полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

It is this branch of the tribe whose members have come several times into contact with British troops, and on account of their bravery and warlike disposition they are called the Larka or fighting Kols. The Mundas on the other hand appear now to be a very mixed group. The list of their subcastes given538 by Sir H. Risley includes the Khangār, Kharia, Mahali, Oraon and Savar Mundas, all of which are the names of separate tribes, now considered as distinct, though with the exception of the Oraons they were perhaps originally offshoots of the Kols or akin to them; while the Bhuinhār or landholders and Nāgvansi or Mundas of the royal house are apparently the aristocracy of the original tribe. It would appear possible from the list of sub-tribes already given that the village headmen of other tribes, having adopted the designation of Munda and intermarried with other headmen so as to make a superior group, have in some cases been admitted into the Munda tribe, which may enjoy a higher rank than other tribes as the Rāja of Chota Nāgpur belongs to it; but it is also quite likely that these groups may have simply arisen from the intermarriages of Mundas with other tribes, alliances of this sort being common. The Kols of the Central Provinces probably belong to the Munda tribe of Chota Nāgpur, and not to the Hos or Larka Kols, as the latter would be less likely to emigrate. But quite a separate set of subcastes is found here, which will be given later.

3. Origin of the Kolarian tribes

The Munda languages have been shown by Sir G. Grierson to have originated from the same source as those spoken in the Indo-Pacific islands and the Malay Peninsula. “The Mundas, the Mon-Khmer, the wild tribes of the Malay Peninsula and the Nicobarese all use forms of speech which can be traced back to a common source though they mutually differ widely from each other.”539 It would appear therefore that the Mundas, the oldest known inhabitants of India, perhaps came originally from the south-east, the islands of the Indian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, unless India was their original home and these countries were colonised from it.

Sir E. Gait states: “Geologists tell us that the Indian Peninsula was formerly cut off from the north of Asia by sea, while a land connection existed on the one side with Madagascar and on the other with the Malay Archipelago; and though there is nothing to show that India was then inhabited we know that it was so in palaeolithic times, when communication was probably still easier with the countries to the north-east and south-west than with those beyond the Himalayas.”540 In the south of India, however, no traces of Munda languages remain at present, and it seems therefore necessary to conclude that the Mundas of the Central Provinces and Chota Nāgpur have been separated from the tribes of Malaysia who speak cognate languages for an indefinitely long period, or else that they did not come through southern India to these countries, but by way of Assam and Bengal or by sea through Orissa. There is good reason to believe from the names of places and from local tradition that the Munda tribes were once spread over Bihār and parts of the Ganges valley; and if the Kolis are an offshoot of the Kols, as is supposed, they also penetrated across Central India to the sea in Gujarāt and the hills of the Western Ghāts. It is presumed that the advance of the Aryans or Hindus drove the Mundas from the open country to the seclusion of the hills and forests. The Munda and Dravidian languages are shown by Sir G. Grierson to be distinct groups without any real connection.

4. The Kolarians and Dravidians

Though the physical characteristics of the two sets of tribes display no marked points of difference, it has been generally held by ethnologists who know them that they represent two distinct waves of immigration, and the absence of connection between their languages bears out this view. It has always been supposed that the Mundas were in the country of Chota Nāgpur and the Central Provinces first, and that the Dravidians, the Gonds, Khonds and Oraons came afterwards. The grounds for this view are the more advanced culture of the Dravidians; the fact that where the two sets of tribes are in contact those of the Munda group have been ousted from the more open and fertile country, of which according to tradition they were formerly in possession; and the practice of the Gonds and other Dravidian tribes of employing the Baigas, Bhuiyas and other Munda tribes for their village priests, which is an acknowledgment that the latter as the earlier residents have a more familiar acquaintance with the local deities, and can solicit their favour and protection with more prospect of success. Such a belief is the more easily understood when it is remembered that these deities are not infrequently either the human ancestors of the earliest residents or the local animals and plants from which they supposed themselves to be descended.

5. Date of the Dravidian immigration

The Dravidian languages, Gondi, Kurukh and Khond, are of one family with Tamil, Telugu, Malayālam and Canarese, and their home is the south of India. As stated541 by Sir E. Gait, there is at present no evidence to show that the Dravidians came to southern India from any other part of the world, and for anything that is known to the contrary the languages may have originated there. The existence of the small Brahui tribe in Baluchistān, who speak a Dravidian language but have no physical resemblance to other Dravidian races, cannot be satisfactorily explained, but as he points out this is no reason for holding that the whole body of speakers of Dravidian languages entered India from the north-west, and, with the exception of this small group of Brahuis, penetrated to the south of India and settled there without leaving any traces of their passage.

The Dravidian languages occupy a large area in Madras, Mysore and Hyderābād, and they extend north into the Central Provinces and Chota Nāgpur, where they die out, practically not being found west and north of this tract. As the languages are more highly developed and the culture of their speakers is far more advanced in the south, it is justifiable to suppose, pending evidence to the contrary, that the south is their home and that they have spread thence as far north as the Central Provinces. The Gonds and Oraons too have stories to the effect that they came from the south. It has hitherto been believed, at least in the Central Provinces, that both the Gonds and Baigas have been settled in this territory for an indefinite period, that is, from prior to any Aryan or Hindu immigration. Mr. H. A. Crump, however, has questioned this assumption. He points out that the Baiga tribe have entirely lost their own language and speak a dialect of Chhattīsgarhi Hindi in Mandla, while half the Gonds still speak Gondi. If the Baigas and Gonds were settled here together before the arrival of any Hindus, how is it that the Baigas do not speak Gondi instead of Hindi? A comparison of the caste and language tables of the census of 1901 shows that several of the Munda tribes have entirely lost their own language, among these being the Binjhwār, Baiga, Bhaina, Bhuiya, Bhumij, Chero and Khairwār, and the Bhīls and Kolis if these are held to be Munda tribes. None of these tribes have adopted a Dravidian language, but all speak corrupt forms of the current Aryan vernaculars derived from Sanskrit. The Mundas and Hos themselves with the Kharias, Santāls and Korkus retain Munda languages. On the other hand a half of the Gonds, nearly all the Oraons and three-fourths of the Khonds still preserve their own Dravidian speech. It would therefore seem that the Munda tribes who speak Aryan vernaculars must have been in close contact with Hindu peoples at the time they lost their own language and not with Gonds or Oraons. In the Central Provinces it is known that Rājpūt dynasties were ruling in Jubbulpore from the sixth to the twelfth century, in Seoni about the sixth century and in Bhāndak near Chānda from an early period as well as at Ratanpur in Chhattīsgarh. From about the twelfth century these disappear and there is a blank till the fourteenth century or later, when Gond kingdoms are found established at Kherla in Betūl, at Deogarh in Chhindwāra, at Garha-Mandla542 including the Jubbulpore country, and at Chānda fourteen miles from Bhāndak. It seems clear then that the Hindu dynasties were subverted by the Gonds after the Muhammadan invasions of northern India had weakened or destroyed the central powers of the Hindus and prevented any assistance being afforded to the outlying settlements. But it seems prima facie more likely that the Hindu kingdoms of the Central Provinces should have been destroyed by an invasion of barbarians from without rather than by successful risings of their own subjects once thoroughly subdued. The Haihaya Rājpūt dynasty of Ratanpur was the only one which survived, all the others being supplanted by Gond states. If then the Gond incursion was subsequent to the establishment of the old Hindu kingdoms, its probable date may be placed from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries, the subjugation of the greater part of the Province being no doubt a gradual affair. In favour of this it may be noted that some recollection still exists of the settlement of the Oraons in Chota Nāgpur being later than that of the Mundas, while if it had taken place long before this time all tradition of it would probably have been forgotten. In Chhindwāra the legend still remains that the founder of the Deogarh Gond dynasty, Jātba, slew and supplanted the Gaoli kings Ransur and Ghansur, who were previously ruling on the plateau. And the Bastar Rāj-Gond Rājas have a story that they came from Warangal in the south so late as the fourteenth century, accompanied by the ancestors of some of the existing Bastar tribes. Jadu Rai, the founder of the Gond-Rājpūt dynasty of Garha-Mandla, is supposed to have lived near the Godāvari. A large section of the Gonds of the Central Provinces are known as Rāwanvansi or of the race of Rāwan, the demon king of Ceylon, who was conquered by Rāma. The Oraons also claim to be descended from Rāwan.543 This name and story must clearly have been given to the tribes by the Hindus, and the explanation appears to be that the Hindus considered the Dravidian Gonds and Oraons to have been the enemy encountered in the Aryan expedition to southern India and Ceylon, which is dimly recorded in the legend of Rāma. On the other hand the Bhuiyas, a Munda tribe, call themselves Pāwan-ka-put or Children of the Wind, that is of the race of Hanumān, who was the Son of the Wind; and this name would appear to show, as suggested by Colonel Dalton, that the Munda tribes gave assistance to the Aryan expedition and accompanied it, an alliance which has been preserved in the tale of the exploits of Hanumān and his army of apes. Similarly the name of the Rāmosi caste of Berār is a corruption of Rāmvansi or of the race of Rāma; and the Rāmosis appear to be an offshoot of the Bhīls or Kolis, both of whom are not improbably Munda tribes. A Hindu writer compared the Bhīl auxiliaries in the camp of the famous Chalukya Rājpūt king Sidhrāj of Gujarāt to Hanumān and his apes, on account of their agility.544 These instances seem to be in favour of the idea that the Munda tribes assisted the Aryans, and if this were the case it would appear to be a legitimate inference that at the same period the Dravidian tribes were still in southern India and not mixed up with the Munda tribes in the Central Provinces and Chota Nāgpur as at present. Though the evidence is perhaps not very strong, the hypothesis, as suggested by Mr. Crump, that the settlement of the Gonds in the Central Provinces is comparatively recent and subsequent to the early Rājpūt dynasties, is well worth putting forward.

6. Strength of the Kols in the Central Provinces

In the Central Provinces the Kols and Mundas numbered 85,000 persons in 1911. The name Kol is in general use except in the Chota Nāgpur States, but it seems probable that the Kols who have immigrated here really belong to the Munda tribe of Chota Nāgpur. About 52,000 Kols, or nearly a third of the total number, reside in the Jubbulpore District, and the remainder are scattered over all Districts and States of the Province.

7. Legend of origin

The Kol legend of origin is that Sing-Bonga or the Sun created a boy and a girl and put them together in a cave to people the world; but finding them to be too innocent to give hope of progeny he instructed them in the art of making rice-beer, which inflames the passions, and in course of time they had twelve sons and twelve daughters. The divine origin ascribed by the Kols, in common with other peoples, to their favourite liquor may be noticed. The children were divided into pairs, and Sing-Bonga set before them various kinds of food to choose for their sustenance before starting out into the world; and the fate of their descendants depended on their choice. Thus the first and second pairs took the flesh of bullocks and buffaloes, and from them are descended the Kols and Bhumij; one pair took shell-fish and became Bhuiyas, two pairs took pigs and were the ancestors of the Santāls, one pair took vegetables only and originated the Brāhman and Rājpūt castes, and other pairs took goats and fish, from whom the various Sūdra castes are sprung. One pair got nothing, and seeing this the Kol pair gave them of their superfluity and the descendants of these became the Ghasias, who are menials in Kol villages and supported by the cultivators. The Larka Kols attribute their strength and fine physique to the fact that they eat beef. When they first met English soldiers in the beginning of the nineteenth century the Kols were quickly impressed by their wonderful fighting powers, and finding that the English too ate the flesh of bullocks, paid them the high compliment of assigning to them the same pair of ancestors as themselves. The Nāgvansi Rājas of Chota Nāgpur say that their original ancestor was a snake-god who assumed human form and married a Brāhman’s daughter. But, like Lohengrin, the condition of his remaining a man was that he should not disclose his origin, and when he was finally brought to satisfy the incessant curiosity of his wife, he reverted to his first shape, and she burned herself from remorse. Their child was found by some wood-cutters lying in the forest beneath a cobra’s extended hood, and was brought up in their family. He subsequently became king, and his seven elder brothers attended him as banghy-bearers when he rode abroad. The Mundas are said to be descended from the seven brothers, and their sign-manual is a kawar or banghy.545 Hence the Rājas of Chota Nāgpur regard the Mundas as their elder brothers, and the Rānis veil their faces when they meet a Munda as to a husband’s elder brother. The probable explanation of the story is that the Hos or Mundas, from whom the kings are sprung, were a separate section of the tribe who subdued the older Mundas. In memory of their progenitor the Nāgvansi Rājas wear a turban folded to resemble the coils of a snake with a projection over the brow for its head.546

8. Tribal subdivisions

The subcastes of the Kols in the Central Provinces differ entirely from those in Chota Nāgpur. Of the important subcastes here the Rautia and Rautele take their name from Rāwat, a prince, and appear to be a military or landholding group. In Chota Nāgpur the Rautias are a separate caste, holding land. The Rautia Kols practise hypergamy with the Rauteles, taking their daughters in marriage but not giving daughters. They will eat with Rauteles at wedding feasts only and not on any other occasion. The Thākuria, from thākur, a lord, are said to be the progeny of Rājpūt fathers and Kol mothers; and the Kagwaria to be named from kagwār, an offering made to ancestors in the month of Kunwār. The Desāha, from desh, native country, belong principally to Rewah. In some localities Bharias, Savars and Khairwārs are found who call themselves Kols and appear to be included in the tribe. The Bharias may be an offshoot of the Bhar tribe of northern India. It has already been seen that several groups of other tribes have been amalgamated with the Mundas of Chota Nāgpur, probably in a great measure from intermarriage, and a similar fusion seems to have occurred in the Central Provinces. Intermarriage between the different subtribes, though nominally prohibited, not infrequently takes place, and a girl forming a liaison with a man of another division may be married to him and received into it. The Rautias, however, say that they forbid this practice.

9. Totemism

The Mandla Kols have a number of totemistic septs. The Bargaiyan are really called after a village Bargaon, but they connect their name with the bar or banyan tree, and revere it. At their weddings a branch of this tree is laid on the roof of the marriage-shed, and the wedding-cakes are cooked in a fire made of the wood of the banyan tree and served to all the relations of the sept on its leaves. At other times they will not pluck a leaf or a branch from a banyan tree or even go beneath its shade. The Kathotia sept is named after kathota, a bowl, but they revere the tiger. Bagheshwar Deo, the tiger-god, resides on a little platform in their verandas. They may not join in a tiger-beat nor sit up for a tiger over a kill. In the latter case they think that the tiger would not come and would be deprived of his food, and all the members of their family would get ill. If a tiger takes one of their cattle, they think there has been some neglect in their worship of him. They say that if one of them meets a tiger in the forest he will fold his hands and say, ‘Mahārāj, let me pass,’ and the tiger will then get out of his way. If a tiger is killed within the limits of his village a Kathotia Kol will throw away his earthen pots as in mourning for a relative, have his head shaved and feed a few men of his sept. The Katharia sept take their name from kathri, a mattress. A member of this sept must never have a mattress in his house nor wear clothes sewn in crosspieces as mattresses are sewn. The word kathri should never be mentioned before him as he thinks some great misfortune would thereby happen to his family, but this belief is falling into abeyance. The name of the Mudia or Mudrundia sept is said to mean shaven head, but they apparently revere the white kumhra or gourd, perhaps because it has some resemblance to a shaven head. They give a white gourd to a woman on the third day after she has borne a child, and her family then do not eat this vegetable for three years. At the expiration of the period the head of the family offers a chicken to Dulha Deo, frying it with the feathers left on the head, and eating the head and feet himself. Women may not join in this sacrifice. The Kumraya sept revere the brown kumhra or gourd. They grow this vegetable on the thatch of their house-roof, and from the time of planting it until the fruits have been plucked they do not touch it. The Bhuwar sept are named after bhu or bhumi, the earth. They must always sleep on the earth and not on cots. Other septs are Nathunia, a nose-ring; Karpatia, a kind of grass; and Binjhwār, from the tribe of that name. From Raigarh a separate group of septs is reported, the names of which further demonstrate the mixed nature of the tribe. Among these are Bandi, a slave; Kawar, Gond, Dhanuhār, Birjhia, all of which are the names of distinct tribes; Sonwāni, gold-water; Keriāri, or bridle; Khūnta, a peg; and Kapāt, a shutter.

10. Marriage customs

Marriage within the sept is prohibited, but violations of this rule are not infrequent. Outside the sept a man may marry any woman except the sisters of his mother or stepmother. Where, as in some localities, the septs have been forgotten, marriage is forbidden between those relatives to whom the sacramental cakes are distributed at a wedding. Among the Mundas, before a father sets out to seek a bride for his son, he invites three or four relatives, and at midnight taking a bottle of liquor pours a little over the household god as a libation and drinks the rest with them. They go to the girl’s village, and addressing her father say that they have come to hunt. He asks them in what jungle they wish to hunt, and they name the sarna or sacred grove in which the bones of his ancestors are buried. If the girl’s father is satisfied with the match, he then agrees to it. A bride-price of Rs. 10–8 is paid in the Central Provinces. Among the Hos of Chota Nāgpur so large a number of cattle was formerly demanded in exchange for a bride that many girls were never married. Afterwards it was reduced to ten head of cattle, and it was decided that one pair of bullocks, one cow and seven rupees should be equivalent to ten head, while for poor families Rs. 7 was to be the whole price.547 Among the Mundas of Raigarh the price is three or four bullocks, but poor men may give Rs. 12 or Rs. 18 in substitution. Here weddings may only be held in the three months of Aghan, Māgh and Phāgun,548 and preferably in Māgh. Their marriage ceremony is very simple, the bridegroom simply smearing vermilion on the bride’s forehead, after which water is poured over the heads of the pair. Two pots of liquor are placed beside them during the ceremony. It is also a good marriage if a girl of her own accord goes and lives in a man’s house and he shows his acceptance by dabbing vermilion on her. But her offspring are of inferior status to those of a regular marriage. The Kols of Jubbulpore and Mandla have adopted the regular Hindu ceremony.

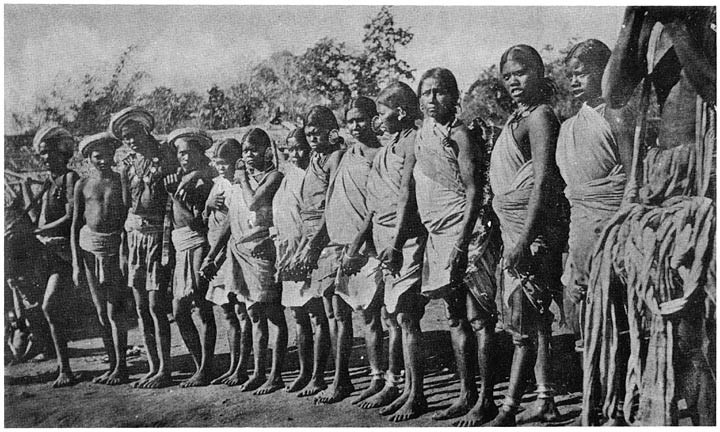

Group of Kol women

11. Divorce and widow-marriage

Divorce and widow-marriage are permitted. In Raigarh the widow is bound to marry her deceased husband’s younger brother, but not elsewhere. Among these Mundas, if divorce is effected by mutual consent, the husband must give his wife a pair of loin-cloths and provisions for six months. Polygamy is seldom practised, as women can earn their own living, and if a wife is superseded she will often run away home or set up in a house by herself. In Mandla a divorce can be obtained by either party, the person in fault having to pay a fee of Rs. 1–4 to the panchāyat; the woman then breaks her bangles and the divorce is complete.

12. Religion

At the head of the Munda pantheon, Sir H. Risley states,549 stands Sing-Bonga or the sun, a beneficent but ineffective deity who concerns himself but little with human affairs. But he may be invoked to avert sickness or calamity, and to this end sacrifices of white goats or white cocks are offered to him. Next to him comes Marang Buru, the mountain god, who resides on the summit of the most prominent hill in the neighbourhood. Animals are sacrificed to him here, and the heads left and appropriated by the priest. He controls the rainfall, and is appealed to in time of drought and when epidemic sickness is abroad. Other deities preside over rivers, tanks, wells and springs, and it is believed that when offended they cause people who bathe in the water to be attacked by leprosy and skin diseases. Even the low swampy rice-fields are haunted by separate spirits. Deswāli is the god of the village, and he lives with his wife in the Sarna or sacred grove, a patch of the primeval forest left intact to afford a refuge for the forest gods. Every village has its own Deswāli, who is held responsible for the crops, and receives an offering of a buffalo at the agricultural festival. The Jubbulpore Kols have entirely abandoned their tribal gods and now worship Hindu deities. Devi is their favourite goddess, and they carry her iron tridents about with them wherever they go. Twice in the year, when the baskets of wheat or Gardens of Adonis are sown in the name of Devi, she descends on some of her worshippers, and they become possessed and pierce their cheeks with the trident, sometimes leaving it in the face for hours, with one or two men standing beside to support it. When the trident is taken out a quid of betel is given to the wounded man, and the part is believed to heal up at once. These Kols also employ Brāhmans for their ceremonies. Before sowing their fields they say—