полная версия

полная версияAriadne Florentina: Six Lectures on Wood and Metal Engraving

Considered, however, as a means of relieving more delicate textures, they are in some degree legitimate, being, in fact, a kind of chasing or jagging one part of the plate surface in order to throw out the delicate tints from the rough field. But the same effect was produced with less pains, and far more entertainment to the eye, by the older engravers, who employed purely ornamental variations of line; thus in Plate IV., opposite § 137, the drapery is sufficiently distinguished from the grass by the treatment of the latter as an ornamental arabesque. The grain of wood is elaborately engraved by Marc Antonio, with the same purpose, in the plate given in your Standard Series.

118. Next, however, you observe what difference of texture and force exists between the smooth, continuous lines themselves, which are all really engraved. You must take some pains to understand the nature of this operation.

The line is first cut lightly through its whole course, by absolute decision and steadiness of hand, which you may endeavor to imitate if you like, in its simplest phase, by drawing a circle with your compass-pen; and then, grasping your penholder so that you can push the point like a plow, describing other circles inside or outside of it, in exact parallelism with the mathematical line, and at exactly equal distances. To approach, or depart, with your point at finely gradated intervals, may be your next exercise, if you find the first unexpectedly easy.

119. When the line is thus described in its proper course, it is plowed deeper, where depth is needed, by a second cut of the burin, first on one side, then on the other, the cut being given with gradated force so as to take away most steel where the line is to be darkest. Every line of gradated depth in the plate has to be thus cut eight or ten times over at least, with retouchings to smooth and clear all in the close. Jason has to plow his field ten-furrow deep, with his fiery oxen well in hand, all the while.

When the essential lines are thus produced in their several directions, those which have been drawn across each other, so as to give depth of shade, or richness of texture, have to be farther enriched by dots in the interstices; else there would be a painful appearance of network everywhere; and these dots require each four or five jags to produce them; and each of these jags must be done with what artists and engravers alike call 'feeling,'—the sensibility, that is, of a hand completely under mental government. So wrought, the dots look soft, and like touches of paint; but mechanically dug in, they are vulgar and hard.

120. Now, observe, that, for every piece of shadow throughout the work, the engraver has to decide with what quantity and kind of line he will produce it. Exactly the same quantity of black, and therefore the same depth of tint in general effect, may be given with six thick lines; or with twelve, of half their thickness; or with eighteen, of a third of the thickness. The second six, second twelve, or second eighteen, may cross the first six, first twelve, or first eighteen, or go between them; and they may cross at any angle. And then the third six may be put between the first six, or between the second six, or across both, and at any angle. In the network thus produced, any kind of dots may be put in the severally shaped interstices. And for any of the series of superadded lines, dots, of equivalent value in shade, may be substituted. (Some engravings are wrought in dots altogether.) Choice infinite, with multiplication of infinity, is, at all events, to be made, for every minute space, from one side of the plate to the other.

121. The excellence of a beautiful engraving is primarily in the use of these resources to exhibit the qualities of the original picture, with delight to the eye in the method of translation; and the language of engraving, when once you begin to understand it, is, in these respects, so fertile, so ingenious, so ineffably subtle and severe in its grammar, that you may quite easily make it the subject of your life's investigation, as you would the scholarship of a lovely literature.

But in doing this, you would withdraw, and necessarily withdraw, your attention from the higher qualities of art, precisely as a grammarian, who is that, and nothing more, loses command of the matter and substance of thought. And the exquisitely mysterious mechanisms of the engraver's method have, in fact, thus entangled the intelligence of the careful draughtsmen of Europe; so that since the final perfection of this translator's power, all the men of finest patience and finest hand have stayed content with it;—the subtlest draughtsmanship has perished from the canvas,25 and sought more popular praise in this labyrinth of disciplined language, and more or less dulled or degraded thought. And, in sum, I know no cause more direct or fatal, in the destruction of the great schools of European art, than the perfectness of modern line engraving.

122. This great and profoundly to be regretted influence I will prove and illustrate to you on another occasion. My object to-day is to explain the perfectness of the art itself; and above all to request you, if you will not look at pictures instead of photographs, at least not to allow the cheap merits of the chemical operation to withdraw your interest from the splendid human labor of the engraver. Here is a little vignette from Stothard, for instance, in Rogers' poems, to the lines,

"Soared in the swing, half pleased and half afraid,'Neath sister elms, that waved their summer shade."You would think, would you not? (and rightly,) that of all difficult things to express with crossed black lines and dots, the face of a young girl must be the most difficult. Yet here you have the face of a bright girl, radiant in light, transparent, mysterious, almost breathing,—her dark hair involved in delicate wreath and shade, her eyes full of joy and sweet playfulness,—and all this done by the exquisite order and gradation of a very few lines, which, if you will examine them through a lens, you find dividing and checkering the lip, and cheek, and chin, so strongly that you would have fancied they could only produce the effect of a grim iron mask. But the intelligences of order and form guide them into beauty, and inflame them with delicatest life.

123. And do you see the size of this head? About as large as the bud of a forget-me-not! Can you imagine the fineness of the little pressures of the hand on the steel, in that space, which at the edge of the almost invisible lip, fashioned its less or more of smile?

My chemical friends, if you wish ever to know anything rightly concerning the arts, I very urgently advise you to throw all your vials and washes down the gutter-trap; and if you will ascribe, as you think it so clever to do, in your modern creeds, all virtue to the sun, use that virtue through your own heads and fingers, and apply your solar energies to draw a skillful line or two, for once or twice in your life. You may learn more by trying to engrave, like Goodall, the tip of an ear, or the curl of a lock of hair, than by photographing the entire population of the United States of America,—black, white, and neutral-tint.

And one word, by the way, touching the complaints I hear at my having set you to so fine work that it hurts your eyes. You have noticed that all great sculptors—and most of the great painters of Florence—began by being goldsmiths. Why do you think the goldsmith's apprenticeship is so fruitful? Primarily, because it forces the boy to do small work, and mind what he is about. Do you suppose Michael Angelo learned his business by dashing or hitting at it? He laid the foundation of all his after power by doing precisely what I am requiring my own pupils to do,—copying German engravings in facsimile! And for your eyes—you all sit up at night till you haven't got any eyes worth speaking of. Go to bed at half-past nine, and get up at four, and you'll see something out of them, in time.

124. Nevertheless, whatever admiration you may be brought to feel, and with justice, for this lovely workmanship,—the more distinctly you comprehend its merits, the more distinctly also will the question rise in your mind, How is it that a performance so marvelous has yet taken no rank in the records of art of any permanent or acknowledged kind? How is it that these vignettes from Stothard and Turner,26 like the woodcuts from Tenniel, scarcely make the name of the engraver known; and that they never are found side by side with this older and apparently ruder art, in the cabinets of men of real judgment? The reason is precisely the same as in the case of the Tenniel woodcut. This modern line engraving is alloyed gold. Rich in capacity, astonishing in attainment, it nevertheless admits willful fault, and misses what it ought first to have attained. It is therefore, to a certain measure, vile in its perfection; while the older work is noble even in its failure, and classic no less in what it deliberately refuses, than in what it rationally and rightly prefers and performs.

125. Here, for instance, I have enlarged the head of one of Dürer's Madonnas for you out of one of his most careful plates.27 You think it very ugly. Well, so it is. Don't be afraid to think so, nor to say so. Frightfully ugly; vulgar also. It is the head, simply, of a fat Dutch girl, with all the pleasantness left out. There is not the least doubt about that. Don't let anybody force Albert Dürer down your throats; nor make you expect pretty things from him. Stothard's young girl in the swing, or Sir Joshua's Age of Innocence, is in quite angelic sphere of another world, compared to this black domain of poor, laborious Albert. We are not talking of female beauty, so please you, just now, gentlemen, but of engraving. And the merit, the classical, indefeasible, immortal merit of this head of a Dutch girl with all the beauty left out, is in the fact that every line of it, as engraving, is as good as can be;—good, not with the mechanical dexterity of a watch-maker, but with the intellectual effort and sensitiveness of an artist who knows precisely what can be done, and ought to be attempted, with his assigned materials. He works easily, fearlessly, flexibly; the dots are not all measured in distance; the lines not all mathematically parallel or divergent. He has even missed his mark at the mouth in one place, and leaves the mistake, frankly. But there are no petrified mistakes; nor is the eye so accustomed to the look of the mechanical furrow as to accept it for final excellence. The engraving is full of the painter's higher power and wider perception; it is classically perfect, because duly subordinate, and presenting for your applause only the virtues proper to its own sphere. Among these, I must now reiterate, the first of all is the decorative arrangement of lines.

126. You all know what a pretty thing a damask tablecloth is, and how a pattern is brought out by threads running one way in one space, and across in another. So, in lace, a certain delightfulness is given by the texture of meshed lines.

Similarly, on any surface of metal, the object of the engraver is, or ought to be, to cover it with lovely lines, forming a lace-work, and including a variety of spaces, delicious to the eye.

And this is his business, primarily; before any other matter can be thought of, his work must be ornamental. You know I told you a sculptor's business is first to cover a surface with pleasant bosses, whether they mean anything or not; so an engraver's is to cover it with pleasant lines, whether they mean anything or not. That they should mean something, and a good deal of something, is indeed desirable afterwards; but first we must be ornamental.

127. Now if you will compare Plate II. at the beginning of this lecture, which is a characteristic example of good Florentine engraving, and represents the Planet and power of Aphrodite, with the Aphrodite of Bewick in the upper division of Plate I., you will at once understand the difference between a primarily ornamental, and a primarily realistic, style. The first requirement in the Florentine work, is that it shall be a lovely arrangement of lines; a pretty thing upon a page. Bewick has a secondary notion of making his vignette a pretty thing upon a page. But he is overpowered by his vigorous veracity, and bent first on giving you his idea of Venus. Quite right, he would have been, mind you, if he had been carving a statue of her on Mount Eryx; but not when he was engraving a vignette to Æsop's fables. To engrave well is to ornament a surface well, not to create a realistic impression. I beg your pardon for my repetitions; but the point at issue is the root of the whole business, and I must get it well asserted, and variously.

Let me pass to a more important example.

128. Three years ago, in the rough first arrangement of the copies in the Educational Series, I put an outline of the top of Apollo's scepter, which, in the catalogue, was said to be probably by Baccio Bandini of Florence, for your first real exercise; it remains so, the olive being put first only for its mythological rank.

The series of engravings to which the plate from which that exercise is copied belongs, are part of a number, executed chiefly, I think, from early designs of Sandro Botticelli, and some in great part by his hand. He and his assistant, Baccio, worked together; and in such harmony, that Bandini probably often does what Sandro wants, better than Sandro could have done it himself; and, on the other hand, there is no design of Bandini's over which Sandro does not seem to have had influence.

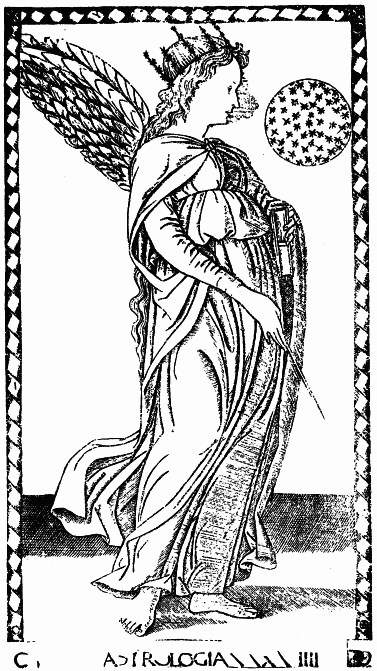

And wishing now to show you three examples of the finest work of the old, the renaissance, and the modern schools,—of the old, I will take Baccio Bandini's Astrologia, Plate III., opposite. Of the renaissance, Dürer's Adam and Eve. And of the modern, this head of the daughter of Herodias, engraved from Luini by Beaugrand, which is as affectionately and sincerely wrought, though in the modern manner, as any plate of the old schools.

III.

"At ev'ning from the top of Fésole."

129. Now observe the progress of the feeling for light and shade in the three examples.

The first is nearly all white paper; you think of the outline as the constructive element throughout.

The second is a vigorous piece of white and black—not of light and shade,—for all the high lights are equally white, whether of flesh, or leaves, or goat's hair.

The third is complete in chiaroscuro, as far as engraving can be.

Now the dignity and virtue of the plates is in the exactly inverse ratio of their fullness in chiaroscuro.

Bandini's is excellent work, and of the very highest school. Dürer's entirely accomplished work, but of an inferior school. And Beaugrand's, excellent work, but of a vulgar and non-classical school.

And these relations of the schools are to be determined by the quality in the lines; we shall find that in proportion as the light and shade is neglected, the lines are studied; that those of Bandini are perfect; of Dürer perfect, only with a lower perfection; but of Beaugrand, entirely faultful.

130. I have just explained to you that in modern engraving the lines are cut in clean furrow, widened, it may be, by successive cuts; but, whether it be fine or thick, retaining always, when printed, the aspect of a continuous line drawn with the pen, and entirely black throughout its whole course.

Now we may increase the delicacy of this line to any extent by simply printing it in gray color instead of black. I obtained some very beautiful results of this kind in the later volumes of 'Modern Painters,' with Mr. Armytage's help, by using subdued purple tints; but, in any case, the line thus engraved must be monotonous in its character, and cannot be expressive of the finest qualities of form.

Accordingly, the old Florentine workmen constructed the line itself, in important places, of successive minute touches, so that it became a chain of delicate links which could be opened or closed at pleasure.28 If you will examine through a lens the outline of the face of this Astrology, you will find it is traced with an exquisite series of minute touches, susceptible of accentuation or change absolutely at the engraver's pleasure; and, in result, corresponding to the finest conditions of a pencil line drawing by a consummate master. In the fine plates of this period, you have thus the united powers of the pen and pencil, and both absolutely secure and multipliable.

131. I am a little proud of having independently discovered, and had the patience to carry out, this Florentine method of execution for myself, when I was a boy of thirteen. My good drawing-master had given me some copies calculated to teach me freedom of hand; the touches were rapid and vigorous,—many of them in mechanically regular zigzags, far beyond any capacity of mine to imitate in the bold way in which they were done. But I was resolved to have them, somehow; and actually facsimiled a considerable portion of the drawing in the Florentine manner, with the finest point I could cut to my pencil, taking a quarter of an hour to forge out the likeness of one return in the zigzag which my master carried down through twenty returns in two seconds; and so successfully, that he did not detect my artifice till I showed it him,—on which he forbade me ever to do the like again. And it was only thirty years afterwards that I found I had been quite right after all, and working like Baccio Bandini! But the patience which carried me through that early effort, served me well through all the thirty years, and enabled me to analyze, and in a measure imitate, the method of work employed by every master; so that, whether you believe me or not at first, you will find what I tell you of their superiority, or inferiority, to be true.

132. When lines are studied with this degree of care, you may be sure the master will leave room enough for you to see them and enjoy them, and not use any at random. All the finest engravers, therefore, leave much white paper, and use their entire power on the outlines.

133. Next to them come the men of the Renaissance schools, headed by Dürer, who, less careful of the beauty and refinement of the line, delight in its vigor, accuracy, and complexity. And the essential difference between these men and the moderns is that these central masters cut their line for the most part with a single furrow, giving it depth by force of hand or wrist, and retouching, not in the furrow itself, but with others beside it.29 Such work can only be done well on copper, and it can display all faculty of hand or wrist, precision of eye, and accuracy of knowledge, which a human creature can possess. But the dotted or hatched line is not used in this central style, and the higher conditions of beauty never thought of.

In the Astrology of Bandini,—and remember that the Astrologia of the Florentine meant what we mean by Astronomy, and much more,—he wishes you first to look at the face: the lip half open, faltering in wonder; the amazed, intense, dreaming gaze; the pure dignity of forehead, undisturbed by terrestrial thought. None of these things could be so much as attempted in Dürer's method; he can engrave flowing hair, skin of animals, bark of trees, wreathings of metal-work, with the free hand; also, with labored chiaroscuro, or with sturdy line, he can reach expressions of sadness, or gloom, or pain, or soldierly strength,—but pure beauty,—never.

134. Lastly, you have the Modern school, deepening its lines in successive cuts. The instant consequence of the introduction of this method is the restriction of curvature; you cannot follow a complex curve again with precision through its furrow. If you are a dextrous plowman, you can drive your plow any number of times along the simple curve. But you cannot repeat again exactly the motions which cut a variable one.30 You may retouch it, energize it, and deepen it in parts, but you cannot cut it all through again equally. And the retouching and energizing in parts is a living and intellectual process; but the cutting all through, equally, a mechanical one. The difference is exactly such as that between the dexterity of turning out two similar moldings from a lathe, and carving them with the free hand, like a Pisan sculptor. And although splendid intellect, and subtlest sensibility, have been spent on the production of some modern plates, the mechanical element introduced by their manner of execution always overpowers both; nor can any plate of consummate value ever be produced in the modern method.

135. Nevertheless, in landscape, there are two examples in your Reference series, of insuperable skill and extreme beauty: Miller's plate, before instanced, of the Grand Canal, Venice; and E. Goodall's of the upper fall of the Tees. The men who engraved these plates might have been exquisite artists; but their patience and enthusiasm were held captive in the false system of lines, and we lost the painters; while the engravings, wonderful as they are, are neither of them worth a Turner etching, scratched in ten minutes with the point of an old fork; and the common types of such elaborate engraving are none of them worth a single frog, pig, or puppy, out of the corner of a Bewick vignette.

136. And now, I think, you cannot fail to understand clearly what you are to look for in engraving, as a separate art from that of painting. Turn back to the 'Astrologia' as a perfect type of the purest school. She is gazing at stars, and crowned with them. But the stars are black instead of shining! You cannot have a more decisive and absolute proof that you must not look in engraving for chiaroscuro.

Nevertheless, her body is half in shade, and her left foot; and she casts a shadow, and there is a bar of shade behind her.

All these are merely so much acceptance of shade as may relieve the forms, and give value to the linear portions. The face, though turned from the light, is shadowless.

Again. Every lock of the hair is designed and set in its place with the subtlest care, but there is no luster attempted,—no texture,—no mystery. The plumes of the wings are set studiously in their places,—they, also, lusterless. That even their filaments are not drawn, and that the broad curve embracing them ignores the anatomy of a bird's wing, are conditions of design, not execution. Of these in a future lecture.31

IV.

"By the Springs of Parnassus."

137. The 'Poesia,' Plate IV., opposite, is a still more severe, though not so generic, an example; its decorative foreground reducing it almost to the rank of goldsmith's ornamentation. I need scarcely point out to you that the flowing water shows neither luster nor reflection; but notice that the observer's attention is supposed to be so close to every dark touch of the graver that he will see the minute dark spots which indicate the sprinkled shower falling from the vase into the pool.

138. This habit of strict and calm attention, constant in the artist, and expected in the observer, makes all the difference between the art of Intellect, and of mere sensation. For every detail of this plate has a meaning, if you care to understand it. This is Poetry, sitting by the fountain of Castalia, which flows first out of a formal urn, to show that it is not artless; but the rocks of Parnassus are behind, and on the top of them—only one tree, like a mushroom with a thick stalk. You at first are inclined to say, How very absurd, to put only one tree on Parnassus! but this one tree is the Immortal Plane Tree, planted by Agamemnon, and at once connects our Poesia with the Iliad. Then, this is the hem of the robe of Poetry,—this is the divine vegetation which springs up under her feet,—this is the heaven and earth united by her power,—this is the fountain of Castalia flowing out afresh among the grass,—and these are the drops with which, out of a pitcher, Poetry is nourishing the fountain of Castalia.

All which you may find out if you happen to know anything about Castalia, or about poetry; and pleasantly think more upon, for yourself. But the poor dunces, Sandro and Baccio, feeling themselves but 'goffi nell' arte,' have no hope of telling you all this, except suggestively. They can't engrave grass of Parnassus, nor sweet springs so as to look like water; but they can make a pretty damasked surface with ornamental leaves, and flowing lines, and so leave you something to think of—if you will.