полная версия

полная версияAriadne Florentina: Six Lectures on Wood and Metal Engraving

70. Of the security of incision as a means of permanent decoration, as opposed to ordinary carving, here is a beautiful instance in the base of one of the external shafts of the Cathedral of Lucca; thirteenth-century work, which by this time, had it been carved in relief, would have been a shapeless remnant of indecipherable bosses. But it is still as safe as if it had been cut yesterday, because the smooth round mass of the pillar is entirely undisturbed; into that, furrows are cut with a chisel as much under command and as powerful as a burin. The effect of the design is trusted entirely to the depth of these incisions—here dying out and expiring in the light of the marble, there deepened, by drill holes, into as definitely a black line as if it were drawn with ink; and describing the outline of the leafage with a delicacy of touch and of perception which no man will ever surpass, and which very few have rivaled, in the proudest days of design.

71. This security, in silver plates, was completed by filling the furrows with the black paste which at once exhibited and preserved them. The transition from that niello-work to modern engraving is one of no real moment: my object is to make you understand the qualities which constitute the merit of the engraving, whether charged with niello or ink. And this I hope ultimately to accomplish by studying with you some of the works of the four men, Botticelli and Mantegna in the south, Dürer and Holbein in the north, whose names I have put in our last flag, above and beneath those of the three mighty painters, Perugino the captain, Bellini on one side—Luini on the other.

The four following lectures16 will contain data necessary for such study: you must wait longer before I can place before you those by which I can justify what must greatly surprise some of my audience—my having given Perugino the captain's place among the three painters.

72. But I do so, at least primarily, because what is commonly thought affected in his design is indeed the true remains of the great architectural symmetry which was soon to be lost, and which makes him the true follower of Arnolfo and Brunelleschi; and because he is a sound craftsman and workman to the very heart's core. A noble, gracious, and quiet laborer from youth to death,—never weary, never impatient, never untender, never untrue. Not Tintoret in power, not Raphael in flexibility, not Holbein in veracity, not Luini in love,—their gathered gifts he has, in balanced and fruitful measure, fit to be the guide, and impulse, and father of all.

LECTURE III

THE TECHNICS OF WOOD ENGRAVING73. I am to-day to begin to tell you what it is necessary you should observe respecting methods of manual execution in the two great arts of engraving. Only to begin to tell you. There need be no end of telling you such things, if you care to hear them. The theory of art is soon mastered; but 'dal detto al fatto, v'e gran tratto;' and as I have several times told you in former lectures, every day shows me more and more the importance of the Hand.

74. Of the hand as a Servant, observe,—not of the hand as a Master. For there are two great kinds of manual work: one in which the hand is continually receiving and obeying orders; the other in which it is acting independently, or even giving orders of its own. And the dependent and submissive hand is a noble hand; but the independent or imperative hand is a vile one.

That is to say, as long as the pen, or chisel, or other graphic instrument, is moved under the direct influence of mental attention, and obeys orders of the brain, it is working nobly;—the moment it moves independently of them, and performs some habitual dexterity of its own, it is base.

75. Dexterity—I say;—some 'right-handedness' of its own. We might wisely keep that word for what the hand does at the mind's bidding; and use an opposite word—sinisterity,—for what it does at its own. For indeed we want such a word in speaking of modern art; it is all full of sinisterity. Hands independent of brains;—the left hand, by division of labor, not knowing what the right does,—still less what it ought to do.

76. Turning, then, to our special subject. All engraving, I said, is intaglio in the solid. But the solid, in wood engraving, is a coarse substance, easily cut; and in metal, a fine substance, not easily. Therefore, in general, you may be prepared to accept ruder and more elementary work in one than the other; and it will be the means of appeal to blunter minds.

You probably already know the difference between the actual methods of producing a printed impression from wood and metal; but I may perhaps make the matter a little more clear. In metal engraving, you cut ditches, fill them with ink, and press your paper into them. In wood engraving, you leave ridges, rub the tops of them with ink, and stamp them on your paper.

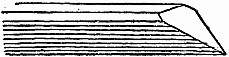

The instrument with which the substance, whether of the wood or steel, is cut away, is the same. It is a solid plowshare, which, instead of throwing the earth aside, throws it up and out, producing at first a simple ravine, or furrow, in the wood or metal, which you can widen by another cut, or extend by successive cuts. This (Fig. 1) is the general shape of the solid plowshare: but it is of course made sharper or blunter at pleasure. The furrow produced is at first the wedge-shaped or cuneiform ravine, already so much dwelt upon in my lectures on Greek sculpture.

Fig. 1

77. Since, then, in wood printing, you print from the surface left solid; and, in metal printing, from the hollows cut into it, it follows that if you put few touches on wood, you draw, as on a slate, with white lines, leaving a quantity of black; but if you put few touches on metal, you draw with black lines, leaving a quantity of white.

Now the eye is not in the least offended by quantity of white, but is, or ought to be, greatly saddened and offended by quantity of black. Hence it follows that you must never put little work on wood. You must not sketch upon it. You may sketch on metal as much as you please.

78. "Paradox," you will say, as usual. "Are not all our journals,—and the best of them, Punch, par excellence,—full of the most brilliantly swift and slight sketches, engraved on wood; while line-engravings take ten years to produce, and cost ten guineas each when they are done?"

Yes, that is so; but observe, in the first place, what appears to you a sketch on wood is not so at all, but a most laborious and careful imitation of a sketch on paper; whereas when you see what appears to be a sketch on metal, it is one. And in the second place, so far as the popular fashion is contrary to this natural method,—so far as we do in reality try to produce effects of sketching in wood, and of finish in metal,—our work is wrong.

Those apparently careless and free sketches on the wood ought to have been stern and deliberate; those exquisitely toned and finished engravings on metal ought to have looked, instead, like free ink sketches on white paper. That is the theorem which I propose to you for consideration, and which, in the two branches of its assertion, I hope to prove to you; the first part of it, (that wood-cutting should be careful,) in this present lecture; the second, (that metal-cutting should be, at least in a far greater degree than it is now, slight, and free,) in the following one.

79. Next, observe the distinction in respect of thickness, no less than number, of lines which may properly be used in the two methods.

In metal engraving, it is easier to lay a fine line than a thick one; and however fine the line may be, it lasts;—but in wood engraving it requires extreme precision and skill to leave a thin dark line, and when left, it will be quickly beaten down by a careless printer. Therefore, the virtue of wood engraving is to exhibit the qualities and power of thick lines; and of metal engraving, to exhibit the qualities and power of thin ones.

All thin dark lines, therefore, in wood, broadly speaking, are to be used only in case of necessity; and thick lines, on metal, only in case of necessity.

80. Though, however, thin dark lines cannot easily be produced in wood, thin light ones may be struck in an instant. Nevertheless, even thin light ones must not be used, except with extreme caution. For observe, they are equally useless as outline, and for expression of mass. You know how far from exemplary or delightful your boy's first quite voluntary exercises in white line drawing on your slate were? You could, indeed, draw a goblin satisfactorily in such method;—a round O, with arms and legs to it, and a scratch under two dots in the middle, would answer the purpose; but if you wanted to draw a pretty face, you took pencil or pen, and paper—not your slate. Now, that instinctive feeling that a white outline is wrong, is deeply founded. For Nature herself draws with diffused light, and concentrated dark;—never, except in storm or twilight, with diffused dark, and concentrated light; and the thing we all like best to see drawn—the human face—cannot be drawn with white touches, but by extreme labor. For the pupil and iris of the eye, the eyebrow, the nostril, and the lip are all set in dark on pale ground. You can't draw a white eyebrow, a white pupil of the eye, a white nostril, and a white mouth, on a dark ground. Try it, and see what a specter you get. But the same number of dark touches, skillfully applied, will give the idea of a beautiful face. And what is true of the subtlest subject you have to represent, is equally true of inferior ones. Nothing lovely can be quickly represented by white touches. You must hew out, if your means are so restricted, the form by sheer labor; and that both cunning and dextrous. The Florentine masters, and Dürer, often practice the achievement, and there are many drawings by the Lippis, Mantegna, and other leading Italian draughtsmen, completed to great perfection with the white line; but only for the sake of severest study, nor is their work imitable by inferior men. And such studies, however accomplished, always mark a disposition to regard chiaroscuro too much, and local color too little.

We conclude, then, that we must never trust, in wood, to our power of outline with white; and our general laws, thus far determined, will be—thick lines in wood; thin ones in metal; complete drawing on wood; sketches, if we choose, on metal.

81. But why, in wood, lines at all? Why not cut out white spaces, and use the chisel as if its incisions were so much white paint? Many fine pieces of wood-cutting are indeed executed on this principle. Bewick does nearly all his foliage so; and continually paints the light plumes of his birds with single touches of his chisel, as if he were laying on white.

But this is not the finest method of wood-cutting. It implies the idea of a system of light and shade in which the shadow is totally black. Now, no light and shade can be good, much less pleasant, in which all the shade is stark black. Therefore the finest wood-cutting ignores light and shade, and expresses only form, and dark local color. And it is convenient, for simplicity's sake, to anticipate what I should otherwise defer telling you until next lecture, that fine metal engraving, like fine wood-cutting, ignores light and shade; and that, in a word, all good engraving whatsoever does so.

82. I hope that my saying so will make you eager to interrupt me. 'What! Rembrandt's etchings, and Lupton's mezzotints, and Le Keux's line-work,—do you mean to tell us that these ignore light and shade?'

I never said that mezzotint ignored light and shade, or ought to do so. Mezzotint is properly to be considered as chiaroscuro drawing on metal. But I do mean to tell you that both Rembrandt's etchings, and Le Keux's finished line-work, are misapplied labor, in so far as they regard chiaroscuro; and that consummate engraving never uses it as a primal element of pleasure.

THE LAST FURROW.

(Fig. 2) Facsimile from Holbein's woodcut.

83. We have now got our principles so far defined that I can proceed to illustration of them by example.

Here are facsimiles, very marvelous ones,17 of two of the best wood engravings ever produced by art,—two subjects in Holbein's Dance of Death. You will probably like best that I should at once proceed to verify my last and most startling statement, that fine engraving disdained chiaroscuro.

This vignette (Fig. 2) represents a sunset in the open mountainous fields of southern Germany. And Holbein is so entirely careless about the light and shade, which a Dutchman would first have thought of, as resulting from the sunset, that, as he works, he forgets altogether where his light comes from. Here, actually, the shadow of the figure is cast from the side, right across the picture, while the sun is in front. And there is not the slightest attempt to indicate gradation of light in the sky, darkness in the forest, or any other positive element of chiaroscuro.

This is not because Holbein cannot give chiaroscuro if he chooses. He is twenty times a stronger master of it than Rembrandt; but he, therefore, knows exactly when and how to use it; and that wood engraving is not the proper means for it. The quantity of it which is needful for his story, and will not, by any sensational violence, either divert, or vulgarly enforce, the attention, he will give; and that with an unrivaled subtlety. Therefore I must ask you for a moment or two to quit the subject of technics, and look what these two woodcuts mean.

84. The one I have first shown you is of a plowman plowing at evening. It is Holbein's object, here, to express the diffused and intense light of a golden summer sunset, so far as is consistent with grander purposes. A modern French or English chiaroscurist would have covered his sky with fleecy clouds, and relieved the plowman's hat and his horses against it in strong black, and put sparkling touches on the furrows and grass. Holbein scornfully casts all such tricks aside; and draws the whole scene in pure white, with simple outlines.

THE TWO PREACHERS.

(Fig. 3) Facsimile from Holbein's woodcut.

85. And yet, when I put it beside this second vignette, (Fig. 3,) which is of a preacher preaching in a feebly lighted church, you will feel that the diffused warmth of the one subject, and diffused twilight in the other, are complete; and they will finally be to you more impressive than if they had been wrought out with every superficial means of effect, on each block.

For it is as a symbol, not as a scenic effect, that in each case the chiaroscuro is given. Holbein, I said, is at the head of the painter-reformers, and his Dance of Death is the most energetic and telling of all the forms given, in this epoch, to the Rationalist spirit of reform, preaching the new Gospel of Death,—"It is no matter whether you are priest or layman, what you believe, or what you do: here is the end." You shall see, in the course of our inquiry, that Botticelli, in like manner, represents the Faithful and Catholic temper of reform.

86. The teaching of Holbein is therefore always melancholy,—for the most part purely rational; and entirely furious in its indignation against all who, either by actual injustice in this life, or by what he holds to be false promise of another, destroy the good, or the energy, of the few days which man has to live. Against the rich, the luxurious, the Pharisee, the false lawyer, the priest, and the unjust judge, Holbein uses his fiercest mockery; but he is never himself unjust; never caricatures or equivocates; gives the facts as he knows them, with explanatory symbols, few and clear.

87. Among the powers which he hates, the pathetic and ingenious preaching of untruth is one of the chief; and it is curious to find his biographer, knowing this, and reasoning, as German critics nearly always do, from acquired knowledge, not perception, imagine instantly that he sees hypocrisy in the face of Holbein's preacher. "How skillfully," says Dr. Woltmann, "is the preacher propounding his doctrines; how thoroughly is his hypocrisy expressed in the features of his countenance, and in the gestures of his hands." But look at the cut yourself, candidly. I challenge you to find the slightest trace of hypocrisy in either feature or gesture. Holbein knew better. It is not the hypocrite who has power in the pulpit. It is the sincere preacher of untruth who does mischief there. The hypocrite's place of power is in trade, or in general society; none but the sincere ever get fatal influence in the pulpit. This man is a refined gentleman—ascetic, earnest, thoughtful, and kind. He scarcely uses the vantage even of his pulpit,—comes aside out of it, as an eager man would, pleading; he is intent on being understood—is understood; his congregation are delighted—you might hear a pin drop among them: one is asleep indeed, who cannot see him, (being under the pulpit,) and asleep just because the teacher is as gentle as he is earnest, and speaks quietly.

88. How are we to know, then, that he speaks in vain? First, because among all his hearers you will not find one shrewd face. They are all either simple or stupid people: there is one nice woman in front of all, (else Holbein's representation had been caricature,) but she is not a shrewd one.

Secondly, by the light and shade. The church is not in extreme darkness—far from that; a gray twilight is over everything, but the sun is totally shut out of it;—not a ray comes in even at the window—that is darker than the walls, or vault.

Lastly, and chiefly, by the mocking expression of Death. Mocking, but not angry. The man has been preaching what he thought true. Death laughs at him, but is not indignant with him.

Death comes quietly: I am going to be preacher now; here is your own hour-glass, ready for me. You have spoken many words in your day. But "of the things which you have spoken, this is the sum,"—your death-warrant, signed and sealed. There's your text for to-day.

89. Of this other picture, the meaning is more plain, and far more beautiful. The husbandman is old and gaunt, and has passed his days, not in speaking, but pressing the iron into the ground. And the payment for his life's work is, that he is clothed in rags, and his feet are bare on the clods; and he has no hat—but the brim of a hat only, and his long, unkempt gray hair comes through. But all the air is full of warmth and of peace; and, beyond his village church, there is, at last, light indeed. His horses lag in the furrow, and his own limbs totter and fail: but one comes to help him. 'It is a long field,' says Death; 'but we'll get to the end of it to-day,—you and I.'

90. And now that we know the meaning, we are able to discuss the technical qualities farther.

Both of these engravings, you will find, are executed with blunt lines; but more than that, they are executed with quiet lines, entirely steady.

Now, here I have in my hand a lively woodcut of the present day—a good average type of the modern style of wood-cutting, which you will all recognize.18

The shade in this is drawn on the wood, (not cut, but drawn, observe,) at the rate of at least ten lines in a second: Holbein's, at the rate of about one line in three seconds.19

91. Now there are two different matters to be considered with respect to these two opposed methods of execution. The first, that the rapid work, though easy to the artist, is very difficult to the wood-cutter; so that it implies instantly a separation between the two crafts, and that your wood-cutter has ceased to be a draughtsman. I shall return to this point. I wish to insist on the other first; namely, the effect of the more deliberate method on the drawing itself.

92. When the hand moves at the rate of ten lines in a second, it is indeed under the government of the muscles of the wrist and shoulder; but it cannot possibly be under the complete government of the brains. I am able to do this zigzag line evenly, because I have got the use of the hand from practice; and the faster it is done, the evener it will be. But I have no mental authority over every line I thus lay: chance regulates them. Whereas, when I draw at the rate of two or three seconds to each line, my hand disobeys the muscles a little—the mechanical accuracy is not so great; nay, there ceases to be any appearance of dexterity at all. But there is, in reality, more manual skill required in the slow work than in the swift,—and all the while the hand is thoroughly under the orders of the brains. Holbein deliberately resolves, for every line, as it goes along, that it shall be so thick, so far from the next,—that it shall begin here, and stop there. And he is deliberately assigning the utmost quantity of meaning to it, that a line will carry.

93. It is not fair, however, to compare common work of one age with the best of another. Here is a woodcut of Tenniel's, which I think contains as high qualities as it is possible to find in modern art.20 I hold it as beyond others fine, because there is not the slightest caricature in it. No face, no attitude, is pushed beyond the degree of natural humor they would have possessed in life; and in precision of momentary expression, the drawing is equal to the art of any time, and shows power which would, if regulated, be quite adequate to producing an immortal work.

94. Why, then, is it not immortal? You yourselves, in compliance with whose demand it was done, forgot it the next week. It will become historically interesting; but no man of true knowledge and feeling will ever keep this in his cabinet of treasure, as he does these woodcuts of Holbein's.

The reason is that this is base coin,—alloyed gold. There is gold in it, but also a quantity of brass and lead—willfully added—to make it fit for the public. Holbein's is beaten gold, seven times tried in the fire. Of which commonplace but useful metaphor the meaning here is, first, that to catch the vulgar eye a quantity of,—so-called,—light and shade is added by Tenniel. It is effective to an ignorant eye, and is ingeniously disposed; but it is entirely conventional and false, unendurable by any person who knows what chiaroscuro is.

Secondly, for one line that Holbein lays, Tenniel has a dozen. There are, for instance, a hundred and fifty-seven lines in Sir Peter Teazle's wig, without counting dots and slight cross-hatching;—but the entire face and flowing hair of Holbein's preacher are done with forty-five lines, all told.

95. Now observe what a different state of mind the two artists must be in on such conditions;—one, never in a hurry, never doing anything that he knows is wrong; never doing a line badly that he can do better; and appealing only to the feelings of sensitive persons, and the judgment of attentive ones. That is Holbein's habit of soul. What is the habit of soul of every modern engraver? Always in a hurry; everywhere doing things which he knows to be wrong—(Tenniel knows his light and shade to be wrong as well as I do)—continually doing things badly which he was able to do better; and appealing exclusively to the feelings of the dull, and the judgment of the inattentive.

Do you suppose that is not enough to make the difference between mortal and immortal art,—the original genius being supposed alike in both?21

96. Thus far of the state of the artist himself. I pass, next to the relation between him and his subordinate, the wood-cutter.

The modern artist requires him to cut a hundred and fifty-seven lines in the wig only,—the old artist requires him to cut forty-five for the face, and long hair, altogether. The actual proportion is roughly, and on the average, about one to twenty of cost in manual labor, ancient to modern,—the twentieth part of the mechanical labor, to produce an immortal instead of a perishable work,—the twentieth part of the labor; and—which is the greatest difference of all—that twentieth part, at once less mechanically difficult, and more mentally pleasant. Mr. Otley, in his general History of Engraving, says, "The greatest difficulty in wood engraving occurs in clearing out the minute quadrangular lights;" and in any modern woodcut you will see that where the lines of the drawing cross each other to produce shade, the white interstices are cut out so neatly that there is no appearance of any jag or break in the lines; they look exactly as if they had been drawn with a pen. It is chiefly difficult to cut the pieces clearly out when the lines cross at right angles; easier when they form oblique or diamond-shaped interstices; but in any case some half-dozen cuts, and in square crossings as many as twenty, are required to clear one interstice. Therefore if I carelessly draw six strokes with my pen across other six, I produce twenty-five interstices, each of which will need at least six, perhaps twenty, careful touches of the burin to clear out.—Say ten for an average; and I demand two hundred and fifty exquisitely precise touches from my engraver, to render ten careless ones of mine.