полная версия

полная версияThe American Race

86

Dr. Washington Matthews, in Journal of American Folk-Lore, 1890, p. 90.

87

The student of this language finds excellent material in the Dictionnaire de la Langue Déné-Dindjié, par E. Petitot (folio, Paris, 1876), in which three dialects are presented.

88

Stephen Powers, Tribes of California, p. 72, 76 (Washington, 1877).

89

“On voit que leur conformation est à peu près exactement le nôtre.” Quetelet, “Sur les Indiens O-jib-be-was,” in Bull. Acad. Royale de Belgique, Tome XIII.

90

I refer to the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia. The numerous measurements of skulls of New England Algonkins by Lucien Carr, show them to be mesocephalic tending to dolichocephaly, orthognathic, mesorhine and megaseme. See his article, “Notes on the Crania of New England Indians,” in the Anniversary Memoirs of the Boston Society of Natural History, 1880.

91

The best work on this subject is Dr. C. C. Abbott’s Primitive Industry (Salem, 1881).

92

The Lenâpé and their Legends; with the Complete Text and Symbols of the Walum Olum, and an Inquiry into its Authenticity. By Daniel G. Brinton, Philadelphia, 1885 (Vol. V. of Brinton’s Library of Aboriginal American Literature).

93

See Horatio Hale, “Report on the Blackfeet,” in Proc. of the Brit. Assoc. for the Adv. of Science, 1885.

94

See Lenâpé-English Dictionary: From an anonymous MS. in the Archives of the Moravian Church at Bethlehem, Pa. Edited with additions by Daniel G. Brinton, M. D., and Rev. Albert Seqaqkind Anthony. Published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, 1888. Quarto, pp. 236.

95

J. Aitken Meigs, “Cranial Forms of the American Aborigines,” in Proceedings of the Acad. of Nat. Sciences of Philadelphia, May, 1866.

96

Horatio Hale, The Iroquois Book of Rites, pp. 21, 22. (Philadelphia, 1883. Vol. II. of Brinton’s Library of Aboriginal American Literature.)

97

J. W. Powell, First Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, p. 61. (Washington, 1881.)

98

The Iroquois Book of Rites, referred to above.

99

There are twenty-one skulls alleged to be of Muskoki origin in the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, of which fifteen have a cephalic index below 80.

100

Examples given by William Bartram in his MSS. in the Pennsylvania Historical Society.

101

See on this subject an essay on “The Probable Nationality of the Mound-Builders,” in my Essays of an Americanist, p. 67. (Philadelphia, 1890.)

102

D. G. Brinton, “The National legend of the Chahta-Muskoki Tribes,” in The Historical Magazine, February, 1870. (Republished in Vol. IV. of Brinton’s Library of Aboriginal American Literature.)

103

“The Seminole Indians of Florida,” by Clay MacCauley, in Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1883-4.

104

See for the Yuchis, their myths and language, Gatschet in Science, 1885, p. 253.

105

Arte de la Lengua Timuquana compuesto en 1614 per el Pe Francisco Pereja. Reprint by Lucien Adam and Julien Vinson, Paris, 1886. An analytical study of the language has been published by Raoul de la Grasserie in the Compte Rendu du Congrès International des Américanistes, 1888.

106

See “The Curious Hoax of the Taensa Language” in my Essays of an Americanist, p. 452.

107

D. G. Brinton, “The Language of the Natchez,” in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 1873.

108

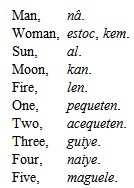

Die Länder am untern Rio Bravo del Norte. S. 120, sqq. (Heidelberg, 1861.) I give the following words from his vocabulary of the Carrizos:

The numbers three, four and five are plainly the Nahuatl yey, nahui, macuilli, borrowed from their Uto-Aztecan neighbors.

109

Bartolomé Garcia, Manuel para administrar los Santos Sacramentos. (Mexico, 1760.) It was written especially for the tribes about the mission of San Antonio in Texas.

110

As chiquat, woman, Nah. cihuatl; baah-ka, to drink, Nah. paitia. The song is given, with several obvious errors, in Pimentel, Lenguas Indigenas de Mexico, Tom. III., p. 564; Orozco y Berra’s lists mentions only the Aratines, Geografia de las Lenguas de Mexico, p. 295.

111

Adolph Uhde, Die Länder am unteru Rio Bravo del Norte, p. 120.

112

The name Pani is not a word of contempt from the Algonkin language, as has often been stated, but is from the tongue of the people itself. Pariki means a horn, in the Arikari dialect uriki, and refers to their peculiar scalp-lock, dressed to stand erect and curve slightly backward, like a horn. From these two words came the English forms Pawnee and Arikaree. (Dunbar.)

113

The authorities on the Panis are John B. Dunbar, in the Magazine of American History, 1888; Hayden, Indian Tribes of the Missouri Valley (Philadelphia, 1862), and various government reports.

114

J. Owen Dorsey, “Migrations of Siouan Tribes,” in the American Naturalist, 1886, p. 111. The numerous and profound studies of this stock by Mr. Dorsey must form the basis of all future investigation of its history and sociology.

115

The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia.

116

Mrs. Mary Eastman, Dahcotah; or Life and Legends of the Sioux, p. 211. (New York, 1849.)

117

W. P. Clark, Indian Sign Language, p. 229 (Philadelphia, 1885); Whipple, Ewbank and Turner, Report on Indian Tribes, pp. 28, 80. (Washington, 1855.)

118

R. Virchow, Verhand. der Berliner Gesell. für Anthropologie, 1889, s. 400.

119

Dr. Franz Boas, “Fourth Report on the Tribes of the North West Coast,” in Proceed. Brit. Assoc. Adv. Science, 1887.

120

Dr. J. L. Le Conte, “On the Distinctive Characteristics of the Indians of California,” in Trans. of the Amer. Assoc. for the Adv. of Science, 1852, p. 379.

121

Dr. Aurel Krause, Die Tlinkit Indianer. (Jena, 1885.)

122

See the various reports of Dr. Boas to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and the papers of Messrs. Tolmie and Dawson, published by the Canadian government.

123

A Manual of the Oregon Trade Language or Chinook Jargon. By Horatio Hale. (London, 1890.)

124

Dr. W. F. Corbusier, in American Antiquarian, 1886, p. 276; Dr. Ten Kate, in Verhand. der Berliner Gesell. Für Anthrop., 1889, s. 667.

125

J. R. Bartlett, Explorations in New Mexico, Vol. I., p. 464. C. A. Pajeken, Reise-Erinnerungen in ethnographischen Bildern, s. 97.

126

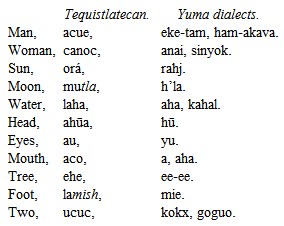

Whipple, Ewbank and Turner, Report on Indian Tribes (Washington, 1855), and numerous later authorities, give full information about the Yumas.

127

Jacob Baegert, Nachricht von den Amerikanischen Halbinsel Californien. (Mannheim, 1773.)

128

I have not included in the stock the so-called M’Mat stem, introduced erroneously by Mr. Gatschet, as Dr. Ten Kate has shown no such branch exists. See Verhandlungen der Berliner Anthrop. Gesell., 1889, ss. 666-7.

129

Mr. E. A. Barber estimates that the area in which the characteristic remains of the cliff-dwellers and pueblos are found contains 200,000 square miles. Compte Rendu du Congrès des Américanistes, 1878, Tome I., p. 25.

130

“Casas y atalayas eregidas dentro de las peñas.” I owe the quotation to Alphonse Pinart.

131

The Tze-tinne; Capt. J. G. Bourke, in Jour. Amer. Folk-lore, 1890, p. 114.

132

This affinity was first demonstrated by Buschmann in his Spuren der aztekischen Sprache, though Mr. Bandelier erroneously attributes it to later authority. See his very useful Report of Investigations among the Indians of the South Western United States, p. 116. (Cambridge, 1890.) Readers will find in these excellent reports abundant materials on the Pueblo Indians and their neighbors.

133

Buschmann, Die Spuren der aztekischen Sprache im nördlichen Mexiko und höheren Americanischen Norden. 4to. Berlin, 1859, pp. 819.

Grammatik der Sonorischen Sprachen. 4to. Berlin, Pt. I., 1864, pp. 266; Pt. II., 1867, pp. 215.

134

Perez de Ribas, Historia de los Triomphos de Nuestra Santa Fé, Lib. I., cap. 19.

135

Anales del Ministerio de Fomento, p. 99. (Mexico, 1881.)

136

Col. A. G. Brackett, in Rep. of the Smithson. Inst. 1879, p. 329.

137

Capt. W. P. Clark, The Indian Sign Language, p. 118. (Philadelphia, 1885.)

138

Ibid., p. 338.

139

See Contributions to North American Ethnology, Vol. I., p. 224. (Washington, 1877).

140

R. Virchow, Crania Ethnica Americana.

141

W. P. Clark, The Indian Sign Language, p. 118.

142

The Snake Dance of the Moquis of Arizona. By John G. Bourke. (New York, 1884.)

143

For these legends see Captain F. E. Grossman, U. S. A., in Report of the Smithsonian Institution, pp. 407-10. They attribute the Casas Grandes to Sivano, a famous warrior, the direct descendant of Söhö, the hero of their flood myth.

144

The Apaches called them Tze-tinne, Stone House People. See Capt. John G. Bourke, Journal of American Folk-Lore, 1890, p. 114. The Apaches Tontos were the first to wander down the Little Colorado river.

145

See the descriptions of the Nevomes (Pimas) in Perez de Ribas, Historia de los Triumphos de Nuestra Santa Fé, Lib. VI., cap. 2. (Madrid, 1645.)

146

“Las casas eran o de madera, y palos de monte, o de piedra y barro; y sus poblaciones unas rancherias, a modo de casilas.” Ribas, Historia de los Triumphos de Nuestra Santa Fé, Lib. X., cap. 1. (Madrid, 1645.)

147

Torquemada, Monarquia Indiana, Lib. V., cap. 44. An interesting sketch of the recent condition of these tribes is given by C. A. Pajeken, Reise-Erinnerungen, pp. 91-98. (Bremen, 1861.)

148

Perez de Ribas, Historia, etc., Lib. II., cap. 33.

149

Eustaquio Buelna, Peregrinacion de los Aztecas y Nombres Geograficos Indigenas de Sinaloa, p. 20. (Mexico, 1887.)

150

Buelna, loc. cit., p. 21.

151

Father Perez de Ribas, who collected these traditions with care, reports this fact. Historia de los Triumphos, etc., Lib. I., cap. 19.

152

See “The Toltecs and their Fabulous Empire,” in my Essays of an Americanist, pp. 83-100.

153

There is an interesting anonymous MS. in the Fond Espagnol of the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris, with the title La Guerra de los Chichimecas. The writer explains the name as a generic term applied to any tribe without settled abode, “vagos, sin casa ni sementera.” He instances the Pamis, the Guachichiles and the Guamaumas as Chichimeca, though speaking quite different languages.

154

“Cuitlatl, = mierda” (Molina, Vocabulario Mexicano). Cuitlatlan, Ort des Kothes (Buschmann, Aztekische Ortsnamen, s. 621), applied to the region between Michoacan and the Pacific; also to a locality near Techan in the province of Guerrero (Orozco y Berra, Geog. de las Lenguas, p. 233).

155

Dr. Gustav Brühl believes these schools were limited to those designed for warriors or the priesthood. Sahagun certainly assigns them a wider scope. See Brühl, Die Calturvölker Alt-Amerikas, pp. 337-8.

156

See “The Ikonomatic Method of Phonetic Writing” in my Essays of an Americanist, p. 213. (Philadelphia, 1890.)

157

Four skulls in the collection of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, give a cephalic index of 73.

158

Sahagun, Historia de la Nueva España, Lib. X, cap. 29.

159

D. G. Brinton, Ancient Nahuatl Poetry, p. 134. (Philadelphia, 1887, in Library of Aboriginal American Literature.)

160

E. G. Tarayre, Explorations des Regions Mexicaines, p. 282. (Paris, 1879).

161

D. G. Brinton, Essays of an Americanist, p. 366.

162

H. de Charencey, Melanges de Philologie et de Palæographie Américaine, p. 23.

163

Sahagun, Historia, Lib. X, cap. 29. The name is properly Tarex, applied later in the general sense of “deity,” “idol.” Tarex is identified by Sahagun with the Nahuatl divinity Mixcoatl, the god of the storm, especially the thunder storm. The other derivations of the name Tarascos seem trivial. See Dr. Nicolas Leon, in Anales del Museo Michoacano, Tom. I. Their ancestors were known as Taruchas, in which we see the same radical.

164

Dr. Nicolas Leon, of Morelia, Michoacan, whose studies of the archæology of his State have been most praiseworthy, places the beginning of the dynasty at 1200; Anales del Museo Michoacano, Tom. I., p. 116.

165

From the Nahuatl, yacatl, point, apex, nose; though other derivations have been suggested.

166

For numerous authorities, see Bancroft, Native Races of the Pacific Coast, vol. II., pp. 407-8; and on the antiquities of the country, Dr. Leon, in the Anales del Museo Michoacano, passim, and Beaumont, Cronica de la Provincia de Mechoacan, Tom. III., p. 87, sq. (Mexico, 1874).

167

Sahagun, Historia de la Nueva España, Lib. X., cap. 6.

168

Herrera, Historia de las Indias Occidentales, Dec. II., Lib. V., cap. 8.

169

Strebel, Alt-Mexiko.

170

Pimentel, Lenguas Indigenas de Mexico, Tom. III., p. 345, sq.

171

From didja, language, za, the national name.

172

Mr. A. Bandelier, in his careful description of these ruins (Report of an Archæological Tour in Mexico, Boston, 1884) spells this Lyo-ba. But an extensive MS. Vocabulario Zapoteco in my possession gives the orthography riyoo baa.

173

Garcia, Origen de los Indios, Lib. V., cap. IV., gives a lengthy extract from one of their hieroglyphic mythological books.

174

Sahagun, Historia de la Nueva España, Lib. X., cap. VI.

175

Herrera, Historia de las Indias Occidentales. Dec. IV., Lib. X., cap. 7.

176

Explorations and Surveys of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, pp. 126-7. (Washington, 1872.)

177

J. G. Barnard, The Isthmus of Tehuantepec, pp. 224, 225. (New York, 1853.)

178

Apuntes sobre la Lengua Chinanteca, MS.

179

Herrera, Hist. de las Indias Occidentales. Dec. III., Lib. III., cap. 15.

180

Herrera, Historia de las Indias Occidentales. Dec. IV., Lib. X., cap. 11.

181

Gregoria Garcia, Origen de los Indios, Lib. V., cap. v.

182

Oviedo, Historia General de las Indias, Lib. XLII., cap. 5.

183

Peralta, Costa Rica, Nicaragua y Panama, en el Siglo XVI, p. 777. (Madrid, 1883.)

184

Lucien Adam, La Langue Chiàpanéque (Vienna, 1887); Fr. Müller, Grundriss der Sprachwissenschaft, Bd. IV., Abt. I. s. 177.

185

Anales del Ministerio de Fomento, p. 98. (Mexico, 1881.)

186

Beristain y Souza, Biblioteca Hispano-Americana Septentrional, Tomo I., p. 438.

187

For example:

188

Geografia de las Lenguas de Mejico, p. 187.

189

Historia de las Indias Occidentales, Dec. III., Lib. VII., cap. III.

190

See also Dr. Berendt’s observations on this language in Lewis H. Morgan’s Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity in the Human Family, p. 263. (Washington, 1871.)

191

In his Nicaragua, its People, Scenery and Monuments, Vol. II., pp. 314, 324. (New York, 1856.)

192

“Fr. Francisco de las Naucas primus omnium Indos qui Popolocae nuncupantur anno Dom. 1540, divino lavacro tinxit, quorum duobus mensibus plus quam duodecim millia baptizati sunt.” Franciscus Gonzaga, De Origine Seraphicae Religionis, p. 1245. (Romae, 1587.)

193

“Fr. Francisco de Toral, obispo que fué de Yucatan, supo primero de otro alguno la lengua popoloca de Tecamachcalco, y en ella hizo arte y vocabulario, y otras obras doctrinales.” Geronimo de Mendieta, Historia Eclesiastica Indiana, Lib. V., cap. 44.

194

“Linguâ Mexicanâ paullulum diversa.” De Laet, Novus Orbis, p. 25.

195

Historia de las Indias Occidentales, Decad. II., Lib. X., cap. 21.

196

See the note of J. G. Icazbalceta to the Doctrina of Fernandez, in H. Harrisse’s Biblioteca Americana Vetustissima, p. 445, sq.

197

Geografia de las Lenguas de Mejico, p. 273.

198

See an article “Los Tecos,” in the Anales del Museo Michoacano, Año II., p. 26.

199

Domingo Juarros, Compendio de la Historia de la Ciudad de Guatemala, Tomo I., pp. 102, 104, et al. (Ed. Guatemala, 1857.)

200

Dr. Otto Stoll, Zur Ethnographie der Republik Guatemala, s. 26 (Zurich, 1884).

201

In the Sitzungsbericht der Kais. Akad. der Wissenschaften, Wien, 1855.

202

“Demas de ocho cientos años,” says Herrera. Historia de las Indias Occidentales, Dec. III., Lib. IV., Cap. XVIII.

203

I have edited some of these with translations and notes, in The Maya Chronicles, Philadelphia, 1882. (Volume I. of my Library of Aboriginal American Literature).

204

Sahagun, Historia de la Nueva España, Lib. X., cap. 29, sec. 12.

205

One of the most remarkable of these coincidences is that in the decoration of shells pointed out by Mr. Wm. H. Holmes, in his article on “Art in Shells,” in the Second Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology. (Washington, 1883.)

206

On this point see “The Lineal Measures of the Semi-Civilized Nations of Mexico and Central America,” in my Essays of an Americanist, p. 433. (Philadelphia, 1890.)

207

The principal authority is the work of Diego de Landa, Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan. It has been twice published, once imperfectly by the Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg, Paris, 1864, 8vo.; later very accurately by the Spanish government, Madrid, 1881, folio.

208

The most profitable studies in the Maya hieroglyphs have been by Dr. Cyrus Thomas in the United States, Dr. E. Förstemann, Ed. Seler and Schellhas in Germany, and Prof. L. de Rosny in France. On the MSS. or codices preserved, see “The Writings and Records of the Ancient Mayas” in my Essays of an Americanist, pp. 230-254.

209

Popul Vuh, Le Livre Sacré. Paris, 1861.

210

The Annals of the Cakchiquels, the original text with a Translation, Notes and Introduction. Phila., 1885. (Volume VI. of my Library of Aboriginal American Literature.)

211

See “The Books of Chilan Balam,” in my Essays of an Americanist, pp. 255-273.

212

The name Huaves is derived from the Zapotec huavi, to become rotten through dampness. (Vocabulario Zapoteco. MS. in my possession.) It was probably a term of contempt.

213

Nicaragua, its People and Scenery, Vol. II., p. 310.

214

E. G. Squier, “A Visit to the Guajiquero Indians,” in Harper’s Magazine, October, 1859. A copy of his vocabularies is in my possession.

215

I collected and published some years ago the only linguistic material known regarding this tribe. “On the Language and Ethnologic Position of the Xinca Indians of Guatemala,” in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 1884.

216

On the ethnography of the Musquito coast consult John Collinson, in Mems. of the Anthrop. Soc. of London, Vol. III., p. 149, sq.; C. N. Bell, in Jour. of the Royal Geograph. Soc., Vol. XXXII., p. 257, and the Bericht of the German Commission, Berlin, 1845. Lucien Adam has recently prepared a careful study of the Musquito language.

217

See Leon Fernandez and J. F. Bransford, in Rep. of the Smithsonian Institution, 1882, p. 675; B. A. Thiel, Apuntes Lexicograficos, Parte III.; O. J. Parker, in Beach’s Indian Miscellany, p. 346.