полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

3. Admission of outsiders

They will admit Brāhmans, Rājpūts and Halbas into the community. If a man of any of these castes has a child by a Telenga woman, this child will be considered to belong to the same group of the Jhādi Telengas as its mother. If a man of lower caste, such as Rāwat, Dhākar, Jangam, Kumhār or Kalār has such a child it will be admitted into the next lower group than that to which the mother belonged. Thus the child of a Purāit woman by one of these castes will become a Surāit. A Telenga woman having a child by a Gond, Sunār, Lohār or Mehra man is put out of caste.

4. Marriage

A girl cannot be properly married unless the ceremony is performed before she arrives at puberty. After this she can only be married by an abridged rite, which consists of rubbing her with oil and turmeric, investing her with glass bangles and a new cloth, and giving a feast to the caste. In such a case the bridegroom first goes through a sham marriage with the branch of a mahua tree. The boy’s father looks out for a girl, and the most suitable match is considered to be his sister’s daughter. Before giving away his daughter he must ask his wife’s brother and his own sister whether they want her for one of their sons. When setting out to make a proposal they take the omens from a bird called Usi. The best omen is to hear this bird’s call on both sides of them as they go into the jungle. When asking for the girl the envoys say to her father, ‘You have got rice and pulse; give them to us for our friend’s son.’ The wedding should be held on a Monday or Thursday, and the bridegroom should arrive at the bride’s village on a Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday or Friday. The sacred post in the centre of the marriage-shed must be of the mahua191 tree, which is no doubt held sacred by these people, as by the Gonds, because spirituous liquor is made from its fruit. A widow must mourn her husband for a month, and can then marry again. But she may not marry her late husband’s brother, nor his first cousin, nor any member of her father’s sept. Divorce is allowed, but no man will divorce his wife unless she leaves him of her own accord or is known to be intriguing with a man of lower caste.

5. Religion

Each sept has a deity of its own who is usually some local god symbolised by a wooden post or a stone. Instances of these are Kondrāj of Santoshpur represented by a wooden pillar carved into circular form at the top; Chikat Rāj of Bijāpur by two bamboos six feet in length leaning against a wall; Kaunam Rāj of Gongla by a stone image, and at fairs by a bamboo with peacock’s feathers tied at the top. They offer incense, rice and a fowl to their ancestors in their own houses in Chait (March) at the new year, and at the festival of the new rice in Bhādon (August). At the sowing festival they go out hunting, and those who return empty-handed think they will have ill-luck. Each tenant also worships the earth-goddess, whose image is then decorated with flowers and vermilion. He brings a goat, and rice is placed before it at her shrine. If the animal eats the sacrifice is held to be accepted, but if not it is returned to the owner, and it is thought that some misfortune will befall him. The heads of all the goats offered are taken by the priest and the bodies returned to the worshippers to be consumed at a feast. Each village has also its tutelary god, having a hut to himself. Inside this a post of mahua wood is fixed in the ground and roughly squared, and a peg is driven into it at the top. The god is represented by another bamboo peg about two inches long, which is first worshipped in front of the post and then suspended from it in a receptacle. In each village the smallpox goddess is also present in the form of a stone, either with or without a hut over it. A Jangam or devotee of the Lingāyat sect is usually the caste priest, and at a funeral he follows the corpse ringing his bell. If a man is put out of caste through getting maggots in a wound or being beaten by a shoe, he must be purified by the Jangam. The latter rubs some ashes on his own body and places them in the offender’s mouth, and gives him to drink some water from his own lota in place of water from a sacred river. For this the offender pays a fee of five rupees and a calf to the Jangam and must also give a feast to the caste. The dead are either buried or burnt, the head being placed to the east. The eldest son has his head and face shaved on the death of the father of the family, and the youngest on that of the mother.

6. Names

A child is named on the seventh or eighth day after birth by the old women. If it is much given to crying they consider the name unsuitable and change it, repeating those of deceased relatives. When the child stops crying at the mention of a particular name, they consider that the relative mentioned has been born again in the child and name it after him. Often the name of the sept is combined with the personal name as Lingam-Lachha, Lingam-Kachchi, Pānki-Samāya, Pānki-Ganglu, Pānki-Buchcham, Nāgul-Sama, Nāgul-Mutta.

7. Magical devices

When a man wishes to destroy an enemy he makes an image of him with earth and offers a pig and goat to the family god, praying for the enemy’s destruction. Then the operator takes a frog or a tree-lizard which has been kept ready and breaks all its limbs, thinking that the limbs of his enemy will similarly be broken and that the man will die. Or he takes some grains of kossa, a small millet, and proceeds to a sāj192 or mahua tree. A pigeon is offered to the tree and to the family god, and both are asked to destroy the foe. The man then ascends the tree, and muttering incantations throws the grains in the direction of his enemy thinking that they will enter his body and destroy him. To counteract these devices a man who thinks himself bewitched calls in the aid of a wizard, who sucks out of his body the grains or other evil things which have been caused to enter it as shown above. Occasionally a man will promise a human sacrifice to his god. For this he must get some hair or a piece of cloth belonging to somebody else and wash it in water in the name of the god, who may then kill the owner of the hair or cloth and thus obtain the sacrifice. Or the sacrificer may pick a quarrel and assault the other person so as to draw blood from him. He picks up a drop or two of the blood and offers it to the deity with the same end in view.

8. Occupation

The caste are cultivators and farmservants, and are, as a rule, very poor, living from hand to mouth. They practise shifting cultivation and are too lazy to grow the more valuable crops. They eat grain twice a day during the four months from October to January only, and at other times eke out their scanty provision with edible roots and leaves, and hunt and fish in the forest like the Muria and Māria Gonds.

Jogi

[Bibliography: Sir E. Maclagan’s Punjab Census Report (1891); Mr. Crooke’s Tribes and Castes, articles Jogi, Kānphata and Aghorpanthi; Mr. Kitts’ Berār Census Report (1881); Professor Oman’s Mystics, Ascetics and Saints of India (London: T. Fisher Unwin).]

1. The Yoga philosophy

Jogi, Yogi.—The well-known order of religious mendicants and devotees of Siva. The Jogi or Yogi, properly so called, is a follower of the Yoga system of philosophy founded by Pātanjali, the main characteristics of which are a belief in the power of man over nature by means of austerities and the occult influences of the will. The idea is that one who has obtained complete control over himself, and entirely subdued all fleshly desires, acquires such potency of mind and will that he can influence the forces of nature at his pleasure. The Yoga philosophy has indeed so much sub-stratum of truth that a man who has complete control of himself has the strongest will, and hence the most power to influence others, and an exaggerated idea of this power is no doubt fostered by the display of mesmeric control and similar phenomena. The fact that the influence which can be exerted over other human beings through their minds in no way extends to the physical phenomena of inanimate nature is obvious to us, but was by no means so to the uneducated Hindus, who have no clear conceptions of the terms mental and physical, animate and inanimate, nor of the ideas connoted by them. To them all nature was animate, and all its phenomena the results of the actions of sentient beings, and hence it was not difficult for them to suppose that men could influence the proceedings of such beings. And it is a matter of common knowledge that savage peoples believe their magicians to be capable of producing rain and fine weather, and even of controlling the course of the sun.193 The Hindu sacred books indeed contain numerous instances of ascetics who by their austerities acquired such powers as to compel the highest gods themselves to obedience.

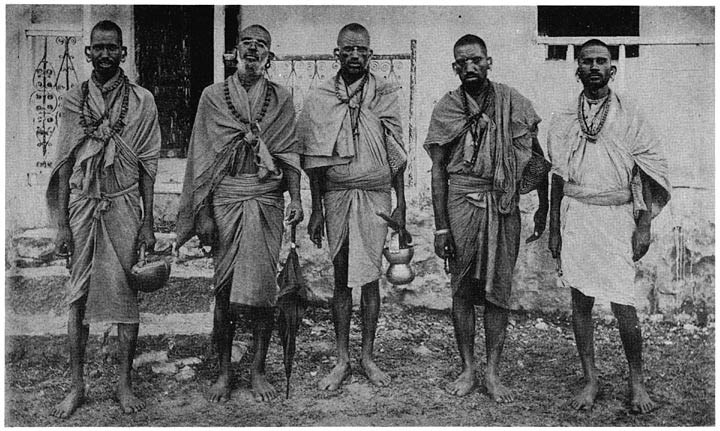

Jogi mendicants of the Kanphata sect

2. Abstraction of the senses or autohypnotism

The term Yoga is held to mean unity or communion with God, and the Yogi by virtue of his painful discipline and mental and physical exercises considered himself divine. “The adept acquires the knowledge of everything past and future, remote or hidden; he divines the thoughts of others, gains the strength of an elephant, the courage of a lion, and the swiftness of the wind; flies into the air, floats in the water, and dives into the earth, contemplates all worlds at one glance and performs many strange things.”194

The following excellent instance of the pretensions of the Yogis is given by Professor Oman:195 “Wolff went also with Mr. Wilson to see one of the celebrated Yogis who was lying in the sun in the street, the nails of whose hands were grown into his cheeks and a bird’s nest upon his head. Wolff asked him, ‘How can one obtain the knowledge of God?’ He replied, ‘Do not ask me questions; you may look at me, for I am God.’

“It is certainly not easy at the present day,” Professor Oman states,196 “for the western mind to enter into the spirit of the so-called Yoga philosophy; but the student of religious opinions is aware that in the early centuries of our era the Gnostics, Manichæans and Neo-Platonists derived their peculiar tenets and practices from the Yoga-vidya of India, and that at a later date the Sufi philosophy of Persia drew its most remarkable ideas from the same source.197 The great historian of the Roman Empire refers to the subject in the following passage: “The Fakīrs of India and the monks of the Oriental Church, were alike persuaded that in total abstraction of the faculties of the mind and body, the pure spirit may ascend to the enjoyment and vision of the Deity. The opinion and practice of the monasteries of Mount Athos will be best represented in the words of an abbot, who flourished in the eleventh century: ‘When thou art alone in thy cell,’ says the ascetic teacher, ‘Shut thy door, and seat thyself in a corner, raise thy mind above all things vain and transitory, recline thy beard and chin on thy breast, turn thine eyes and thy thoughts towards the middle of the belly, the region of the navel, and search the place of the heart, the seat of the soul. At first all will be dark and comfortless; but if you persevere day and night, you will feel an ineffable joy; and no sooner has the soul discovered the place of the heart, than it is involved in a mystic and ethereal light.’ This light, the production of a distempered fancy, the creature of an empty stomach and an empty brain, was adored by the Quietists as the pure and perfect essence of God Himself.”198

“Without entering into unnecessary details, many of which are simply disgusting, I shall quote, as samples, a few of the rules of practice required to be followed by the would-be Yogi in order to induce a state of Samādhi—hypnotism or trance—which is the condition or state in which the Yogi is to enjoy the promised privileges of Yoga. The extracts are from a treatise on the Yoga philosophy by Assistant Surgeon Nobin Chander Pāl.”199

“Place the left foot upon the right thigh, and the right foot upon the left thigh; hold with the right hand the right great toe and with the left hand the left great toe (the hands coming from behind the back and crossing each other); rest the chin on the interclavicular space, and fix the sight on the tip of the nose.

“Inspire through the left nostril, fill the stomach with the inspired air by the act of deglutition, suspend the breath, and expire through the right nostril. Next inspire through the right nostril, swallow the inspired air, suspend the breath, and finally expire through the left nostril.

“Be seated in a tranquil posture, and fix your sight on the tip of the nose for the space of ten minutes.

“Close the ears with the middle fingers, incline the head a little to the right side and listen with each ear attentively to the sound produced by the other ear, for the space of ten minutes.

“Pronounce inaudibly twelve thousand times the mystic syllable Om, and meditate upon it daily after deep inspirations.

“After a few forcible inspirations swallow the tongue, and thereby suspend the breath and deglutate the saliva for two hours.

“Listen to the sounds within the right ear abstractedly for two hours, with the left ear.

“Repeat the mystic syllable Om 20,736,000 times in silence and meditate upon it.

“Suspend the respiratory movements for the period of twelve days, and you will be in a state of Samādhi.”

Another account of a similar procedure is given by Buchanan:200 “Those who pretend to be eminent saints perform the ceremony called Yoga, described in the Tantras. In the accomplishment of this, by shutting what are called the nine passages (dwāra, lit. doors) of the body, the votary is supposed to distribute the breath into the different parts of the body, and thus to obtain the beatific vision of various gods. It is only persons who abstain from the indulgence of concupiscence that can pretend to perform this ceremony, which during the whole time that the breath can be held in the proper place excites an ecstasy equal to whatever woman can bestow on man.”

3. Breathing through either nostril

It is clear that the effect of some of the above practices is designed to produce a state of mind resembling the hypnotic trance. The Yogis attach much importance to the effect of breathing through one or the other nostril, and this is also the case with Hindus generally, as various rules concerning it are prescribed for the daily prayers of Brāhmans. To have both nostrils free and be breathing through them at the same time is not good, and one should not begin any business in this condition. If one is breathing only through the right nostril and the left is closed, the condition is propitious for the following actions: To eat and drink, as digestion will be quick; to fight; to bathe; to study and read; to ride on a horse; to work at one’s livelihood. A sick man should take medicine when he is breathing through his right nostril. To be breathing only through the left nostril is propitious for the following undertakings: To lay the foundations of a house and to take up residence in a new house; to put on new clothes; to sow seed; to do service or found a village; to make any purchase. The Jogis practise the art of breathing in this manner by stopping up their right and left nostril alternately with cotton-wool and breathing only through the other. If a man comes to a Brāhman to ask him whether some business or undertaking will succeed, the Brāhman breathes through his nostrils on to his hand; if the breath comes through the right nostril the omen is favourable and the answer yes; if through the left nostril the omen is unfavourable and the answer no.

4. Self-torture of the Jogis

The following account of the austerities of the Jogis during the Mughal period is given by Bernier:201 “Among the vast number and endless variety of Fakīrs or Dervishes, and holy men or Gentile hypocrites of the Indies, many live in a sort of convent, governed by superiors, where vows of chastity, poverty, and submission are made. So strange is the life led by these votaries that I doubt whether my description of it will be credited. I allude particularly to the people called ‘Jogis,’ a name which signifies ‘United to God.’ Numbers are seen day and night, seated or lying on ashes, entirely naked; frequently under the large trees near talābs or tanks of water, or in the galleries round the Deuras or idol temples. Some have hair hanging down to the calf of the leg, twisted and entangled into knots, like the coats of our shaggy dogs. I have seen several who hold one, and some who hold both arms perpetually lifted above the head, the nails of their hands being twisted and longer than half my little finger, with which I measured them. Their arms are as small and thin as the arms of persons who die in a decline, because in so forced and unnatural a position they receive not sufficient nourishment, nor can they be lowered so as to supply the mouth with food, the muscles having become contracted, and the articulations dry and stiff. Novices wait upon these fanatics and pay them the utmost respect, as persons endowed with extraordinary sanctity. No fury in the infernal regions can be conceived more horrible than the Jogis, with their naked and black skin, long hair, spindle arms, long twisted nails, and fixed in the posture which I have mentioned.

“I have often met, generally in the territory of some Rāja, bands of these naked Fakīrs, hideous to behold. Some have their arms lifted up in the manner just described; the frightful hair of others either hung loosely or was tied and twisted round their heads; some carried a club like the Hercules, others had a dry and rough tiger-skin thrown over their shoulders. In this trim I have seen them shamelessly walk stark naked through a large town, men, women, and girls looking at them without any more emotion than may be created when a hermit passes through our streets. Females would often bring them alms with much devotion, doubtless believing that they were holy personages, more chaste and discreet than other men.

“Several of these Fakīrs undertake long pilgrimages not only naked but laden with heavy iron chains, such as are put about the legs of elephants. I have seen others who, in consequence of a particular vow, stood upright during seven or eight days without once sitting or lying down, and without any other support than might be afforded by leaning forward against a cord for a few hours in the night; their legs in the meantime were swollen to the size of their thighs. Others, again, I have observed standing steadily, whole hours together, upon their hands, the head down and the feet in the air. I might proceed to enumerate various other positions in which these unhappy men place their body, many of them so difficult and painful that they could not be imitated by our tumblers; and all this, let it be recollected is performed from an assumed feeling of piety, of which there is not so much as the shadow in any part of the Indies.”

5. Resort to them for oracles

The forest ascetics were credited with prophetic powers, and were resorted to by Hindu princes to obtain omens and oracles on the brink of any important undertaking. This custom is noticed by Colonel Tod in the following passage describing the foundation of Jodhpur:202 “Like the Druids of the cells, the vana-perist Jogis, from the glades of the forest (vana) or recess in the rocks (gopha), issue their oracles to those whom chance or design may conduct to their solitary dwellings. It is not surprising that the mandates of such beings prove compulsory on the superstitious Rājpūt; we do not mean those squalid ascetics who wander about India and are objects disgusting to the eye, but the genuine Jogi, he who, as the term imports, mortifies the flesh, till the wants of humanity are restricted merely to what suffices to unite matter with spirit, who had studied and comprehended the mystic works and pored over the systems of philosophy, until the full influence of Maia (illusion) has perhaps unsettled his understanding; or whom the rules of his sect have condemned to penance and solitude; a penance so severe that we remain astonished at the perversity of reason which can submit to it. We have seen one of these objects, self-condemned never to lie down during forty years, and there remained but three to complete the term. He had travelled much, was intelligent and learned, but, far from having contracted the moroseness of the recluse, there was a benignity of mien and a suavity and simplicity of manner in him quite enchanting. He talked of his penance with no vainglory and of its approaching term without any sensation. The resting position of this Druid (vana-perist) was by means of a rope suspended from the bough of a tree in the manner of a swing, having a cross-bar, on which he reclined. The first years of this penance, he says, were dreadfully painful; swollen limbs affected him to that degree that he expected death, but this impression had long since worn off. To these, the Druids of India, the prince and the chieftain would resort for instruction. Such was the ascetic who recommended Joda to erect his castle of Jodhpur on the ‘Hill of Strife’ (Jodagīr), a projecting elevation of the same range on which Mundore was placed, and about four miles south of it.”

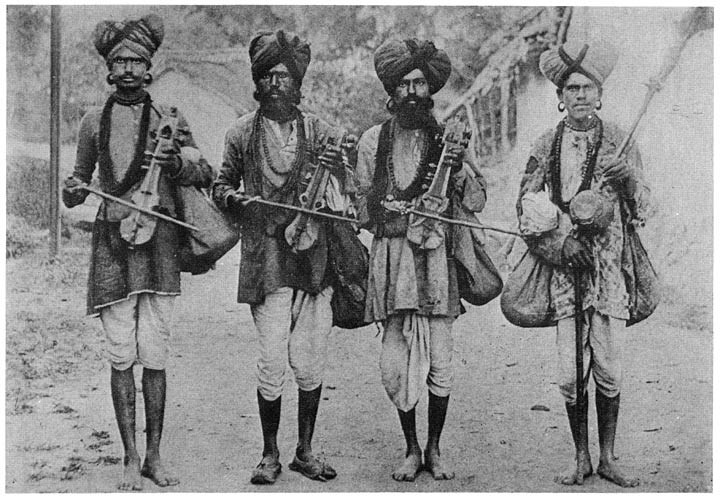

Jogi musicians with sārangi or fiddle

6. Divisions of the order

About 15,000 Jogis were returned from the Central Provinces in 1911. They are said to be divided into twelve Panths or orders, each of which venerates one of the twelve disciples of Gorakhnāth. But, as a rule, they do not know the names of the Panths. Their main divisions are the Kanphata and Aughar Jogis. The Kanphatas,203 as the name denotes, pierce their ears and wear in them large rings (mundra), generally of wood, stone or glass; the ears of a novice are pierced by the Guru, who gets a fee of Rs. 1–4. The earring must thereafter always be worn, and should it be broken must be replaced temporarily by a model in cloth before food is taken. If after the ring has been inserted the ear tears apart, they say that the man has become useless, and in former times he was buried alive. Now he is put out of caste, and no tomb is erected over him when he dies. It is said that a man cannot become a Kanphata all at once, but must first serve an apprenticeship of twelve years as an Aughar, and then if his Guru is satisfied he will be initiated as a Kanphata. The elect among the Kanphatas are known as Darshani. These do not go about begging, but remain in the forest in a cave or other abode, and the other Jogis go there and pay their respects; this is called darshan, the term used for visiting a temple and worshipping the idol. These men only have cooked food when their disciples bring it to them, otherwise they live on fruits and roots. The Aughars do not pierce their ears, but have a string of black sheep’s wool round the neck to which is suspended a wooden whistle called nadh; this is blown morning and evening and before meals.204 The names of the Kanphatas end in Nāth and those of the Aughars in Dās.

7. Hair and clothes

When a novice is initiated all the hair of his head is shaved, including the scalp-lock. If the Ganges is at hand the Guru throws the hair into the Ganges, giving a great feast to celebrate the occasion; otherwise he keeps the hair in his wallet until he and his disciple reach the Ganges and then throws it into the river and gives the feast. After this the Jogi lets all his hair grow until he comes to some great shrine, when he shaves it off clean and gives it as an offering to the god. The Jogis wear clothes coloured with red ochre like the Jangams, Sanniāsis and all the Sivite orders. The reddish colour perhaps symbolises blood and may denote that the wearers still sacrifice flesh and consume it. The Vaishnavite orders usually wear white clothes, and hence the Jogis call themselves Lāl Pādris (red priests), and they call the Vaishnava mendicants Sīta Pādris, apparently because Sīta is the consort of Rāma, the incarnation of Vishnu. When a Jogi is initiated the Guru gives him a single bead of rudrāksha wood which he wears on a string round his neck. He is not branded, but afterwards, if he visits the temple of Dwārka in Gujarāt, he is branded with the mark of the conch-shell on the arm; or if he goes on pilgrimage to the shrine of Badri-Nārāyan in the Himālayas he is branded on the chest. Copper bangles are brought from Badri-Nārāyan and iron ones from the shrine of Kedārnāth. A necklace of small white stones, like juāri-seeds, is obtained from the temple of Hinglāj in the territories of the Jām of Lāsbela in Beluchistān. During his twelve years’ period as a Brahmachari or acolyte, a Jogi will make either one or three parikramas of the Nerbudda; that is, he walks from the mouth at Broach to the source at Amarkantak on one side of the river and back again on the other side, the journey usually occupying about three years. During each journey he lets his hair grow and at the end of it makes an offering of all except the choti or scalp-lock to the river. Even as a full Jogi he still retains the scalp-lock, and this is not finally shaved off until he turns into a Sanniāsi or forest recluse. Other Jogis, however, do not merely keep the scalp-lock but let their hair grow, plaiting it with ropes of black wool over their heads into what is called the jata, that is an imitation of Siva’s matted locks.205