полная версия

полная версияThe American Race

218

Catalogo de las Lenguas conocidas. Madrid, 1805. This is the enlarged Spanish edition of the Italian original published in 1784, and it is the edition I have uniformity referred to in this work.

219

Personal Narrative, Vol. VI., p. 352 (English trans., London, 1826).

220

The Philosophic Grammar of American Languages, as set forth by Wilhelm von Humboldt; with the Translation of an Unpublished Memoir by him on the American Verb. By Daniel G. Brinton. (8vo. Philadelphia, 1885.) This Memoir was not included in the editions of Wilhelm von Humboldt’s Works, and was unknown even to their latest editor, Professor Steinthal. The original is in the Berlin Public Library.

221

L’Homme Américain de l’Amérique Méridionale, considéré sous ses Rapports Physiologiques et Moraux. Par Alcide D’Orbigny. 2 vols. Paris, 1839.

222

Organismus der Khetsua Sprache. Einleitung. (Leipzig, 1884.)

223

Beiträge zur Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerikas, zumal Brasiliens. Von Dr. Carl Friedrich Phil. von Martius. Leipzig, 1867. 2 vols.

224

Von Tschudi, Organismus der Kechua Sprache, s. 15, note.

225

He was superior general of the missions on the Marañon and its branches about 1730. See Lettres Edifiantes et Curieuses, Tom. II., p. 111, for his own description of his experiences and studies.

226

See especially his paper “Trois familles linguistiques des bassins de l’Amazone et de l’Orénoque,” in the Compte-Rendu du Congrès internationale des Américanistes, 1888, p. 489 sqq.

227

Joaquin Acosta, Compendio Historico de la Nueva Granada, p. 168. (Paris, 1848.)

228

Hist. de las Indias Occidentales, Dec. VII., Cap. XVI.

229

Dr. Max Uhle gives a list of 26 Cuna words, with analogies in the Chibcha and its dialects. (Compte-Rendu du Cong. Internat. Américanistes, 1888, p. 485.) Alphonse Pinart, who has published the best material on Cuna, is inclined to regard it as affiliated to the Carib. (Vocabulario Castellano-Cuna. Panama, 1882, and Paris, 1890.)

230

A. L. Pinart, Coleccion de Linguistica y Etnografia Americana, Tom. IV., p. 17; also the same writer in Revu d’Ethnographie, 1887, p. 117, and Vocabulario Castellano-Dorasque. Paris, 1890.

231

On the Chocos consult Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1876, s. 359; Felipe Perez, Jeografia del Estado del Cauca, p. 229, sq. (Bogota, 1862.) The vocabulary of Chami, collected near Marmato by C. Greiffenstein, and published in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1878, p. 135, is Choco. The vocabulary of the Tucuras, given by Dr. Ernst in the Verhandlungen der Berliner Anthrop. Gesell., 1887, p. 302, is quite pure Choco. The Chocos call their language embera bede, “the speech of men.”

232

“Relacion de las tierras y provincias de la gobernacion de Venezuela (1546),” in Oviedo y Baños, Historia de Venezuela, Tom. II. Appendice. (Ed. Madrid, 1885.)

233

Aristides Rojas, Estudios Indigenos, p. 46. (Caracas, 1878.)

234

“Mas hermosas y agraciadas que las de otros de aquel continente.” This was the opinion of Alonzo de Ojeda, who saw them in 1499 and later. (Navarrete, Viages, Tom. III., p. 9). Their lacustrine villages reminded him so much of Venice (Venezia) that he named the country “Venezuela.”

235

According to Lares, the Bobures and Motilones lived adjacent, and to the north of the Timotes. The Motilones were of the Carib stock. See Dr. A. Ernst, in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1885, p. 190.

236

Joaquin Acosta, Compend. Hist. de la Nueva Granada, p. 31, note.

237

Martin Fernandez de Enciso, La Suma de Geografia. (Sevilla, 1519.) This rare work is quoted by J. Acosta. Enciso was alguacil mayor of Castilla de Oro in 1515.

238

See Jose Ignacio Lares, Resumen de las Actas de la Academia Venezolana, 1886, p. 37 (Caracas, 1886); and Dr. Ernst, in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1885, s. 190.

239

G. Coleti, Dizionario dell’ America Meridionale, s. v. (Venezia, 1771.) Not to be confounded with the Zaparos of the Marañon.

240

Ibid., s. v.

241

G. Marcano, Ethnographie Pre-Columbienne de Venezuela. (Paris, 1889.)

242

“La lingua Muysca, detta anticamente Chybcha, era la comune e generale in tuttigl’ Indiani di quella Monarchia.” Coleti, Dizionario Storico-Geografico dell’ America Meridionale, Tom. II., p. 39. (Venezia, 1771.)

243

“Casi todos los pueblos del Nuevo Reyno de Granada son de Indios Mozcas.” Alcedo, Diccionario Geografico de America, s. v. Moscas. “La lengua Mosca es como general en estendissima parte de aquel territorio; en cada nacion la hablan de distinta manera.” J. Cassani, Historia del Nuevo Reyno de Granada, p. 48. (Madrid, 1741.) He especially names the Chitas, Guacicas, Morcotes and Tunebos as speaking Chibcha.

244

Herrera, Historia de las Indias Occidentales, Dec. IV., Lib. X., cap. 8.

245

Rafael Celedon, Gramatica de la Lengua Köggaba, Introd., p. xxiv. (Bibliothèque Linguistique Américaine.)

246

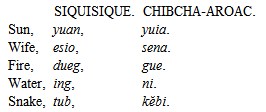

The vocabulary is furnished by General Juan Thomas Perez, in the Resumen de las Actas de la Academia Venezolana, 1886, p. 54. I offer for comparison the following:

247

The connection of the Aroac (not Arawak) dialects with the Chibcha was, I believe, first pointed out by Friedrich Müller, in his Grundriss der Sprachwissenschaft, Bd. IV., s. 189, note. The fact was also noted independently by Dr. Max Uhle, who added the Guaymis and Talamancas to the family. (Compte Rendu du Congrès Internat. des Américanistes, 1888, p. 466.)

248

Pinart, Bulletin de la Société de Geographie, 1885; Berendt, in Bull. of Amer. Geog. Society, 1876, No. 2.

249

In Sixth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology. Washington, 1888.

250

Joaquin Acosta, Compendio Historico de la Nueva Granada, p. 77. When, in 1606, the missionary Melchor Hernandez visited Chiriqui lagoon, he found six distinct languages spoken on and near its shores by tribes whom he names as follows: Cothos, Borisques, Dorasques, Utelaes, Bugabaes, Zunes, Dolegas, Chagres, Zaribas, Dures. (Id., p. 454.)

251

The only information I have on the Paniquita dialect is that given in the Revue de Linguistique, July, 1879, by a missionary (name not furnished). It consists of a short vocabulary and some grammatical remarks.

252

Herrera, Descripcion de las Indias Occidentales, Cap. XVI.

253

Alcedo, Diccionario Geografico, s. v., Muzos.

254

Vocabulario Paez-Castellano, por Eujenio del Castillo i Orosco. Con adiciones por Ezequiel Uricoechea. Paris, 1877. (Bibliothèque Linguistique Américaine.)

255

Felipe Perez, Geografia del Estado de Tolima, p. 76 (Bogota, 1863); R. B. White, in Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 1883, pp. 250-2.

256

Dr. A. Posada-Arango, “Essai Ethnographique sur les Aborigenes de l’Etat d’Antioquia,” in the Bulletin de la Société Anthrop. de Paris, 1871, p. 202.

257

Thirty thousand, says Herrera, with the usual extravagance of the early writers (Decadas de Indias, Dec. VII., Lib. IV., cap IV.)

258

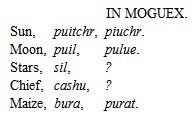

Leon Douay, in Compte Rendu du Congrès des Américanistes, 1888, p. 774, who adds a vocabulary of Moguex. The name is derived from Mog, vir.

259

Hervas, Catologo de las Lenguas Conocidas, Tom. I., p. 279. Father Juan de Ribera translated the Catechism into the Guanuca, but so far as I know, it was not printed.

260

Bollaert, Antiquarian and Ethnological Researches, etc., pp. 6, 64, etc. The words he gives in Coconuca are:

Bollaert probably quoted these without acknowledgment from Gen. Mosquera, Phys. & Polit. Geog. of New Granada, p. 45 (New York, 1853).

261

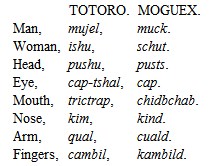

My knowledge of the Totoro is obtained from an anonymous notice published by a missionary in the Revue de Linguistique, July, 1879. Its relationship to the group is at once seen by the following comparison:

262

See Herrera, Hist. de las Indias, Dec. VI., Lib. VII., cap. V.

263

The vocabulary was furnished by Bishop Thiel. It is edited with useful comments by Dr. Edward Seler in Original-Mittheilungen aus der Ethnologischen Abtheilung der König. Museen zu Berlin, No. I., s. 44, sq. (Berlin, 1885).

264

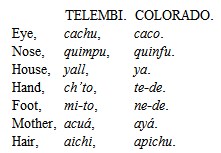

Ed. André, in Le Tour du Monde, 1883, p. 344. From this very meagre material I offer the following comparison:

The terminal syllable to in the Telembi words for hand and foot appears to be the Colorado té, branch, which is also found in the Col. té-michu, finger, te-chili, arm ornament, and again in the Telembi t’raill, arm.

265

In the Verhandlungen der Berliner Anthrop. Gesellschaft, 1887, ss. 597-99.

266

Other analogies are undoubted, though less obvious. Thus in Cayapa, “man” is liu-pula; “woman,” su-pula. In these words, the terminal pula is generic, and the prefixes are the Colorado sona, woman, abbreviated to so in the Colorado itself, (see Dr. Seler’s article, p. 55); and the Col. chilla, male, which in the Spanish-American pronunciation, where ll = y, is close to liu.

267

Bollaert, Antiquarian and Ethnological Researches, p. 82.

268

Manuel I. Albis, in Bulletin of the Amer. Ethnol. Soc., vol. I., p. 52.

269

A. Codazzi in Felipe Perez, Jeografia del Estado de Tolima, pp. 81 sqq. (Bogota, 1863.)

270

As tooth, Andaqui, sicoga; Chibcha, sica.house, ” co-joe; ” jüe.271

Manuel P. Albis, in Bull. of the Amer. Ethnolog. Soc., Vol. I., pp. 55, sq. See also General T. C. de Mosquera, Memoir on the Physical and Political Geography of New Granada, p. 41 (New York, 1853).

272

Garcilasso de la Vega, Commentarios Reales, Lib. VIII., cap. 5. He calls the natives Huancavillcas.

273

F. G. Saurez, Estudio Historico sobre los Cañaris (Quito, 1878). This author gives cuts of these axes, and their inscribed devices.

274

For a description, with cuts, see M. L. Heuzey, “Le Trésor de Cuenca,” in La Gazette des Beaux-Arts, August, 1870.

275

Cronica del Peru, Pt. I., cap. cxvi.

276

Comentarios Reales de los Incas, Lib. VII., cap. 3.

277

Antiquarian, Ethnological and other Researches, in New Granada, Ecuador, Peru and Chili, p. 101 (London, 1860).

278

He complains that the languages which the Incas tried to suppress, had, since their downfall, arisen as vigorous as ever, Comentarios Reales de los Incas, Lib. VII., cap. 3.

279

Organismus der Khetsua Sprache, s. 64 (Leipzig, 1884).

280

See von Tschudi, Organismus der Khetsua Sprache, s. 65. It is to be regretted that in the face of the conclusive proof to the contrary, Dr. Middendorf repeats as correct the statement of Garcilasso de la Vega (Ollanta, Einleitung, s. 15, note).

281

See his Introduction to the Travels of Pedro Cieza de Leon, p. xxii. (London, 1864).

282

See his Organismus der Khetsua Sprache, ss. 64-66.

283

The Chinchaya dialect is preserved (insufficiently) by Father Juan de Figueredo in an Appendix to Torres-Rubio, Arte de la Lengua Quichua, edition of Lima, 1701. It retained the sounds of g and l, not known in southern Kechua. The differences in the vocabularies of the two are apparent rather than real. Thus the Chin. rupay, sun, is the K. for sun’s heat (ardor del sol); Chin. caclla, face, is K. cacclla, cheeks. Markham is decidedly in error in saying that the Chinchaya dialect “differed very considerably from that of the Incas” (Journal Royal Geog. Soc., 1871, p. 316).

284

Introduction to his translation of Cieza de Leon, p. xlvii, note.

285

Bollaert, Antiquarian and Ethnological Researches, p. 81.

286

Von Tschudi, Organismus der Khetsua Sprache, s. 66. Hervas was also of the opinion that both Quitu and Scyra were Kechua dialects (Catalogo de las Lenguas Conocidas, Tom. I., p. 276).

287

A. Bastian, Die Culturländer des Alten Americas, Bd. II., s. 93.

288

Juan de Velasco, Histoire du Royaume de Quito, pp. 11-21, sq. (Ed. Ternaux-Compans, Paris, 1840.) But Cieza de Leon’s expressions imply the existence of the matriarchal system among them. See Markham’s translation, p. 83, note. Some claim that the Quitus were a different, and, in their locality, a more ancient tribe than the Caras.

289

Relaciones Geograficas de Indias. Peru. Tom. I., p. 19. (Madrid, 1881.)

290

In Le Tour du Monde, 1883, p. 406. The word Yumbo appears to be derived from the Paez yombo, river, and was applied to the down-stream Indians.

291

“Casi tal come lo enseñaron los conquistadores.” Manuel Villavicencio, Geografia de la Republica del Ecuador, pp. 168, 354, 413, etc. (New York, 1858.) According to Dr. Middendorf, the limit of the Incarial power (which, however, is not identical in this region with that of the Kechua tongue), was the Blue river, the Rio Ancasmayu, an affluent of the upper Patia. (Ollanta, Einleitung, s. 5. Berlin, 1890.)

292

Mr. C. Buckley, “Notes on the Macas Indians of Ecuador,” in Journal of the Anthropological Institute, 1874, pp. 29, sqq.

293

References in Waitz, Anthropologie der Naturvölker, Bd. III., s. 492.

294

Arte de la Lengua Chilena, Introd. (Lima, 1606).

295

Paul Topinard, in Revue d’Anthropologie, Tome IV., pp. 65-67.

296

Lucien Carr, Fourth Report of the Peabody Museum of Archæology.

297

I would especially refer to the admirable analysis of the Peruvian governmental system by Dr. Gustav Brühl, Die Culturvölker Alt-Amerikas, p. 335, sqq. (Cincinnati, 1887.) I regret that the learned Kechuist, Dr. E. W. Middendorf, had not studied this book before he prepared his edition of the Ollanta drama (Berlin, 1890), or he would have modified many of the statements in its Einleitung.

298

See J. J. von Tschudi, “Das Lama,” in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1885, s. 93.

299

Dr. Nehring has shown that all the breeds of Peruvian dogs can be traced back to what is known as the Inca shepherd dog. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1885, s. 520.

300

Grundriss der Sprachwissenschaft, Bd. II., Abth. I., 370.

301

A careful edition is that of G. Pacheco Zegarra, Ollantai; Drame en Vers Quechuas du temps des Incas (Paris, 1878); an English translation, quite faulty, was given by C. G. Markham (London, 1871); one in Kechua and German by Von Tschudi, and recently (1890) Dr. Middendorf’s edition claims greater accuracy than its predecessors.

302

Espada, Yaravies Quiteños. (Madrid, 1881.)

303

J. J. Von Tschudi, Organismus der Khetsua Sprache (Leipzig, 1884); Dr. E. W. Middendorf, Das Runa Simi, oder die Keshua Sprache. (Leipzig, 1890.)

304

The Yauyos spoke the Cauqui dialect, which was somewhat akin to Aymara.

305

See Markham’s paper in Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 1871, p. 309.

306

Arte de la Lengua Aymara, Roma, 1603; Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara, Juli, 1612. Both have been republished by Julius Platzmann, Leipzig, 1879.

307

See Steinthal, “Das Verhältniss zwischen dem Ketschua und Aimara,” in Compte-Rendu du Congrès International des Américanistes, 1888, p. 462. David Forbes reverses the ordinary view, and considers the Kechua language and culture as mixed and late products derived from an older Aymara civilization. See his article on the Aymara Indians in Journal of the Ethnological Society of London, 1870, p. 270, sqq.

308

“Principalmente se enseña en este Arte la lengua Lupaca, la qual no es inferior a la Pacasa, que entre todas las lenguas Aymaricas tiene el primer lugar.” Bertonio, Arte de la Lengua Aymara, p. 10.

309

For measurements, etc., see David Forbes, in Journal of the London Ethnological Society, October, 1870.

310

One of the most satisfactory descriptions of them is by E. G. Squier, Travels in Peru, Chaps. XV., XVI. (New York, 1877).

311

The observations of David Forbes on the present architecture of the Aymaras lend strong support to his theory that the structures of Tiahuanuco, if not projected by that nation, were carried out by Aymara architects and workmen. See his remarks in Jour. of the London Ethnol. Soc., 1870, p. 259.

312

D’Orbigny, L’Homme Américain, Tome I., p. 309.

313

Quoted by A. Bastian.

314

“Son estos Uros tan brutales que ellos mismos no se tienen por hombres.” Acosta, Historia de las Indias, p. 62 (Ed. 1591).

315

“Los Indios Puquinas … son rudos y torpes.” La Vega, Comentarios Reales de los Incas, Lib. VII., cap. 4.

316

Mithridates, Theil III., Abth. II., ss. 548-550.

317

In the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 1871, p. 305.

318

In his Organismus der Ketschua Sprache, s. 76 (Leipzig, 1884).

319

Relaciones Geograficas de Indias. Peru, Tom. I., p. 82. (Madrid, 1881.)

320

Fernando de la Carrera, Arte de la Lengua Yunga. (Lima, 1644, reprint, Lima, 1880.)

321

See Von Tschudi, Die Kechua Sprache, p. 83, 84.

322

Charles Wiener, Perou et Bolivie, p. 98, seq. (Paris, 1880.)

323

Commentarios Reales, Lib. VI., cap. 32.

324

See the chapter on “The Art, Customs and Religion of the Chimus,” in E. G. Squier’s Peru, p. 170, sq. (New York, 1877.)

325

“En la lengua Mochica de los Yungas.” Geronimo de Ore, Rituale seu Manuale Peruanum. (Neapoli, 1607.)

326

A. Bastian, Die Culturländer Alt-Amer. Bd. II.

327

In C. R. Markham’s translation of Cieza de Leon, Introduction, p. xlii. (London, 1864.)

328

Catalogo de las Lenguas Conocidas, Tome I., p. 274.

329

Dr. R. A. Philippi, Reise durch die Wüste Atacama, s. 66. (Halle, 1860.) J. J. von Tschudi, Reisen durch Sud-Amerika, Bd. V., s. 82-84. T. H. Moore, Compte-Rendu du Congrès Internat. des Américanistes, 1877, Vol. II., p. 44, sq. Francisco J. San-Roman, La Lengua Cunza de los Naturales de Atacama (Santiago de Chile, 1890). The word cunza in this tongue is the pronoun “our,”—the natives speak of lengua cunza, “our language.” Tschudi gives the only text I know—two versions of the Lord’s Prayer.

330

“Con la nacion Aymara esta visiblimente emparentada la Atacameña.” Dr. L. Darapsky, “Estudios Linguisticos Americanos,” in the Bulletin del Instituto Geog. Argentino, 1890, p. 96.

331

L’Homme Américain, Tom. II., p. 330.

332

Organismus der Khetsua Sprache, s. 71, and Reisen, Bd. V., s. 84.

333

Alcide D’Orbigny, L’Homme Américain, Tome I., p. 334. (Paris, 1839.)

334

“Entre los Changos no se conserva vestigio de lengua indijena alguna.” F. J. San-Roman, La Lengua Cunza, p. 4.

335

Wallace estimates the area of the Amazon basin alone, not including that of the Rio Tocantins, which he regards as a different system, at 2,300,000 square miles. (Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro, p. 526.)

336

See authorities in Von Martius, Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerikas, Bd. I., s. 185. (Leipzig, 1867.)

337

The origin of the Chiriguanos is related from authentic traditions by Nicolas del Techo, Historia Provinciæ Paraquariæ, Lib. XI., Cap. 2. The name Chiriguano means “cold,” from the temperature of the upland region to which they removed.