полная версия

полная версияThe American Race

338

“Nullam gentem Christianis moribus capessendis aut retiendis aptiorem in australi hoc America fuisse repertam.” Nicolas del Techo, loc. cit., Lib. X., Cap. 9.

339

Comp. von Martius, u. s., s. 179.

340

Reise in Chile und Peru, Bd. II., s. 450.

341

“Though widely different from the Tupi, ancient or modern, I am satisfied that the Mundurucú belongs to the same family.” C. F. Hartt, in Trans. of the Amer. Philological Association, 1872, p. 75.

342

Von Martius, Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerikas, Bd. I., s. 412. A specimen of their vocalic and sonorous language is given by E. Teza, Saggi Inediti di Lingue Americane, p. 43. (Pisa, 1868.)

343

G. Coleti, Dizionario Storico-Geografico dell’ America Meridionale, Tom. II., p. 38. (Venezia, 1771.)

344

Lozano, Hist. de la Conquista de Paraguay, pp. 415, 416.

345

Lozano, Ibid., pp. 422-425.

346

Paul Marcoy, Voyage à travers l’Amérique du Sud, Tome II., p. 241; comp. Waitz, Anthropologie der Naturvölker, Bd. III., s. 427.

347

The “Amazon-stones,” muira-kitan, are ornaments of hard stone, as jade or quartz.

348

H. Müller, in Compte Rendue du Congrès Internat. des Américanistes, 1888, p. 461.

349

Dr. P. M. Rey, Etude Anthropologique sur les Botocudos, p. 51 and passim. (Paris, 1880.) Dr. Paul Ehrenreich, “Ueber die Botocudos,” in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1887, Heft I.

350

Von Tschudi, Reise in Sud Amerika, Bd. II., p. 281. If this is one of their ancient arts, it is the only instance of the invention of an artificial light south of the Eskimos in America.

351

Dr. P. M. Rey states that the custom of kissing is known to them both as a sign of peace between men, and of affection from mothers to children. (Et de Anthropologique sur les Botocudos, p. 74, Paris, 1880.) This is unusual, and indeed I know no other native tribe who employed this sign of friendship.

352

Dr. Rey, loc. cit., p. 78, 79.

353

In the Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1887, s. 49.

354

A comparative vocabulary of these dialects is given by Von Martius, Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerikas, Bd. I., s. 310.

355

In the Transactions of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1886, p. 329. The terms for comparison are borrowed from Von den Steinen’s Comparative Vocabulary of the Tapuya Dialects.

356

See D. G. Brinton, “The Arawack Language of Guiana in its Linguistic and Ethnological Relations,” in Trans. of the Amer. Phil. Soc., 1871.

357

Olivier Ordinaire, “Les Sauvages du Perou,” in Revue d’Ethnographie, 1887, p. 282.

358

C. Greiffenstein, in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1878, s. 137.

359

Von Tschudi, Organismus der Kechua Sprache, p. 67. For other members of the Campas see Hervas, Catalogo de las Lenguas Conocidas, Tom. I., p. 262; Amich, Compendio Historico de la Serafica Religion, p. 35, and Scottish Geog. Journal, Feb., 1890.

360

D’Orbigny, L’Homme Américain, Tom. II., p. 104, note.

361

“Los Guanas son la mejor nacion de las barbaras hasta ahora descubiertas en America.” Hervas, Catalogo de las Lenguas Conocidas, Tom. I., p. 189.

362

Expédition dans l’Amérique du Sud, Tome II., p. 480.

363

Compte-Rendu du Cong. Internat. des Américanistes, 1888, p. 510.

364

The words from the Paiconeca and Saraveca are from D’Orbigny, L’Homme Américain, Tome I., p. 165; those from the Arawak stock from the table in Von den Steinen, Durch Central-Brasilien, s. 294.

365

Im Thurn, Among the Indians of Guiana, p. 165. Comp. Von den Steinen, Durch Central Brasilien, ss. 295, 307.

366

Sir Robert H. Schomburgk, in Report of the Brit. Assoc. for the Adv. of Science, 1848, pp. 96-98. See also Im Thurn, u. s., pp. 163, 272; Martius, Ethnographie, Bd. I., s. 683.

367

Lucien Adam, Compte-Rendu du Congrès Internat. d’Américanistes, 1888, p. 492.

368

“All the numerous branches of this stem,” says Virchow, “present the same type of skull.” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1886, s. 695.

369

Everard F. im Thurn, Among the Indians of Guiana, p. 189. (London, 1883.)

370

F. X. Eder, Descriptio Provinciæ Moxitarum, p. 217. (Budæ, 1791.) Dr. Washington Matthews has kindly made for me a number of observations upon Navajo Indians with reference to this anatomical peculiarity. It is not markedly present among them.

371

For particulars see Im Thurn, ubi suprá, Chap. VII.

372

Von Martius, Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerikas, Bd. I., s. 625-626.

373

Karl von den Steinen, Durch Central-Brasilien, Cap. XXI., “Die Heimat der Kariben.”

374

Im Thurn, Among the Indians of Guiana, p. 171-3.

375

See Francisco de Tauste, Arte, Bocabulario, y Catecismo de la Lengua de Cumana, p. 1 (Ed. Julius Platzmann).

376

They are printed in the Berlin Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1878.

377

Chaffanjon, L’Orénoque et le Caura, p. 308 (Paris, 1889).

378

Joao Barboza Rodrigues, Pacificaçáo dos Crichanas, (Rio de Janeiro, 1885). Dr. Rodrigues was Director of the Botanical Museum of the Amazons. His work contains careful vocabularies of over 700 words in the Macuchi, Ipurucoto and Crichana dialects. His journeys to the Rio Jauapery were undertaken chiefly from philanthropic motives, which unfortunately did not bear the fruit they merited.

379

“D’un blanc presque pur.” Dr. J. Crévaux, Voyages dans l’Amérique du Sud, p. 111 (Paris, 1883).

380

Dr. Crévaux, Ibid., p. 304.

381

See Dr. Paul Ehrenreich, in the Verhandlungen der Berliner Anthrop. Gesell., 1888, p. 549. These are not to be confounded with the Apiacas of the Rio Arinos, who are of Tupi stock. The word apiaca or apiaba in Tupi means simply “men.”

382

A. S. Pinart, Aperçu sur d’ile d’Aruba, ses Habitants, ses Antiquités, ses Petroglyphes (folio, Paris, 1890).

383

Report of the Brit. Assoc. for the Adv. of Science, 1848, p. 96.

384

Bulletin of the Amer. Ethnolog. Society, Vol. I., p. 59.

385

The identification of the Motilones as Caribs we owe to Dr. Ernst, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1887, s. 296.

386

“La mas bella, la mas robusta y la mas intelligente,” etc. F. Michelena y Rojas, Exploracion Official de la America del Sur, p. 54 (Bruselas, 1867).

387

See D. G. Brinton, “On a Petroglyph from the Island of St. Vincent,” in Proceedings of the Acad. of Nat. Sciences of Philadelphia, 1889, p. 417.

388

Also the Ouayéoué, of which a short vocabulary is given by M. Coudreau in the Archives de la Société Américaine de France, 1886.

389

Martius, Ethnographie, Bd. I., s. 346, sq. The word may mean either maternal or paternal uncle, V. d. Steinen, s. 292.

390

Luiz Vincencio Mamiani, Arte de la Lingua Kiriri, and his Catechismo na Lingua da naçao Kiriri. The former has been republished (1877), and also translated into German by Von der Gabelentz (1852).

391

Durch Central-Brasilien, s. 303. This writer looks upon the Cariris as a remote off-shoot from the Carib stock.

392

See Von den Steinen, Durch Central-Brasilien, s. 320; Paul Ehrenreich, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1886, s. 184.

393

Reinhold Hensel, “Die Coroados der Provinz Rio Grande do Sul,” in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, Bd. II., s. 195.

394

F. de Castelnau, Expédition dans l’Amérique du Sud, Tom. I., p. 446.

395

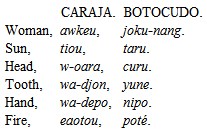

For instance:

Dr. Paul Ehrenreich, who has a mass of unpublished material about the Caraja language, says it is wholly unconnected with the Carib group. Verhandlungen der Berliner Anthrop. Gesell., 1888, p. 548.

396

Vocabularies of these are collected by Von Martius in his Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerikas, Bd. II., ss. 155, 156, 161, 212, etc.

397

The list is given in his Personal Narrative of a Journey in the Equinoctial Regions of America, Vol. VI., pp. 354-358, of the English translation (London, 1826).

398

F. S. Gilii, Saggio di Storia Americana, Tom. III., Lib. III., cap. 12 (Roma, 1782). In speaking of lengue matrici, he says positively, “In tutta l’estensione del grande Orinoco non ve ne sono che nove,” p. 204.

399

Aug. Codazzi, Geografia de Venezuela, pp. 247, 248 (Paris, 1841).

400

J. Chaffanjon, L’Orénoque et la Caura, p. 247 (Paris, 1889).

401

Michelena y Rojas, Exploracion Oficial de la America del Sur, p. 344 (Bruselas, 1867).

402

A. Coudreau, Archives de la Société Américaine de France, 1885, p. 281.

403

L’Orénoque et le Caura, p. 183.

404

See the Vocabularies.

405

Consult J. Cassani, Historia de la Provincia de la Compañia de Jesus del Nuevo Reyno de Granada, fol. 170, 227 (Madrid, 1741); and Joseph Gumilla, El Orinoco Ilustrado y Defendido, p. 65 (Madrid, 1745).

406

Quoted by Aristides Rojas, Estudios Indigenas, p. 183 (Caracas, 1878). This work contains much useful information on the Venezuelan languages.

407

Jorge S. Hartmann, “Indianerstämme von Venezuela,” in Orig. Mittheil. aus der Ethnol. Abtheil. der König. Museen zu Berlin, 1886, s. 162.

408

Joseph Gumilla, El Orinoco, p. 66.

409

Felipe Perez, Geografia del Estado de Cundinamarca, p. 109.

410

Historia de la Provincia de Granada, pp. 87, 93. He calls them a “nacion suave y racional.”

411

Felipe Perez, Geografia del Estado de Boyuca, p. 136.

412

G. D. Coleti, Dizionario Storico-Geografico dell’ America Meridionale, Tom. I. p. 164 (Venezia, 1772).

413

J. Chaffanjon, L’Orénoque et le Caura, p. 121.

414

“Los Gitanos de las Indias, todo parecido en costumbres y modo de vivir de nuestros Gitanos.” Cassani, Hist. de la Prov. de Granada, p. 111. Gumilla remarks: “De la Guajiva salen varias ramas entre la gran variedad de Chiricoas.” (El Orinoco Ilustrado, etc. Tom. II. p. 38.)

415

Chaffanjon, L’Orénoque et le Caura, pp. 177, 183, 187, 197.

416

The subject is fully discussed from long personal observation by Michelena y Rojas, Exploracion Oficial de la America del Sur, p. 346.

417

See the observations of Level in Michelena y Rojas, Exploracion Oficial de la America del Sur, p. 148, sq. The Guaraunos are also well described by Crévaux, Voyages dans l’Amérique du Sud, p. 600, sqq. (Paris, 1883), and J. Chaffanjon, Archives de la Société Américaine de France, 1887, p. 189. Im Thurn draws a very unfavorable picture of them in his Indians of British Guiana, p. 167.

418

A. Von Humboldt, Personal Narrative, Vol. III., p. 216 (Eng. trans. London, 1826).

419

Joseph Gumilla, L’Orinoco Ilustrado, Tom. II., p. 66. They spoke Carib to him, but that was the lengua general of the lower river.

420

A description of the Correguages and a vocabulary of their dialect are given by the Presbyter Manuel M. Albis, in Bulletin of the Amer. Ethnol. Soc., Vol. I., p. 55.

421

Arthur Simpson, Travels in the Wilds of Ecuador, p. 196 (London, 1886). In his appendix the author gives a vocabulary of the Pioje (and also one of the Zaparo).

422

Printed in the Bibliothèque Linguistique Américaine, by M. L. Adam, Tome VIII., p. 52.

423

Manuel P. Albis, in Bull. of the Amer. Ethnol. Society, Vol. I., p. 55.

424

See the account in the interesting work of Father Cassani, Historia de la Provincia de la Compañia de Jesus del Nuevo Reyno de Granada, pp. 231, 232, 257, etc. (Madrid, 1741). He describes the Jiraras as having the same rites, customs and language as the Airicos on the river Ele, p. 96. Gumilla makes the following doubtful statement: “De la lengua Betoya y Jirara, que aunque esta gasta pocas erres, y aquella demasiadas, ambas quieren ser matrices, se derivan las lenguas Situfa, Ayrica, Ele, Luculia, Jabue, Arauca, Quilifay, Anaboli, Lolaca, y Atabaca.” (El Orinoco Ilustrado y Defendido, Tom. II., p. 38, Madrid, 1745.)

425

Felipe Perez, Geografia del Estado de Cundinamarca, p. 113.

426

In the Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1876, s. 336, sq.

427

Geografia del Estado de Cundinamarca, p. 114 (Bogota, 1863).

428

Ibid., Geografia del Estado de Cauca, p. 313.

429

Chaffanjon, ubi suprá, p. 203.

430

He gives oueni, water, zenquerot, moon, as identical in the Puinavi and Baniva. The first may pass, but the second is incorrect. See his remarks in A. R. Wallace, Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro, p. 528 (London, 1853). A vocabulary of 53 Puinavi words is furnished from Dr. Crévaux’s notes in Vol. VIII. of the Bibliothèque Linguistique Américaine (Paris, 1882).

431

Ed. André, in Le Tour du Monde, 1883, p. 406. But Osculati describes them as tall and fine-looking, with small mustaches. Esplorazione delle Regioni Equatoriali, p. 164, sq. (Milano, 1850).

432

This opinion is supported by Hamy, Villavicencio, and other good authorities.

433

Hervas, Catal. de las Lenguas Conocidas, Tom. I., p. 262. The term Encabellados was applied to the tribe from their custom of allowing the hair to grow to their waist. (Lettres Edifiantes, Tom. II., p. 112). The Pater Noster in the Encabellada dialect is printed by E. Teza in his Saggi Inediti di Lingue Americane, p. 53 (Pisa, 1868).

434

In the closing chapters of his Esplorazione, above quoted.

435

An excellent article on the ethnography of this tribe is the “Osservazioni Ethnografiche sui Givari,” by G. A. Colini in Real. Accad. dei Lincei, Roma, 1883. See also Alfred Simpson, Travels in the Wilds of Ecuador, p. 91, sq. (London, 1886).

436

Ed. André, in Le Tour du Monde, 1883, p. 406.

437

Prof. Raimondi, in the Anthropological Review, Vol. I., p. 33, sq.

438

“La comunauté d’origine entre les Jivaros et les tribus du grand groupe guaranien se trouvera etablie avec assurance.” Dr. Hamy, “Nouveaux Renseignements sur les Indiens Jivaros,” in the Revue d’Anthropologie, 1873, p. 390.

439

The Mithridates (Bd. III., Ab. II., s. 592) gives from Hervas the Pater Noster in the Maina dialect. Professor Teza (Saggi inediti di Lingue Americane, pp. 54-57) has published the Pater Noster, Ave, Credo and Salve in the Cahuapana dialect. They differ but little.

440

See E. Pöppig, “Die Indiervölker des obern Huallaga,” in his Reise in Chile und Peru, Bd. II., ss. 320, 321, 400, etc.

441

Literature of American Aboriginal Languages, p. 12.

442

Olivier Ordinaire, “Les Sauvages du Perou,” in the Revue d’Ethnologie, 1887, p. 320.

443

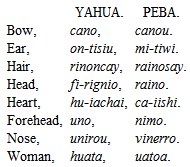

For example:

The Yahua has more Kechua elements than the Peba.

444

Lettres Edifiantes et Curieuses, Tome II., p. 112.

445

Von Martius, Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerikas, Bd. I., s. 445.

446

Reise in Chile und Peru, Bd. II., s. 415.

447

Jose Amich, Compendio Historico de la Serafica Religion, etc., pp. 77, 78.

448

E. Pöppig, Reise in Chile und Peru, Bd. II., s. 328 (Leipzig, 1836).

449

Cf. Olivier Ordinaire, “Les Sauvages du Perou,” in Revue d’Ethnologie, 1887, pp. 316, 317.

450

Von Martius, Ethnog. und Sprach. Amerikas, Bd. I., s. 435.

451

Compte-Rendu du Cong. Internat. des Américanistes, 1888, p. 438.

452

See Dr. L. F. Galt, “The Indians of Peru,” in Report of the Smithsonian Institution, 1877, p. 308, sq.

453

Professor Antonio Raimondi, Apuntes sobre la Provincia de Loreto (Lima, 1862), trans. by Bollaert, in Jour. Anthrop. Institute. He states that they speak a dialect of Pano.

454

D’Orbigny, L’Homme Américain, Tome II., p. 262.

455

W. Chandless, in Jour. of the Royal Geog. Soc., Vol. XXXIX., p. 302; Vol. XXXVI., p. 118.

456

Ibid., Vol. XXXVI., p. 123, note.

457

The Callisecas are now no longer known by that name; but J. Amich has given sufficient reasons to identify them as the ancestors of the tribe later known as the Setibos. See his Compendio Historico de la Serafica Religion en las Montañas de los Andes, p. 29 (Paris, 1854). Lieutenant Herndon, however, who describes them as wearing beards, believed they were the ancient Cashibos (Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon, p. 209. Washington, 1853).

458

According to Veigl. See Mithridates, III., II. 580, 581, 583.

459

Called also Mananaguas, “mountaineers,” and believed by Waitz to have been the Manoas among whom an old missionary found an elder of the tribe rehearsing the annals of the nation from a hieroglyphic scroll (Anthropologie der Naturvölker, Bd. III., s. 541). The real Manoas or Manaos belong to the Arawak stock.

460

W. Chandless, in Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, Vol. XXXVI., p. 118; Vol. XXXIX., p. 311.

461

Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde, Bd. I., s. 414.

462

Von Martius, Ibid., p. 422.

463

Scottish Geographical Magazine, 1890, p. 242.

464

Proceedings of the Royal Geog. Society, 1889, p. 501.

465

Muratori, Il Cristianesimo Felice, p. 27 (Venezia, 1743). Father Fernandez gives the names of 69 bands of the Manacicas (Lettres Edifiantes et Curieuses, Tom. II., p. 174).

466

A grammar of it has been edited by MM. Adam and Henry, Arte de la lengua Chiquita, Paris, 1880. (Bibliothèque Linguistique Américaine, Tom. VI.) The sub-divisions of the Chiquitos are so numerous that I refrain from encumbering my pages with them. See D’Orbigny, L’Homme Américain, Tom. II., p. 154, and authorities there quoted.

467

Hervas, Catalogo de las Lenguas Conocidas, Tom. I., p. 159.

468

Alcide D’Orbigny, L’Homme Américain, Vol. I., p. 356, sq. Among the D’Orbigny MSS. in the Bibliothèque Nationale, I found an inedited grammar and dictionary of the Yurucari language. It would be very desirable to have this published, as our present knowledge of the tongue rests on a few imperfect vocabularies. The work is doubtless that by P. la Cueva, mentioned in H. Ludewig, Lit. of Amer. Aborig. Languages, p. 206; but the author and editor of that work were in error in classing the Tacana and Maropa as members of the Yurucari stock. They belong to a different family.

469

L’Homme Américain, Tom. I., p. 374.

470

Scottish Geographical Magazine, 1890.

471

E. Heath, Kansas City Review, April, 1883. He gives vocabularies of Tacana and Maropa. A devotional work has been printed in Tacana.

472

Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, 1889, p. 498.

473

De Laet, quoted in Mithridates, Th. III., Ab. II., s. 577.

474

“En Aten se habla la Leca por ser este pueblo de Indios Lecos.” Descripcion de las Misiones de Apolobamba (Lima, 1771).

475

Weddell, Voyage dans la Bolivie, p. 453 (quoted by Waitz).