полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

8. Burial

The Jogis are buried sitting cross-legged with the face to the north in a tomb which has a recess like those of Muhammadans. A gourd full of milk and some bread in a wallet, a crutch and one or two earthen vessels are placed in the grave for the sustenance of the soul. Salt is put on the body and a ball of wheat-flour is laid on the breast of the corpse and then deposited on the top of the grave.

9. Festivals

The Jogis worship Siva, and their principal festival is the Shivrātri, when they stay awake all night and sing songs in honour of Gorakhnāth, the founder of their order. On the Nāg-Panchmi day they venerate the cobra and they take about snakes and exhibit them.

10. Caste subdivisions

A large proportion of the Jogis have now developed into a caste, and these marry and have families. They are divided into subcastes according to the different professions they have adopted. Thus the Barwa or Gārpagāri Jogis ward off hailstorms from the standing crops; the Manihāri are pedlars and travel about to bazārs selling various small articles; the Rītha Bikanāth prepare and sell soap-nut for washing clothes; the Patbina make hempen thread and gunny-bags for carrying grain on bullocks; and the Ladaimār hunt jackals and sell and eat their flesh. These Jogis rank as a low Hindu caste of the menial group. No good Hindu caste will take food or water from them, while they will accept cooked food from members of any caste of respectable position, as Kurmis, Kunbis or Mālis. A person belonging to any such caste can also be admitted into the Jogi community. Their social customs resemble those of the cultivating castes of the locality. They permit widow-marriage and divorce and employ Brāhmans for their ceremonies, with the exception of the Kanphatas, who have priests of their own order.

11. Begging

Begging is the traditional occupation of the Jogis, but they have now adopted many others. The Kanphatas beg and sell a woollen string amulet (ganda), which is put round the necks of children to protect them from the evil eye. They beg only from Hindus and use the cry ‘Alakh,’ ‘The invisible one.’206 The Nandia Jogis lead about with them a deformed ox, an animal with five legs or some other malformation. He is decorated with ochre-coloured rags and cowrie shells. They call him Nandi or the bull on which Mahādeo rides, and receive gifts of grain from pious Hindus, half of which they put into their wallet and give the other half to the animal. They usually carry on a more profitable business than other classes of beggars. The ox is trained to give a blessing to the benevolent by shaking its head and raising its leg when its master receives a gift.207 Some of the Jogis of this class carry about with them a brush of peacock’s feathers which they wave over the heads of children afflicted with the evil eye or of sick persons, muttering texts. This performance is known as jhārna (sweeping), and is the commonest method of casting out evil spirits.

12. Other occupations

Many Jogis have also adopted secular occupations, as has already been seen. Of these the principal are the Manihāri Jogis or pedlars, who retail small hand-mirrors, spangles, dyeing-powders, coral beads and imitation jewellery, pens, pencils, and other small articles of stationery. They also bring pearls and coral from Bombay and sell them in the villages. The Gārpagāris, who protect the crops from hailstorms, have now become a distinct caste and are the subject of a separate article. Others make a living by juggling and conjuring, and in Saugor some Jogis perform the three-card trick in the village markets, employing a confederate who advises customers to pick out the wrong card. They also play the English game of Sandown, which is known as ‘Animur,’ from the practice of calling out ‘Any more’ as a warning to backers to place their money on the board before beginning to turn the fish.

13. Swindling practices

These people also deal in ornaments of base metal and practise other swindles. One of their tricks is to drop a ring or ornament of counterfeit gold on the road. Then they watch until a stranger picks it up and one of them goes up to him and says, “I saw you pick up that gold ring, it belongs to so-and-so, but if you will make it worth my while I will say nothing about it.” The finder is thus often deluded into giving him some hush-money and the Jogis decamp with this, having incurred no risk in connection with the spurious metal. They also pretend to be able to convert silver and other metals into gold. They ingratiate themselves with the women, sometimes of a number of households in one village or town, giving at first small quantities of gold in exchange for silver, and binding them to secrecy. Then each is told to give them all the ornaments which she desires to be converted on the same night, and having collected as much as possible from their dupes the Jogis make off before morning. A very favourite device some years back was to personate some missing member of a family who had gone on a pilgrimage. Up to within a comparatively recent period a large proportion of the pilgrims who set out annually from all over India to visit the famous shrines at Benāres, Jagannāth and other places perished by the way from privation or disease, or were robbed and murdered, and never heard of again by their families. Many households in every town and village were thus in the position of having an absent member of whose fate they were uncertain. Taking advantage of this, and having obtained all the information he could pick up among the neighbours, the Jogi would suddenly appear in the character of the returned wanderer, and was often successful in keeping up the imposture for years.208

14. Proverbs about Jogis

The Jogi is a familiar figure in the life of the people and there are various sayings about him:209 Jogi Jogi laren, khopron ka dām, or ‘When Jogis fight skulls are smashed,’ that is, the skulls which some of them use as begging-cups, not their own skulls, and with the implication that they have nothing else to break; Jogi jugat jāni nahīn, kapre range, to kya hua, ‘If the Jogi does not know his magic, what is the use of his dyeing his clothes?’ Jogi ka larka khelega, to sānp se, or, ‘If a snake-charmer’s son plays, he plays with a snake.’

Joshi

1. The village priest and astrologer

Joshi, Jyotishi, Bhadri, Parsai.—The caste of village priests and astrologers. They numbered about 6000 persons in 1911, being distributed over all Districts. The Joshis are nearly all Brāhmans, but have now developed into a separate caste and marry among themselves. Their social customs resemble those of Brāhmans, and need not be described in detail. The Joshi officiates at weddings in the village, selects auspicious names for children according to the nakshatra or constellation of the moon under which they were born, and points out the auspicious time or mahūrat for all such ceremonies and for the commencement of agricultural operations. He is also sometimes in charge of the village temples. He is supported by the contributions from the villagers, and often has a plot of land rent-free from the proprietor. The social position of the Joshis is not very good, and, though Brāhmans, they are considered to rank somewhat below the cultivating castes, the Kurmis and Kunbis, by whose patronage they are supported.210

The Bhadris are a class of Joshis who wander about and live by begging, telling fortunes and giving omens. They avert the evil influences of the planet Saturn and accept the gifts offered to this end, which are always black, as black blankets, charcoal, tilli or sesamum oil, the urad pulse,211 and iron. People born on Saturday or being otherwise connected with the planet are especially subject to his malign influence. The Joshi ascertains who these unfortunate persons are from their horoscopes, and neutralises the evil influence of the planet by the acceptance of the gifts already mentioned, while he sometimes also receives a buffalo or a cow. He computes by astrological calculations the depth at which water will be found when a cultivator wishes to dig a well. He also practises palmistry, classifying the whorls of the fingers into two patterns, called the Shank or conch-shell and Chakra or discus of Vishnu. The Shank is considered to be unfortunate and the Chakra fortunate. The lines on the balls of the toes and on the forehead are similarly classified. When anything has been lost or stolen the Joshi can tell from the daily nakshatra or mansion of the moon in which the loss or theft occurred whether the property has gone to the north, south, east or west, and within what interval it is likely to be found. The people have not nowadays much faith in his prophetic powers, and they say, “If clouds come on Friday, and the sky is black on Saturday, then the Joshi foretells that it will rain on Sunday.” The Joshi’s calculations are all based on the rāshis or signs of the zodiac through which the sun passes during the year, and the nakshatras or those which mark the monthly revolutions of the moon. These are given in all Hindu almanacs, and most Joshis simply work from the almanac, being quite ignorant of astronomy. Since the measurement of the sun’s apparent path on the ecliptic, and the moon’s orbit mapped out by the constellations are of some interest, and govern the arrangement of the Hindu calendar, it has been thought desirable to give some account of them. And in order to make this intelligible it is desirable first to recapitulate some elementary facts of astronomy.

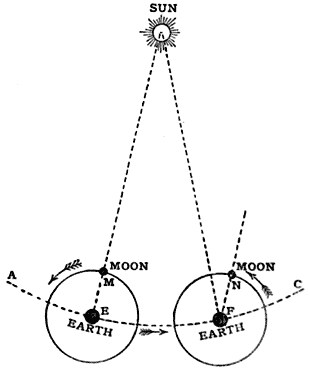

2. The apparent path of the sun. The ecliptic or zodiac

The universe may be conceived for the purpose of understanding the sun’s path among the stars as if it were a huge ball, of which looking from the earth’s surface we see part of the inside with the stars marked on it, as on the inside of a dome. This imaginary inside of a ball is called the celestial sphere, and the ancients believed that it actually existed, and also, in order to account for the varying distances of the stars, supposed that there were several of them, one inside the other, and each with a number of stars fixed to it. The sun and earth may be conceived as smaller solid balls suspended inside this large one. Then looking from the surface of the earth we see the sun outlined against the inner surface of the imaginary celestial sphere. And as the earth travels round the sun in its orbit, the appearance to us is that the sun moves over the surface of the celestial sphere. The following figure will make this clear.212

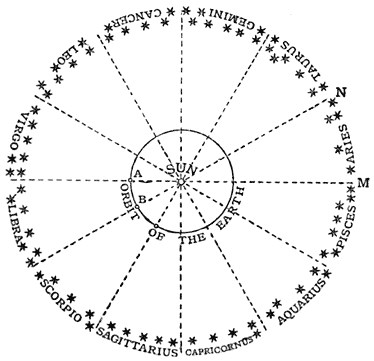

Fig. 1.—The Orbit of the Earth and the Zodiac.

Thus when the earth is at A in its orbit the sun will appear to be at M, and as the earth travels from A to B the sun will appear to move from M to N on the line of the ecliptic. It will be seen that as the earth in a year makes a complete circuit round the sun, the sun will appear to have made a complete circuit among the stars, and have come back to its original position. This apparent movement is annual, and has nothing to do with the sun’s apparent diurnal course over the sky, which is caused by the earth’s daily rotation on its axis. The sun’s annual path among the stars naturally cannot be observed during the day. Professor Newcomb says: “But the fact of the motion will be made very clear if, day after day, we watch some particular fixed star in the west. We shall find that it sets earlier and earlier every day; in other words, it is getting continually nearer and nearer the sun. More exactly, since the real direction of the star is unchanged, the sun seems to be approaching the star.

“If we could see the stars in the daytime all round the sun, the case would be yet clearer. We should see that if the sun and a star were together in the morning, the sun would, during the day, gradually work past the star in an easterly direction. Between the rising and setting it would move nearly its own diameter, relative to the star. Next morning we should see that it had got quite away from the star, being nearly two diameters distant from it. This motion would continue month after month. At the end of the year the sun would have made a complete circuit relative to the star, and we should see the two once more together. This apparent motion of the sun in one year round the celestial sphere was noticed by the ancients, who took much trouble to map it out. They imagined a line passing round the celestial sphere, which the sun always followed in its annual course, and which was called the ecliptic. They noticed that the planets followed nearly the same course as the sun among the stars. A belt extending on each side of the ecliptic, and broad enough to contain all the known planets, as well as the sun, was called the zodiac. It was divided into twelve signs, each marked by a constellation. The sun went through each sign in a month, and through all twelve signs in a year. Thus arose the familiar signs of the zodiac, which bore the same names as the constellations among which they are situated. This is not the case at present, owing to the precession of the equinoxes.” It was by observing the paths of the sun and moon round the celestial sphere along the zodiac that the ancients came to be able to measure the solar and lunar months and years.

3. Inclination of the ecliptic to the equator

As is well known, the celestial sphere is imagined to be spanned by an imaginary line called the celestial equator, which is in the same plane as the earth’s equator, and as it were, a vast concentric circle. The points in the celestial sphere opposite the north and south terrestrial poles are called the north and south celestial poles, and the celestial equator is midway between these. Owing to the special form of the earth the north celestial pole is visible to us in the northern hemisphere, and marked very nearly by the pole-star, its height above the horizon being equal to the latitude of the place where the observer stands. Owing to the daily rotation of the earth the whole celestial sphere seems to revolve daily on the axis of the north and south celestial poles, carrying the sun, moon and stars with it. To this the apparent daily course of the sun and moon is due. Their course seems to us oblique, as we are north of the equator.

If the earth’s axis were set vertically to the plane of its orbit round the sun, then it would follow that the plane of the equator would pass through the centre of the sun, and that the line drawn by the sun in its apparent revolution against the background of the celestial sphere would be in the same plane. That is, the sun would seem to move round a circle in the heavens in the same plane as the earth’s equator, or round the celestial equator. But the earth’s axis is inclined at 23½° to the plane of its orbit, and therefore the apparent path traced by the sun in the celestial sphere, which is the same path as the earth would really follow to an observer on the surface of the sun, is inclined at 23½° to the celestial equator. This is the ecliptic, and is really the line of the plane of the earth’s orbit extended to cut the celestial sphere.

4. The orbits of the moon and planets

All the planets move round the sun in orbits whose planes are slightly inclined to that of the earth, the plane of Mercury having the greatest inclination of 6°. The plane of the moon’s orbit round the earth is also inclined at 5° 9′ to the ecliptic. The orbits of the moon and all the planets must necessarily intersect the plane of the earth’s orbit on the ecliptic at two points, and these are called the nodes of the moon and each planet respectively. In consequence of the inclination being so slight, though the course of the moon and planets is not actually on the ecliptic, they are all so close to it that they are included in the belt of the zodiac. Thus the moon and all the planets follow almost the same apparent course on the zodiac or belt round the ecliptic in the changes of position resulting from their own and the earth’s orbital movements with reference to what are called the fixed stars.

5. The signs of the zodiac

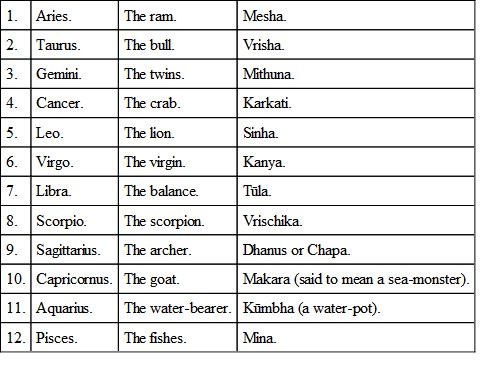

As the sun completes his circuit of the ecliptic or zodiac in the course of a year, it followed that if his course could be measured and divided into periods, these periods would form divisions of time for the year. This was what the ancients did, and it is probable that the measurement and division of time was the primary object of the science of astronomy, as apart from the natural curiosity to ascertain the movements of the sun, moon and planets, when they were looked upon as divine beings controlling the world. They divided the zodiac or the path of the sun into twelve parts, and gave to each part the name of the principal constellation situated on, or adjacent to, that section of the line of the ecliptic. When they had done this and observed the dates of the sun’s entry into each sign or rāshi, as it is called in Hindi, they had divided the year into twelve solar months. The following are the Hindu names and meanings of the signs of the zodiac:

The signs of the zodiac were nearly the same among the Greeks, Egyptians, Persians, Babylonians and Indians. They are supposed to have originated in Chaldea or Babylonia, and the fact that the constellations are indicated by nearly the same symbols renders their common origin probable. It seems likely that the existing Hindu zodiac may have been adopted from the Greeks.

6. The Sankrānts

The solar year begins with the entrance of the sun into Mesha or Aries.213 The day on which the sun passes into a new sign is called Sankrānt, and is to some extent observed as a holy day. But the Til Sankrānt or entry of the sun into Makara or Capricorn, which falls about the 15th January, is a special festival, because it marks approximately the commencement of the sun’s northern progress and the lengthening of the days, as Christmas roughly does with us. On this day every Hindu who is able bathes in a sacred river at the hour indicated by the Joshis of the sun’s entrance into the sign. Presents of til or sesamum are given to the Joshi, owing to which the day is called Til Sankrānt. People also sometimes give presents to each other.

7. The nakshatras or constellations of the moon’s path

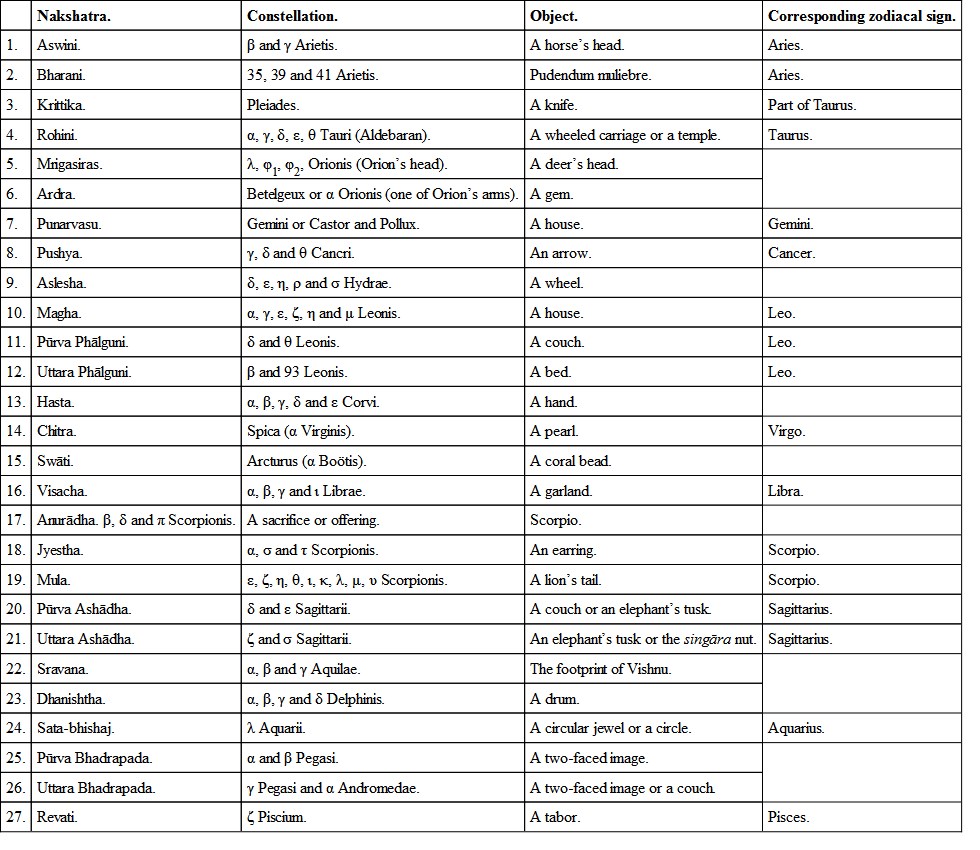

The Sankrānts do not mark the commencement of the Hindu months, which are still lunar and are adjusted to the solar year by intercalation. It is probable that long before they were able to measure the sun’s progress along the ecliptic the ancients had observed that of the moon, which it was much easier to do, as she is seen among the stars at night. Similarly there is little reason to doubt that the first division of time was the lunar month, which can be remarked by every one. Ancient astronomers measured the progress of the moon’s path along the ecliptic and divided it into twenty-seven sections, each of which represented roughly a day’s march. Each section was distinguished by a group of stars either on the ecliptic or so near it, either in the northern or southern hemisphere, as to be occultated by the moon or capable of being in conjunction with it or the planets. These constellations are called nakshatras. Naturally, some of these constellations are the same as those subsequently chosen to mark the sun’s path or the signs of the zodiac. In some cases a zodiacal constellation is divided into two nakshatras. Like the signs, the nakshatras were held to represent animals or natural objects. The following is a list of them with their corresponding stars, and the object which each was supposed to represent:214

8. The revolution of the moon

All the zodiacal constellations are thus included in the nakshatras except Capricorn, for which Aquila and Delphinis are substituted. These, as well as Hydra, are a considerable distance from the ecliptic, but may perhaps be nearer the moon’s path, which, as already seen, slightly diverges from it. But this point has not been ascertained by me. The moon completes the circuit of the heavens in its orbit round the earth in a little less than a lunar month or 27 days 8 hours. As twenty-seven nakshatras were demarcated, it seems clear that a nakshatra was meant to represent the distance travelled by the moon in a day. Subsequently a twenty-eighth small nakshatra was formed called Abhijit, out of Uttarāshādha and Sravana, and this may have been meant to represent the fractional part of the day. The days of the lunar month have each, as a matter of fact, a nakshatra allotted to them, which is recorded in all Hindu almanacs, and enters largely into the Joshi’s astrological calculations. It may have been the case that prior to the naming of the days of the week, the days of the lunar month were distinguished by the names of their nakshatras, but this could only have been among the learned. For though there was a nakshatra for every day of the moon’s path round the ecliptic, the same days in successive months could not have the same nakshatras on account of what is called the synodical revolution of the moon. The light of the moon comes from the sun, and we see only that part of it which is illuminated by the sun. When the moon is between the earth and the sun, the light hemisphere is invisible to us, and there is no moon. When the moon is on the opposite side of the earth to the sun we see the whole of the illuminated hemisphere, and it is full moon. Thus in the time between one new moon and the next, the moon must proceed from its position between the earth and the sun to the same position again, and to do this it has to go somewhat more than once round the ecliptic, as is shown by the following figure.215

Fig. 2.—Revolution of the Moon round the Earth.

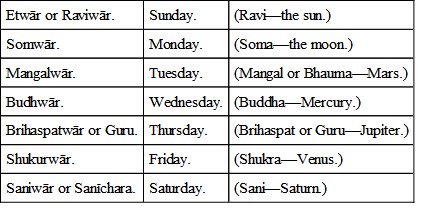

9. The days of the week

As during the moon’s circuit of the earth, the earth is also travelling on its orbit, the moon will not be between the earth and the sun again on completion of its orbit, but will have to traverse the further arc shown in the figure to come between the earth and the sun. When the moon has completed the circle of the ecliptic from the position ME, its position relative to the earth has become as NF and it has not yet come between the earth and the sun. Hence while the moon completes the circuit of the ecliptic216 in 27 days 8 hours, the time from one new moon to another is 29 days 13 hours. Hence the nakshatras will not fall on the same days in successive lunar months, and would not be suitable as names for the days. It seems that, recognising this, the ancient astronomers had to find other names. They had the lunar fortnights of 14 or 15 days from new to full and full to new moon. Hence apparently they hit on the plan of dividing these into half and regulating the influence which the sun, moon and planets were believed to exercise over events in the world by allotting one day to each of them. They knew of five planets besides the sun and moon, and by giving a day to each of them the seven-day week was formed. The term planet signifies a wanderer, and it thus perhaps seemed suitable that they should give their names to the days which would revolve endlessly in a cycle, as they themselves did in the heavens. The names of the days are:

The termination vāra means a day. The weekdays were similarly named in Rome and other countries speaking Aryan languages, and they are readily recognised in French. In English three days are named after the sun, moon and Saturn, but four, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, are called after Scandinavian deities, the last three being Woden or Odin, Thor and Freya. I do not know whether these were identified with the planets. It is supposed that the Hindus obtained the seven-day week from the Greeks.217