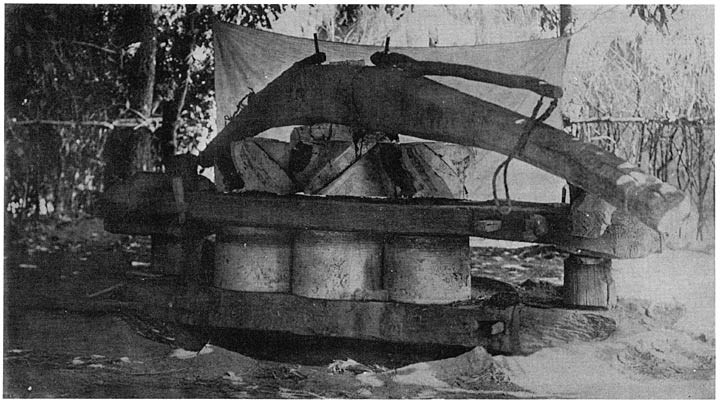

Old type of sugarcane mill

2. Marriage and other customs

The Kohlis have no subcastes. They are divided into the usual exogamous groups or septs with the object of preventing marriages between relations, and these have Marāthi names of the territorial or titular type. Among them may be mentioned Handifode (one who breaks a cooking vessel), Sahre (from shahar, a town), Nāgpure (from Nāgpur), Shende (from shend, cowdung), Parwate (from parwat, mountain), Hatwāde (an obstinate man), Mungus-māre (one who killed a mongoose), Pustode (one who broke a bullock’s tail), and so on. Marriage within the sept is prohibited. A brother’s daughter may be married to his sister’s son, but not vice versa. Girls are usually wedded before arriving at adolescence, more especially as there is a great demand for brides. Like other castes engaged in spade cultivation, the Kohlis marry two or more wives when they can afford it, a wife being a more willing servant than a hired labourer, apart from the other advantages. If his wives do not get on together, the Kohli gives them separate huts in his courtyard, where each lives and cooks her meals for herself. He will also allot them separate tasks, assigning to one the care of his household affairs, to another the watching of his sugarcane plot, and so on. If he does this successfully the wives are kept well at work and have not time to quarrel. It is said that whenever a Kohli has a bountiful harvest he looks out for another wife. This naturally leads to a scarcity of women and the payment of a substantial bride-price. The recognised amount is Rs. 30, but this is only formal, and from Rs. 50 to Rs. 150 may be given according to the attractions of the girl, the largest sum being paid for a woman of full age who can go and live with her husband at once. As a consequence of this state of things poor men are sometimes unable to get wives at all. Though they pay highly for their wives the Kohlis are averse to extravagant expenditure on weddings, and all marriages in a village are generally celebrated on the same day once a year, the number of guests at each being thus necessarily restricted. The officiating Brāhman ascends the roof of a house and, after beating a brass dish to warn the parties, repeats the marriage texts as the sun goes down. At this moment all the couples place garlands of flowers on each other’s shoulders, each bridegroom ties the mangal-sūtram or necklace of black beads round his bride’s neck, and the weddings are completed. The bride’s brother winds a thread round the marriage crowns of the couple and is given two rupees for untying it. The services of a Brāhman are not indispensable, and an elder of the caste may officiate as priest. Next day the barber and washerman take the bridegroom and bride in their arms and dance, holding them, to the accompaniment of music, while the women throw red rose-powder over the couple. At their weddings the Kohlis make models in wood of a Chamār’s rāmpi or knife and khurpa or scraper, this custom perhaps indicating some connection with the Chamārs; or it may have arisen simply on account of the important assistance rendered by the Chamār to the cultivation of sugarcane, in supplying the mot or leather bag for raising water from the well. After the wedding is over a string of hemp from a cot is tied round the necks of the pair, and their maternal uncles then run and offer it at the shrine of Marai Māta, the goddess of cholera. Widows with any remains of youth or personal attractions always marry again, the ceremony being held at midnight according to the customary ritual of the Marātha Districts.530 Sometimes the husband does not attend at all, and the widow is united to a sword or dagger as representing him. Otherwise the widow may be conducted to her new husband’s house by five other widows, and in this case they halt at a stream by the way and the bangles and beads are broken from off her neck and wrists. On account, perhaps, of the utility of their wives, and the social temptations which beset them from being continually abroad at work, the Kohlis are lenient to conjugal offences, and a woman going wrong even with an outsider will be taken back by her husband and only a trifling punishment imposed by the caste. A Kohli can also keep a woman of any other caste, except of those regarded as impure, without incurring any censure. Divorce is very seldom resorted to and involves severe penalties to both parties. As among the Panwārs, a wife retains any property she may bring to her husband and her wedding gifts at her own disposal, this separate portion being known as khamora. The caste burn their dead when they can afford it, placing the head of the corpse to the north on the pyre. The bodies of those who have died from cholera or smallpox are buried. Like the Panwārs it is the custom of the Kohlis on bathing after a funeral to have a meal of cakes and sugar on the river-bank, a practice which is looked down on by orthodox Hindus. After a month or so the deceased person is considered to be united to the ancestors, and when he was the head of the family his successor is inducted to the position by the presentation of a new head-cloth and a silver bangle. The bereaved family are then formally escorted to the weekly market and are considered to have resumed their regular social relations. The Kohlis revere the ordinary Hindu deities, and on the day of Dasahra they worship their axe, sickle and ploughshare by washing them and making an offering of rice, flowers and turmeric. The axe is no doubt included because it serves to cut the wood for fencing the sugarcane garden.

3. The Kohlis as tank-builders

The Kohlis were the builders of the great tanks of the Bhandāra District. The most important of these are Nawegaon with an area of five square miles and a circumference of seventeen, and Seoni, over seven miles round, while smaller tanks are counted by thousands. Though the largest are the work of the Kohlis, many of the others have been constructed by the Panwārs of this tract, who have also much aptitude for irrigation. Built as they were without technical engineering knowledge, the tanks form an enduring monument to the native ability and industry of these enterprising cultivators. “Working,” Mr. Danks remarks,531 “without instruments, unable even to take a level, finding out their mistakes by the destruction of the works they had built, ever repairing, reconstructing, altering, they have raised in every village a testimony to their wisdom, their industry and their perseverance.” Although Nawegaon tank has a water area of seven square miles, the combined length of the two artificial embankments is only 760 yards, and this demonstrates the great skill with which the site has been selected. At some of the tanks men are stationed day and night during the rainy season to see if the embankment is anywhere weakened by the action of the water, and in that case to give the alarm to the village by beating a drum. The Nawegaon tank is said to have been built at the commencement of the eighteenth century by one Kolu Patel Kohli. As might be expected, Kolu Patel has been deified as Kolāsur Deo, and his shrine is on one of the peaks surrounding the tank. Seven other peaks are known as the Sāt Bahini or ‘Seven Sisters,’ and it is said that these deities assisted Kolu in building the tank, by coming and working on the embankment at night when the labourers had left. Some whitish-yellow stones on Kolāsur’s hill are said to be the baskets of the Seven Sisters in which they carried earth. “The Kohli,” Mr. Napier states,532 “sacrifices all to his sugarcane, his one ambition and his one extravagance being to build a large reservoir which will contain water for the irrigation of his sugarcane during the long, hot months.” Each rates the other according to the size of his tank and the strength of its embankment. Under the Gond kings a man who built a tank received a grant of the fields lying below it either free of revenue or on a very light assessment. Such grants were known as Tukm, and were probably a considerable incentive to tank-building. Unfortunately sugarcane, formerly a most profitable crop, has been undersold by the canal- and tank-irrigated product of northern India, and at present scarcely repays cultivation.

4. Agricultural customs

The Kohli villages are managed on a somewhat patriarchal system, and the dealings between proprietors and cultivators are regulated by their own custom without much regard to the rules imposed by Government. Mr. Napier says of them:533 “The Kohlis are very good landlords as a general rule; but in their dealings with their tenants and their labourers follow their own customs, while the provisions of the Tenancy Act often remain in abeyance. They admit no tenant right in land capable of being irrigated for sugarcane, and change the tenants as they please; and in many villages a large number of the labourers are practically serfs, being fed, clothed and married by their employers, for whom they and their children work all their lives without any fixed wages. These customs are acquiesced in by all parties, and, so far as I could learn, there was no discontent. They have a splendid caste discipline, and their quarrels are settled expeditiously by their panchāyats or committees without reference to courts of law.”

5. General characteristics

In appearance and character the Kohlis cannot be said to show much trace of distinction. The men wear a short white bandi or coat, and a small head-cloth only three feet long. This is often scarcely more than a handkerchief which tightly covers the crown, and terminates in knots, inelegant and cheap. The women wear glass bangles only on the left hand and brass or silver ones on the right, no doubt because glass ornaments would interfere with their work and get broken. Their cloth is drawn over the left shoulder instead of the right, a custom which they share with Gonds, Kāpewārs and Buruds. In appearance the caste are generally dirty. They are ignorant themselves and do not care that their children should be educated. Their custom of polygamy leads to family quarrels and excessive subdivision of property; thus in one village, Ashti, the proprietary right is divided into 192 shares. On this account they are seldom well-to-do. Their countenances are of a somewhat inferior type and generally dark in colour. In character they are peaceful and amenable, and have the reputation of being very respectful to Government officials, who as a consequence look on them with favour. ‘Their heart is good,’ a tahsīldār534 of the Bhandāra District remarked. If a guest comes to a Kohli, the host himself offers to wash his feet, and if the guest be a Brāhman, will insist on doing so. They eat flesh and fowls, but abstain from liquor. In social status they are on a level with the Mālis and a little below the regular cultivating castes.

Kol

[This article is based mainly on Colonel Dalton’s classical description of the Mundas and Hos in the Ethnology of Bengal and on Sir H. Risley’s article on Munda in The Tribes and Castes of Bengal. Extracts have also been made from Mr. Sarat Chandra Roy’s exhaustive account in The Mundas and their Country (Calcutta, 1912). Information on the Mundas and Kols of the Central Provinces has been collected by Mr. Hīra Lāl in Raigarh and by the author in Mandla, and a monograph has been furnished by Mr. B. C. Mazumdār, Pleader, Sambalpur. It should be mentioned that most of the Kols of the Central Provinces have abandoned the old tribal customs and religion described by Colonel Dalton, and are rapidly coming to resemble an ordinary low Hindu caste.]

1. General notice. Strength of the Kols in India

Kol, Munda, Ho.—A great tribe of Chota Nāgpur, which has given its name to the Kolarian family of tribes and languages. A part of the District of Singhbhūm near Chaibāsa is named the Kolhān as being the special home of the Larka Kols, but they are distributed all over Chota Nāgpur, whence they have spread to the United Provinces, Central Provinces and Central India. It seems probable also that the Koli tribe of Gujarāt may be an offshoot of the Kols, who migrated there by way of Central India. If the total of the Kols, Mundas and Hos or Larka Kols be taken together they number about a million persons in India. The real strength of the tribe is, however, much greater than this. As shown in the article on that tribe, the Santāls are a branch of the Kols, who have broken off from the parent stock and been given a separate designation by the Hindus. They numbered two millions in 1911. The Bhumij (400,000) are also probably a section of the tribe. Sir H. Risley535 states that they are closely allied to if not identical with the Mundas. In some localities they intermarry with the Mundas and are known as Bhumij Munda.536 If the Kolis also be taken as an offshoot of the Kol tribe, a further addition of nearly three millions is made to the tribes whose parentage can be traced to this stock. There is little doubt also that other Kolarian tribes, as the Kharias, Khairwars, Korwas and Korkus, whose tribal languages closely approximate to Mundāri, were originally one with the Mundas, but have been separated for so long a period that their direct connection can no longer be proved. The disintegrating causes, which have split up what was originally one into a number of distinct tribes, are probably no more than distance and settlement in different parts of the country, leading to cessation of intermarriage and social intercourse. The tribes have then obtained some variation in the original name or been given separate territorial or occupational designations by the Hindus and their former identity has gradually been forgotten.

2. Names of the tribe

“The word Kol is probably the Santāli hār, a man. This word is used under various forms, such as har, hāra, ho and koro by most Munda tribes in order to denote themselves. The change of r to l is familiar and does not give rise to any difficulty.”537 The word Korku is simply a corruption of Kodaku, young men, and there is every probability that the Hindus, hearing the Kol tribe call themselves hor or horo, may have corrupted the name to a form more familiar to themselves. An alternative derivation from the Sanskrit word kola, a pig, is improbable. But it is possible, as suggested by Sir G. Grierson, that after the name had been given, its Sanskrit meaning of pig may have added zest to its employment by the Hindus. The word Munda, Sir H. Risley states, is the common term employed by the Kols for the headman of a village, and has come into general use as an honorific title, as the Santāls call themselves Mānjhi, the Gonds Bhoi, and the Bhangis and other sweepers Mehtar. Munda, like Mehtar, originally a title, has become a popular alternative name for the caste. In Chota Nāgpur those Kols who have partly adopted Hinduism and become to some degree civilised are commonly known as Munda, while the name Ho or Larka Kol is reserved for the branch of the tribe in Singhbhūm who, as stated by Colonel Dalton, “From their jealous isolation for so many years, their independence, their long occupation of one territory, and their contempt for all other classes that come in contact with them, especially the Hindus, probably furnish the best illustration, not of the Mundāris in their present state, but of what, if left to themselves and permanently located, they were likely to become. Even at the present day the exclusiveness of the old Hos is remarkable. They will not allow aliens to hold land near their villages; and indeed if it were left to them no strangers would be permitted to settle in the Kolhān.”