полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

10. The lunar year

Four seven-day weeks were within a day and a fraction of the lunar month, which was the nearest that could be got. The first method of measuring the year would be by twelve lunar months, which would bring it back nearly to the same period. But as the lunar month is 29 days 13 hours, twelve months would be 354 days 12 hours, or nearly eleven days less than the tropical solar year. Hence if the lunar year was retained the months would move back round the year by about eleven days annually. This is what actually happens in the Muhammadan calendar where the twelve lunar months have been retained and the Muharram and other festivals come earlier every year by about eleven days.

11. Intercalary months

In order to reconcile the lunar and solar years the Hindus hit upon an ingenious device. It was ordained that any month in which the sun did not enter a new sign of the zodiac would not count and would be followed by another month of the same name. Thus in the month of Chait the sun must enter the sign Mesha or Aries. If he does not enter it during the lunar month there will be an intercalary Chait, followed by the proper month of the same name during which the sun will enter Mesha.218 Such an intercalary month is called Adhika. An intercalary month, obtained by having two successive lunar months of the same name, occurs approximately once in three years, and by this means the reckoning by twelve lunar months is adjusted to the solar year. On the other hand, the sun very occasionally passes two Sankrānts or enters into two fresh signs during the lunar month. This is rendered possible by the fact that the time occupied by the sun in passing through different signs of the zodiac varies to some extent. It is said that the zodiac was divided into twelve equal signs of 30° each or 1° for each day, as at this period it was considered that the year was 360 days.219 Possibly in adjusting the signs to 365 odd days some alterations may have been made in their length, or errors discovered. At any rate, whatever may be the reason, the length of the sun’s periods in the signs, or of the solar months, varies from 31 days 14 hours to 29 days 8 hours. Three of the months are less than the lunar month, and hence it is possible that two Sankrānts or passages of the sun into a fresh sign may occasionally occur in the same lunar month. When this happens, following the same rule as before, the month to which the second Sankrānt properly belongs, that is the one following that in which two Sankrānts occur, is called a Kshaya or eliminated month and is omitted from the calendar. Intercalary months occur generally in the 3rd, 5th, 8th, 11th, 14th, 16th and 18th years of a cycle of nineteen years, or seven times in nineteen years. It is found that in each successive cycle only one or two months are changed, so that the same month remains intercalary for several cycles of nineteen years and then gives way generally to one of the months preceding and rarely to the following month. Suppressed months occur at intervals varying from 19 to 141 years, and in a year when a suppressed month occurs there must always be one intercalary month and not infrequently there are two.220

This method of adjusting the solar and lunar years, though clumsy, is so far scientific that the solar and lunar years are made to agree without any artificial intercalation of days. It has, however, the great disadvantages of the frequent intercalary month, and also of the fact that the lunar months begin on different dates in the English solar calendar, varying by nearly twenty days.

12. Superstitions about numbers

It seems not improbable that the unlucky character of the number thirteen may have arisen from its being the number of the intercalary month. Though the special superstition against sitting down thirteen to a meal is, no doubt, associated particularly with the Last Supper, the number is generally unlucky as a date and in other connections. And this is not only the case in Europe, but the Hindus, Persians and Pārsis also consider thirteen an unlucky number; and the Muhammadans account for a similar superstition by saying that Muhammad was ill for the first thirteen days of the month Safar. Twelve, as being the number of the months in the lunar and solar years, is an auspicious number; thirteen would be one extra, and as being the intercalary month would be here this year and missing next year. Hence it might be supposed that one of thirteen persons met together would be gone at their next meeting like the month. Similarly, the auspicious character of the number seven may be due to its being the total of the sun, moon and five planets, and of the days of the week named after them. And the number three may have been invested with mystic significance as representing the sun, moon and earth. In the Hindu Trinity Vishnu and Siva are the sun and moon, and Brahma, who created the earth, and has since remained quiescent, may have been the personified representative of the earth itself.

13. The Hindu months

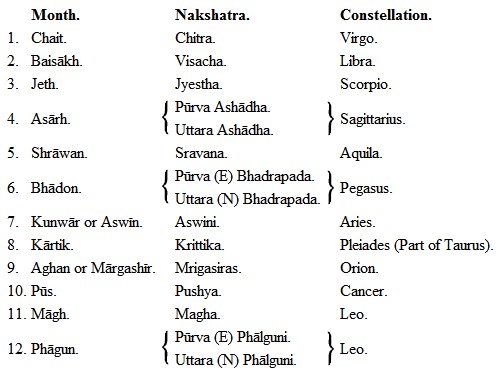

The names of the Hindu months were selected from among those of the nakshatras, every second or third being taken and the most important constellations apparently chosen. The following statement shows the current names for the months, the nakshatras from which they are derived, and the constellations they represent:

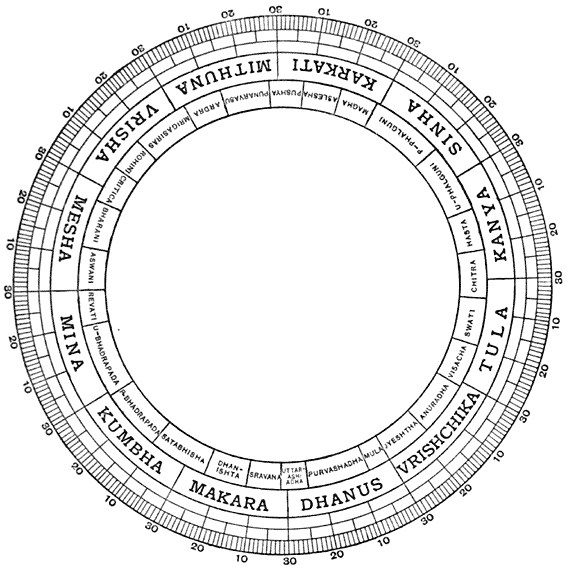

Thus if the Pleiades are reckoned as part of Taurus,221 eight zodiacal signs give their names to months as well as Orion, Pegasus and Aquila, while two months are included in Leo. It appears that in former times the year began with Pūs or December, as the month Mārgashīr was also called Aghan or Agrahana, or ‘That which went before,’ that is the month before the new year. But the renewal of vegetation in the spring has exercised a very powerful effect on the primitive mind, being marked by the Holi festival in India, corresponding to the Carnival in Europe. The vernal equinox was thus perhaps selected as the most important occasion and the best date for beginning the new year, which now commences in northern India with the new moon of Chait, immediately following the Holi festival, when the sun is in the sign of Mesha or Aries. At first the months appear to have travelled round the year, but subsequently they were fixed by ordaining that the month of Chait should begin with the new moon during the course of which the sun entered the sign Aries.222 The constellation Chitra, from which the sign is named, is nearly opposite to this in the zodiac, as shown by the above figure.223

Fig. 3.—The Hindu Ecliptic showing the relative position of Zodiacal Signs and Nakshatras.

Consequently, the full moon, being nearly opposite the sun on the ecliptic, would be in the sign Chitra or near it. In southern India the months begin with the full moon, but in northern India with the new moon; it seems possible that the months were called after the nakshatra, of the full moon to distinguish them from the solar months which would be called after the sign of the zodiac in which the sun was. But no authoritative explanation seems to be available. Similarly, the nakshatras after which the other months are named, fall nearly opposite to them at the new moon, while the full moon would be in or near them.

14. The solar nakshatras

The periods during which the sun passes through each nakshatra are also recorded, and they are of course constant in date like the solar months. As there are twenty-seven nakshatras, the average time spent by the sun in each is about 13½ days. These periods are well known to the people as they have the advantage of not varying in date like the lunar months, while over most of India the solar months are not used. The commencement of the various agricultural operations is dated by the solar nakshatras, and there are several proverbs about them in connection with the crops. The following are some examples: “If it does not rain in Pushya and Punarvasu Nakshatras the children of Nimār will go without food.” ‘Rain in Magha Nakshatra (end of August) is like food given by a mother,’ because it is so beneficial. “If there is no wind in Mrigasiras (beginning of June), and no heat in Rohini (end of May), sell your plough-cattle and go and look for work.” ‘If it rains during Uttara (end of September) dogs will turn up their noses at grain,’ because the harvest will be so abundant. “If it rains during Aslesha (first half of August) the wheat-stalks will be as stout as drum-sticks” (because the land will be well ploughed). ‘If rain falls in Chitra or Swāti Nakshatras (October) there won’t be enough cotton for lamp-wicks.’

15. Lunar fortnights and days

The lunar month was divided into two fortnights called paksha or wing. The period of the waxing moon was known as sukla or sudi paksha, that is the light fortnight, and that of the waning moon as krishna or budi paksha, that is the dark fortnight.

Each lunar month was also divided into thirty equal periods, called tithis or lunar days. Since there are less than thirty days in the lunar month, a tithi does not correspond to an ordinary day, but begins and ends at odd hours of the day. Nevertheless the tithis are printed in all almanacs, and are used for the calculation of auspicious moments.224

16. Divisions of the day

The day is divided for ordinary purposes of measuring time into eight pahars or watches, four of the day and four of the night; and into sixty gharis or periods of twenty-four minutes each. The pahars, however, are not of equal length. At the equinox the first and fourth pahar of the day and night each contain eight gharis, and the two middle ones seven gharis. In summer the first and fourth pahars of the day contain nine gharis each, and the two middle ones eight each, while the first and fourth pahars of the night contain seven and the two middle ones six each. Thus in summer the four day pahars contain 13 hours 36 minutes and the night ones 10 hours 24 minutes. And in winter the exact opposite is the case, the night pahars being lengthened and the day ones shortened in precisely the same manner. No more unsatisfactory measure of time could well be devised. The termination of the second watch or do pahar always corresponds with midday and midnight respectively.

The apparatus with which the hours were measured and announced consisted of a shallow metal pan, named from its office, ghariāl, and suspended so as to be easily struck with a wooden mallet by the ghariāli. He measured the passing of a ghari by an empty thin brass cup or katori, perforated at the bottom, and placed on the surface of a large vessel filled with water, where nothing could disturb it; the water came through the small hole in the bottom of the cup and filled it, causing it to sink in the period of one ghari. At the expiration of each ghari the ghariāl struck its number from one to nine with a mallet on a brass plate, and at the end of each pahar he struck a gujar or eight strokes to announce the fact, followed by one to four hollow-sounding strokes to indicate the number of the pahar. This custom is still preserved in the method by which the police-guards of the public offices announce the hours on a gong and subsequently strike four, eight and twelve strokes to proclaim these hours of the day and night by our clock. Only rich men could afford to maintain a ghariāl, as four persons were required to attend to it during the day and four at night.225

17. The Joshi’s calculations

The Joshi calculates auspicious226 seasons by a consideration of the sun’s zodiacal sign, the moon’s nakshatra or daily mansion, and other rules. From the monthly zodiacal signs and daily nakshatras in which children are born, as recorded in their horoscopes, he calculates whether their marriage will be auspicious. Thus the zodiacal signs are supposed to be divided among the four castes, Pisces, Cancer and Scorpio belonging to the Brāhman; Aries, Leo and Sagittarius to the Kshatriya; Taurus, Virgo and Capricorn to the Vaishya; and Gemini, Libra and Aquarius to the Sūdra. If the boy and girl were born under any of the three signs of the same caste it is a happy conjunction. If the boy’s sign was of a caste superior to the girl’s, it is suitable, but if the girl’s sign is of a superior caste to the boy’s it is an omen that she will rule the household; and though the marriage may take place, certain ceremonies should be performed to obviate this effect. There is also a division of the zodiacal signs according to their nature. Thus Virgo, Libra, Gemini, Aquarius and half of Sagittarius are considered to be of the nature of man, or formed by him; Aries, Taurus, half of Sagittarius and half of Capricorn are of the nature of animals; Cancer, Pisces and half of Capricorn are of a watery nature; Leo is of the desert or wild nature; and Scorpio is of the nature of insects. If the boy and girl were both born under signs of the same nature their marriage will be auspicious, but if they were born under signs of different natures, they will share only half the blessings and comforts of the marriage state, and may be visited by strife, enmity, misery or distress. As Leo and Scorpio are looked upon as being enemies, evil consequences are much dreaded from the marriage of a couple born under these signs. There are also numerous rules regarding the nakshatras or mansions of the moon and days of the week under which the boy and girl were born, but these need not be reproduced. If on the day of the wedding the sun or any of the planets passes from one zodiacal sign to another, the wedding must be delayed for a certain number of gharis or periods of twenty-four minutes, the number varying for each planet. The hours of the day are severally appointed to the seven planets and the twelve zodiacal signs, and the period of ascendancy of a sign is known as lagan; this name is also given to the paper specifying the day and hour which have been calculated as auspicious for the wedding. It is stated that no weddings should be celebrated during the period of occultation of the planets Jupiter and Venus, nor on the day before new moon, nor the Sankrānt or day on which the sun passes from one zodiacal sign to another, nor in the Singhast year, when the planet Jupiter is in the constellation Leo. This takes place once in twelve years. Marriages are usually prohibited during the four months of the rainy season, and sometimes also in Pūs, Jeth or other months.

18. Personal names

The Joshi names children according to the moon’s daily nakshatra under which they were born, each nakshatra having a letter or certain syllables allotted to it with which the name must begin. Thus Magha has the syllables Ma, Mi, Mu and Me, with which the name should begin, as Mansāram, Mithu Lāl, Mukund Singh, Meghnāth; Purwa Phālguni has Mo and Te, as Moji Lāl and Tegi Lāl; Punarvasu has Ke, Ko, Ha and Hi, as Kesho Rao, Koshal Prasād, Hardyāl and Hīra Lāl, and so on. The primitive idea connecting a name with the thing or person to which it belongs is that the name is actually a concrete part of the person or object, containing part of his life, just as the hair, nails and all the body are believed to contain part of the life, which is not at first localised in any part of the body nor conceived of as separate from it. The primitive mind could conceive no abstract idea, that is nothing that could not be seen or heard, and it could not think of a name as an abstract appellation. The name was thought of as part of that to which it was applied. Thus, if one knew a man’s name, it was thought that one could use it to injure him, just as if one had a piece of his hair or nails he could be injured through them because they all contained part of his life; and if a part of the life was injured or destroyed the remainder would also suffer injury, just as the whole body might perish if a limb was cut off. For this reason savages often conceal their real names, so as to prevent an enemy from obtaining power to injure them through its knowledge. By a development of the same belief it was thought that the names of gods and saints contained part of the divine life and potency of the god or saint to whom they were applied. And even separated from the original owner the name retained that virtue which it had acquired in association; hence the power assigned to the names of gods and superhuman beings when used in spells and incantations. Similarly, if the name of a god or saint was given to a child it was thought that some part of the nature and virtue of the god might be conferred on the child. Thus Hindu children are most commonly named after gods and goddesses under the influence of this idea; and though the belief may now have decayed the practice continues. Similarly the common Muhammadan names are epithets of Allah or god or of the Prophet and his relations. Jewish children are named after the Jewish patriarchs. In European countries the most common male names are those of the Apostles, as John, Peter, James, Paul, Simon, Andrew and Thomas; and the names of the Evangelists were, until recently, also given. The most common girl’s name in several European countries is Mary, and a generation or two ago other Biblical names, as Sarah, Hannah, Ruth, Rachel, and so on, were very usually given to girls. In England the names next in favour for boys and girls are those of kings and queens, and the same idea perhaps originally underlay the application of these names. The following are some of the best-known Hindu names, taken from those of gods:—

Names of Vishnu.

Nārāyan. Probably ‘The abode of mortals,’ or else ‘He who dwelt on the waters (before creation)’; now applied to the sun.

Wāman. The dwarf, one of Vishnu’s incarnations.

Janārdan. Said to mean protector of the people.

Narsingh. The man-lion, one of Vishnu’s incarnations.

Hari. Yellow or gold-colour or green. Perhaps applied to the sun.

Parashrām. From Parasurāma or Rāma with the axe, one of the incarnations of Vishnu.

Gadadhar. Wielder of the club or gada.

Jagannāth. Lord of the world.

Dīnkar. The sun, or he who makes the days (dīn karna).

Bhagwān. The fortunate or illustrious.

Anant. The infinite or eternal.

Madhosūdan. Destroyer of the demon Madho (Madho means honey or wine).

Pāndurang. Yellow-coloured.

Names of Rāma, or Vishnu’s Great Incarnation as King Rāma of Ayodhia.

Rāmchandra, the moon of Rāma, and Rāmbaksh, the gift of Rāma, are the commonest Hindu male names.

Atmārām. Soul of Rāma.

Sitārām. Rāma and Sita his wife.

Rāmcharan. The footprint of Rāma.

Sakhārām. The friend of Rāma.

Sewārām. Servant of Rāma.

Names of Krishna.

Krishna and its diminutive Kishen are very common names.

Kanhaiya. A synonym for Krishna.

Dāmodar. Because his mother tied him with a rope to a large tree to keep him quiet and he pulled up the tree, roots and all.

Bālkishen. The boy Krishna.

Ghansiām. The dark-coloured or black one (like dark clouds); probably referring to the belief that Krishna belonged to the non-Aryan races.

Madan Mohan. The enchanter of love.

Manohar. The heart-stealer.

Yeshwant. The glorious.

Kesho. Having long, fine hair. A name of Krishna. Also the destroyer of the demon Keshi, who was covered with hair. It would appear that the epithet was first applied to Krishna himself and afterwards to a demon whom he was supposed to have destroyed.

Balwant. Strong. An epithet of Krishna, used in conjunction with other names.

Mādhava. Honey-sweet or belonging to the spring, vernal.

Girdhāri. He who held up the mountain. Krishna held up the mountain Govardhan, balancing the peak on his finger to protect the people from the destructive rains sent by Indra.

Shiāmsundar. The dark and beautiful one.

Nandkishore, Nandkumār. Child of Nand the cowherd, Krishna’s foster-father.

Names of Siva.

Sadāsheo. Siva the everlasting.

Mahādeo. The great god.

Trimbak. The three-eyed one (?).

Gangādhar. The holder of the Ganges, because it flows from Siva’s hair.

Kāshināth. The lord of Benāres.

Kedārnāth. The lord of cedars (referring to the pine-forests of the Himālayas).

Nīlkanth. The blue-jay sacred to Siva. Name of Siva because his throat is bluish-black either from swallowing poison at the time of the churning of the ocean or from drinking large quantities of bhāng.

Shankar. He who gives happiness.

Vishwanāth. Lord of the universe.

Sheo Prasād. Gift of Siva.

Names of Ganpati or Ganesh.

Ganpati is itself a very common name.

Vidhyādhar. The lord of learning.

Vināyak. The remover of difficulties.

Ganesh Prasād. Gift of Ganesh. A child born on the fourth day of any month will often be given this name, as Ganesh was born on the 4th Bhādon (August).

Names of Hanumān.

Hanumān itself is a very common name.

Māroti, son of Mārut the god of the wind.

Mahāvīra or Mahābīr. The strong one.

Other common sacred names are: Amrit, the divine nectar, and Moreshwar, lord of the peacock, perhaps an epithet of the god Kartikeya. Men are also often named after jewels, as: Hīra Lāl, diamond; Panna Lāl, emerald; Ratan Lāl, a jewel; Kundan Lāl, fine gold. A child born on the day of full moon may be called Pūran Chand, which means full moon. There are of course many other male names, but those here given are the commonest. Children are also frequently named after the day or month in which they were born.

19. Terminations of names

Common terminations of male names are: Charan, footprint; Dās, slave; Prasād, food offered to a god; Lāl, dear; Datta, gift, commonly used by Maithil Brāhmans; Dīn or Baksh, which also means gift; Nāth, lord of; and Dulāre, dear to. These are combined with the names of gods, as: Kālicharan, footprint of Kāli; Rām Prasād or Kishen Prasād, an offering to Rāma or Krishna; Bishen Lāl, dear to Vishnu; Ganesh Datta, a gift from Ganesh; Ganga Dīn, a gift from the Ganges; Sheo Dulāre, dear to Siva; Vishwanāth, lord of the universe. Boys are sometimes given the names of goddesses with such terminations, as Lachmi or Jānki Prasād, an offering to these goddesses. A child born on the 8th of light Chait (April) will be called Durga Prasād, as this day is sacred to the goddess Durga or Devi.

20. Women’s names

Women are also frequently named after goddesses, as: Pārvati, the consort of Siva; Sīta, the wife of Rāma; Jānki, apparently another name for Sīta; Lakshmi, the consort of Vishnu, and the goddess of wealth; Sāraswati, the goddess of wisdom; Rādha, the beloved of Krishna; Dasoda, the foster-mother of Krishna; Dewāki, who is supposed to have been the real mother of Krishna; Durga, another name for Siva’s consort; Devi, the same as Durga and the earth-goddess; Rukhmini, the bright or shining one, a consort of Vishnu; and Tulsi, the basil-plant, sacred to Vishnu.

Women are also named after the sacred rivers, as: Ganga, Jamni or Yamuni (Jumna); Gomti, the river on which Lucknow stands; Godha or Gautam, after the Godāvari river; and Bhāgirathi, another name for the Ganges. The river Nerbudda is commonly found as a man’s name, especially in places situated on its banks. Other names of women are: Sona, gold; Puna, born at the full moon; Manohra, enchanting; Kamala, the lotus; Indumati, a moonlight night; Sumati, well-minded; Sushila, well-intentioned; Srimati, wealthy; Amrita, nectar; Phulwa, a flower; Imlia, the tamarind; Malta, jasmine; and so on.

If a girl is born after four sons she will be called Pancho or fifth, and one born in the unlucky Mul Nakshatra is called Mulia. When a girl is married and goes to her husband’s house her name is always changed there. If two girls have been married into the household, they may be called Bari Bohu and Choti Bohu, or the elder and younger daughters-in-law; or a girl may be called after the place from which she comes, as Jabalpurwāli, Raipurwāli, and so on.