полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

"But the tongue can no man tame; it is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison."

How the serpent-charmers perform their feats is not very intelligible. That they handle the most venomous Serpents with perfect impunity is evident enough, and it is also clear that they are able to produce certain effects upon the Serpents by means of musical (or unmusical) sounds. But these two items are entirely distinct, and one does not depend upon the other.

In the first place, the handling of venomous snakes has been performed by Englishmen without the least recourse to any arts except that of acquaintance with the habits of Serpents. The late Mr. Waterton, for example, would take up a rattlesnake in his bare hand without feeling the least uneasy as to the behaviour of his prisoner. He once took twenty-seven rattlesnakes out of a box, carried them into another room, put them into a large glass case, and afterwards replaced them in the box. He described to me the manner in which he did it, using my wrist as the representative of the Serpent.

The nature of all Serpents is rather peculiar, and is probably owing to the mode in which the blood circulates. They are extremely unwilling to move, except when urged by the wants of nature, and will lie coiled up for many hours together when not pressed by hunger. Consequently, when touched, their feeling is evidently like that of a drowsy man, who only tries to shake off the object which may rouse him, and composes himself afresh to sleep.

A quick and sudden movement would, however, alarm the reptile, which would strike in self-defence, and, sluggish as are its general movements, its stroke is delivered with such lightning rapidity that it would be sure to inflict its fatal wound before it was seized. If, therefore, Mr. Waterton saw a Serpent which he desired to catch, he would creep very quietly up to it, and with a gentle, slow movement place his fingers round its neck just behind the head. If it happened to be coiled up in such a manner that he could not get at its neck, he had only to touch it gently until it moved sufficiently for his purpose.

When he had once placed his hand on the Serpent, it was in his power. He would then grasp it very lightly indeed, and raise it gently from the ground, trusting that the reptile would be more inclined to be carried quietly than to summon up sufficient energy to bite. Even if it had tried to use its fangs, it could not have done so as long as its captor's fingers were round its neck.

As a rule, a great amount of provocation is needed before a venomous Serpent will use its teeth. One of my friends, when a boy, caught a viper, mistaking it for a common snake. He tied it round his neck, coiled it on his wrist by way of a bracelet, and so took it home, playing many similar tricks with it as he went. After arrival in the house, he produced the viper for the amusement of his brothers and sisters, and, after repeating his performances, tried to tie the snake in a double knot. This, however, was enough to provoke the most pacific of creatures, and in consequence he received a bite on his finger.

There is no doubt that the snake-charmers trust chiefly to this sluggish nature of the reptile, but they certainly go through some ceremonies by which they believe themselves to be rendered impervious to snake-bites. They will coil the cobra round their naked bodies, they will irritate the reptile until it is in a state of fury; they will even allow it to bite them, and yet be none the worse for the wound. Then, as if to show that the venomous teeth have not been abstracted, as is possibly supposed to be the case, they will make the cobra bite a fowl, which speedily dies from the effects of the poison.

Even if the fangs were extracted, the Serpents would lose little of their venomous power. These reptiles are furnished with a whole series of fangs in different stages of development, so that when the one in use is broken or shed in the course of nature, another comes forward and fills its place. There is now before me a row of four fangs, which I took from the right upper jawbone of a viper caught in the New Forest.

In her interesting "Letters from Egypt," Lady Duff-Gordon gives an amusing account of the manner in which she was formally initiated into the mysteries of snake-charming, and made ever afterwards impervious to the bite of venomous Serpents:—

"At Kóm Omboo, we met with a Rifáee darweesh with his basket of tame snakes. After a little talk, he proposed to initiate me: and so we sat down and held hands like people marrying. Omar [her attendant] sat behind me, and repeated the words as my 'wakeel.' Then the Rifáee twisted a cobra round our joined hands, and requested me to spit on it; he did the same, and I was pronounced safe and enveloped in snakes. My sailors groaned, and Omar shuddered as the snakes put out their tongues; the darweesh and I smiled at each other like Roman augurs."

She believed that the snakes were toothless; and perhaps on this occasion they may have been so. Extracting the teeth of the Serpent is an easy business in experienced hands, and is conducted in two ways. Those snake-charmers who are confident of their own powers merely grasp the reptile by the neck, force open its jaws with a piece of stick, and break off the fangs, which are but loosely attached to the jaw. Those who are not so sure of themselves irritate the snake, and offer it a piece of cloth, generally the corner of their mantle, to bite. The snake darts at it, and, as it seizes the garment, the man gives the cloth a sudden jerk, and so tears away the fangs.

Still, although some of the performers employ mutilated snakes, there is no doubt that others do not trouble themselves to remove the fangs of the Serpents, but handle with impunity the cobra or the cerastes with all its venomous apparatus in good order.

We now come to the second branch of the subject, namely, the influence of sound upon the cobra and other Serpents. The charmers are always provided with musical instruments, of which a sort of flute with a loud shrill sound is the one which is mostly used in the performances. Having ascertained, from slight marks which their practised eyes easily discover, that a Serpent is hidden in some crevice, the charmer plays upon his flute, and in a short time the snake is sure to make its appearance.

As soon as it is fairly out, the man seizes it by the end of the tail, and holds it up in the air at arm's length. In this position it is helpless, having no leverage, and merely wriggles about in fruitless struggles to escape. Having allowed it to exhaust its strength by its efforts, the man lowers it into a basket, where it is only too glad to find a refuge, and closes the lid. After a while, he raises the lid and begins to play the flute.

The Serpent tries to glide out of the basket, but, as soon as it does so, the lid is shut down again, and in a very short time the reptile finds that escape is impossible, and, as long as it hears the sound of the flute, only raises its head in the air, supporting itself on the lower portion of its tail, and continues to wave its head from side to side as long as it hears the sound of the music.

The rapidity with which a cobra learns this lesson is extraordinary, the charmers being as willing to show their mastery over newly-caught Serpents as over those which have been long in their possession. Some persons have thought that all the snakes caught by the professional charmers are tame reptiles, which have been previously placed in the hole by the men, and which have been deprived of their fangs. Careful investigations, however, have proved that the snake is really attracted by the shrill notes of the flute, and that the charmers handle with unconcern the snakes which are in full possession of their fangs and poison-glands.

The allusion to the "deaf adder, which stoppeth her ears." needs a little explanation. Some species of Serpent are more susceptible to sound than others, the cobra being the most sensitive of all the tribe. Any of these which are comparatively insensible to the charmers efforts may be considered as "deaf adders." But there has been from time immemorial a belief in the East that some individual Serpents are very obstinate and self-willed, refusing to hear the shrill sound of the flute, or the magic song of the charmer, and pressing one ear into the dust, while they stop the other with the tail.

Louis of Grenada, one of whose quaint sermons has already been quoted, alludes in another discourse to this curious belief, in which it is evident that he fully concurred.

"Dominica XI. post Pent. Concio 1:

"'Furor illis secundum similitudinem serpentis sicut aspidis et obturantis aures suas; quæ non exaudit vocem incantantium, et venefici incantantis sapienter.'

"Vulgo enim ferunt aspidem cum incantatur ne lethali veneno homines inficiat, alteram aurem terræ affigere, alteram vero cauda in eam immissa obstruere ut ita demum veneni vis intus latentis illæsa maneat.

"Ad hoc igitur modum cum sapiens incantatur, hoc est, divini verbi concionator obstinatos homines ad sanitatem perducere et lethale venenum peccati, quod in eorum mentibus residet delere contendit; illi contra (dæmone id operante) sic aures suas huic divinæ incantationi claudunt ut nihil prorsus eorum quæ dicuntur advertant."

"Eleventh Sunday after Pentecost, Sermon 1:

"'Their fury is after the likeness of the serpent, as the asp which even stoppeth her ears—which heedeth not the voice of the charmers; even of the wizard which charmeth wisely.'

"For they say commonly, the asp while she is charmed, so that she poisoneth not men with her deadly venom, layeth one of her ears to the ground and stoppeth the other by thereinto putting her tail, that so the strength of the poison which lurketh within may abide unhurt.

"After this manner, therefore, when the wise charmer—that is, the preacher of the Word of God—striveth to lead obstinate men to health, and to destroy the deadly poison of sin which dwelleth in their minds, they, on the other hand (the devil bringing this to pass), do so shut their ears to this divine charming that they heed nothing at all of these things which are said."

In order to show how widely this idea of the snake stopping its ears is spread, I insert the following extract from a commentary on the Psalms by Richard Rolle (Hermit) of Hampole. It is taken from the MS. in Eton College Library, No. 10, date 1450. R. Rolle died just a hundred years before his commentary was translated into the Northern dialect.

"'Furor illis sec̃dm̃ similitudinẽ s̃pentis: sicut aspidus surde et obturantis aures suas.' ¶ Wodnes til Þase after Þe lykenying of nedder: als of snake doumbe and stoppand hir erres. ¶ Rightly calles he Þaĩ wode for Þai haue na witt to se whider Þai ga for Þai louke Þaire eghen and rennes til Þe fire Þaire wodnes es domested Þat will not be t̃ned als of Þe snake Þat festes Þe tane ere till Þe erther and Þe toÞer stopis with hir̃ tayle swa Þai do Þat here noght godes worde Þai stoppe Þair̃ erres with lufe of erthely thyng Þat Þai delite Þai one and with Þaire tayle Þat es with aide synes Þat Þai will noght amende."

It may be as well to remark, before passing to another of the Serpents, that snakes have no external ears, and that therefore the notion of the serpent stopping its ears is zoologically a simple absurdity.

THE CERASTES, OR SHEPHIPHON OF SCRIPTURE

The word shephiphon, which evidently signifies some species of snake, only occurs once in the Scriptures, but fortunately that single passage contains an allusion to the habits of the serpent which makes identification nearly certain. The passage in question occurs in Gen. xlix. 17, and forms part of the prophecy of Jacob respecting his children: "Dan shall be a serpent by the way, an adder in the path, that biteth the horses heels, so that his rider shall fall backward."

Putting aside the deeper meaning of this prophecy, there is here an evident allusion to the habits of the Cerastes, or Horned Viper, a species of venomous serpent, which is plentiful in Northern Africa, and is found also in Palestine and Syria. It is a very conspicuous reptile, and is easily recognised by the two horn-like projections over the eyes. The name Cerastes, or horned, has been given to it on account of these projections.

This snake has a custom of lying half buried in the sand, awaiting the approach of some animal on which it can feed. Its usual diet consists of the jerboas and other small mammalia, and as they are exceedingly active, while the Cerastes is slow and sluggish, its only chance of obtaining food is to lie in wait. It will always take advantage of any small depression, such as the print of a camel's foot, and, as it finds many of these depressions in the line of the caravans, it is literally "a serpent by the way, an adder in the path."

According to the accounts of travellers, the Cerastes is much more irritable than the cobra, and is very apt to strike at any object which may disturb it. Therefore, whenever a horseman passes along the usual route, his steed is very likely to disturb a Cerastes lying in the path, and to be liable to the attack of the irritated reptile. Horses are instinctively aware of the presence of the snake, and mostly perceive it in time to avoid its stroke. Its small dimensions, the snake rarely exceeding two feet in length, enable it to conceal itself in a very small hollow, and its brownish-white colour, diversified with darker spots, causes it to harmonize so thoroughly with the loose sand in which it lies buried, that, even when it is pointed out, an unpractised eye does not readily perceive it.

Even the cobra is scarcely so dreaded as this little snake, whose bite is so deadly, and whose habits are such as to cause travellers considerable risk of being bitten.

THE VIPER, OR EPHEH

Passages in which the word Epheh occurs—El-effah—The Sand Viper, or Toxicoa—Its appearance and habits—The Acshub—Adder's poison—The Spuugh-Slange—The Cockatrice, or Tsepha—The Yellow Viper—Ancient ideas concerning the Cockatrice—Power of its venom.

We now come to the species of snake which cannot be identified with any certainty, and will first take the word epheh, which is curiously like to the Greek ophis. From the context of the three passages in which it occurs, it is evidently a specific, and not a collective name, but we are left in much doubt as to the precise species which is intended by it. The first of those passages occurs in Job xx. 16: "The viper's (epheh) tongue shall slay him." The second is found in Isa. xxx. 6: "The burden of the beasts of the south: into the land of trouble and anguish, from whence come the young and old lion, the viper (epheh) and fiery flying serpent." The last of these passages occurs in ch. lix. 5 of the same book: "That which is crushed breaketh out into a viper" (epheh).

The reader will see that in neither of those passages have we the least intimation as to the particular species which is signified by the word epheh, and the only collateral evidence which we have on the subject fails exactly in the most important point. We are told by Shaw that in Northern Africa there is a small snake, the most poisonous of its tribe, which is called by the name of El-effah, a word which is absolutely identical with the Epheh of the Old Testament. But, as he does not identify the effah, except by saying that it rarely exceeds a foot in length, we gain little by its discovery.

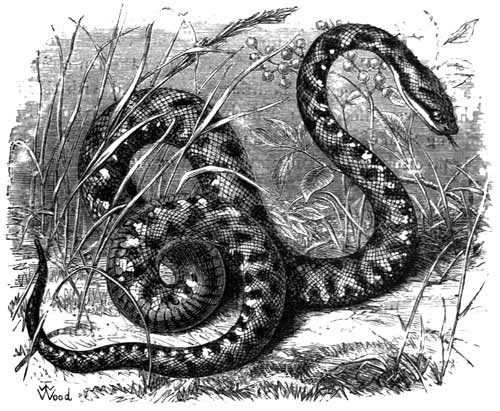

Mr. Tristram believes that he has identified the Epheh of the Old Testament with the Sand-Viper, or Toxicoa (Echis arenicola). This reptile, though very small, and scarcely exceeding a foot in length, is a dangerous one, though its bite is not so deadly as that of the cobra or cerastes. It is variable in colour, but has angular white streaks on its body, and a row of whitish spots along the back. The top of the head is dark, and variegated with arrow-shaped white marks.

THE TOXICOA. (Supposed to be the viper of Scripture.)

"The viper's tongue shall slay him."—Job xx. 16.

The Toxicoa is very plentiful in Northern Africa, Palestine, Syria, and the neighbouring countries, and, as it is exceedingly active, is held in some dread by the natives. The Toxicoa is closely allied to the dreaded Horatta-pam snake of India (Echis carinata).

The old Hebraists can make nothing of the word, but it is not unlikely that a further and fuller investigation of the ophiology of Northern Africa may succeed where mere scholarship, unallied with zoological knowledge, has failed.

The next word is acshub (pronounced ăk-shoob). It only occurs in one passage, namely Ps. cxl. 3: "They have sharpened their tongues like a serpent (nachash); adder's (acshub) poison is under their lips." The precise species represented by this word is unknown. Buxtorf, however, explains the word as the Spitter, "illud genus quod venenum procul exspuit." Now, if we accept this derivation, we must take the word acshub as a synonym for pethen. We have already identified the Pethen with the Naja haje, a snake which has the power of expelling the poison to some distance, when it is out of reach of its enemy. Whether the snake really intends to eject the poison, or whether it is merely flung from the hollow fangs by the force of the suddenly-checked stroke, is uncertain. That the Haje cobra can expel its poison is an acknowledged fact, and the Dutch colonists of the Cape have been so familiarly acquainted with this habit, that they have called this reptile by the name of Spuugh-Slange, or Spitting Snake, a name which, if we accept Buxtorf's etymology, is precisely equivalent to the word acshub.

Another name of a poisonous snake occurs several times in the Old Testament. The word is tsepha, or tsiphôni, and it is sometimes translated as Adder, and sometimes as Cockatrice. The word is rendered as Adder in Prov. xxiii. 32, where it is said that wine "biteth like a serpent, and stingeth like an adder." Even in this case, however, the word is rendered as Cockatrice in the marginal translation.

It is found three times in the Book of Isaiah. Ch. xi. 8: "The weaned child shall put his hand on the cockatrice' den." Also, ch. xiv. 29: "Rejoice not thou, whole Palestina, because the rod of him that smote thee is broken: for out of the serpent's (nachash) nest shall come forth a cockatrice (tsepha), and his fruit shall be a fiery flying serpent." The same word occurs again in ch. lix. 5: "They hatch cockatrice' eggs." In the prophet Jeremiah we again find the word: "For, behold, I will send serpents, cockatrices among you, which will not be charmed, and they shall bite you, saith the Lord."

This last passage gives us a little, but not much, assistance in identifying the Tsepha. We learn by it that the Tsepha was one of the serpents that were not subject to charmers, and so we are able to say that it was neither the cobra, which we have identified with the Pethen of Scripture, nor the Cerastes or Horned Snake, which has been shown to be the Shephiphon. Our evidence is therefore only of a negative character, and the only positive evidence is that which may be inferred from the passage in Isa. xiv. 29, where the Tsepha is evidently thought to be more venomous than the ordinary serpent or Nachash.

Mr. Tristram suggests that the Tsepha of Scripture may possibly be the Yellow Viper (Daboia xanthica), which is one of the largest and most venomous of the poisonous serpents which are found in Palestine, and which is the more dangerous on account of its nocturnal habits. This snake is one of the Katukas, and is closely allied to the dreaded Tic-polonga of Ceylon, a serpent which is so deadly, and so given to infesting houses, that one of the judges was actually driven out of his official residence by it.

As to the old ideas respecting the origin of the Cockatrice, a very few words will suffice for them. This serpent was thought to be produced from an egg laid by a cock and hatched by a viper. "For they say," writes Topsel, "that when a cock groweth old, he layeth a certain egge without any shell, in stead whereof it is covered with a very thick skin, which is able to withstand the greatest force of an easie blow or fall. They say moreover that this Egge is laid only in the summer time, about the beginning of Dog days, being not so long as a Hen's Egge, but round and orbicular. Sometimes of a dirty, sometimes of a boxy, and sometimes of yellowish muddy colour, which Egge, afterwards sat upon by a Snake or a Toad, bringeth forth the Cockatrice, being half a foot in length, the hinder part like a Snake, the former part like a Cock, because of a treble combe on his forehead.

"But the vulgar opinion of Europe is, that the Egge is nourished by a Toad, and not by a Snake; howbeit in better experience it found that the Cock doth sit on that Egge himself: whereof Serianus Semnius in his twelfth book of the Hidden Animals of Nature hath this discourse, in the fourth chapter thereof. 'There happened,' saith he, 'within our memory, in the city of Pirizæa, that there were two old Cocks which had laid Egges, and the common people (because of opinion that those Egges would engender Cockatrices) laboured by all meanes possible to keep the same Cocks from sitting on those Egges, but they could not with clubs and staves drive them from the Egges, until they were forced to break the Egges in sunder, and strangle the Cocks."

In this curious history it is easy to see the origin of the notion respecting the birth of the Cockatrice. It is well known that hens, after they have reached an advanced age, assume much of the plumage and voice of the male bird. Still, that one of them should occasionally lay an egg is no great matter of wonder, and, as the egg would be naturally deposited in a retired and sheltered spot, such as would be the favoured haunts of the warmth-loving snake, the ignorant public might easily put together a legend which, absurd in itself, is yet founded on facts. The small shell-less egg, so often laid by poultry, is familiar to every one who has kept fowls.

Around this reptile a wonderful variety of legends have been accumulated. The Cockatrice was said to kill by its very look, "because the beams of the Cockatrice's eyes do corrupt the visible spirit of a man, which visible spirit corrupted all the other spirits coming from the brain and life of the heart, are thereby corrupted, and so the man dyeth."

The subtle poison of the Cockatrice infected everything near it, so that a man who killed a Cockatrice with a spear fell dead himself, by reason of the poison darting up the shaft of the spear and passing into his hand. Any living thing near which the Cockatrice passed was instantly slain by the fiery heat of its venom, which was exhaled not only from its mouth, but its sides. For the old writers, whose statements are here summarized, contrived to jumble together a number of miscellaneous facts in natural history, and so to produce a most extraordinary series of legends. We have already seen the real origin of the legend respecting the egg from which the Cockatrice was supposed to spring, and we may here see that some one of these old writers has in his mind some uncertain floating idea of the respiratory orifices of the lamprey, and has engrafted them on the Cockatrice.

"To conclude," writes Topsel, "this poyson infecteth the air, and the air so infected killeth all living things, and likewise all green things, fruits, and plants of the earth: it burneth up the grasse whereupon it goeth or creepeth, and the fowls of the air fall down dead when they come near his den or lodging. Sometimes he biteth a Man or a Beast, and by that wound the blood turneth into choler, and so the whole body becometh yellow as gold, presently killing all who touch it or come near it."

I should not have given even this limited space to such puerile legends, but for the fact that such stories as these were fully believed in the days when the Authorized Version of the Bible was translated. The ludicrous tales which have been occasionally mentioned formed the staple of zoological knowledge, and an untravelled Englishman had no possible means of learning the history of foreign animals, except from such books which have been quoted, and which were in those days the standard works on Natural History. The translators of the Bible believed most heartily in the mysterious and baleful reptile, and, as they saw that the Tsepha of Scripture was an exceptionally venomous serpent, they naturally rendered it by the word Cockatrice.