полная версия

полная версияAriadne Florentina: Six Lectures on Wood and Metal Engraving

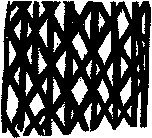

97. Now I take up Punch, at his best. The whole of the left side of John Bull's waistcoat—the shadow on his knee-breeches and great-coat—the whole of the Lord Chancellor's gown, and of John Bull's and Sir Peter Teazle's complexions, are worked with finished precision of cross-hatching. These have indeed some purpose in their texture; but in the most wanton and gratuitous way, the wall below the window is cross-hatched too, and that not with a double, but a treble line (Fig. 4).

There are about thirty of these columns, with thirty-five interstices each: approximately, 1,050—certainly not fewer—interstices to be deliberately cut clear, to get that two inches square of shadow. Now calculate—or think enough to feel the impossibility of calculating—the number of woodcuts used daily for our popular prints, and how many men are night and day cutting 1,050 square holes to the square inch, as the occupation of their manly life. And Mrs. Beecher Stowe and the North Americans fancy they have abolished slavery!

Fig. 4.

98. The workman cannot have even the consolation of pride; for his task, even in its finest accomplishment, is not really difficult,—only tedious. When you have once got into the practice, it is as easy as lying. To cut regular holes without a purpose is easy enough; but to cut irregular holes with a purpose, that is difficult, forever;—no tricks of tool or trade will give you power to do that.

The supposed difficulty—the thing which, at all events, it takes time to learn, is to cut the interstices neat, and each like the other. But is there any reason, do you suppose, for their being neat, and each like the other? So far from it, they would be twenty times prettier if they were irregular, and each different from the other. And an old wood-cutter, instead of taking pride in cutting these interstices smooth and alike, resolutely cuts them rough and irregular; taking care, at the same time, never to have any more than are wanted, this being only one part of the general system of intelligent manipulation, which made so good an artist of the engraver that it is impossible to say of any standard old woodcut, whether the draughtsman engraved it himself or not. I should imagine, from the character and subtlety of the touch, that every line of the Dance of Death had been engraved by Holbein; we know it was not, and that there can be no certainty given by even the finest pieces of wood execution of anything more than perfect harmony between the designer and workman. And consider how much this harmony demands in the latter. Not that the modern engraver is unintelligent in applying his mechanical skill: very often he greatly improves the drawing; but we never could mistake his hand for Holbein's.

99. The true merit, then, of wood execution, as regards this matter of cross-hatching, is first that there be no more crossing than necessary; secondly, that all the interstices be various, and rough. You may look through the entire series of the Dance of Death without finding any cross-hatching whatever, except in a few unimportant bits of background, so rude as to need scarcely more than one touch to each interstice. Albert Dürer crosses more definitely; but yet, in any fold of his drapery, every white spot differs in size from every other, and the arrangement of the whole is delightful, by the kind of variety which the spots on a leopard have.

On the other hand, where either expression or form can be rendered by the shape of the lights and darks, the old engraver becomes as careful as in an ordinary ground he is careless.

The endeavor, with your own hand, and common pen and ink, to copy a small piece of either of the two Holbein woodcuts (Figures 2 and 3) will prove this to you better than any words.

100. I said that, had Tenniel been rightly trained, there might have been the making of a Holbein, or nearly a Holbein, in him. I do not know; but I can turn from his work to that of a man who was not trained at all, and who was, without training, Holbein's equal.

Equal, in the sense that this brown stone, in my left hand, is the equal, though not the likeness, of that in my right. They are both of the same true and pure crystal; but the one is brown with iron, and never touched by forming hand; the other has never been in rough companionship, and has been exquisitely polished. So with these two men. The one was the companion of Erasmus and Sir Thomas More. His father was so good an artist that you cannot always tell their drawings asunder. But the other was a farmer's son; and learned his trade in the back shops of Newcastle.

Yet the first book I asked you to get was his biography; and in this frame are set together a drawing by Hans Holbein, and one by Thomas Bewick. I know which is most scholarly; but I do not know which is best.

101. It is much to say for the self-taught Englishman;—yet do not congratulate yourselves on his simplicity. I told you, a little while since, that the English nobles had left the history of birds to be written, and their spots to be drawn, by a printer's lad;—but I did not tell you their farther loss in the fact that this printer's lad could have written their own histories, and drawn their own spots, if they had let him. But they had no history to be written; and were too closely maculate to be portrayed;—white ground in most places altogether obscured. Had there been Mores and Henrys to draw, Bewick could have drawn them; and would have found his function. As it was, the nobles of his day left him to draw the frogs, and pigs, and sparrows—of his day, which seemed to him, in his solitude, the best types of its Nobility. No sight or thought of beautiful things was ever granted him;—no heroic creature, goddess-born—how much less any native Deity—ever shone upon him. To his utterly English mind, the straw of the sty, and its tenantry, were abiding truth;—the cloud of Olympus, and its tenantry, a child's dream. He could draw a pig, but not an Aphrodite.

102. The three pieces of woodcut from his Fables (the two lower ones enlarged) in the opposite plate, show his utmost strength and utmost rudeness. I must endeavor to make you thoroughly understand both:—the magnificent artistic power, the flawless virtue, veracity, tenderness,—the infinite humor of the man; and yet the difference between England and Florence, in the use they make of such gifts in their children.

For the moment, however, I confine myself to the examination of technical points; and we must follow our former conclusions a little further.

I.

Things Celestial and Terrestrial, as apparent to the English Mind.

103. Because our lines in wood must be thick, it becomes an extreme virtue in wood engraving to economize lines,—not merely, as in all other art, to save time and power, but because, our lines being necessarily blunt, we must make up our minds to do with fewer, by many, than are in the object. But is this necessarily a disadvantage?

Absolutely, an immense disadvantage,—a woodcut never can be so beautiful or good a thing as a painting, or line engraving. But in its own separate and useful way, an excellent thing, because, practiced rightly, it exercises in the artist, and summons in you, the habit of abstraction; that is to say, of deciding what are the essential points in the things you see, and seizing these; a habit entirely necessary to strong humanity; and so natural to all humanity, that it leads, in its indolent and undisciplined states, to all the vulgar amateur's liking of sketches better than pictures. The sketch seems to put the thing for him into a concentrated and exciting form.

104. Observe, therefore, to guard you from this error, that a bad sketch is good for nothing; and that nobody can make a good sketch unless they generally are trying to finish with extreme care. But the abstraction of the essential particulars in his subject by a line-master, has a peculiar didactic value. For painting, when it is complete, leaves it much to your own judgment what to look at; and, if you are a fool, you look at the wrong thing;—but in a fine woodcut, the master says to you, "You shall look at this, or at nothing."

105. For example, here is a little tailpiece of Bewick's, to the fable of the Frogs and the Stork.22 He is, as I told you, as stout a reformer as Holbein,23 or Botticelli, or Luther, or Savonarola; and, as an impartial reformer, hits right and left, at lower or upper classes, if he sees them wrong. Most frequently, he strikes at vice, without reference to class; but in this vignette he strikes definitely at the degradation of the viler popular mind which is incapable of being governed, because it cannot understand the nobleness of kingship. He has written—better than written, engraved, sure to suffer no slip of type—his legend under the drawing; so that we know his meaning:

"Set them up with a king, indeed!"

106. There is an audience of seven frogs, listening to a speaker, or croaker, in the middle; and Bewick has set himself to show in all, but especially in the speaker, essential frogginess of mind—the marsh temper. He could not have done it half so well in painting as he has done by the abstraction of wood-outline. The characteristic of a manly mind, or body, is to be gentle in temper, and firm in constitution; the contrary essence of a froggy mind and body is to be angular in temper, and flabby in constitution. I have enlarged Bewick's orator-frog for you, Plate I. c., and I think you will feel that he is entirely expressed in those essential particulars.

This being perfectly good wood-cutting, notice especially its deliberation. No scrawling or scratching, or cross-hatching, or 'free' work of any sort. Most deliberate laying down of solid lines and dots, of which you cannot change one. The real difficulty of wood engraving is to cut every one of these black lines or spaces of the exactly right shape, and not at all to cross-hatch them cleanly.

107. Next, examine the technical treatment of the pig, above. I have purposely chosen this as an example of a white object on dark ground, and the frog as a dark object on light ground, to explain to you what I mean by saying that fine engraving regards local color, but not light and shade. You see both frog and pig are absolutely without light and shade. The frog, indeed, casts a shadow; but his hind leg is as white as his throat. In the pig you don't even know which way the light falls. But you know at once that the pig is white, and the frog brown or green.

108. There are, however, two pieces of chiaroscuro implied in the treatment of the pig. It is assumed that his curly tail would be light against the background—dark against his own rump. This little piece of heraldic quartering is absolutely necessary to solidify him. He would have been a white ghost of a pig, flat on the background, but for that alternative tail, and the bits of dark behind the ears. Secondly: Where the shade is necessary to suggest the position of his ribs, it is given with graphic and chosen points of dark, as few as possible; not for the sake of the shade at all, but of the skin and bone.

109. That, then, being the law of refused chiaroscuro, observe further the method of outline. We said that we were to have thick lines in wood, if possible. Look what thickness of black outline Bewick has left under our pig's chin, and above his nose.

But that is not a line at all, you think?

No;—a modern engraver would have made it one, and prided himself on getting it fine. Bewick leaves it actually thicker than the snout, but puts all his ingenuity of touch to vary the forms, and break the extremities of his white cuts, so that the eye may be refreshed and relieved by new forms at every turn. The group of white touches filling the space between snout and ears might be a wreath of fine-weather clouds, so studiously are they grouped and broken.

And nowhere, you see, does a single black line cross another.

Look back to Figure 4, page 54, and you will know, henceforward, the difference between good and bad wood-cutting.

110. We have also, in the lower woodcut, a notable instance of Bewick's power of abstraction. You will observe that one of the chief characters of this frog, which makes him humorous,—next to his vain endeavor to get some firmness into his fore feet,—is his obstinately angular hump-back. And you must feel, when you see it so marked, how important a general character of a frog it is to have a hump-back,—not at the shoulders, but the loins.

111. Here, then, is a case in which you will see the exact function that anatomy should take in art.

All the most scientific anatomy in the world would never have taught Bewick, much less you, how to draw a frog.

But when once you have drawn him, or looked at him, so as to know his points, it then becomes entirely interesting to find out why he has a hump-back. So I went myself yesterday to Professor Rolleston for a little anatomy, just as I should have gone to Professor Phillips for a little geology; and the Professor brought me a fine little active frog; and we put him on the table, and made him jump all over it, and then the Professor brought in a charming Squelette of a frog, and showed me that he needed a projecting bone from his rump, as a bird needs it from its breast,—the one to attach the strong muscles of the hind legs, as the other to attach those of the fore legs or wings. So that the entire leaping power of the frog is in his hump-back, as the flying power of the bird is in its breast-bone. And thus this Frog Parliament is most literally a Rump Parliament—everything depending on the hind legs, and nothing on the brains; which makes it wonderfully like some other Parliaments we know of nowadays, with Mr. Ayrton and Mr. Lowe for their æsthetic and acquisitive eyes, and a rump of Railway Directors.

112. Now, to conclude, for want of time only—I have but touched on the beginning of my subject,—understand clearly and finally this simple principle of all art, that the best is that which realizes absolutely, if possible. Here is a viper by Carpaccio: you are afraid to go near it. Here is an arm-chair by Carpaccio: you who came in late, and are standing, to my regret, would like to sit down in it. This is consummate art; but you can only have that with consummate means, and exquisitely trained and hereditary mental power.

With inferior means, and average mental power, you must be content to give a rude abstraction; but if rude abstraction is to be made, think what a difference there must be between a wise man's and a fool's; and consider what heavy responsibility lies upon you in your youth, to determine, among realities, by what you will be delighted, and, among imaginations, by whose you will be led.

LECTURE IV

THE TECHNICS OF METAL ENGRAVING113. We are to-day to examine the proper methods for the technical management of the most perfect of the arms of precision possessed by the artist. For you will at once understand that a line cut by a finely-pointed instrument upon the smooth surface of metal is susceptible of the utmost fineness that can be given to the definite work of the human hand. In drawing with pen upon paper, the surface of the paper is slightly rough; necessarily, two points touch it instead of one, and the liquid flows from them more or less irregularly, whatever the draughtsman's skill. But you cut a metallic surface with one edge only; the furrow drawn by a skater on the surface of ice is like it on a large scale. Your surface is polished, and your line may be wholly faultless, if your hand is.

114. And because, in such material, effects may be produced which no penmanship could rival, most people, I fancy, think that a steel plate half engraves itself; that the workman has no trouble with it, compared to that of a pen draughtsman.

To test your feeling in this matter accurately, here is a manuscript book written with pen and ink, and illustrated with flourishes and vignettes.

You will all, I think, be disposed, on examining it, to exclaim, How wonderful! and even to doubt the possibility of every page in the book being completed in the same manner. Again, here are three of my own drawings, executed with the pen, and Indian ink, when I was fifteen. They are copies from large lithographs by Prout; and I imagine that most of my pupils would think me very tyrannical if I requested them to do anything of the kind themselves. And yet, when you see in the shop windows a line engraving like this,1 or this,1either of which contains, alone, as much work as fifty pages of the manuscript book, or fifty such drawings as mine, you look upon its effect as quite a matter of course,—you never say 'how wonderful' that is, nor consider how you would like to have to live, by producing anything of the same kind yourselves.

II.

The Star of FLORENCE.

115. Yet you cannot suppose it is in reality easier to draw a line with a cutting point, not seeing the effect at all, or, if any effect, seeing a gleam of light instead of darkness, than to draw your black line at once on the white paper? You cannot really think24 that there is something complacent, sympathetic, and helpful in the nature of steel; so that while a pen-and-ink sketch may always be considered an achievement proving cleverness in the sketcher, a sketch on steel comes out by mere favor of the indulgent metal; or that the plate is woven like a piece of pattern silk, and the pattern is developed by pasteboard cards punched full of holes? Not so. Look close at this engraving, or take a smaller and simpler one, Turner's Mercury and Argus,—imagine it to be a drawing in pen and ink, and yourself required similarly to produce its parallel! True, the steel point has the one advantage of not blotting, but it has tenfold or twentyfold disadvantage, in that you cannot slur, nor efface, except in a very resolute and laborious way, nor play with it, nor even see what you are doing with it at the moment, far less the effect that is to be. You must feel what you are doing with it, and know precisely what you have got to do; how deep, how broad, how far apart your lines must be, etc. and etc., (a couple of lines of etceteras would not be enough to imply all you must know). But suppose the plate were only a pen drawing: take your pen—your finest—and just try to copy the leaves that entangle the head of Io, and her head itself; remembering always that the kind of work required here is mere child's play compared to that of fine figure engraving. Nevertheless, take a small magnifying glass to this—count the dots and lines that gradate the nostrils and the edges of the facial bone; notice how the light is left on the top of the head by the stopping, at its outline, of the coarse touches which form the shadows under the leaves; examine it well, and then—I humbly ask of you—try to do a piece of it yourself! You clever sketcher—you young lady or gentleman of genius—you eye-glassed dilettante—you current writer of criticism royally plural,—I beseech you,—do it yourself; do the merely etched outline yourself, if no more. Look you,—you hold your etching needle this way, as you would a pencil, nearly; and then,—you scratch with it! it is as easy as lying. Or if you think that too difficult, take an easier piece;—take either of the light sprays of foliage that rise against the fortress on the right, pass your lens over them—look how their fine outline is first drawn, leaf by leaf; then how the distant rock is put in between, with broken lines, mostly stopping before they touch the leaf-outline; and again, I pray you, do it yourself,—if not on that scale, on a larger. Go on into the hollows of the distant rock,—traverse its thickets,—number its towers;—count how many lines there are in a laurel bush—in an arch—in a casement; some hundred and fifty, or two hundred, deliberately drawn lines, you will find, in every square quarter of an inch;—say three thousand to the inch,—each, with skillful intent, put in its place! and then consider what the ordinary sketcher's work must appear, to the men who have been trained to this!

116. "But might not more have been done by three thousand lines to a square inch?" you will perhaps ask. Well, possibly. It may be with lines as with soldiers: three hundred, knowing their work thoroughly, may be stronger than three thousand less sure of their aim. We shall have to press close home this question about numbers and purpose presently;—it is not the question now. Suppose certain results required,—atmospheric effects, surface textures, transparencies of shade, confusions of light,—then, more could not be done with less. There are engravings of this modern school, of which, with respect to their particular aim, it may be said, most truly, they "cannot be better done."

Here is one just finished,—or, at least, finished to the eyes of ordinary mortals, though its fastidious master means to retouch it;—a quite pure line engraving, by Mr. Charles Henry Jeens; (in calling it pure line, I mean that there are no mixtures of mezzotint or any mechanical tooling, but all is steady hand-work,) from a picture by Mr. Armytage, which, without possessing any of the highest claims to admiration, is yet free from the vulgar vices which disgrace most of our popular religious art; and is so sweet in the fancy of it as to deserve, better than many works of higher power, the pains of the engraver to make it a common possession. It is meant to help us to imagine the evening of the day when the father and mother of Christ had been seeking Him through Jerusalem: they have come to a well where women are drawing water; St. Joseph passes on,—but the tired Madonna, leaning on the well's margin, asks wistfully of the women if they have seen such and such a child astray. Now will you just look for a while into the lines by which the expression of the weary and anxious face is rendered; see how unerring they are,—how calm and clear; and think how many questions have to be determined in drawing the most minute portion of any one,—its curve,—its thickness,—its distance from the next,—its own preparation for ending, invisibly, where it ends. Think what the precision must be in these that trace the edge of the lip, and make it look quivering with disappointment, or in these which have made the eyelash heavy with restrained tears.

117. Or if, as must be the case with many of my audience, it is impossible for you to conceive the difficulties here overcome, look merely at the draperies, and other varied substances represented in the plate; see how silk, and linen, and stone, and pottery, and flesh, are all separated in texture, and gradated in light, by the most subtle artifices and appliances of line,—of which artifices, and the nature of the mechanical labor throughout, I must endeavor to give you to-day a more distinct conception than you are in the habit of forming. But as I shall have to blame some of these methods in their general result, and I do not wish any word of general blame to be associated with this most excellent and careful plate by Mr. Jeens, I will pass, for special examination, to one already in your reference series, which for the rest exhibits more various treatment in its combined landscape, background, and figures; the Belle Jardinière of Raphael, drawn and engraved by the Baron Desnoyers.

You see, in the first place, that the ground, stones, and other coarse surfaces are distinguished from the flesh and draperies by broken and wriggled lines. Those broken lines cannot be executed with the burin, they are etched in the early states of the plate, and are a modern artifice, never used by old engravers; partly because the older men were not masters of the art of etching, but chiefly because even those who were acquainted with it would not employ lines of this nature. They have been developed by the importance of landscape in modern engraving, and have produced some valuable results in small plates, especially of architecture. But they are entirely erroneous in principle, for the surface of stones and leaves is not broken or jagged in this manner, but consists of mossy, or blooming, or otherwise organic texture, which cannot be represented by these coarse lines; their general consequence has therefore been to withdraw the mind of the observer from all beautiful and tender characters in foreground, and eventually to destroy the very school of landscape engraving which gave birth to them.