полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

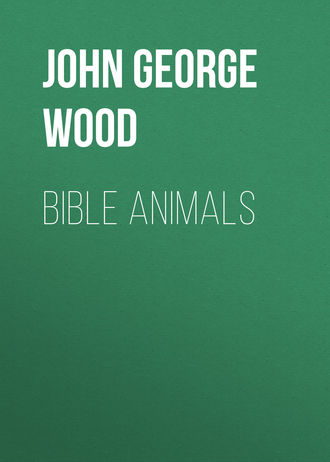

THE FROG

The Frog only mentioned in the Old Testament as connected with the plagues of Egypt—The severity of this plague explained—The Frog detestable to the Egyptians—The Edible Frog and its numbers—Description of the species.

Plentiful as is the Frog throughout Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, it is very remarkable that in the whole of the canonical books of the Old Testament the word is only mentioned thrice, and each case in connexion with the same event.

In Exod. viii. we find that the second of the plagues which visited Egypt came out of the Nile, the sacred river, in the form of innumerable Frogs. The reader will probably remark, on perusing the consecutive account of these plagues, that the two first plagues were connected with that river, and that they were foreshadowed by the transformation of Aaron's rod.

When Moses and Aaron appeared before Pharaoh to ask him to let the people go, Pharaoh demanded a miracle from them, as had been foretold. Following the divine command, Aaron threw down his rod, which was transformed into a crocodile—the most sacred inhabitant of the sacred river—a river which was to the Egyptians what the Ganges is to the Hindoos.

Next, as was most appropriate, came a transformation wrought on the river by means of the same rod which had been transformed into a crocodile, the whole of the fresh-water throughout the land being turned into blood, and the fish dying and polluting the venerated river with their putrefying bodies. In Egypt, a partially rainless country, such a calamity as this was doubly terrible, as it at the same time desecrated the object of their worship, and menaced them with perishing by thirst.

THE FROG. (Rana esculenta).

"And the river shall bring forth frogs abundantly."—Exod. viii. 3.

The next plague had also its origin in the river, but extended far beyond the limits of its banks. The frogs, being unable to return to the contaminated stream wherein they had lived, spread themselves in all directions, so as to fulfil the words of the prediction: "If thou refuse to let them go, behold, I will smite all thy borders with frogs:

"And the river shall bring forth frogs abundantly, which shall go up and come into thine house, and into thy bed-chamber, and upon thy bed, and into the house of thy servants, and upon thy people, and into thine ovens, and into thy kneading-troughs" (or dough).

Supposing that such a plague was to come upon us at the present day, we should consider it to be a terrible annoyance, yet scarcely worthy of the name of plague, and certainly not to be classed with the turning of a river into blood, with the hail and lightning that destroyed the crops and cattle, and with the simultaneous death of the first-born. But the Egyptians suffered most keenly from the infliction. They were a singularly fastidious people, and abhorred the contact of anything that they held to be unclean. We may well realize, therefore, the effect of a visitation of Frogs, which rendered their houses unclean by entering them, and themselves unclean by leaping upon them; which deprived them of rest by getting on their beds, and of food by crawling into their ovens and upon the dough in the kneading-troughs.

And, as if to make the visitation still worse, when the plague was removed, the Frogs died in the places into which they had intruded, so that the Egyptians were obliged to clear their houses of the dead carcases, and to pile them up in heaps, to be dried by the sun or eaten by birds and other scavengers of the East.

As to the species of Frog which thus invaded the houses of the Egyptians, there is no doubt whatever. It can be but the Green, or Edible Frog (Rana esculenta), which is so well known for the delicacy of its flesh. This is believed to be the only aquatic Frog of Egypt, and therefore must be the species which came out of the river into the houses.

Both in Egypt and Palestine it exists in very great numbers, swarming in every marshy place, and inhabiting the pools in such numbers that the water can scarcely be seen for the Frogs. Thus the multitudes of the Frogs which invaded the Egyptians was no matter of wonder, the only miraculous element being that the reptiles were simultaneously directed to the houses, and their simultaneous death when the plague was taken away.

It has, however, been suggested that, at the time of year at which the event occurred, the young Frogs were in the tadpole stage of existence, and therefore would not be able to pass over land. But, even granting that to be the case, it does not follow that the adult Frogs were not numerous enough to produce the visitation, and it seems likely that those who were not yet developed were left to reproduce the race after the full-grown Frogs had perished.

The Green Frog is larger than our common English species, and is prettily coloured, the back being green, spotted with black, and having three black stripes upon it. The under parts are yellowish. At night it keeps up a continued and very loud croaking, so that a pond in which a number of these Frogs are kept is quite destructive of sleep to any one who is not used to the noise.

Frogs are also mentioned in Rev. xvi. 13: "And I saw three unclean spirits like frogs come out of the mouth of the dragon, and out of the mouth of the beast, and out of the mouth of the false prophet." With the exception of this passage, which is a purely symbolical one, there is no mention of Frogs in the New Testament. It is rather remarkable that the Toad, which might be thought to afford an excellent symbol for various forms of evil, is entirely ignored, both in the Old and New Testaments. Probably the Frogs and Toads were all classed together under the same title.

FISHES

Impossibility of distinguishing the different species of Fishes—The fishermen Apostles—Fish used for food—The miracle of the loaves and Fishes—The Fish broiled on the coals—Clean and unclean Fishes—The scientific writings of Solomon—The Sheat-fish, or Silurus—The Eel and the Muræna—The Long-headed Barbel—Fish-ponds and preserves—The Fish-ponds of Heshbon—The Sucking-fish—The Lump-sucker—The Tunny—The Coryphene.

We now come to the Fishes, a class of animals which are repeatedly mentioned both in the Old and New Testaments, but only in general terms, no one species being described so as to give the slightest indication of its identity.

This is the more remarkable because, although the Jews were, like all Orientals, utterly unobservant of those characteristics by which the various species are distinguished from each other, we might expect that St. Peter and other of the fisher Apostles would have given the names of some of the Fish which they were in the habit of catching, and by the sale of which they gained their living.

It is true that the Jews, as a nation, would not distinguish between the various species of Fishes, except, perhaps, by comparative size. But professional fishermen would be sure to distinguish one species from another, if only for the fact that they would sell the best-flavoured Fish at the highest price.

We might have expected, for example, that the Apostles and disciples who were present when the miraculous draught of Fishes took place would have mentioned the technical names by which they were accustomed to distinguish the different degrees of the saleable and unsaleable kinds.

Or we might have expected that on the occasion when St. Peter cast his line and hook into the sea, and drew out a Fish holding the tribute-money in his mouth, we might have learned the particular species of Fish which was thus captured. We ourselves would assuredly have done so. It would not have been thought sufficient merely to say that a Fish was caught with money in its mouth, but it would have been considered necessary to mention the particular fish as well as the particular coin.

But it must be remembered that the whole tone of thought differs in Orientals and Europeans, and that the exactness required by the one has no place in the mind of the other. The whole of the Scriptural narratives are essentially Oriental in their character, bringing out the salient points in strong relief, but entirely regardless of minute detail.

We find from many passages both in the Old and New Testaments that Fish were largely used as food by the Israelites, both when captives in Egypt and after their arrival in the Promised Land. Take, for example, Numb. xi. 4, 5: "And the children of Israel also wept again, and said, Who shall give us flesh to eat?

"We remember the fish which we did eat in Egypt freely." Then, in the Old Testament, although we do not find many such categorical statements, there are many passages which allude to professional fishermen, showing that there was a demand for the Fish which they caught, sufficient to yield them a maintenance.

In the New Testament, however, there are several passages in which the Fishes are distinctly mentioned as articles of food. Take, for example, the well-known miracle of multiplying the loaves and the Fishes, and the scarcely less familiar passage in John xxi. 9: "As soon then as they were come to land, they saw a fire of coals there, and fish laid thereon, and bread.

"Jesus saith unto them, Bring of the fish which ye have now caught.

"Simon Peter went up, and drew the net to land full of great fishes, an hundred and fifty and three: and for all there were so many, yet was not the net broken.

"Jesus saith unto them, Come and dine. And none of the disciples durst ask Him, Who art Thou? knowing that it was the Lord.

"Jesus then cometh, and taketh bread, and giveth them, and fish likewise."

We find in all these examples that bread and Fish were eaten together. Indeed, Fish was eaten with bread just as we eat cheese or butter; and St. John, in his account of the multiplication of the loaves and Fishes, does not use the word "fish," but another word which rather signifies sauce, and was generally employed to designate the little Fish that were salted down and dried in the sunbeams for future use.

As to the various species which were used for different purposes, we know really nothing, the Jews merely dividing their Fish into clean and unclean.

Still, we find that Solomon treated of Fishes as well as of other portions of the creation. "And he spake of trees, from the cedar tree that is in Lebanon even unto the hyssop that springeth out of the wall: he spake also of beasts, and of fowl, and of creeping things, and of fishes." (1 Kings iv. 33.)

Now it is evidently impossible that Solomon could have treated of Fishes without distinguishing between their various species. Comparatively young as he was, he had received such a measure of divine inspiration, that "there came of all people to know the wisdom of Solomon, from all kings of the earth, which had heard of his wisdom."

Yet, although some of his poetical and instructive writings have survived to our time, the whole of his works on natural history have so completely perished, that they have not even introduced into the language the names of the various creatures of which he wrote. So, in spite of all his labours, there is not a single word in the Hebrew language, as now known, by which one species of Fish can be distinguished from another, as to the distinction between the clean and unclean Fishes.

According to Levit. xi. the qualification for food lay simply in the possession of fins and scales. "These shall ye eat of all that are in the waters: whatsoever hath fins and scales in the waters, in the seas, and in the rivers, them shall ye eat.

"And all that have not fins and scales in the seas, and in the rivers, of all that move in the waters, and of any living thing which is in the waters, they shall be an abomination unto you:

"They shall be even an abomination unto you; ye shall not eat of their flesh, but ye shall have their carcases in abomination" (ver. 9-11). There is a similar prohibition in Deut. xiv. 9.

Some of the species to which this prohibition would extend are evident enough. There are, for example, the Sheat-fishes, which have the body naked, and which are therefore taken out of the list of permitted Fishes. The Sheat-fishes inhabit rivers in many parts of the world, and often grow to a very considerable size. They may be at once recognised by their peculiar shape, and by the long, fleshy tentacles that hang from the mouth. The object of these tentacles is rather dubious, but as the fish have been seen to direct them at will to various objects, it is likely that they may answer as organs of touch.

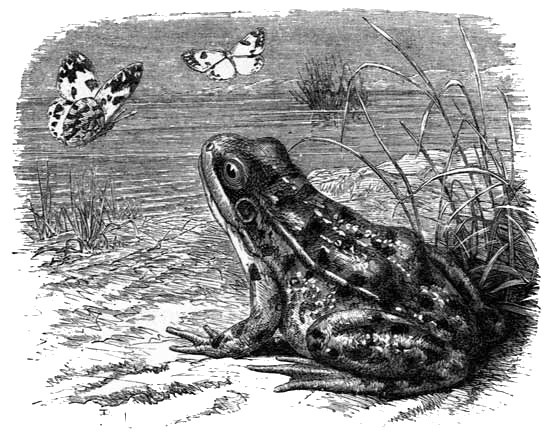

1. Muræna (Muræna helena). 2. Long-headed Barbel (Barbus longiceps).

3. Sheat-fish (Silurus macracanthus).

"All that have not fins and scales … shall be an abomination unto you."—Levit. xi. 10.

As might be conjectured from its general appearance, it is one of the Fishes that love muddy banks, in which it is fond of burrowing so deeply that, although the river may swarm with Sheat-fishes, a practised eye is required to see them.

As far as the Sheat-fishes are concerned, there is little need for the prohibition, inasmuch as the flesh is not at all agreeable in flavour, and is difficult of digestion, being very fat and gelatinous. The swimming-bladder of the Sheat-fish is used in some countries for making a kind of isinglass, similar in character to that of the sturgeon, but of coarser quality.

The lowermost figure in the illustration on page 566 represents a species which is exceedingly plentiful in the Sea of Galilee.

On account of the mode in which their body is covered, the whole of the sharks and rays are excluded from the list of permitted Fish, as, although they have fins, they have no scales, their place being taken by shields varying greatly in size. The same rule excludes the whole of the lamprey tribe, although the excellence of their flesh is well known.

Moreover, the Jews almost universally declare that the Muræna and Eel tribe are also unclean, because, although it has been proved that these Fishes really possess scales as well as fins, and are therefore legally permissible, the scales are hidden under a slimy covering, and are so minute as to be practically absent.

The uppermost figure in the illustration represents the celebrated Muræna, one of the fishes of the Mediterranean, in which sea it is tolerably plentiful. In the days of the old Roman empire, the Muræna was very highly valued for the table. The wealthier citizens built ponds in which the Murænæ were kept alive until they were wanted. This Fish sometimes reaches four feet in length.

The rest of the Fishes which are shown in the three illustrations belong to the class of clean Fish, and were permitted as food. The figure of the Fish between the Muræna and Sheat-fish is the Long-headed Barbel, so called from its curious form.

The Barbels are closely allied to the carps, and are easily known by the barbs or beards which hang from their lips. Like the sheat-fishes, the Barbels are fond of grubbing in the mud, for the purpose of getting at the worms, grubs, and larvæ of aquatic insects that are always to be found in such places. The Barbels are rather long in proportion to their depth, a peculiarity which, owing to the length of the head, is rather exaggerated in this species.

The Long-headed Barbel is extremely common in Palestine, and may be taken with the very simplest kind of net. Indeed, in some places, the fish are so numerous that a common sack answers nearly as well as a net.

It has been mentioned that the ancient Romans were in the habit of forming ponds in which the Murænæ were kept, and it is evident, from several passages of Scripture, that the Jews were accustomed to preserve fish in a similar manner, though they would not restrict their tanks or ponds to one species.

Allusion is made to this custom in the Song of Solomon: "Thy neck is as a tower of ivory; thine eyes like the fish-pools in Heshbon, by the gate of Bath-rabbim." The Hebrew Bible renders the passage in a slightly different manner, not specifying the particular kind of pool. "Thine eyes are as the pools in Heshbon by a gate of great concourse."

Buxtorf, however, in his Hebrew Lexicon, translates the word as "piscina," i.e. fish-pond. Now among the ruins of Heshbon may still be seen the remains of a large tank, which in all probability was one of the "fish-pools" which are mentioned by the sacred writer.

If we accept the rendering of the Authorized Version, it is shown that tanks or ponds were employed for this purpose, by a passage which occurs in the prophecy of Isaiah: "The fishers also shall mourn, and all they that cast angle into the brooks shall lament, and they that spread nets upon the waters shall languish.

"Moreover they that work in fine flax, and they that weave networks, shall be confounded.

"And they shall be broken in the purposes thereof, all that make sluices and ponds for fish" (xix. 8-10).

This passage, however, is rendered rather variously. The marginal translation of verse 10 substitutes the word "foundations" for "purposes," and the words "living things" for "fish." The Jewish Bible takes an entirely different view of the passage, and renders it as follows: "The fishers also shall groan, and all that cast angle into the river shall mourn, and they that spread nets upon the waters shall be languid.

"Moreover, they that work in combed flax and they that weave networks shall be confounded.

"And the props thereof shall be crushed; all working for wages are void of soul."

However, the mark of doubt is affixed to this last phrase, and it cannot be denied that the rendering of the Authorized Version is at all events more consistent than that of the Jewish Bible. In the former, we first find the fishers taking their prey with the hook and line, then with different kinds of nets, and lastly, placing the fish thus captured in sluices and ponds until they are wanted for consumption.

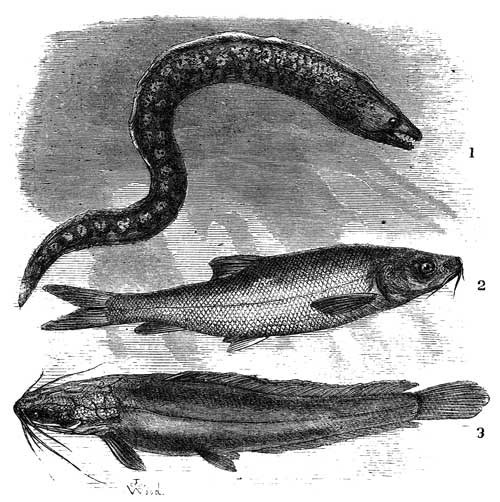

FISHES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN.

1. Sucking-fish (Echeneis remora). 2. Tunny (Thynnus thynnus).

3. Coryphene (Coryphæna hippuris).

"These shall ye eat of all that are in the waters."—Levit. xi. 9.]

The accompanying illustration represents Fishes of the Mediterranean Sea, and it is probable that one of them may be identified, though the passage in which it is mentioned is only an inferential one. In the prophecy against Pharaoh, king of Egypt, the prophet Ezekiel writes as follows: "I will put hooks in thy jaws, and I will cause the fish of thy rivers to stick unto thy scales, and I will bring thee up out of the midst of thy rivers, and all the fish of thy rivers shall stick unto thy scales" (xxix. 4).

Reference is here made to some inhabitant of the waters that has the power of adhesion, and two suggestions have been made respecting the precise signification of the passage. Some commentators think that the "Fishes" here mentioned are the Cuttles, which, although they are not Fishes at all, but belong to the molluscs, are called Fishes after the loose nomenclature of the Hebrew language, just as, even in our stricter and more copious language, we speak of the same creature as the Cuttle-fish, and use the word "shell-fish" to denote both molluscs and crustacea.

Others believe that the prophet made allusion to the Sucking-fish, which has the dorsal fins developed into a most curious apparatus of adhesion, by means of which it can fasten itself at will to any smooth object, and hold so tightly to it that it can scarcely be torn away without injury.

The common Sucking-fish (Echeneis remora) is shown in the upper part of the illustration.

There are, however, other fish which have powers of adhesion which, although not so remarkable as those of the Sucking-fish, are yet very strong. There is, for example, the well-known Lump-sucker, or Lump-fish, which has the ventral fins modified into a sucker so powerful that, when one of these fishes has been put into a pail of water, it has attached itself so firmly to the bottom of the vessel that when lifted by the tail it raised the pail, together with several gallons of water.

The Gobies, again, have their ventral fins united and modified into a single sucker, by means of which the fish is able to secure itself to a stone, rock, or indeed any tolerably smooth surface. These fishes are popularly known as Bull-routs.

The centre of the illustration is occupied by another of the Mediterranean fishes. This is the well-known Tunny (Thynnus thynnus), which furnishes food to the inhabitants of the coasts of this inland sea, and indeed constitutes one of their principal sources of wealth. This fine fish is on an average four or five feet in length, and sometimes attains the length of six or seven feet.

The flesh of the Tunny is excellent, and the fish is so conspicuous, that the silence of the Scriptures concerning its existence shows the utter indifference to specific accuracy that prevailed among the various writers.

The other figure represents the Coryphene (Coryphæna hippuris), popularly, though very wrongly, called the Dolphin, and celebrated, under that name, for the beautiful colours which fly over the surface of the body as it dies.

The flesh of the Coryphene is excellent, and in the times of classic Rome the epicures were accustomed to keep these fish alive, and at the beginning of a feast to lay them before the guests, so that they might, in the first place, witness the magnificent colours of the dying fish, and, in the second place, might be assured that when it was cooked it was perfectly fresh. Even during life, the Coryphene is a most lovely fish, and those who have witnessed it playing round a ship, or dashing off in chase of a shoal of flying-fishes, can scarcely find words to express their admiration of its beauty.

CHAPTER II

Various modes of capturing Fish—The hook and line—Military use of the hook—Putting a hook in the jaws—The fishing spear—Different kinds of net—The casting-net—Prevalence of this form—Technical words among fishermen—Fishing by night—The draught of Fishes—The real force of the miracle—Selecting the Fish—The Fish-gate and Fish-market—Fish killed by a draught—Fishing in the Dead Sea—Dagon, the fish-god of Philistina, Assyria, and Siam—Various Fishes of Egypt and Palestine.

As to the various methods of capturing Fish, we will first take the simplest plan, that of the hook and line, as is mentioned in the passage quoted above from Ezekiel. Sundry other references are made to angling, both in the Old and New Testaments. See, for example, the well-known passage respecting the leviathan, in Job xli. 1, 2: "Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook? or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down?

"Canst thou put an hook into his nose? or bore his jaw through with a thorn?"

It is thought that the last clause of this passage refers, not to the actual capture of the Fish, but to the mode in which they were kept in the tanks, each being secured by a ring or hook and line, so that it might be taken when wanted.

On referring to the New Testament, we find that the fisher Apostles used both the hook and the net. See Matt. xvii. 27: "Go thou to the sea, and cast an hook, and take up the fish that first cometh up." Now this passage explains one or two points.

In the first place, it is one among others which shows that, although the Apostles gave up all to follow Christ, they did not throw away their means of livelihood, as some seem to fancy, nor exist ever afterwards on the earnings of others. On the contrary, they retained their fisher equipment, whether boats, nets, or hooks; and here we find St. Peter, after the way of fishermen, carrying about with him the more portable implements of his craft.

Next, the phrase "casting" the hook into the sea is exactly expressive of the mode in which angling is conducted in the sea and large pieces of water, such as the Lake of Galilee. The fisherman does not require a rod, but takes his line, which has a weight just above the hook, coils it on his left arm in lasso fashion, baits the hook, and then, with a peculiar swing, throws it into the water as far as it will reach. The hook is allowed to sink for a short time, and is then drawn towards the shore in a series of jerks, in order to attract the Fish, so that, although the fisherman does not employ a rod, he manages his line very much as does an angler of our own day when "spinning" for pike or trout.