полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

9. Going-away ceremony

After the wedding if the bride is grown up she lives with her husband at once; but if she is a child she goes back to her parents until her adolescence, when the ceremony of Pathoni or ‘Going away’ is performed. On this occasion some people from the bridegroom’s home go to fetch her and their number must be even, so that when she returns with them the party may be an odd one, which is lucky. They take a new cloth for the bride and stay the night at her house; next morning the bride’s parents put some rice, pulse, oil and a comb in a basket for her, and she sets out with the party, wearing her new cloth. But when she gets outside the village this is taken off her and placed in the basket, which she has to carry on her head as far as her husband’s house. As she enters his village the people stretch a rope across the way and prevent her passage until her father-in-law gives them a present. On arriving at his house her feet are washed by her mother-in-law, and she is then made to cook the food brought in her basket. After a fortnight she again goes back to her parents’ house and stays with them for another year, before finally taking up her abode with her husband. It has been remarked that this return of a married woman to her parents’ house for such lengthened periods is likely to be a pregnant source of immorality, and the advantage of the custom has been questioned; the explanation may perhaps be that it is an outcome of the joint family system by which young married couples live with the bridegroom’s parents, and that the object is to accustom the girl gradually to the habits of a fresh household and the yoke, necessarily irksome, of her mother-in-law. The proverb with reference to a young wife, ‘If your husband loves you your mother-in-law can do nothing,’ indicates how formidable this may be in the event of any cooling of marital affection; and it is well known that if she does not please her husband’s family a young wife may be treated as little better than a slave. To throw a young girl, therefore, into a family of complete strangers is probably too severe a trial, and this is the reason of the goings and returnings of the bride after her wedding between her husband’s home and her own.

10. Widow-marriage and divorce

The remarriage of a widow must be held during the bright fortnight of the month, and on any odd day of the fortnight excluding the first. The couple are seated together on a yoke in a part of the courtyard cleaned with cowdung, and their clothes are tied together, while the husband rubs vermilion on his wife’s hair. A bachelor should not take a widow in marriage, and if he does so he must at the same time also wed a maiden with the regular ceremony, as otherwise he is likely after death to become a masāan or evil spirit. In order to avoid this contingency a bachelor who espouses a widow in Kānker is first wedded to a spear. Turmeric and oil are rubbed on his body and on the spear, and he walks round it seven times. Divorce is freely permitted in Chhattīsgarh at the instance of either party and for the most trivial reasons, as a mere allegation of disagreement; but if a husband puts away his wife when she has not been unfaithful to him he must give her something for her support. In some localities no ceremony is performed at all, but a wife or husband who tires of wedlock simply leaves the other as the case may be. In Bastar a wife cannot divorce her husband. A divorced woman does not break her glass bangles until she marries again, when new ones are given to her by her second husband.

11. Religion

A large proportion of the Halbas of Chhattīsgarh belong to the Kabīrpanthi sect. These are known as Kabīrhas and abjure the consumption of flesh and alcoholic liquor; while the others who indulge in these articles are known as Sakatha or Sakta, that is, a worshipper of Devi or Durga. These latter, however, also revere all the village godlings of Chhattīsgarh.

12. Disposal of the dead

The dead are always buried by the Kabīrpanthis and usually by other Halbas, cremation being reserved by the latter as a special mark of respect for elders and heads of families. A dead body is wrapped in a new white cloth and laid on an inverted cot. The Kabīrpanthis lay plantain leaves at the sides of the cot and over the body to cover it. One of the mourners carries a burning cowdung cake with the party. Before burial the thread which every male wears round his waist is broken, the clothes are taken off the corpse and given to a sweeper, and the body is wrapped in the shroud and laid in the grave, salt being sprinkled under and over it. If the dead body should be touched by any person of another caste, the deceased’s family has to pay a fine or give a penal caste-feast. After the interment the mourners bathe and return to the deceased’s house in their wet clothes. Before entering it they wash their feet in water, which is kept for that purpose at the door, and chew the leaves of the nīm tree (Melia indica). They smoke their chongis or leaf-pipes and console the deceased’s family and then return home, washing their feet again and changing their clothes at their own houses. On the third day, known as Tīj Nahān, the male members of the family with the relatives and mourners walk in Indian file to a river or tank, where they are all shaved by the barber, the sons of the dead man or woman having the entire head and face cleared of hair, while in the case of other relatives, the scalp-lock and moustache may be left, and the mourning friends are only shaved as on ordinary occasions. For his services the barber receives a cow or a substantial cash present, which he divides with the washerman. The latter subsequently washes all clothes worn at the funeral and on this occasion. On the Akti festival, or commencement of the agricultural year, libations of water and offerings of urad145 cakes are made to the spirits of ancestors. A feast is given to women in honour of all departed female ancestors on the ninth day of the Pitripaksh or mourning fortnight of Kunwār (September), and feasts for male ancestors may be held on the same day of the fortnight as that on which they died at any other time of the year.146 Such observances are practised only by the well-to-do. Nothing is done for persons who die before their marriage or without children, unless they trouble some member of the family and appear in a dream to demand that these honours be paid to them. During an epidemic of cholera all funeral and mourning ceremonies are suspended, and a general purification of the village takes place on its conclusion.

13. Propitiating the spirits of those who have died a violent death

If a person has been killed by a tiger, the people go out, and if any remains of the body are found, these are burnt on the spot. The Baiga is then invoked to bring back the spirit of the deceased, a most essential precaution as will shortly be seen. In order to do this he suspends a copper ring on a long thread above a vessel of water and then burns butter and sugar on the fire, muttering incantations, while the people sing songs and call on the spirit of the dead man to return. The thread swings to and fro, and at length the copper ring falls into the pot, and this is taken as a sign that the spirit has come and entered the vessel. The mouth of this is immediately covered and it is buried or kept in some secure place. The people believe that unless the dead man’s spirit is secured it will accompany the tiger and lure solitary travellers to destruction. This is done by calling out and offering them tobacco to smoke, and when they proceed in the direction of the voice the tiger springs out and kills them. And they think that a tiger directed in this manner grows fiercer and fiercer with every person whom it kills. When somebody has been killed by a tiger the relatives will not even remove the ornaments from the corpse, for they think that these would constitute a link by which its spirit would cause the tiger to track them down. The malevolence thus attributed to persons killed by tigers is explained by their bitter wrath at having encountered such an untimely death and consequent desire to entice others to the same.

14. Impurity of women

During the monthly period of menstruation women are spoken of as ‘Mund maili’ or having the head dirty, and are considered to be impure for four or five days, for which time they sleep on the ground and not on cots. In Kānker they are secluded in a separate room, and forbidden to cook or to touch the clothes or persons of other members of the family. They must not walk on a ploughed field, nor will the men of their family drive the plough or sow seed during the time of their impurity. On the fifth day they wash their heads with earth and boil their clothes in water mixed with wood ashes. Cloth stained with the menstrual blood is usually buried underground; if it is burnt it is supposed that the woman to whom it belonged will become barren, and if a barren woman should swallow the ashes of the cloth the fertility of its owner would be transferred to her.

15. Childbirth

When pregnant women experience longings for strange kinds of food, it is believed that these really come from the child in the womb and must be satisfied if its development is not to be retarded. Consequently in the fifth month of a wife’s first pregnancy, or shortly before delivery, her mother takes to her various kinds of rich food and feeds her with them. It is a common custom also for pregnant women, driven by perverted appetite, to eat earth of a clayey texture, or the ordinary black cotton soil, or dried clay scraped off the walls of houses, or the ashes of burnt cowdung cakes. This is done by low-caste women in most parts of the Province, and if carried to excess leads to severe intestinal derangement which may prove fatal. A pregnant woman must not cross a river or eat anything with a knife, and she must observe various precautions against the machinations of witches. At the time of delivery the woman sits on the ground and is attended by a midwife, who may be a Chamār, Mahār or Gānda by caste. The navel cord is burnt in the lying-in room, but the after-birth, known as Phul, is usually buried in a rubbish pit outside the house. The portion of the cord attached to the child’s body is also burnt when it falls off, but in the northern Districts it is preserved and used as a cure for the child if it suffers from sore eyes. If a woman who has borne only girl children can obtain the dried navel-string of a male child and swallow it, they believe that she will have a son, and that the mother of the boy will henceforth bear only daughters. This is the reason why the cord is carefully secreted and not simply thrown away. In Bastar on the sixth or naming day the female relatives and friends of the family are invited to take food at the house. The father touches the feet of the child with blades of dūb grass (Cynodon dactylon) steeped first in milk or melted butter, then in sandal-paste, and finally in water, and each time passes the blade over his head as a mark of respect. The blades of grass are afterwards thrown over the roof of the house, so that they may not be trampled under foot. The women guests then bring leaf-cups containing rice and a few copper coins, which they offer to the mother, the younger ones bowing before her with a prayer that the child may grow as old as the speaker. All the women kiss the child, and the elder ones the mother also. The offerings of rice and coins are taken by the midwife.

16. Names

The names of the Halbas are of the ordinary type found in Chhattīsgarh, but at present they often add the termination Sinha or Singh in imitation of the Rājpūts. Two names are sometimes given, one for daily use and the other for comparison with that of the girl when the marriage is to be arranged. As already seen, either the bride’s or bridegroom’s name may be changed to make their union auspicious. When a daughter-in-law comes into her husband’s house she is usually not called by her own name, but by some nickname or that of her home, as Jabalpurwāli, Raipurwāli (she who comes from Jabalpur or Raipur), and so on. Sometimes men of the caste are addressed by the name of the clan or section and not by their own. A woman must not utter the names of her husband, his parents or brothers, nor of the sons of his elder brother and his sisters. But for these last as well as for her own son-in-law she may invent fictitious names. These rules she observes to show her respect for her husband’s relatives. A child must not be called by name at night, because if an owl hears the name and repeats it the child will probably die. The owl is everywhere regarded as a bird of the most evil omen. Its hoot is unlucky, and a house in which its nest is built will be destroyed or deserted. If it perches on the roof of a house and hoots, some one of the family will probably fall ill, or if a member of the household is already ill, he or she will probably die.

17. Social status

The social customs of the caste present some differences. In Bastar, where they have a fairly high status, the Purāit Halbas abstain from liquor, though they will eat the flesh of clean animals and of the wild pig. The Halbas of Raipur on the other hand, who are usually farmservants, will eat fowls, pigs and rats, and abstain only from beef and the leavings of others. In Bastar, Sunārs, Kurmis and castes of similar position will take water from the hands of a Halba, and Kosaria Rāwats will eat all kinds of food with them. In Chhattīsgarh the Halbas will accept water from Telis, Kahārs and other like castes, and will also allow any of them to become a Halba. In Chhattīsgarh they will take even food cooked with water from the hands of a man of these castes, provided that they are not in their own villages. These differences of custom are probably due to the varying social status of the caste. In Bastar they hold land and behave accordingly, while in Chhattīsgarh they are only labourers. They do not employ Brāhmans for ceremonial purposes but have their own caste priest, known as Joshi, while among the Kabīrpanthis the local Mahant or Bairāgi of the sect takes his place.

18. Caste panchāyat

They have a caste panchāyat or committee, the headman of which is known as Kursha; he has jurisdiction over ten or twenty villages, and is usually chosen from the Kotwār, Chanap or Nāik sections. It is the duty of the men of these sections to scatter the sonpāni or ‘water of gold’147 as an act of purification over persons who have been temporarily put out of caste for social offences. They are also the first to eat food with such offenders on readmission to social intercourse, and thereby take the sins of these persons upon their own heads. In order to counteract the effect of this the purifier usually asks three or four other men to eat with him at his own house, and passes on a part of his burden to them. For such duties he receives a payment of money varying from four annas to a rupee and a half. Among the offences punished with temporary exclusion from caste are those of rearing the lac insect and tasar silk cocoons, probably because such work involves the killing of the insects and caterpillars which produce the dye and silk. In Bastar a man loses his caste if he is beaten with a shoe except by a Government servant, and is not readmitted to it. If a man seduces a married woman and is beaten with a shoe by her husband he is also finally expelled from caste. But happily, Mr. Panda Baijnāth remarks, shoes are very scarce in the State, and hence such cases do not often arise. They never yoke cows to the plough as other castes do in Bastar, nor do they tie up two cows with the same rope.

19. Dress

The dress of the Halbas, as of other Chhattīsgarh castes, is scanty, and most of them have only a short cloth about the loins and another round the shoulders. They dispense with both shoes and head-cloth, but every man must have a thread tied round his waist. To this thread in former times, Colonel Dalton remarks, the apron of leaves was not improbably suspended. The women do not wear nose-rings, spangles on the forehead or rings on the toes; but girl children have the left nostril pierced, and this must always be done on the full moon day of the month of Pūs (December). A copper ring is inserted in the nostril and worn for a few months, but must be removed before the girl’s marriage. A married woman has a cloth over her head, and smears vermilion on the parting of her hair and also on her forehead. An unmarried girl may have the copper ring already mentioned, and may place a dab of vermilion on her forehead, but must not smear it on the parting of her hair. She goes bare-headed till marriage, as is the custom in Chhattīsgarh. A widow should not have vermilion on her face at all, nor should she use glass bangles or ornaments about the ankles. She may have a string of glass beads about her neck. A woman’s cloth is usually white with a broad red border all round it. The Gonds and Halbas tie the cloth round the waist and carry the slack end from the left side behind up the back and over the head and right shoulder; while women of higher castes take the cloth from the right side over the head and left shoulder.

20. Tattooing

Girls are tattooed before marriage, usually at the age of four or five years, with dots on the left nostril and centre of the chin, and three dots in a line on the right shoulder. A girl is again tattooed after marriage, but before leaving for her husband’s house. On this occasion four pairs of parallel lines are made on the leg above the ankle, in front, behind, and on the sides. As a rule, the legs are not otherwise tattooed, nor the trunk of the body. Groups of dots, triangles and lines are made on the arms, and on the left arm is pricked a zigzag line known as the sikri or chain, the pattern of which is distinctive. Teli and Gahra (Ahīr) women also have the sikri, but in a slightly different form. The tattooing is done by a woman of the Dewar caste, and she receives some corn and the cloth worn by the girl at the time of the operation. If a child is slow in learning to walk they tattoo it on the loins above the hips, and believe that this is efficacious. Men who suffer from rheumatism also get the affected joints tattooed, and are said to experience much relief. The tattooing acts no doubt as a blister, and may produce a temporarily beneficial effect. It may be compared to the bee-sting cure for rheumatism now advocated in England. Tattooing is believed to enhance the beauty of women, and it is also said that the tattoo marks are the only ornament which will accompany the soul to the other world. From this belief it seems clear that they expect to have the same body in the after-life.

21. Occupation

Nearly all the Halbas are now engaged in agriculture as tenants and labourers. Seven zamīndāri estates are held by members of the caste, six in Bhandāra and one in Chānda, and they also have some villages in the south of the Raipur and Drūg Districts. It is probable that they obtained this property in reward for military service, at the period when they were employed in the armies of the Ratanpur kings and of the Gond dynasty of Chānda. In the forest tracts of Dhamtari they are considered the best cultivators next to the Telis, and they show themselves quite able to hold their own in the open country, where their villages are usually prosperous. In Bastar they still practise shifting cultivation, sowing their crops on burnt-out patches of forest. Though hunting is not now one of their regular occupations, Mr. Gokul Prasād describes them as catching game by the following method: Six or seven men go out together at night, tying round their feet ghunghunias or two small hollow balls of brass with stones inside which tinkle as they move, such as are worn by postal runners. They move in Indian file, the first man carrying a lantern and the others walking behind him in its shadow. They walk with measured tread, and the ghunghunias give out a rhythmical harmonious sound. Hares and other small animals are attracted by the sound, and at the same time half-blinded by the light, so that they do not see the line of men. They approach, and are knocked over or caught by the men following the leader.

Halwai

Halwai.—The occupational caste of confectioners, numbering about 3000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berār in 1911. The Halwai takes his name from halwa, a sweet made of flour, clarified butter and sugar, coloured with saffron and flavoured with almonds, raisins and pistachio-nuts.148 The caste gives no account of its origin in northern India, but it is clearly a functional group composed of members of respectable middle-class castes who adopted the profession of sweetmeat-making. The Halwais are also called Mithaihas, or preparers of sweets, and in the Uriya country are known as Guria from gur or unrefined sugar. The caste has several subdivisions with territorial names, generally derived from places in northern India, as Kanaujia from Kanauj, and Jaunpuria from Jaunpur; others are Kāndu, a grain-parcher, and Dobisya, meaning two score. One of the Guria subdivisions is named Haldia from haldi, turmeric, and members of this subcaste are employed to prepare the mahāprasād or cooked rice which is served at the temple of Jagannāth and which is eaten by all castes together without scruple. The Gurias have exogamous divisions or bargas, the names of which are generally functional, as Darbān, door-keeper; Sarāf, treasurer; Bhitarya, one who looks to household affairs, and others. Marriage within the barga is forbidden, but the union of first cousins is not prohibited. Marriage may be infant or adult. A girl who has a liaison with a man of the caste may be wedded to him by the form used for the remarriage of a widow, but if she goes wrong with an outsider she is finally expelled. Widow-marriage is allowed, and divorce may be effected for misconduct on the part of the wife.

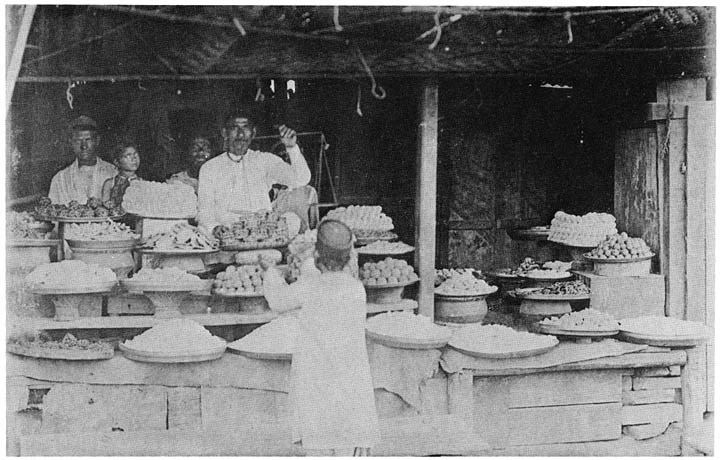

Halwai or confectioner’s shop

The social standing of the Halwai is respectable. “His art,” says Mr. Nesfield,149 “implies rather an advanced state of culture, and hence his rank in the social scale is a high one. There is no caste in India which considers itself too pure to eat what a confectioner has made. In marriage banquets it is he who supplies a large part of the feast, and at all times and seasons the sweetmeat is a favourite food to a Hindu requiring a temporary refreshment. There is a kind of bread called puri, consisting of wheaten dough fried in melted butter, which is taken as a substitute for the chapāti or wheaten pancake by travellers and others who happen to be unable to have their bread cooked at their own fire, and is made by the Halwais.”

The real reason why the Halwai occupies a good position perhaps simply results from the necessity that other castes should be able to take cakes from him. Among the higher castes food cooked with water should not be eaten except at the hearth after this has been specially cleansed and spread with cowdung, and those who are to eat have bathed and otherwise purified themselves. But as the need continuously arises for travellers and others to take a meal abroad where they cannot cook it for themselves, sweetmeats and cakes made without water are permitted to be eaten in this way, and the Halwai, as the purveyor of these, has been given the position of a pure caste from whose hands a Brāhman can take water. In a similar manner, water may be taken from the hands of the Dhīmar who is a household servant, the Kahār or palanquin-bearer, the Barai or betel-leaf seller, and the Bharbhūnja or rice-parcher, although some of these castes have a very low origin and occupy the humble position of menial servants.

The Halwai’s shop is one of the most familiar in an Indian bazār, and in towns a whole row of them may be seen together, this arrangement being doubtless adopted for the social convenience of the caste-fellows, though it might be expected to decrease the custom that they receive. His wares consist of trays full of white and yellow-coloured sweetmeats and cakes of flour and sugar, very unappetising to a European eye, though Hindu boys show no lack of appreciation of them. The Hindus are very fond of sweet things, which is perhaps a common trait of an uneducated palate. Hindu children will say that such sweets as chocolate almonds are too bitter, and their favourite drink, sherbet, is simply a mixture of sugar and water with some flavouring, and seems scarcely calculated to quench the thirst produced by an Indian hot weather. Similarly their tea is so sweetened with sugar and spices as to be distasteful to a European.